Source: Link

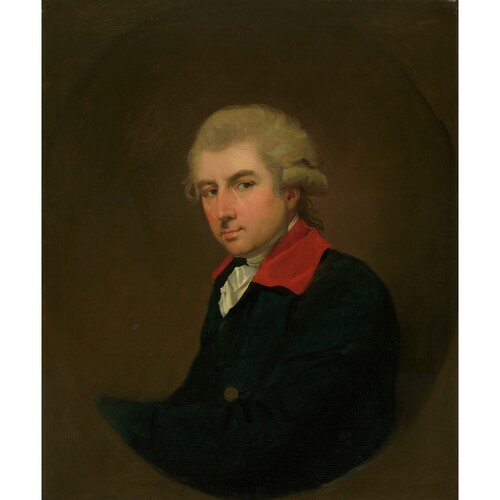

BURTON, Sir FRANCIS NATHANIEL, colonial administrator; b. 26 Dec. 1766 in London, younger twin son of Francis Pierpont Burton and Elizabeth Clements; m. 4 June 1801 Valentina Letitia Lawless, daughter of Nicholas Lawless, 1st Baron Cloncurry, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 20 Jan. 1832 in Bath, England.

Francis Nathaniel Burton was elected to the Irish parliament in 1790 for County Clare, in which were located the family estates at Buncraggy, near Ennis. After the union with Great Britain, he sat at Westminster for the same constituency between 1801 and 1808. Perhaps as a reward for his championship of the union or in recognition of his family’s prominence in local Irish politics, Burton was appointed lieutenant governor of Lower Canada on 29 Nov. 1808. For more than a decade thereafter he was content to remain in Britain and draw an income of £1,500 a year. By 1818 the provincial House of Assembly had become critical of salaries paid to absentees, but it took Colonial Secretary Lord Bathurst several years, the threat of discontinuing Burton’s salary, and possibly the promise of a knighthood to persuade the diffident lieutenant governor to repair to Quebec. Finally, in 1822 – the year he was knighted – Burton left, arriving in the colony in June and bringing with him the unexpected news that a bill for the union of Lower and Upper Canada was under discussion in London.

A courtier through and through, by 1824 Burton had sufficiently ingratiated himself with the assembly to secure an increase of salary as some compensation for condescending to reside in the colony. “Every body is pleased with his manners,” recorded Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], who added with a generous confidence cruelly belied by later events, “indeed he is in all things so courtly & well bred that he must command the respect of the better classes of society, and prove to me a powerful support.”

Burton’s brief day of administrative glory dawned on 7 June 1824 when he took over the government of Lower Canada following Dalhousie’s departure on leave to Britain. For some time past the assembly had been attempting to enlarge its power at the expense of the executive by the time-honoured expedient of seeking to appropriate all revenues raised in the colony. Hitherto the executive had preserved a degree of financial independence and administrative flexibility through its control of crown revenues derived from fees, licences, customs duties, fines, forfeitures, seigneurial dues, and the renting of government owned properties. Rarely sufficient to meet expenses, these sources of revenue were supplemented as necessary by recourse to the military chest and by the surreptitious “borrowing” of money from the revenues under the assembly’s control. Until the assembly was prepared to vote a permanent civil list, guaranteeing adequate salaries to the leading officials, successive governors had had to fight not only to maintain the integrity of crown revenues but also to frame annual money bills in such a way that even tacit recognition was not made of the assembly’s claim to appropriate them. Burton, perhaps feeling that he might further his career with a daring coup, summoned the legislature in hopes of inducing it to pass an appropriation bill that would cover the government’s expenses for one year. He was thus anxious to avoid the disputes and deadlock that in recent times had characterized Dalhousie’s discussions with the assembly on the matter.

Burton began by hammering out an agreement with the Canadian party, which dominated the assembly: the elected house would not assert its claim to the crown revenues and Burton would not press the executive demand for a permanent civil list; in the bill that was drawn up crown and provincial revenues were lumped together and the government’s estimates, after some reductions made by the assembly, were passed in early 1825 for a single year. The new bill had to be endorsed by the Legislative Council, which was normally adverse to any proposal issuing from the assembly. There Burton faced redoubtable opposition from John Richardson, a leader of the English party, which generally controlled the council. The lieutenant governor enlisted the aid of two men who were political and religious enemies: a leader of the office holders, Herman Witsius Ryland*, who felt neglected politically by Dalhousie and wanted revenge, and the Roman Catholic archbishop of Quebec, Joseph-Octave Plessis, who owed Burton a political favour for his having accepted a bill that constituted a first step towards the civil erection of parishes. Ryland brought over the British office holders in the council, while Plessis managed to bring in for the vote the decrepit and habitual absentees among the Canadian members. Richardson was defeated handily.

Burton triumphantly reported to the Colonial Office his happy settlement of a protracted controversy. However, in London Dalhousie, who had anticipated that the legislature would not be summoned until he returned, at once condemned an arrangement that, although it avoided mention of disputed rights, in his view implicitly conceded the assembly’s claim to control crown revenues. At first the Colonial Office endorsed Dalhousie’s interpretation and censured Burton for disobeying instructions, but the lieutenant governor’s denials that he had sacrificed the government’s position, eventually supported by legal opinions from the chief justice of Lower Canada, Jonathan Sewell*, and the British law officers of the crown, gradually had their effect. To Dalhousie’s chagrin and annoyance, Bathurst came to place a more charitable construction on the settlement and to dismiss the governor’s melodramatic assertion that the assembly had acted with animus and cunning. The colonial secretary may also have been mindful that Burton enjoyed royal favour because of the notorious friendship between Lady Conyngham, his sister-in-law, and George IV, who took it upon himself in 1827 to suggest that Burton be appointed governor of Jamaica, a recommendation that ministers politely ignored.

On Dalhousie’s return in September 1825, Burton left Lower Canada on an indefinite leave of absence under something of a cloud, still arguing about his salary. A reluctant resident at Quebec, he appears to have been more intent on advancing his career and financial interests than on the constitutional issues at stake in the rumbustious politics of Lower Canada. Yet for years after his departure, Canadian politicians and church leaders hoped he would return at the head of government, a dream Burton may have shared since he retained sufficient interest in the colony’s affairs to continue a correspondence with local politicians such as Denis-Benjamin Viger*, John Neilson*, and Louis-Joseph Papineau*. He did not come back, although he remained lieutenant governor until his death. Personable, gracious, and skilful with his ample Irish blarney, Burton could charm and flatter, but he had proved no match for the wily leaders of the assembly. There was much truth in Dalhousie’s judgement, despite its undisguised partiality, that “Sir F. has shewn a very weak & very vain mind – he has courted popularity in every step & in every act of his short Administration.” Again according to Dalhousie, the crafty local politicians had beaten him at his own game and, in the case of Bishop Plessis, left him “vexed and disappointed & humbugged.”

Burton’s administration, however short, had long-term consequences for Lower Canadian politics. It bequeathed to the hapless Dalhousie a bitter legacy since the formula worked out for presenting estimates had whetted the assembly’s appetite for influencing appropriations and encouraged that body all the more to resist the governor’s return to the old claims for a permanent civil list. The acute political crisis that resulted led to Dalhousie’s recall in 1828; his successor as the head of government, Sir James Kempt*, was obliged in the end to have recourse to the Burton model and the Colonial Office to endorse it in 1831.

BL, Add. mss 35729, 35734, 38751–52; Loan 57. PAC, MG 24, A64; B1, 4–6; B2, 1; B6, 1–2; MG 30, D1, 6: 669–78. PRO, CO 42/177–213; CO 43/25–26; CO 324/95. SRO, GD45 (mfm. at PAC). L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1818–27. Bath & Cheltenham Gazette (Bath, Eng.), 24 Jan. 1832. Wallace, Macmillan dict. Joshua Wilson, A biographical index to the present House of Commons . . . (London, [1806]). Taft Manning, Revolt of French Canada, 132–48.

Cite This Article

Peter Burroughs, “BURTON, Sir FRANCIS NATHANIEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burton_francis_nathaniel_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burton_francis_nathaniel_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Burroughs |

| Title of Article: | BURTON, Sir FRANCIS NATHANIEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |