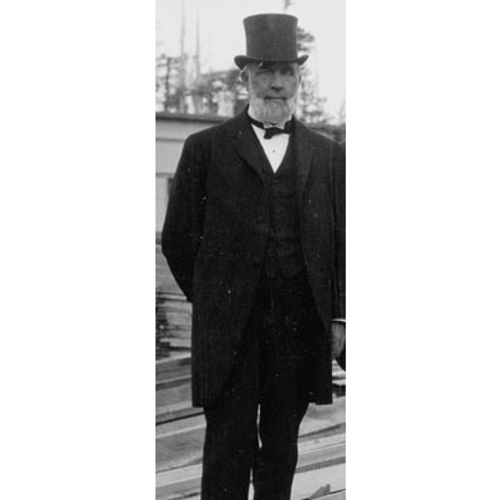

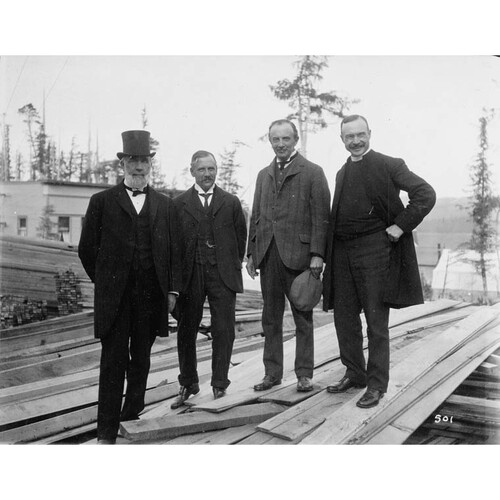

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

COX, GEORGE ALBERTUS, capitalist; b. 7 May 1840 in Colborne, Upper Canada, son of Edward William Cox and Jane Tanner; m. first 28 May 1862 Margaret Hopkins (d. 1905) in Peterborough, Upper Canada, and they had three sons and two daughters; m. secondly 14 April 1909 Amy Gertrude Sterling in Toronto; d. there 16 Jan. 1914.

Of English parentage, George Cox was educated in the public and grammar schools of Colborne. He went to work there in 1856 as an operator for the Montreal Telegraph Company, which made him its Peterborough agent two years later. He also sold stationery, dabbled in photography, served as a travel and express agent, and in 1861 added an agency for the Canada Life Assurance Company, then based in Hamilton. Cox later said that on the day he became a Canada Life agent, he planned on becoming the company’s president.

As befitted an insurance salesman, Cox became a prominent citizen. Between 1872 and 1886 he served seven one-year terms as mayor of Peterborough, but he failed narrowly to be elected as a Liberal to the Ontario legislature in 1875 and to the dominion parliament in 1887. He was a devoted Methodist, contributing generously to local churches, working to build Methodist institutions, and campaigning vigorously for temperance during the Scott Act referendum of 1885 in Peterborough.

Cox built up his eastern Ontario branch of Canada Life until it was doing almost half the company’s business. As well, he was said to have a phenomenal eye for real estate. Gradually he accumulated large property holdings in the Peterborough area. In 1878 he became president of the fledgling Midland Railway, and he was instrumental in reorganizing, completing, and in 1883 leasing the system to the Grand Trunk. In 1880–81 he had been a member of the syndicate headed by Sir William Pearce Howland* that lost in a bid to win the charter for the transcontinental railway.

In 1884 Cox invested substantial profits from his railway ventures in founding the Central Canada Loan and Savings Company and several subsidiary mortgage loan operations in Peterborough. Two years later he was invited to join the board of directors of the Toronto-based Canadian Bank of Commerce. He invested heavily in the stock of both the bank and Canada Life.

Cox moved to Toronto in 1888, probably because of the convenience of handling his business network from the province’s main commercial centre, and possibly also because Scott Act supporters were distinctly unpopular in Peterborough. In 1890 he was elected president of the Bank of Commerce, which soon began a period of dynamic growth under the leadership of its brilliant general manager, Byron Edmund Walker*. Cox’s insurance agencies and mortgage loan companies were eventually managed by his three sons (Edward William, Frederick George, and Herbert Coplin) and his son-in-law Alfred Ernest Ames*. In 1889 Ames founded a stockbrokerage firm in Toronto; most of its business must have been trading for Cox, who guaranteed Ames’s credit at the Bank of Commerce.

A lifelong Liberal, Cox was one of the group that had bought the Toronto Globe in the 1880s [see Robert Jaffray], and also of the consortium that purchased and reorganized the Toronto Evening Star in 1899. He was presumably a major financial backer of the Liberal party, but records have not been found of what were probably large cash donations. In 1896 the newly elected government of Wilfrid Laurier appointed Cox to the Senate, where he was usually inactive. In 1903–4 his name was put forward by Laurier for a knighthood, but Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot] was cool to the proposal. “Cox I had always doubts about,” he wrote, “it was purely a political recommendation as a wealthy Govt. supporter.”

In Toronto Cox was a pillar of Sherbourne Street Methodist Church, which became known as the “Millionaires’ Church” because of the prominence of wealthy businessmen such as Cox, Ames, Harris Henry Fudger, Albert Edward Kemp*, and Joseph Wesley Flavelle*, an occasional Cox protégé who had also emigrated from Peterborough. For many years Cox was president of the Ontario Ladies’ College in Whitby, Ont., and bursar of Victoria College,the Methodist component of the University of Toronto. He continued to be an active temperance worker, and was a generous supporter of church organizations, the Toronto General Hospital, and other worthy causes.

During the early 1890s Cox moved to gain effective control of Canada Life. He accumulated all the shares he could and forced his way onto its board in 1892, at the cost of considerable resentment by other shareholders and directors. In 1899 Cox, who owned or controlled close to a 50 per cent interest, was instrumental in persuading the board to move Canada Life’s head office to Toronto, another step in the centralization of commercial and financial power in Ontario’s Queen City. Cox became president and general manager of Canada Life in 1900. As president of the Bank of Commerce and the Central Canada Savings and Loan in that year, he was the man at the centre of one of the country’s most important financial networks, controlling the placement of more than $70 million in assets.

The Cox companies formed an identifiable financial family, with intimately interlocking boards, routine and significant inter-firm transactions, and heavy reliance on a managerial/directorial group related to Cox by ties of blood, marriage, religion, or old home town. The network included two fire-insurance companies of which Cox was president, British America Assurance and Western Assurance, and it continued to expand with the founding of Imperial Life Assurance in 1897, National Trust in 1898, and Dominion Securities, a bond-trading company, in 1901. A number of the young men who got their start in Cox companies, such as William Thomas White*, Edward Rogers Wood*, James Henry Gundy*, and Edward Robert Peacock*, went on to outstanding careers in politics and finance. In 1898 Cox also briefly held a controlling interest in Manufacturers’ Life and the Temperance and General Life Assurance Company.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s the Cox companies seized a striking number of opportunities to invest the capital of their shareholders, policyholders, and depositors in new business ventures. In the early 1890s the Bank of Commerce and Cox had helped underwrite William Mackenzie*’s Toronto Railway Company, which electrified the city’s street-railway system. The Mackenzie connection led the Cox group into financing railways and street railways elsewhere in Canada and in the United States, the most spectacular being the Canadian Northern, the transcontinental line of Mackenzie and Donald Mann*.

The familiarity with electrical technology of Mackenzie and some of his associates, including Henry Mill Pellatt*, Frederic Nicholls*, and American engineer-promoter Frederick Stark Pearson, led to utility adventuring at home and abroad that was sometimes glitteringly successful. The Cox family’s promotion in 1900 of the São Paulo Tramway, Light and Power Company in Brazil, for example, became the basis of the set of enterprises that evolved by 1912 into Brazilian Traction, Light and Power. It became South America’s largest utility company and one of the most significant foreign investments by Canadians. The Cox group’s equally promising venture to bring power to Toronto from Niagara Falls through the Electrical Development Company, founded in 1903, was soon short-circuited by the competing movement for publicly owned low-cost electrical distribution.

In 1899–1900 the Cox companies advanced several prominent mergers and industrial promotions, including the Carter-Crume Company Limited, a manufacturer of sales-books, which evolved into the Moore Corporation, and the Canada Cycle and Motor Company, a merger of bicycle firms that, after some teething troubles, entered automobile manufacturing as well. Cox and several of his associates were active too in mining in British Columbia through the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company Limited, incorporated in 1897. From 1895 Cox had headed the syndicate that evolved into this company, of which he became president. His group’s connection with the Laurier government helped facilitate the Crowsnest Pass agreement with the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1897. Cox also served as a director of the transcontinental Grand Trunk Pacific Railway [see Charles Melville Hays] – even while the Bank of Commerce was backing the Canadian Northern – and of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited in Sydney, N.S. [see Benjamin Franklin Pearson]. In the first decade of the 20th century his list of directorships expanded to encompass 46 firms, great and small. Literally the landlord of the Toronto Stock Exchange, Cox was one of the two or three most powerful financiers in Edwardian Canada, a mobilizer and investor of capital, hence a pure capitalist.

Because he left few personal or business records, Cox’s character reveals itself dimly through a handful of terse letters and the recollections of some associates. Except for his church work, which seems to have involved more of his money than his time, he was single-mindedly devoted to his enterprises. He had no amusements or recreations, and read only newspapers and books about business. His associates marvelled at his grasp of business detail, his knack for figures, and his extraordinary self-possession. As a businessman he appears to have stressed the need to departmentalize large businesses to facilitate close accounting, and to have minimized risk by moving money into opportunities developed by members of proven capacity within his business family.

The public Cox was a close-mouthed man of affairs; the private Cox was said to be a simple, kindly man who supported many unlucky Peterboronians and others in need. Living in a handsome home in an older neighbourhood of Toronto, he chose not to participate in the burst of ostentatious mansion building that consumed the energies and fortunes of some of his younger associates.

Aside from occasional troubles brought on by dips in the business cycle, most of the Cox companies prospered handsomely during the Laurier years. Their business methods came under close scrutiny by the federal royal commission appointed in 1906 to investigate the Canadian life-insurance industry. Its proceedings revealed substantial cross-trading, subsidization, and other insider exchanges among Canada Life, Imperial Life, and other Cox family firms; some of these transactions were covert and/or technically illegal. The commissioners concluded, in their Report of 1907, that Cox’s absolute control of Canada Life had “to a marked extent influenced the investments of the company, which have been made to serve not only the interests of the Canada Life Assurance Company, but also his own interests. . . . In many of these transactions the conflict of Mr. Cox’s interest with his duty is so apparent that the care of the insurance funds could not always have been the sole consideration.”

Cox found the implication that he had abused situations in which he had multiple interests puzzling, largely because no one could prove that any of his transactions had failed to maximize the interests of policyholders or other investors in his companies. His defence of his conduct in the Senate in April 1907 was a classic apologia for unregulated capitalism, in which he particularly stressed the obvious personal integrity of the men who served on the boards of his firms.

In fact, a number of Cox’s associates were becoming increasingly anxious about the ageing financier’s determination to use Canada Life as a vehicle for the advancement of his personal family. They privately complained about the quality of Edward Cox’s work as general manager, about the covering up of Herbert’s incompetence, and about Cox Sr’s desire to increase his own salary. In 1911 Zebulon Aiton Lash, for many years the high-minded and brilliant lawyer to the Cox group, resigned from the board of Canada Life, along with Walker and two other directors, in protest against what Lash considered George Cox’s “glaring and objectionable . . . nepotism.” Flavelle, whose intimate business and church associations with the Cox family had begun in Peterborough in the 1860s, had left the board a few years earlier; he had concluded that “Mr. Cox does not possess the moral qualities which enable him to understand trustee relationships.”

Cox had relinquished the presidency of the Bank of Commerce in 1907, possibly as a result of concern about bad publicity from the life-insurance inquiry. After his death in 1914, the presidency of Canada Life subsequently passed to one son, then to another; eventually the firm was mutualized and the Cox influence disappeared. Although some of the interlocking relationships in the old Cox family of companies were maintained into the 1980s, many firms had grown, merged, failed, or otherwise drifted out of the system. There was never another godfather to knit a group together as tightly as George Cox had with the “Peterborough Methodist mafia.”

G. A. Cox became a millionaire in an age when a million dollars was still a fabulous sum. He had undoubtedly settled large amounts of money on his heirs before his death, so that his final estate of $870,000 would not be a true indicator of the real wealth he had accumulated. He first flourished supplying financial services, dealing in real estate, and promoting railways in a portion of central Ontario where the bounty of resources was creating a measure of general prosperity. His move to Toronto was part of the late-19th-century concentration of sophisticated financial services in that city. By 1900 he had become the wizard of finance at the centre of its most important web of banks, insurance companies, and investment firms. Cox and his associates then became instrumental in the spectacular maturing of the Canadian capital market; they perceived opportunities and developed techniques for funnelling the savings of Canadians, which had hitherto been concentrated in mortgages and bank and railway stock, into new opportunities in utility companies and industrials, sometimes located thousands of miles from Ontario.

The methods Cox used in his career of creative financial intermediation were not unusual for the era. The creation of families or networks of closely interrelated companies was standard practice in 19th-century business, particularly finance. Cox lived into and became somewhat discredited in a time of increased doubt that capitalists could be trusted to finesse their way, on moral character alone, through the conflicts inherent in so many forms of self-dealing. Ironically, the most serious distortions of his judgement arose because George Cox wanted to help out sons who had not inherited his own business ability.

[Business historians have been unable to locate any single collection of George Albertus Cox papers. The main primary sources for his biography are Cox correspondence and references to him in the Sir Joseph [W.] Flavelle papers at QUA; the Sir Byron Edmund Walker papers in the Univ. of Toronto Library’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Additional primary materials include Can., Senate Debates, the Canadian Bank of Commerce’s minutes for 1886–1907 (CIBC [Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce] Arch., Toronto, RG 14), the National Trust Company’s annual reports and minutes (National Victoria and Grey Trust Company Limited Library, Toronto), and the Monetary Times (Toronto), in particular the annual reports of Central Canada Loan and Savings Company. Good biographical entries were published during Cox’s lifetime in Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912); worthwhile obituaries include those in the Toronto Daily Star, 16 Jan. 1914, the Globe, 16–17 Jan. 1914, and the minutes of the Sherbourne Street Methodist Church’s board of trustees for 29 April 1914 (in UCC-C, Church records, Toronto Conference, filed with the records of St Luke’s United Church, Toronto).

For Cox’s particular affiliations, see G. W. Craw, The Peterborough story: our mayors, 1850–1951 (Peterborough, Ont., 1967); A. E. Ames & Co. Limited (privately issued pamphlet, Toronto, 1969; copy in the author’s possession); Since 1847: the Canada Life story . . . ([Toronto?, 1967?]); A. D. Morrow, “Memories of National Trust Ltd., 1898–1903” (an unpublished account in the National Victoria and Grey Library); and Michael Bliss, “Better and purer: the Peterborough Methodist mafia and the renaissance of Toronto,” in Toronto remembered: a celebration of the city, comp. William Kilbourn (Toronto, 1984), 194–205. Profiles of Cox appear in Augustus Bridle, “Hon. George A. Cox, financial sage,” Saturday Night, 11 Feb. 1911: 21, and in the author’s article “Getting on in life: the saga of George Cox,” Canadian Journal of Life Insurance (Elmira, Ont.), 1 (1978–79), no.5: 17–20, and his study A Canadian millionaire: the life and business times of Sir Joseph Flavelle, bart., 1858–1939 (Toronto, 1978).

The evolution of Canadian capital markets and the role of Cox’s companies are traced in Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, Southern exposure: Canadian promoters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1896–1930 (Toronto, 1988); Michael Bliss, Northern enterprise: five centuries of Canadian business (Toronto, 1987); I. M. Drummond, “Canadian life insurance companies and the capital market, 1890–1914,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 28 (1962): 204–24; R. B. Fleming, The railway king of Canada: Sir William Mackenzie, 1849–1923 (Vancouver, 1991); and Duncan McDowall, The Light: Brazilian Traction, Light and Power Company Limited, 1899–1945 (Toronto, 1988). m.b.]

Cite This Article

Michael Bliss, “COX, GEORGE ALBERTUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_george_albertus_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_george_albertus_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael Bliss |

| Title of Article: | COX, GEORGE ALBERTUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | September 25, 2025 |