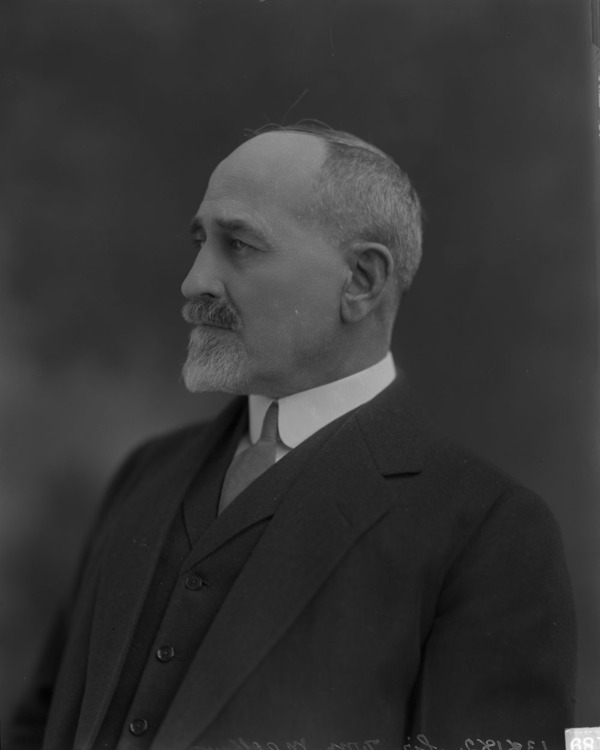

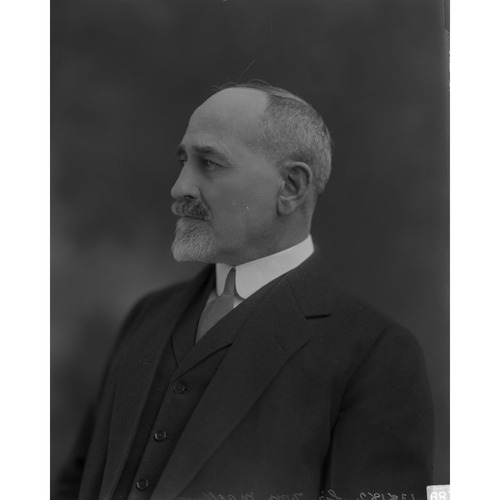

MACKENZIE, Sir WILLIAM, railway contractor and entrepreneur; b. 17 Oct. 1849 (he claimed 30 October) in Eldon Township, Upper Canada, fifth son of John Mackenzie, a farmer, and Mary McLauchlan; m. 8 July 1872 Margaret Merry (d. 1917) in Lindsay, Ont., and they had three sons and six daughters; d. 5 Dec. 1923 in Toronto and was buried near Kirkfield, Ont.

A son of Scottish-born Presbyterian immigrants, William Mackenzie was educated at elementary schools in Bolsover and Kirkfield, and at the Lindsay grammar school. After teaching for one or perhaps two years, he helped operate a small general store in Kirkfield for a short while. At about the time of his marriage in 1872 to Margaret Merry, a Roman Catholic, he joined his brothers’ contracting company. Beginning in 1874, he and Alexander, one of the brothers, obtained contracts to provide timber and to build bridges and other wooden structures for the Victoria Railway, a local colonization line being laid north from Lindsay. While working on it he became familiar with promoter George Laidlaw*, chief engineer and general manager James Ross*, and an ambitious young surveyor-office boy, Herbert Samuel Holt*. Mackenzie distinguished himself by completing his contracts on time and within estimate. He, Ross, and Holt then obtained work on another Laidlaw line in Ontario, the Credit Valley Railway. Mackenzie’s contracts, again for timber, bridges, and buildings, once more proved profitable. During return visits to Kirkfield the rising young builder forayed into local politics: he served as a councillor for Eldon Township (1876–77) and as reeve (1880–81).

Mackenzie’s situation changed after the dominion government signed a contract in October 1880 for a railway to the Pacific coast. Work began in 1881. Mackenzie visited western Canada for the first time the next year – like several other Ontarians he apparently hoped to obtain contracts on the new railway, but he failed to get any. James Jerome Hill*, the only member of the Canadian Pacific Railway syndicate with practical experience in construction, arranged the early contracts and he preferred large, financially stable American operators. By the end of the 1883 season, however, increased tensions between Hill and William Cornelius Van Horne*, the CPR’s general manager, together with financial and organizational problems, led to major changes in the company’s contracting procedures. James Ross was named manager of construction for the mountain section, and Herbert Holt became his superintendent. Ross and Holt divided the route into numerous small contracts and subcontracts, making it possible for contractors with limited backing to get work. This change, and the fact that Ross and Holt had worked with Mackenzie in Ontario, resulted in a series of contracts under which Mackenzie supplied timber and built bridges, stations, and other wooden structures for the CPR in 1884.

On his first contract Mackenzie demonstrated unusual financial talent. He did not have sufficient funds to purchase appropriate equipment. Instead, he returned to Eldon and scoured the countryside for available horses and other necessities; among his finds was an abandoned sawmill, which was dismantled and moved to Mackenzie’s work site in British Columbia. He gave little or nothing immediately, but promised payment in full after he was paid for his contract. The outfit he put together, not altogether suited to work in the mountains, was disdainfully referred to by other contractors as “The Farmer Outfit.” Most of the workmen were also recruited in Mackenzie’s home community and were sometimes dubbed the “Eldon reserve.” They too were prepared to wait for at least a portion of their wages. But they got the job done, earning Mackenzie a reputation as a contractor who completed work on time and within budget. It was during the 1884 season too that Mackenzie met his future partner, Donald Mann*, a bluff, masterful railway builder who held contracts for roadbeds. The following year Mackenzie was rewarded with a much larger project: to supply all the timber and erect a huge trestle bridge across the Mountain Creek gorge in the Beaver River valley in British Columbia. Designed by W. A. Doans, the bridge rose 150 feet and was 1,070 feet in length, reputedly one of the largest wooden trestles ever built.

Although the last spike was driven on 7 Nov. 1885, construction did not halt. Expedients had been adopted to make the official opening possible and most of the builders still had work to do on their contracts in 1886. Mackenzie also obtained new contracts, to construct heavy timber enclosures to protect sections of line in the mountains against snow slides. His projects kept him in British Columbia throughout most of the season. Ross, Holt, and Mann, who too had unfinished work, contracted as well in 1886 to build the first 40 miles between Winnipeg and Hudson Bay of a proposed railway (later renamed the Winnipeg Great Northern) that might serve as a CPR feeder and an alternative shipping route to overseas markets.

Subsequent projects eventually brought the four men together. In 1887 Mackenzie, Mann, and Holt all secured contracts on a new CPR project: the “Short Line” across Maine to Bangor, with an extension to Saint John. Mackenzie and Mann, who held adjacent contracts, decided in March 1887 to merge. Their work proved more difficult than anticipated and they would barely break even on their first venture as partners. In 1888 Ross obtained a general contract for the construction of the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan Railroad north from the CPR at Regina to Saskatoon and Prince Albert. Mackenzie, Mann, and Holt joined him in this undertaking. Even before it was finished, profitably and on time, the partners obtained another contract, for a line from the CPR at Calgary northward to Edmonton and southward to Fort Macleod. On both of these projects Ross was in charge, Mann did the clearing, brushing, and grading, Mackenzie handled the bridges and other wooden structures, and Holt laid the tracks. By 1888 Mackenzie was sufficiently well off that he built an impressive brick house in Kirkfield.

The foursome worked well together, but after 1890 there were no large construction contracts for steam railways in sight. There were, however, new opportunities to build urban railways utilizing new electrical technology. Mackenzie, Holt, and Ross all had considerable experience with various power systems, and they realized that the electrification of urban tramways offered new contracting and promotional opportunities. Mackenzie returned to Toronto, where he had already begun to branch out in 1889 as president of the Charles J. Smith coal and wood company. In 1891 he joined a syndicate which acquired control of Toronto’s horse-drawn trolley system, and obtained from that syndicate the construction contract for the electrification of the system. Ross and Holt became involved in the electrification of trams in Montreal, as did Mann in Winnipeg. (The four would often hold shares in each other’s street-railway companies.) Substantial sums were reputedly spent to bribe Toronto city officials and politicians so that Mackenzie’s group obtained a 30-year franchise for running the street railway. In April 1892 it was incorporated as the Toronto Railway Company, with interim financing from the Canadian Bank of Commerce, George Albertus Cox*, and others. Mackenzie, as contractor, received payment in cash to cover his costs. When the work was completed, he was given company shares for the balance due and he became president of the concern. He had gained control of the railway without investing much of his own money. The manner in which he had done so raised suspicions of corruption, while the building and operating tactics of the company provoked public anger. During construction, for instance, he had gained notoriety over the placement of hydroelectric poles and the tearing up and, it was claimed, inadequate repaving of roads. Once the system opened, Mackenzie and other officials became embroiled in a bitter debate in 1893, mainly with religious leaders, when the company decided to run cars on Sunday. Reduced ticket prices and easier transfer arrangements, however, earned it considerable goodwill.

The new electrical and traction technology was risky, but under Mackenzie’s leadership the Toronto Railway and affiliated electrical companies turned handsome profits. In 1896 Margaret Mackenzie bought land for a large summer home on Balsam Lake near Kirkfield and a year later William purchased Benvenuto, a mansion in Toronto. He fitted easily into Toronto’s early-20th-century nouveaux riches, and he and his wife became important patrons and collectors of Canadian landscape art. For him, and other promoters in the utilities field, success opened up further opportunities in Canada and abroad [see Frederick Stark Pearson*]. They developed technological, financial, promotional, and political expertise that took them not only to numerous other Canadian cities but also to Mexico, Brazil, the Caribbean, Britain, and even China. Mackenzie’s investment in street railways and utilities in Brazil in 1899 was the start of a major international venture. In Ontario, the franchise on Niagara Falls power secured in 1903 by the Electrical Development Company of Ontario Limited, controlled by Mackenzie, Frederic Thomas Nicholls, and Henry Mill Pellatt*, would make them key combatants against Adam Beck and other champions of a publicly owned system of distributing electricity.

In the 1890s unfinished business in western Canada had drawn Mackenzie into an even greater project, and his crowning achievement: the Canadian Northern Railway. The line from Winnipeg to Hudson Bay had encountered financial and political difficulties. Unpaid, Ross and Holt apparently lost interest but Mann hoped to salvage something from an adjoining line (the Lake Manitoba Railway and Canal, incorporated in 1889), which carried the promise of a federal land grant and a postal contract. He contacted Mackenzie, and together they devised a plan whereby the line would be deflected northwest to tap the rich agricultural area around Dauphin, Man. In 1895 they persuaded the Manitoba government of Thomas Greenway* to guarantee the bonds issued by the railway. With funds from their sale, loans from the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the hope of land subsidies and mail contracts, the private partnership of Mackenzie, Mann and Company built 125 miles of the LMRC in 1896. In December 1898 it and the Winnipeg Great Northern were amalgamated to form the Canadian Northern, with Nicholls as president; the new railway’s federal charter was obtained in July 1899.

The Canadian Northern differed in its construction and operation from other prairie railways. Mackenzie and Mann had agreed that, in return for a provincial guarantee of its bonds, they would reduce freight rates and submit their rate schedules for approval to the Manitoba government. They were confident that it would not impose unreasonable rates because the province would be liable if the railway could not pay interest and principal on the guaranteed bonds. The arrangement, however, demanded extreme economies. The region was only sparsely settled and would not generate much traffic in the early years. The railway was therefore built as cheaply as possible, albeit with a promise that it would be improved when there was more traffic. Most of the Canadian Northern’s early rolling stock was obsolete equipment obtained from the junkyards of wealthier American railways. Service was slow and breakdowns occurred often. But the Dauphin region finally had desperately needed rail service, which the CPR had been unwilling to provide. What really endeared the little railway to its patrons was the low rates it charged for freight.

The railway also initiated aggressive policies to increase the volume of traffic. It followed the example of the LMRC’s general manager, David Blythe Hanna*, who, when local farmers lacked good seed grain, had purchased several carloads and sold it to them at cost in 1897. There were similar responses to other shortages. On occasions when major suppliers refused to grant individual farmers volume discounts, the Canadian Northern bought the materials in sufficient volume to obtain the discounts and passed the savings on to the farmers. While the CPR accepted only grain shipped from elevators, the Canadian Northern was willing to allow farmers to load their grain directly into its cars, thus saving elevator charges. Other accommodations included unscheduled stops to pick up freight wherever it was offered. As a result, the railway came to be regarded as “the Farmers’ Friend” and was described as “the West’s own product to meet the West’s own needs.” What made its service even better was the fact that when Mackenzie and Mann lowered their rates, the CPR had little choice but to follow suit if it was to remain competitive and avoid even greater clamour for more government assistance for new Mackenzie and Mann lines.

In 1900 the American-based Northern Pacific, which had built lines in Manitoba, decided to sell them after years of poor returns. A proposed sale to the CPR, however, roused strong opposition and provided Mackenzie with an opportunity to make a daring counterproposal in 1901. The Canadian Northern was not in a financial position to purchase the lines, but Mackenzie suggested that the Manitoba government lease them and then reassign the lease to the Canadian Northern. In a much more significant move, he also promised drastic rate reductions on grain from Winnipeg to the Lakehead if the government would guarantee bonds to finance the construction of an extension over that stretch. Effective railway competition would thus be established from the prairies to the Lakehead, where water transport and then traffic exchanges with the Grand Trunk Railway would give the Canadian Northern access to eastern Canada. Through an assembly of charters that had actually begun in 1897, Mackenzie and Mann were able to complete a new line to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ont., by the end of 1901.

Mackenzie and Mann held the construction contracts for all the lines under the Canadian Northern umbrella. Their costs were paid from the proceeds of bond sales, and in lieu of profits they took Canadian Northern shares. In 1902 they incorporated their construction interests as Mackenzie, Mann and Company Limited. This move was intended to circumvent the provision in the Railway Act that prevented contractors on a railway from serving as its officers. The new company could henceforth acquire Canadian Northern contracts, and Mackenzie and Mann were both legally free to become officers. Consequently, in March 1902 Mackenzie became president of the Canadian Northern Railway, responsible for finances and with his headquarters in Toronto, where he lived. As vice-president, Mann would award construction contracts and deal with governments west of Ontario.

The success of their strategy depended on bond sales. To expand their system they acquired the charters of numerous small lines, some with valuable land subsidies and mail contracts; other railways were chartered provincially so they could receive the local government’s bond guarantees. Such backing facilitated sales, in which Mackenzie excelled. Although he could be domineering, he impressed colleagues, financiers, and politicians by his energy and assurance. He established close ties with leading Toronto financiers, particularly those associated with the Canadian Bank of Commerce, most notably Byron Edmund Walker, but his most important and difficult work involved the selling of bonds to British investors. He approached this task with the zeal of an itinerant evangelist, making numerous transatlantic crossings (often accompanied by one or more of his charming daughters). Assisted by Robert Montgomery Horne-Payne, a brilliant British financier, he not only made contact with leading underwriters in London but also went out into the countryside to sell bonds. Horne-Payne had the uncanny ability to assess how much money there was in a community for investment, which he and Mackenzie then systematically extracted. Both men had seemingly boundless faith in the future development of Canada, and the central role which the Canadian Northern could play in that development.

Mackenzie was a man of broad vision, not much interested in details. He was exceptionally fortunate in the legal services provided in Toronto by Zebulon Aiton Lash*, a former federal deputy minister of justice and a partner in Blake, Lash, and Cassels, one of Canada’s most prestigious law firms. Lash drew up the necessary contracts and documents, which provided excellent protection for Mackenzie and the Canadian Northern and in many cases introduced innovative features in corporate structuring. Lash made sure that the documents were filed and payments made on time – an important concern since the normal state of Mackenzie’s own office was chaotic, cluttered with piles of bills and other business, which Mackenzie was apt to ignore in the press of daily work. Mackenzie’s bargaining tactics often had a rough frontier-like quality, devoid of diplomacy. He would approve an agreement in principle and then look to Lash to put it into the appropriate language. Lash made sure too that the company’s financial records met legal requirements, although the overly optimistic accounts, with low figures for depreciation, may have prevented him, when combined with Mackenzie’s unbounded confidence, from recognizing the warning signals that Canada’s economic boom might be coming to an end.

Contrary to early predictions, the prairie lines built by Mackenzie and Mann had operated at a profit from the beginning. The main reason for their success was the tremendous increase in immigration and settlement and hence in the volume of rail traffic in western Canada. This growth allowed Mackenzie and Mann to improve substantially their main lines and to build many new branches – theirs was the railway of the northern prairies. They understood the needs and interests of prairie farmers, adapted operations to local circumstances, and set freight rates at levels that earned them much goodwill. In recognition of their contribution to the development of western Canada, they would both be knighted on 1 Jan. 1911.

It is not clear when William Mackenzie and Donald Mann made the transition from western contractors to national entrepreneurs. Before 1901 it was widely believed that they were simply building urban street railways and prairie lines with the intention of selling them at a profit to the CPR or another prospective transcontinental. The presence on the Toronto Railway board of W. C. Van Horne, now the CPR’s president, and the employment of his son on Canadian Northern construction projects lent credence to allegations, by Northern Pacific officials among others, that Mackenzie and Mann were merely a front for the CPR. They seemed to acquire charters and build lines in an uncoordinated way.

Associates later regarded the 1901 agreement with the Manitoba government as the turning point when Mackenzie and Mann first entertained ambitions to build their own transcontinental. Others have suggested that the turn happened only in 1903 when the Grand Trunk decided to move into western Canada and tried to take over the Canadian Northern, but was rebuffed. The federal government had agreed to assist the Grand Trunk Pacific, headed by Charles Melville Hays*, but this support softened when it became clear that the Grand Trunk would not retain the low Canadian Northern rates on grain moving to the Lakehead. At the same time, Mackenzie and Mann’s resistance to Grand Trunk incursion was significantly strengthened by cabinet’s promise, facilitated by Clifford Sifton, to guarantee Canadian Northern lines to Edmonton and Prince Albert.

Mackenzie and other senior Canadian Northern officials later insisted that the Grand Trunk’s move westward made the transcontinental expansion of the Canadian Northern inevitable if it was to remain competitive. They had recognized that eastern connections had to be secured when they became available, a process that started in earnest with the acquisition in 1903 of the Great Northern Railway, which gave them vital access to a system across Quebec. Mackenzie and Mann moved closer to their transcontinental goal in 1909 when the government of British Columbia provided bond guarantees for the building of a Canadian Northern subsidiary from Alberta to Vancouver. At the same time Saskatchewan and Alberta, for the first time, offered guarantees to facilitate construction of a network of new branches. Mackenzie and Mann had also obtained charters, and in some cases government assistance, to build railways that served local needs, but were also situated to become parts of a transcontinental system.

In Mackenzie’s bold surge as a national entrepreneur, a succession of major business deals kept pace with railway assembly. Ventures in Pacific whaling, insurance, lumber, ore mining, meat packing, brewing, retailing, and foreign utilities, among others, consolidated the position of Mackenzie, Mann as a pre-eminent Canadian holding company. Other initiatives were clearly linked to the Canadian Northern’s expansion, such as Mackenzie and Mann’s acquisition in 1910 of the Brazeau coalfields in Alberta and the coal operations of James Dunsmuir* on Vancouver Island. In Britain that year to launch the service of the Canadian Northern Steamship Company, the masterful Mackenzie, at the peak of his influence, secured financing worth an extraordinary $40,700,000, much of it destined for railway construction.

The final link in his transcontinental system fell into place only in 1911, when the embattled federal Liberals, fighting an election on a proposed reciprocity treaty with the United States which critics argued would divert much Canadian trade southward, tried in May to demonstrate their commitment to east–west trade by guaranteeing a proposed Canadian Northern line north of Lake Superior. The results, however, would be tragic for the two new transcontinentals: the Canadian Northern was unable to establish an adequate traffic base in eastern Canada while the Grand Trunk Pacific failed to do so in the west.

Shortly after the federal guarantee, Mackenzie and Mann began to encounter serious financial problems. In 1912 a crisis in the financial markets, triggered in part by fears of a European war, made it more difficult and expensive to sell the railway’s bonds. The crisis came just as the Canadian Northern was facing costly construction in the Rockies and north of Superior. At the same time restrictions on emigration by European governments sharply reduced settlement in western Canada. Then, following the outbreak of war in 1914, the availability of rolling stock, supplies, and workers became problematic. Mackenzie and Mann tried to reduce costs, but they were determined to complete, open, and equip the Canadian Northern’s transcontinental line. The last spike was driven by Mackenzie in an unofficial ceremony at Basque, B.C., on 23 Jan. 1915; the final mileage had been hastily thrown together in a desperate effort to give the railway greater credibility. Much additional construction remained to be done that year, and it was only in late August that a train carrying a small party including railway and bank officials made what amounted to the inaugural trip from Toronto to Vancouver. Two months later a special excursion train, hosted by Mackenzie, took a large press corps, politicians, businessmen, and other dignitaries from Quebec City to Vancouver. The celebrations were lavish, but they could not mask a harsh reality. The Canadian Northern could not survive the war without massive government assistance, which federal politicians found almost impossible to justify in the face of more urgent wartime needs. The government of Sir Robert Laird Borden* provided interim aid [see John Dowsley Reid] and then in 1916 set up a royal commission to recommend long-term solutions to the country’s railway problems. In the end Ottawa decided to take over and merge the two financially embarrassed transcontinentals.

A devastated Mackenzie fought hard to maintain control of the Canadian Northern, his largest and most cherished venture, but on 1 Oct. 1917 the Union government, Mackenzie, Mann and Company Limited, and the Canadian Bank of Commerce signed an agreement whereby the government would acquire the Canadian Northern common shares in private hands. The price for the shares, almost all of which were held by Mackenzie and Mann, would be arbitrated. The amount awarded by the board of arbitration in its report of 25 May 1918 ($10,800,000) was barely sufficient to discharge their indebtedness to the bank.

Mackenzie remained active in numerous business operations even after the loss of the Canadian Northern. International financial hardships following the war depressed the value of his stock in Canadian and Latin American electrical and traction companies and of the many lumber, coal, real estate, mining, manufacturing, insurance, and financial operations in which he was interested. In 1920–21 he gave up his hydroelectric interests and his street railways in the Toronto area. Though he was able to maintain an affluent lifestyle at Benvenuto and at the family’s homes in the Kirkfield area, the complicated estate he left at his death was, for a one-time magnate, relatively modest.

Sir William Mackenzie suffered an apparent heart attack in October 1923 and he died on 5 December. In life he had been one of Canada’s most colourful and controversial railway promoters and entrepreneurs. In the opinion of Sir Edmund Walker, the banker with whom he had many dealings, he seemed “like the railway, driven by a steam engine.” Mackenzie was, perhaps, too optimistic in his assessment of the economic prospects of Canada, particularly western Canada. His rapid rise to wealth and fame had the appearance of a meteor blazing a bright trail through the skies of the Canadian business world, but this meteor had burned itself out several years before Mackenzie’s body was committed to the earth near his home town of Kirkfield.

[The primary sources for Sir William Mackenzie and the Canadian Northern are given in the author’s study The Canadian Northern Railway, pioneer road of the northern prairies, 1895–1918 (Toronto, 1976). Mackenzie left virtually no private papers, a paucity that is admirably compensated for in R. B. Fleming, The railway king of Canada: Sir William Mackenzie, 1849–1923 (Vancouver, 1991). Obituary notices appear in the Canadian Railway and Marine World (Toronto) and in several Toronto and Montreal newspapers. Other useful works include Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, Monopoly’s moment: the organization and regulation of Canadian utilities, 1830–1930 (Philadelphia, 1986), and Southern exposure: Canadian promoters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1896–1930 (Toronto, 1988); Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912); Encyclopaedia of Canadian biography . . . ; Duncan McDowall, The Light: Brazilian Traction, Light and Power Company Limited, 1899–1945 (Toronto, 1988); Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell); and G. R. Stevens, Canadian National Railways (2v., Toronto and Vancouver, 1960–62), 2. t. d. r.]

Cite This Article

Theodore D. Regehr, “MACKENZIE, Sir WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_william_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mackenzie_william_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Theodore D. Regehr |

| Title of Article: | MACKENZIE, Sir WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 13, 2026 |