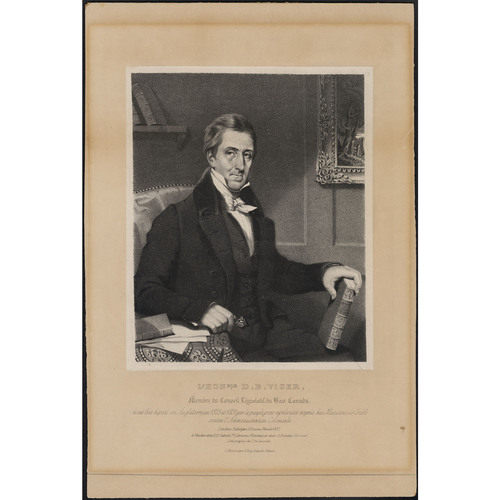

VIGER, DENIS-BENJAMIN, lawyer, journalist, essayist, and politician; b. 19 Aug. 1774 at Montreal, son of Denis Viger, a businessman and mha, and Périne-Charles Cherrier, daughter of François-Pierre Cherrier; d. 13 Feb. 1861 in the same city.

Denis-Benjamin Viger belonged to a family that, like others of the period, was moving up in the social scale and ultimately played a decisive social and political role. His father Denis, a carpenter, became a building contractor and also engaged in the making of potash, exporting it to England. Like many French Canadian and Anglophone merchants, Denis Viger was attracted to politics, and from 1796 to 1800 he represented the county of Montreal East in the House of Assembly of Lower Canada. Through his mother, a Cherrier of Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu, Denis-Benjamin Viger was related to the Papineaus. He was also a cousin of Jacques Viger*, who became the first mayor of Montreal, and of lawyer Louis-Michel Viger*, a founder of the Banque du Peuple and eventually its president.

Viger came from a small family; his only sister, Périne, died unmarried in 1820 at the age of 40. He might have followed his father into contracting on a small scale, but in 1782 the latter sent him to the Sulpicians for a secondary education. He completed his studies at the Collège de Montréal without difficulty, and then decided to enter the much sought after profession of law. From 1794 to 1799 Viger received his legal training under Louis-Charles Foucher, who was appointed solicitor general of the province in 1795, then under Joseph Bédard, a Montreal lawyer and brother of Pierre-Stanislas Bédard*, and finally under Jean-Antoine Panet*, at that time speaker of the assembly. When he was called to the bar on 9 March 1799 he had not only learned law but had acquired a taste for politics. He also had become imbued with a desire to be of service.

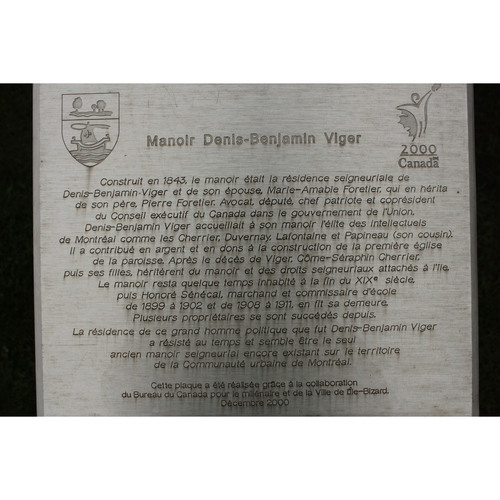

Viger was a serious young lawyer, intellectually inclined, idealistic, retiring, and often regarded as boring and awkward. Unlike Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, with whom he had characteristics in common, he was not without a flair for business. After 11 years of practising law, he was said to be “in easy financial circumstances.” But it is doubtful whether the extent of his clientele in fact accounted for his comfortable state. He had been able to count on his father’s assistance in establishing himself, and in 1808 he had married Marie-Amable Foretier*, the 30-year-old daughter of Pierre Foretier*, a seigneur and former furtrader. The Vigers were to have only one child, a daughter who died in 1814 at the age of eight months. Mme Viger was one of the legatees of Pierre Foretier’s estate, which was administered by Jean-Baptiste-Toussaint Pothier*, and from 1816 to 1842 was the subject of an interminable lawsuit complicated by Pothier’s bankruptcy. In 1842 Mme Viger finally was able to take possession of the Île Bizard seigneury, her father’s property. On his mother’s death in 1823, Viger inherited the family fortune, which included five houses and 47 acres of land in the faubourg Saint-Louis. From then on Viger was one of the most important landed proprietors in the town of Montreal. When he gave land for the establishment of his cousin, Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue*, some malicious persons cast doubt upon Viger’s disinterestedness with the rumour that this generous gesture was aimed at increasing the value of sites he owned nearby. Viger carefully administered and enlarged his fortune, which seems to have been based on landed property and to have depended less and less on his earnings as a lawyer. This love of landed property brought tangible rewards, and gave him resources not available to most of the other Patriote leaders, though they were equally enamoured of land. Although he might later confuse his own interests and those of the group around him with the interests of the nation, Viger’s career cannot nevertheless be reduced to the simple acquisition of dollars and cents. He was a bourgeois who had certain ideas and aspirations in common with the aristocracy, although he condemned it.

Viger was furthermore a young lawyer who liked to explore ideas and theories and to express them in writing, and he was ambitious in his intellectual pursuits. He bought books – at the end of his life his library contained more than 3,000 volumes – and he also read avidly. But he certainly would not have been able to find full satisfaction as a man of culture and independent means. Viger’s intellectual activity was soon dominated by his interest in political issues. His first writings, published in the Gazette de Montréal, then a bilingual newspaper, date from 1792. His publications, his association with numerous newspapers and the financial support he gave them even when he was not the owner, are evidence that his thinking and activity centred on politics and national questions. The publication in 1809 of his Considérations clearly indicated his political concerns and the degree of his commitment. Viger had not waited for professional and business success to launch himself into politics. In 1804 he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the assembly, but he did not give up and four years later he was returned in the western district of Montreal. He entered the assembly at the same time as his cousin Louis-Joseph Papineau*. Viger then began a long political career that did not end until 1858. He was among the first of the career politicians.

A member of the rising liberal professions, Viger entered political life when a nationalist ideology and political parties were beginning to take shape in Lower Canada. Like Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, he was a fervant admirer of English parliamentary institutions and of the felicitous balance within them between the three traditional principles of government: the monarchist, the aristocratic, and the democratic. His admiration for British institutions and for Great Britain was a consequence of theoretical considerations, of hostility to the excesses of the French revolution, and of aversion for Americans and their institutions, but it was also inspired by other factors. Like Bédard, he felt that the French Canadian nation was threatened by the activity of English speaking merchants and by American immigration, and that these circumstances, as well as military tensions, gave Great Britain and British institutions a more significant role as a protective framework for the French Canadian nation. In his view, British institutions favoured the development of French Canadian culture, its fate being linked with the preservation of the old régime and the advancement of the French élite. When the War of 1812 broke out, Viger joined the French and English middle class and élite in the movement of national and imperial solidarity against the American invader. Viger had been appointed a lieutenant of militia in 1803 and was promoted captain at the time of the War of 1812. He was later raised to the rank of major, and finally retired from the militia in 1824 for reasons of health.

The Parti Canadien that Viger joined was a political group whose centre of decision-making was initially at Quebec, and whose leadership came from that city. At this period, the factors encouraging the growth of nationalism were operating with the greatest force in the Quebec region, among both the French Canadian middle class and peasants. Radical thinking and action were also most in evidence there. In this respect, Montrealers seemed behind the times. It must be noted too that the formation of the Parti Canadien was complicated by Quebec-Montreal rivalry. Viger belonged to a group of Montreal politicians who not only were aggrieved by the Quebecers’ supremacy, but deplored the extremist tendencies of Bédard and those around him. The imprisonment of Bédard and the other editors of Le Canadien in 1810 aroused violent anger against Governor Sir James Henry Craig*, but does not seem to have horrified this Montreal group as much as has been thought today, or as they were willing to imply. Bédard’s withdrawal from politics set in motion a long and bitter struggle for the leadership of the Parti Canadien, lasting until 1827, from which Montrealers emerged the winners. Papineau’s victory was not assured until that date.

There were many candidates to succeed Bédard, particularly in the Quebec region. Although Governor Sir George Prevost* managed to persuade the Parti Candien to support the war effort, the battle for the party’s leadership still went on, under the surface or openly, according to circumstances. A first successor emerged from Bédard’s immediate circle, among his English speaking friends who were considered almost “true Canadiens” by the Quebec leader. Bédard maintained close relations with John Neilson* and Andrew* and James Stuart*. The latter, a brilliant lawyer, outstanding speaker, and ambitious man whose desire for rapid advancement had been frustrated by Governor Craig, adopted Bédard’s policy, but used a different strategy. Instead of raising the question of ministerial responsibility from a broad constitutional point of view, as his predecessor had done, he made use of the technique of impeachment against judges Jonathan Sewell* and James Monk*, accusing them of usurping legislative authority and abusing their office and stressing Sewell’s misdeeds as adviser to Craig. But although Stuart lived in Montreal and had considerable local support, he did not really succeed in winning recognition as a party leader. The Montrealers were not willing to see their party, a nationalist party, led by an Anglophone and a radical.

Did Viger contemplate leadership of the party during this period? It would not be surprising if he did so, for he was not without ambition. Yet Viger, whom political opponents characterized as having “long speech and long nose,” lacked colour and self-confidence though he was respected. To his friends, he was not impressive when compared with the young and arrogant Papineau. The swing towards Papineau first became evident at a time when the instability of the party and the prevailing situation made a radical policy appear dangerous. The party did not have the strength to confront, as it had in 1810, the government, the merchant faction, the clergy, and the nobility. A policy of conciliation towards the French Canadian ruling classes was indispensable. Moreover the clergy increasingly felt the need to diversify its support. The Parti Canadien’s objective of rallying all the groups which its leaders considered part of the nation did not, however, exclude a search for support among Anglophones. For from 1815 on the rapid increase of the English speaking population in the towns through immigration threatened to deprive the Parti Canadien of its urban roots and to make it appear to be a party with an exclusively rural base and ideology. Although Papineau belonged to the Montreal section of the party which became more influential as the centre of socioeconomic and ethnic conflict moved towards that city, he was obliged to take all these variables into account to command attention. His initial success was no doubt due to his personal gifts, and the particular circumstances that gained him the support of certain governors – in 1815 he was elected speaker of the House of Assembly, and three years later he began to emerge as Bédard’s moderate and reform successor – but he also seems to have had a remarkable sense of timing and of the process of change. Ministerial responsibility was temporarily set aside as an avowed political objective, and replaced by the issue of supply bills, which became a polarizing force for political action. To attract the votes of Irish Catholics and liberal Anglophones, and to win the support of Quebecers, he formed a close association with John Neilson, who became Papineau’s lieutenant in the Quebec region. How can Viger’s role at this time be defined, except in relation to the leadership question in the Montreal region?

Beyond any doubt, Viger was one of the principal leaders of the Parti Canadien. He had a major share in shaping its ideology, perhaps for some years, and he undoubtedly was instrumental in planning for parliamentary sessions and electoral campaigns. In this connection, Viger had realized that newspapers played a vital part in the diffusion of ideas, programmes, and slogans. In the House of Assembly he was active in debates – at the risk of sending his audience to sleep – or, more often, in house committees. Viger made his presence felt when it was necessary to defend the institutions of the old régime: the seigneurial system, the customary law of Paris, or the rights and privileges of the church. His hostility to any basic reform in these areas, and in particular to the establishment of registry offices, was not exceeded in vigour. During the quarrel over the establishment of the diocese of Montreal, a conflict which set Bishop Lartigue, the successive bishops of Quebec, and the French Canadian clergy against the Sulpicians, who tended to support the government, Viger became one of the chief proponents of the myth of the good national clergy. He not only upheld Lartigue’s cause, but acted as liaison between the bishop of Montreal and the leaders of the Parti Canadien. He continued to serve as intermediary between his two cousins even after 1830, when relations between the clergy and the party deteriorated.

After 1815 the influence of the Montreal section of the Parti Canadien, for which Viger was one of the most active fieldworkers, increased steadily, but it does not follow that the Quebecers had lost hope of resuming the leadership. This possibility became apparent at the time of the 1822 union crisis. If there was one event that crystallized opinion, it was surely this one. French Canadian nationalists and defenders of the society of the old régime (seigneurs, clerics, professional people), liberal Anglophones, and Irish Catholics – all joined in a movement of intense opposition to the plan for union of the Canadas. Committees were set up in each district to mobilize the population, draft addresses, get petitions signed, and choose delegates. Viger was the most prominent leader after Papineau; indeed the advocates of the union proposal gave the name of Vigerie to the opposition movement. Viger fought with pen and oratory. He helped Dr Jocelyn Waller* launch the Canadian Spectator in October 1822, as a means of organizing the opposition, and on 7 October, on the Champ de Mars, he made an anti-union speech which aroused his audience. But although the situation was acknowledged to be critical, unanimity was only achieved with great difficulty when it came to choosing delegates who would take the petitions to England. The Quebecers did not want decisions to be imposed by the Papineaus and the Vigers. Finally John Neilson, who was “a good Englishman” to quote Papineau, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, then a judge (who in the event would be unable to obtain leave), and Louis-Joseph Papineau won the votes of the various local factions.

The departure of Papineau, the speaker of the assembly and leader of the party, led to a resurgence of the Quebec-Montreal rivalry. The Quebecers were determined to use his absence to recover their control of the party. Viger would have liked to become speaker and perhaps emerge as an eventual leader. But he came into conflict with another Montreal group, directed by Louis Bourdages*, so that Joseph-Rémi Vallières* de Saint-Réal, a Quebecer, was elected speaker of the house, while Andrew Stuart seems to have acted as interim leader. When the latter left for Europe, Vallières de Saint-Réal took over both offices, and proposed to hold them as long as possible. All Papineau could do when he returned was to note that the Quebecers were masters of the political scene. He even thought of withdrawing from public life. But the union crisis had helped to increase the prestige of Neilson and Papineau, and the latter had no difficulty, when the right moment came, in resuming the role of leader. His position was even strengthened. Like Bédard, Vallières de Saint-Réal accepted an appointment as judge.

During the governorship of Dalhousie [Ramsay*], the struggle intensified around the question of supply; other Montreal leaders became prominent and surpassed Viger in influence in some respects. Augustin Cuvillier*, an auctioneer, businessman, and owner of substantial property, became the financial expert of the Parti Canadien. Cuvillier was ambitious, and prompted by success he set his sights high. His disappointment would be intense when the supply question ceased to have any real significance, but meanwhile he was making his presence felt. After the great electoral success in 1827, Papineau decided to make a determined effort against Governor Dalhousie, and revived the scenario of 1822: the formation of regional committees, signing of petitions in all areas, and appointment by these committees of delegates to express and defend the party’s point of view in England. Neilson was again chosen, and Cuvillier and Viger were appointed his assistants. Significantly, the final choice of these three delegates took place in Montreal, at a meeting on 24 Jan. 1828. This mission arrived in England in March, under exceptionally favourable circumstances. The idea of reform was in the air, and during an interview the colonial secretary, William Huskisson, announced to the three delegates the setting up of a House of Commons committee which was to meet between 8 May and 15 July, to investigate Canadian problems and propose solutions. The three were summoned in turn to appear before this committee of 21 mps. Viger was heard on 7 and 10 June. In his lengthy statement, he asserted that the old French law and the seigneurial system should be retained, asked that changes be made to allow French Canadians easier access to lands in the Eastern Townships, and suggested a reform of the Legislative Council to make it more representative.

On 22 July the committee presented its report, and on most points recognized the validity of the claims of the majority that controlled the House of Assembly of Lower Canada. On the question of supply, the Patriote party’s victory was almost complete. His task completed, Viger travelled in France and Holland, and returned with the idea for a work which was published in 1831 under the title of Considérations relatives à la dernière révolution de la Belgique. In London Viger had projected the image of a moderate, “reasonable” man, according to Tory mp Thomas Wallace. Did this image induce Sir James Kempt*, the administrator of Canada, to offer him a seat on the Legislative Council as soon as he returned, in order to show the government’s impartiality, improve relations between the houses, and doubtless weaken the Patriote party? We do not know, just as we do not know why Viger accepted. On his return to Quebec in December 1828, did Viger believe in the good faith of Great Britain, did he think he would be more useful if he agreed to be a member of the Legislative Council, or again, did he suppose that his future prospects would be better in the upper house than in the assembly? We do not know. In any case in August 1829 he accepted Kempt’s offer. Viger took his seat in the Legislative Council in January 1831, but did not hold it long, as we shall see. He only had time to win a verbal battle with John Richardson*, who was opposed to the popular election of municipal officers. His diatribe against absolute power earned him the nicknames of Marat and Robespierre in the English press, nicknames out of keeping with his conciliatory spirit and moderation. The radicalizing of the Patriote movement, in process for some years, had come to involve a fundamental re-assessment of the Legislative Council.

The struggle for the control of supply was in reality only one stage of along confrontation in which the assumption of power by the French Canadian middle class was at stake. Bédard had initially conceived his strategy within this overall perspective. Subsequently, circumstances had made it necessary to pursue more limited objectives, centred on the effort to gain participation in power. But as soon as London supported the Patriote party on the question of supply and proposed a solution that would safeguard the aspirations of all sides, Papineau declared that control of finance was no longer a priority for his party and did not respond to the English government’s offer. From then on he adopted a new strategy, which involved radicalizing the Patriote party’s action and ideology. Although there was still a concern to retain traditional Anglophone bases of support this strategy aimed at putting power into the hands of the French Canadian middle class, and pointed towards independence. The assurance and justification of such a victory lay in the application of the elective principle at all levels where power was exercised. It therefore became a primary objective to make legislative councillors subject to election. But in 1828 Papineau was not in a position to take this drastic step. This radical orientation implied a major constitutional change, whereas the Parti Canadien had always objected to any alteration of the 1791 constitution, and the Patriote party quite recently had proclaimed its inviolability. He also had to convince the other leaders of the party of the necessity for this redirection, and to make the electorate aware of the issue of an “elective Legislative Council.” The effort was launched through a series of bills concerning schools, parish councils, urban municipalities, and local institutions, which all stipulated the election of officers by property owners. Then, in a second phase, while frequently repeating republican professions of faith and paying homage to American institutions, Papineau started a campaign of systematic disparagement of the councils of the government, and in particular the Legislative Council. An elective status for its members was then put forward as the only solution to the problems of Lower Canada. The Legislative Council was the symbol of English exploitation, but, if elective, it would become the symbol of justice and of French Canadian power. The “elective Legislative Council” was the slogan that dominated the general election of 1834, and gave Papineau and his party an extraordinary success.

This change of strategy, with its harder line of action, was helped by deteriorating economic conditions, the demographic context, and the sharpening of disparities between ethnic groups in both town and countryside. It also reflected major changes in the leaders of the Patriote party, and aroused aggressive reactions from the opposition. The restless atmosphere in the province stimulated the former leaders to more vigorous action, and produced new ones, nationalist, liberal, or radical, who sought an all-out clash with Great Britain. Revolution was talked of. It is indisputable that Papineau was increasingly influenced by men such as Ludger Duvernay*, Augustin-Norbert Morin, Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, Charles-Séraphin Rodier*, or Amury Girod*, rather than by older men such as Viger. Papineau tried, but it was in vain, to keep the support of the liberal Anglophones, the Irish Catholics, and the American settlers in the townships. He established a closer relationship with Robert* and Wolfred Nelson. The Irishman E. B. O’Callaghan* even became his right-hand man. Obviously, this radicalization of the Patriote movement also meant ruptures and defections. The long association of Papineau and John Neilson was broken. Andrew Stuart was the first to pass to the other camp; Cuvillier and Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel followed. But the strongest reactions came from the clergy and the British government, and even from the English supporters of the Patriote party. Once again, what was Viger’s role in all this?

On 28 Feb. 1831, one month after Viger took up his duties as a legislative councillor, Louis Bourdages, probably at Papineau’s instigation, proposed to the assembly that Viger should be appointed its agent in England. On 28 March the assembly, dispensing with the Legislative Council’s assent, made the appointment by a resolution; its action led Lord Aylmer [Whitworth Aylmer*] to refuse Viger a letter of introduction to Lord Goderich. On 13 June Viger was in England, and secured François-Xavier Garneau as his secretary. The circumstances of – his stay in London were in marked contrast to those of 1828, when the British authorities had been receptive. In 1831 they were convinced that the reason the Patriote party was rejecting the reforms it had offered and instead formulating unacceptable claims was that the party was about to collapse. Hence the radicalization of the Patriote movement was interpreted as a desperate reaction to safeguard the prestige of a few ambitious leading figures. As a consequence, although the British were preoccupied with their own parliamentary reform, Viger was able to communicate fairly easily with Lord Goderich. He met former administrators such as Sir Francis Nathaniel Burton* and Sir James Kempt. He kept in contact with the Radicals, who were seeking to take advantage of the discontent of the Canadas. But as English official circles became convinced that the Patriote movement was above all a nationalist movement, seeking power for a particular ethnic group and a particular social class, and aiming at political independence and the subjugation of the English minority, Viger’s position became increasingly difficult. In 1833 E. G. G. Stanley, the secretary of state for the colonies, gave Viger to understand that he had nothing more to learn from him. The arrival in the spring of 1834 of Augustin-Norbert Morin, who brought the petitions inspired by the assembly’s 92 Resolutions, in no way modified the British government’s attitude. Between 12 May and 13 June 1834 Morin was called to testify before a commons committee on six occasions. Unable to count on the point of view of a “good Englishman” like John Neilson, who was now associated with the defenders of the constitution, Viger could not move the government. Disappointed by the turn of events, Viger returned to Canada on 1 November, in the middle of an election campaign. The warm welcome he received from an enthusiastic Montreal crowd was not enough to prevent him and Papineau from realizing that his mission had failed. In 1835 the radical John Arthur Roebuck*, much more aggressive than Viger, was instructed by the assembly to defend the interests of Lower Canada in England.

Despite his 60 years and his failure in London, Viger did not retire. Perhaps he was exhilarated by the great electoral victory of 1834. The confrontation between the British government and the Patriote party was taking a much more serious turn. The idea of acquiring independence by revolutionary means was spreading among militant Patriotes. It is certain that at this period Viger was not in retirement, and was following events closely. In 1834 he was active in the correspondence committee in Montreal. As part of the grand campaign designed to bring down the English business bourgeoisie, Viger published his Observations, which recommended boycott of imported products subject to tax, development of local industry, and the practice of “purchase at home.” The founding of the Banque du Peuple, a symbol of the economic regeneration of French Canadians and an instrument for the economic and political ambitions of a small group of well-endowed Patriotes, did not escape Viger’s notice. Its ten-dollar bills were even printed bearing the effigies of Mercury, the god of trade, and of Viger. Moreover, in 1835 Viger replaced his cousin Jacques as president of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, and presided at its annual banquet until 1837 [see Jean-François-Marie-Joseph MacDonell]. In 1835 he had been appointed president of the Union Patriotique, which sought responsible government, the election of legislative councillors, and the abolition of monopolies, particularly that of the British American Land Company.

The British parliament’s adoption in March 1837 of the Russell Resolutions, which allowed the governor to draw upon public funds without the assembly’s assent and categorically refused the reforms sought by the Patriote party, forced the leaders of that party to take up a revolutionary strategy. The extremists, the radicals, and others were ready to move immediately, and to undertake to overthrow the government. But more realistic minds prevailed. They knew that the mass of the people needed to be mobilized skilfully for new and more demanding objectives. To expect a spontaneous popular uprising did not seem useful in the circumstances. Preparing the people psychologically for any eventuality had to have as accompaniment the creation of revolutionary cadres, and of an organization for matériel. Equally serious problems existed at the leadership level. Since 1835 the chief Patriotes of the city of Quebec had not only held themselves aloof but had expressed their dissent. It was therefore necessary to reconstitute the leadership in the Quebec region and this was to be Morin’s responsibility. The Patriote leaders then rallied around a plan which set a revolutionary process in motion but left the door open to possible capitulation by the British government. In this perspective, large meetings are only a stage in the advance of a revolutionary movement. Viger must have been involved in all these discussions and must have shared in one way or another in all the decisions. He was too close to the top level of the party, the permanent central committee, for these proceedings to have escaped his notice. He was one of those who called the Saint-Laurent meeting of 15 May 1837. But generally speaking, perhaps because of his age as well as for other reasons, Viger like many others stayed in the background. Nevertheless he too was compromised.

As public meetings continued to be held, so-called legal opposition quickly became a fiction. The extremists did not worry about precautions, and openly advocated recourse to arms. The radicals went further, and called for the abolition of tithes, of the seigneurial régime, and of the customary law of Paris. Thus the drive towards revolution progressed much more rapidly than had been foreseen, and took a turn which could be menacing for the nationalist élite, among them some of the directors of the Banque du Peuple, who thought solely of political independence for the benefit of the French Canadian middle class. Papineau and Viger were doubtless somewhat worried by these social tendencies, but the acceleration of the revolutionary movement also served their ends. La Minerve, a paper financed by Viger, not only did nothing to slow the process or to urge the radicals to be prudent but actively stirred up discontent. Hence the meeting at Saint-Charles on 23 Oct. 1837, where the Patriote leaders agreed to hold a great rally on 4 December, “after the freeze-up,” occasioned no clash between radicals and nationalists over tithes or the seigneurial régime. When, following this meeting, the bishop of Montreal issued a pastoral letter condemning the revolutionary designs and the ideology of the Patriotes, it was Viger who undertook to reply. Annoyed by the defection of the “good national clergy,” he entitled his article in La Minerve on 17 Aug. 1837: “Deuxième édition de la proclamation Gosford sous forme d’un mandement de l’évêque de Montréal.” He discussed the implications of the pastoral letter, drew attention to the clergy’s inconsistency and its links with the government, and concluded with a story suggesting that “A day will perhaps come when His Excellency will be the first to intone the Domine Salvum Fac le gouvernement provisoire.” Viger did not attend the Saint-Charles meeting; nor was he a member of the Association des Fils de la Liberté. The latter nevertheless used some of his land for their military exercises.

For a long time the government had tended to interpret the activities of the Patriotes as blackmail intended to frighten it. In fact the British authorities, less clear-sighted than the clergy and the local English speaking minority, had believed that the Patriotes were incapable of a revolutionary adventure. But from the beginning of November 1837, and particularly after the riot of 6 November, it was no longer possible to ignore the real intentions of the Patriote leaders. At this point the government’s reaction, which Étienne Parent*, the editor of Le Canadien of Quebec had predicted, began to take shape. The rumour, then the certainty, that the principal leaders would soon be arrested quickened and changed the tempo of events. All this activity enables us to understand the excitement in Montreal, and particularly the relations between Viger and the revolutionary movement.

There were earnest consultations between Papineau and the chief figures in the party. The testimony given by Angélique Labadie, dit Saint-Pierre, a servant in Viger’s household, not only agrees with what we know from other sources but also sheds a curious light on these critical moments. The first conversation she mentions, between Papineau, Viger, and Côme-Séraphin Cherrier* – which no doubt took place shortly after the Saint-Charles meeting – reveals the economic and political ambitions of this “family compact,” and shows how persistent was the hope that the British government would capitulate before things went too far. The second conversation reported, between Papineau and Viger, enables us to grasp better Papineau’s personal ambitions and the existence of a plan for revolution whose dénouement was to occur after the freeze-up. Viger is said to have stated “that it was necessary to proceed more quietly and to wait for the freeze-up, that at that time the blast of a whistle would rally large numbers of habitants and thousands of Americans to their cause, and that they would soon be masters of the country.” The third conversation took place in more tragic circumstances, when Viger informed Papineau that a warrant of arrest was about to be issued against him, and advised him to leave the city. Viger may well have said on this occasion “that the sun shone for everybody and that it would shine again for them, and that perhaps he would see the day when they would be victorious; . . . that they must call upon the Supreme Being to sustain them in their cause; . . . that he would not be worried if he saw the streets stained with the blood of those who did not share their political views, and who were . . . nothing but reprobates.” Such exchanges are frequent at times when events seem to be moving fast. Papineau, moreover, did not talk solely with his intimate friends and the Patriote leaders; he also had discussions during the few days preceding his departure from Montreal with an envoy of William Lyon Mackenzie. One day Jesse Lloyd* arrived with the greatest secrecy in Montreal and went to Papineau’s house; the latter hastily summoned Wolfred Nelson and E. B. O’Callaghan. Papineau is said to have asked his son, once Lloyd had left, never to utter a word about the visit. In a letter of September 1844 addressed to O’Callaghan, Mackenzie alluded to the results of this meeting: “When yourself and friends sent up [an emissary] to Toronto in Nov. 1837 to urge us to rise agt. the British Govt. it would certainly not have come to my thoughts that the men who did that would in the event of failure make a treaty with Engd. for the patronage of Canada to themselves and to our tory enemies. . . .” In this letter Mackenzie clearly associated the name of Viger with that of Papineau: “the loyal Papineaus, Vigers, Bruneaus.”

Viger’s role in the subsequent revolutionary events remains to a great extent obscure. We do not know the nature of his relations with the directors of the Banque du Peuple, which may be assumed to have been close, nor do we have exact information about the connection between the Banque du Peuple and the revolutionary movement. The only really explicit testimony is that of Abbé Étienne Chartier*, who denounced the treason of the directors of this institution. Chartier accused them in particular of having refused at the last moment to finance the insurrection. Might the intervention of English troops before the anticipated moment, or the fear of seeing an anti-feudal movement develop, underlie the withdrawal of the Banque du Peuple, as Chartier contended? What was the link between the arrest of bank president Louis-Michel Viger, the lightning trip of Édouard-Raymond Fabre* to Saint-Denis, and the flight of Papineau and O’Callaghan at the start of the battle?

In any case, Viger did not remain inactive. After La Minerve ceased publication in November 1837, François Lemaitre published two papers in Montreal: La Quotidienne, from 30 Nov. 1837 to 3 Nov. 1838, and Le Temps, from 21 August to 30 Oct. 1838. These papers, which were accused of spreading discontent and diffusing ideas concerning independence, were said to be Viger’s property. Lemaitre occupied a house belonging to Viger and was active in the Association des Frères-Chasseurs, which was planning the second insurrection under the direction of Robert Nelson and Dr Cyrille-Hector-Octave Côté*. Were mere coincidences used by political opponents to incriminate Viger? The absence of direct evidence against him does not mean that he was completely innocent. It is certainly possible that he had used tactics similar to those of Papineau, who let the radicals use his name in 1838 as a symbol of the revolution and who, though he kept apart, maintained relations with certain revolutionary groups, out of fear that the movement might slip from his control completely. For it must not be thought that the second insurrection mobilized only radicals. Many – in fact the great majority – did not accept the radical ideology but joined the revolutionary adventure, telling themselves that the ideological differences would be settled after victory. In 1838, as in the preceding year, the Patriote movement was in essence nationalist, and the radicals had no greater success in getting their social message across. Viger, whose house had been searched on 18 Nov. 1837 but who had not been bothered subsequently – and who had indeed been visited frequently by Stewart Derbishire In May 1838 and had received Charles Buller* and Edward Ellice Jr to dinner on 23 June – was thrown into prison on 4 Nov. 1838 when Sir John Colborne proclaimed martial law again. The Herald denounced him as the owner of seditious newspapers. On 18 December the superintendent of police, Pierre-Édouard Leclère, offered to have him released on bail, with a promise of good conduct. Viger reacted as Bédard had in Craig’s time, and demanded a trial. He remained in prison until 16 May 1840. During the first two months of his detention, Viger was not permitted to see anybody. He was not allowed to play the flageolet, his sole form of amusement. In August 1839 he was forbidden to exercise in the prison yard, despite the presence of soldiers. He could not have paper, pen, or newspapers.

The failure and disintegration of the revolutionary movement allowed the British government to enforce a solution which had been envisaged as early as 1810 by Anglophone businessmen and was now proposed by Lord Durham [Lambton*]: the political union of the Canadas. The mere notion of union evoked a series of tragic images. To the clergy, union meant the Protestant peril, threat to the culture, and destruction of the society of the old régime. The seigneurs shared these fears, but the lay élite, whether they favoured the institutions of the old régime or not, thought first of the cultural threat. When the union of the Canadas was finally decided upon in 1840, the French Canadian population had already begun to redefine itself in terms of this event which was so charged with symbolism. Although the union might eventually prove to be a poor method of cultural assimilation, it inaugurated a period of economic, institutional, and political change in which the different strata of the population of the two Canadas would share in one way or another.

Did Viger, his health impaired by his long detention, think of leaving politics when he came out of prison? If he did, the plan of union, a plan he had bitterly fought for 20 years, had only to appear again to give fresh impetus to this tenacious man. He quickly published statements in 1840 to clear his reputation and to cast upon his enemies sole responsibility for illegal acts committed under the impulse of the moment and as a result of much injustice. From 1840 on, with the support of L’Aurore des Canadas, then the only French newspaper in Montreal, he attacked the Special Council for pursuing a tyrannical policy, and prepared to come back into politics. One can understand why political veterans like John Neilson and Viger, who had long been companions in battle, and for nearly ten years opponents, appeared at first unable to accept the fait accompli, and found themselves side by side in their denunciation of the union and of the reasons behind its establishment. Their social conservatism prevented their contemplating annexation to the United States, or cooperating with the Upper Canadian Reformers to obtain ministerial responsibility. La Fontaine, who in 1837 had thought of supplanting Papineau and who later had continued to scheme in order to emerge as national leader, did not however have the same reasons as his elders or the diehard republicans to be inflexible. He favoured the abolition of the seigneurial régime and was able to look upon the union with more optimism. Like the Reformers of Upper Canada with whom he wanted to ally himself, he felt that the old colonial system was about to collapse, and that the philosophy of free trade, once accepted, necessitated the political autonomy of the colonies. In his mind, responsible government implied not only a certain autonomy in relation to Great Britain but a sharing of power between ethnic groups. In fact La Fontaine, unlike Neilson and Viger, acted in accordance with a political concept and strategy.

In the 1841 election the anti-unionists and the reformers of Canada East combined against the Tories, and managed to elect 20 of 42 representatives; Viger was returned in the county of Richelieu. The group was dominated by John Neilson and Viger and included few supporters of La Fontaine, himself defeated. Viger gave the impression of being a leader. He denounced the union because it did not respect proportional representation and restricted the use of French. He compared Canada East’s situation to that of Belgium which, upon union with Holland before 1830, had had to discharge part of the latter’s debt. On 3 Sept. 1841 he also supported Robert Baldwin*’s resolutions defining responsible government. However, the situation did not work out to Viger’s advantage but to that of La Fontaine, whose Upper Canadian friends had him elected in York County. After the arrival of the new governor, Sir Charles Bagot*, in 1842, the Reformers’ position improved, and the principle of ministerial responsibility, although not formally recognized, shaped the relations between the ministry and the governor. From the first Bagot helped undermine the influence of Viger and Neilson through appointments of French Canadians to office. But this rapid evolution of the political system was peculiarly fragile because it depended on the personality of the king’s representative and his grasp of the Canadian context. Consequently it came almost abruptly to a halt under Bagot’s successor, for Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, instructed by Lord Stanley, proposed to govern and to retain the privilege of distributing political favours. In November 1843 La Fontaine and Baldwin resigned. Viger’s behaviour on that occasion finally led to his emergence as a political leader.

Viger decided to accept on 7 Dec. 1843 the offer of Metcalfe, “an enlightened despot,” and form a ministry with the moderate Conservative William Henry Draper*: a baffling decision. Until 1830 Viger had shared Neilson’s political ideas; subsequently he had favoured responsible government and had nibbled at republicanism. With such antecedents, Viger could have done battle in any group, except the one directed by Metcalfe. There were many French Canadians who cried treason. William Lyon Mackenzie was as hard on Viger as on Papineau, claiming “now we see his friends and family monopolizing the patronage of Canada under absolutism.” When Viger was forced to explain his political ideas, he spoke of his admiration for American institutions but rejected annexation. He accepted the theory of responsible government but finally reverted to Neilson’s ideas on the British constitution. In the end Viger put his trust in the-idea of a benevolent and open-minded governor who, in his opinion, would take into account the majorities in both sections of the province. Ambition, social conservatism, and hostility to La Fontaine apparently explained the readjustment of his political thought to the circumstances of the moment.

The task undertaken by Viger was considerable, even if he enjoyed the governor’s confidence. While trying to convince the public of the validity of his thesis through his actions, he also had to rally influential people around him. He even thought of repatriating Papineau, and started negotiations to get him the £4,500 of arrears in his salary as speaker of the assembly. The former Patriote leader was not averse to collecting the arrears but refused to accept the role offered him. On 15 June 1844 Le Fantasque wrote: “God created the world in six days; for nearly nine months now M. Viger has been trying to create a ministry – he is doing it no doubt in his own image: without end.” Viger finally chose Denis-Benjamin Papineau* to become commissioner of crown lands on 2 Sept. 1844.

The difficulties Viger encountered in creating a dynamic and representative entourage were increased by the results of the elections of October 1844. Of his party’s candidates, only Papineau succeeded in getting elected. Viger himself was defeated in Richelieu, and could not sit in the house until July 1845, after being elected at Trois-Rivières. It is true that the Tories had obtained a majority in Canada West but it is hard to believe that the results in Canada East could have strengthened the argument for double majority. Viger’s system was based entirely on the good faith of the queen’s representative. Whatever assessment one may make of the Metcalfe administration, it is impossible not to recognize the precarious and uncomfortable situation in which the two cousins found themselves. On 17 June 1846 Viger resigned, succumbing to the pressure of the majority. L’Aurore des Canadas, a newspaper which supported him, was falling into discredit. For some years La Minerve (revived in 1841) had been applauding La Fontaine’s growing success.

On 25 Feb. 1848 Viger was again appointed a legislative councillor. He would be 74 in August. He lived on Rue Notre-Dame, a little east of Rue Bonsecours, in a two-storey stone house he had bought in 1836 for £2,800. Tired of political struggles – he did not attend the sessions of the council from 1849 to 1858, when his seat was proclaimed vacant – he wanted to enjoy the pleasures of a peaceful retirement with his wife. The latter continued to devote herself to charitable works: one of six founders of the Institution pour les Filles Repenties, and president of the Orphelinat Catholique de Montréal (1841–54), she cared about the welfare of the needy. Viger himself gave less and less attention to politics. On 15 March 1849 he spoke for the last time in the council, against the Rebellion Losses Bill contending that the province was already too burdened with debt. He intervened again, in the newspapers, to denounce annexation to the United States, then in 1851 to oppose the suppression of rent payments to the seigneurs, which he likened to an act of pillage. Fatigue, illness, and infirmity caused him to draw farther and farther away from politics. He read, and perhaps still played the flageolet. Louis-Joseph-Amédée Papineau, in 1852, considered his library and picture gallery two of the finest collections in Canada, and allowed that his wine cellars were famous. In retirement this theorist and politician remained a man of culture, a lover of art and good living, and, as Papineau had noted in 1835, a man with a conciliatory and moderate spirit but also a man of tenacity and ambition. He did not read novels, for which he had little liking, but was deeply interested in history and law, two disciplines which had shaped him.

The death of his wife from cholera on 22 July 1854 saddened his old age. His last public act was to participate in the financing of L’Ordre, a newspaper founded by Cyrille Boucher and Joseph Royal*. Perhaps by this gesture he wanted to emphasize the importance he had attached all his life to the written word as an instrument of education and propaganda. It is possible, however, that this tenacious man, by sharing at the age of 84 in the creation of a newspaper that was Catholic, moderate, nationalist, and respectful of established authority, landed property, and agriculture, wished to ensure his work would continue and that the values for which he had fought would triumph. Viger passed away quietly on 13 Feb. 1861, at the age of 86 years and six months. He left his fortune to his cousin Côme-Séraphin Cherrier and his library to the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. Shortly after his death the Montreal Gazette expressed the opinion that the essence and the justification of his political activity were to be found in “a desire to secure the blessings of free government for his fellow countrymen.”

Denis-Benjamin Viger rarely signed his works, but he sometimes used the pseudonym “Un Canadien.” His works include: Analyse d’un entretien sur la conservation des établissements du Bas-Canada, des lois, des usages, &c., de ses habitans (Montréal, 1826); Considérations relatives à la dernière révolution de la Belgique ([Montréal], 1831; 2e éd., 1842); Considérations sur les effets qu’ont produit en Canada, la conservation des établissemens du pays, les mœurs, l’éducation, etc. de ses habitans; et les conséquences qu’entraîneroient leur décadence par rapport aux intérêts de la Grande Bretagne (Montréal, 1809); La crise ministérielle et Mr. Denis Benjamin Viger . . . (Kingston, Ont., 1844); Mémoires relatifs à l’emprisonnement de l’honorable D. B. Viger (Montréal, 1840); Observations de l’hon. D. B. Viger, contre la proposition faite dans le Conseil législatif, le 4 mars, 1835, de rejeter le bill de l’Assemblée, pour la nomination d’un agent de la province (Montréal, 1835); Observations sur la réponse de Mathieu, lord Aylmer, à la députation du Tattersall . . . sur les affaires du Canada, le 15 avril, 1834 (Montréal, 1834).

[The major Quebec archives and the PAC hold numerous documents concerning the career of Denis-Benjamin Viger. The following papers of pre-confederation politicians at the PAC (MG 24) were particularly helpful: the Viger papers (MG 24, B6), the Papineau papers (B2), the Neilson papers (B 1), and the Cherrier papers (B46). The Papineau and Bourassa collections at the ANQ-Q include newspaper articles written by Viger. Also important are the Fonds Viger-Verreau at the ASQ and Viger’s correspondence with Bishop Lartigue at the ACAM. a.l. and f.o.]

Bas-Canada, chambre d’Assemblée, Journaux, 1832–35. Siège de Québec en 1759, copie d’après un manuscrit apporté de Londres, par l’honorable D. B. Viger, lors de son retour en Canada, en septembre 1834–mai 1835 (Québec, 1836). [Ross Cuthbert], An apology for Great Britain, in allusion to a pamphlet, intituled, “Considérations, &c. par un Canadien, M.P.P.” (Quebec, 1809). F.-X. Garneau, Voyage en Angleterre et en France dans les années 1831, 1832 et 1833, Paul Wyczynski, édit. (Ottawa, 1968). [Sir Francis Hincks], The ministerial crisis: Mr. D. B. Viger, and his position, being a review of the Hon. Mr. Viger’s pamphlet entitled “La crise ministérielle et Mr. Denis Benjamin Viger, etc. en deux parties” (Kingston, [Ont.], 1844). Monet, Last cannon shot. Fernand Ouellet, Éléments d’histoire sociale du Bas-Canada (Montréal, 1972). É.-Z. Massicotte, “Les demeures de Denis-Benjamin Viger,” BRH, XLVII (1941), 269–75. Fernand Ouellet, “Denis-Benjamin Viger et le problème de l’annexation,” BRH, LVII (1951), 195–205; “Le mandement de Mgr Lartigue de 1837 et la réaction libérale,” BRH, LVIII (1952), 97–104; “Papineau et la rivalité Québec-Montréal (1820–1840),” RHAF, XIII (1959–60), 311–27.

Cite This Article

Fernand Ouellet and André Lefort, “VIGER, DENIS-BENJAMIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/viger_denis_benjamin_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/viger_denis_benjamin_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Fernand Ouellet and André Lefort |

| Title of Article: | VIGER, DENIS-BENJAMIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |

![Denis-Benjamin Viger [image fixe] Original title: Denis-Benjamin Viger [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.2953.jpg)