Source: Link

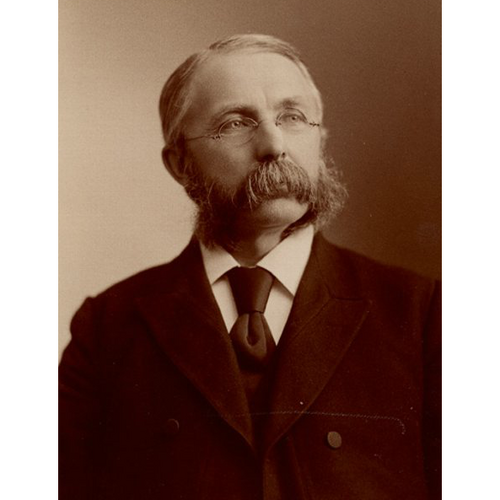

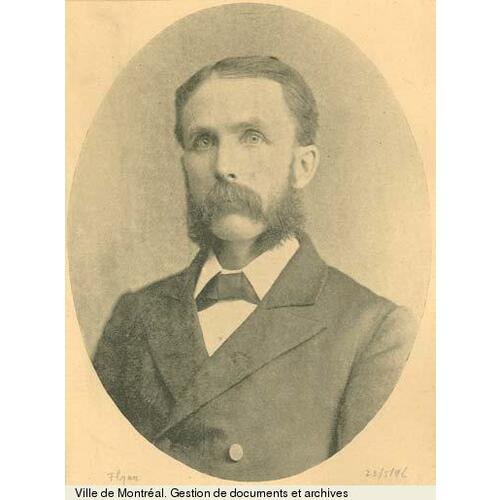

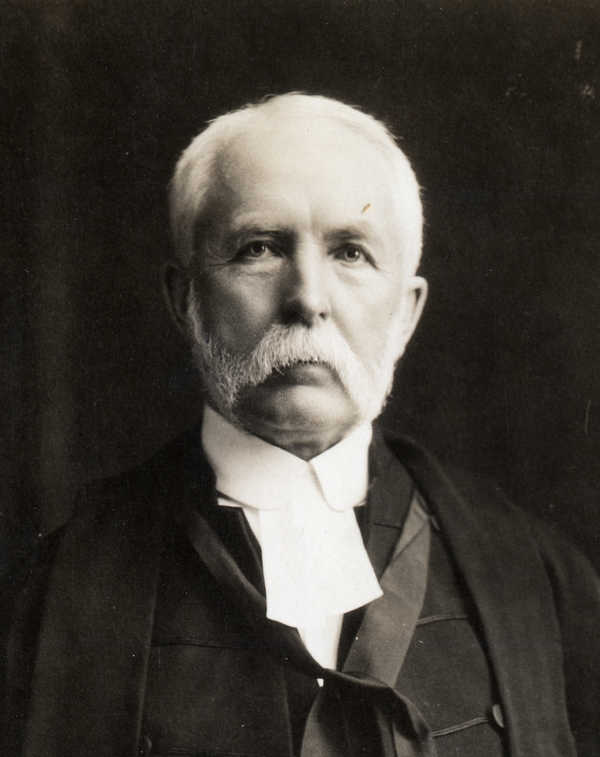

FLYNN, EDMUND JAMES, lawyer, professor, politician, and judge; b. 16 Nov. 1847 in Percé, Lower Canada, son of James Flynn, a fisherman, and Elizabeth Tostevin; m. first 11 May 1875, at Quebec, Augustine Côté (d. 1911), daughter of Augustin Côté*, publisher and owner of Le Journal de Québec, and they had 11 children, four of whom survived him; m. secondly 8 Jan. 1912 Marie-Cécile Pouliot, widow of Eugène Globensky, in Montreal; d. 7 June 1927 at Quebec and was buried in Notre-Dame de Belmont cemetery at Sainte-Foy, Que.

The Flynns, who had settled at Percé in the Gaspé region, were of Irish descent. Edmund James Flynn’s paternal grandfather, Edmund, was born in Percé, where he managed a large commercial firm and was a customs officer. On his mother’s side, his grandfather, John, was from Guernsey and his grandmother from Jersey. His father made his living from business, fishing, and farming. His mother was also born in Percé.

Bilingual and Roman Catholic, Edmund James studied at the Séminaire de Québec from 1860 to 1865. From 1867 to 1869 he had his initiation into administration as assistant registrar, assistant prothonotary, and assistant clerk to the Court of Queen’s Bench, registrar of the Circuit Court for the District of Gaspé, and secretary-treasurer of the municipality of Percé. He studied law at the Université Laval in Quebec City from 1871 to 1873, obtaining his degree with distinction. On 16 Sept. 1873 he was called to the bar of the province of Quebec and he took up his profession in the region where he was born. The following year he moved to Quebec, where he was to live from then on. He would practise law there until 1914 in partnership with Édouard Rémillard, François-Xavier Drouin, and Jean Gosselin, and then with his son Francis. He would be bâtonnier of the Quebec bar from 1907 to 1909.

From the time he arrived in Quebec, Flynn taught a course in Roman law at the Université Laval, where he was to obtain a doctorate in law in 1878 at the age of 31. He would have a long career there as professor of Roman law until his death, member of the university council from 1891 to 1927, as well as dean of the law faculty and member of the board of governors from 1915 to 1921.

Flynn became interested in politics early in life. In 1874 he was the Liberal candidate for the riding of Gaspé in the federal general election, but because he was appointed at the same time to the faculty of the Université Laval he withdrew from the race. He ran again as a Liberal in Gaspé in 1875, this time in a provincial general election, but he was defeated by Dr Pierre-Étienne Fortin*. The following year Flynn accused him of having benefited from clerical interference. Once exonerated, Fortin bested him again in the by-election that was called for 2 July 1877, after the previous election was declared null and void.

On 1 May 1878 Flynn finally gained a seat, by acclamation, as the Liberal member for Gaspé in the Legislative Assembly. In this general election, his party under Henri-Gustave Joly* came to power, but both Liberals and Conservatives had the same number of seats in the house. The leader of the opposition, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, made offers to some of the Liberal members to persuade them to abandon Joly and shift the balance of the house to the Conservatives. Flynn probably received a specific proposal from Chapleau. On 29 Oct. 1879 he and four of his Liberal colleagues voted for a motion by William Warren Lynch* calling for the establishment of a coalition government. He thereby stood against his party, which was seeking instead to abolish the Legislative Council. By joining the ranks of the Conservative party, these members reduced the Joly government to a minority and it had to resign.

The new premier, Chapleau, paid his debts and gave the renegade from Gaspé the portfolio of crown lands. After a mere year and a half in the Legislative Assembly, Flynn had become a commissioner. Meticulous, honest, and conscientious, he got down to work under the watchful eyes of the Liberals, who tried to embarrass this traitor in the house, especially on the question of the Legislative Council.

When Chapleau resigned as premier in 1882 to move into federal politics, his successor, Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*, did not include Flynn in his cabinet. His time in purgatory did not last long, because Mousseau was replaced in January 1884 by John Jones Ross*, who invited Flynn, a moderate conservative, to become commissioner of railways (1884–86) and then solicitor general (1885–87). In the house in 1886 Flynn had to confront such tough adversaries as Honoré Mercier*, when, in the absence of Ross, he had to defend the provincial government’s refusal to censure the federal government’s stance in the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*].

Early in 1887, Mercier’s Parti National came to power on a groundswell of public opinion related to the Riel affair, and Mercier replaced Louis-Olivier Taillon, who had just succeeded Ross. For the first time Flynn found himself in opposition. Then, in the provincial general election of 1890, in which Mercier was again victorious, he lost the seat he had won as a Conservative in 1879, 1881, 1884, and 1886. He ran in the riding of Quebec in the federal general election of 1891, but was again defeated. During the period when he was out of the house, Flynn devoted himself exclusively to his law practice and university teaching.

Dismissed as premier by Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers* following the Baie des Chaleurs Railway scandal, Mercier had to relinquish power on 16 Dec. 1891 to the Conservatives under Charles Boucher* de Boucherville. Within a few days Flynn became commissioner of crown lands again. In the provincial general election of 8 March 1892, taking no chances he ran in two ridings, Gaspé and Matane, as the law allowed. Elected in both, he opted for Gaspé and retained his office as commissioner. At the end of 1892 he was also acting attorney general. An enlightened, efficient man capable of big ideas, in 1895 he revised the mining act, which he had put through in 1880, settled the old question of property titles on the Îles de la Madeleine, and created the Parc National des Laurentides and the Parc de la Montagne Tremblante.

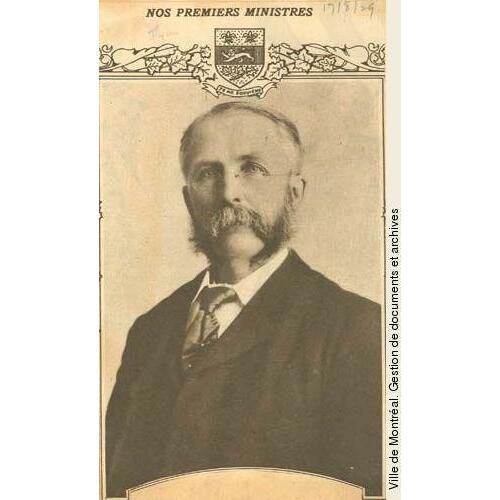

At the beginning of May 1896, Taillon, who had succeeded Boucherville as premier a few years earlier, went to Ottawa to become postmaster general. Since his appointment had been made quickly, Taillon wrote to Lieutenant Governor Chapleau on 4 May that “it is hardly appropriate for me to offer you my opinion on the choice of my successor.” Chapleau wanted to offer the office to a member of the moderate wing of the Conservative party, represented by Guillaume-Alphonse Nantel* and Flynn, rather than to a cabinet member connected to its ultramontane or Castor wing. Since Chapleau ruled out the Castors and they ruled out Nantel, Flynn, who was the senior member of the cabinet and against whom no personal objections were raised, was a good compromise. The lieutenant governor made a symbolic offer to Nantel, who refused to form a new cabinet. Thus on 11 May 1896 Flynn became the tenth premier of the province of Quebec. In his cabinet, within which Thomas Chapais* and Louis-Philippe Pelletier were the strongest members, he kept the portfolio of public works for himself. However, the team would have to function without two party stalwarts, Taillon and Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, who would soon follow Taillon to Ottawa.

Flynn’s agenda, which was less austere than Taillon’s but more cautious than Mercier’s, included conversion of the public debt (through replacement of the bonds in circulation by longer term bonds at a lower rate of interest), higher railway subsidies, reorganization of government departments, more rational development of natural resources, and abolition of the property transfer tax that had been imposed in 1892. The premier, who had in addition been leader of the Conservatives since 13 June, turned his attention to matters related to primary education, in particular financial assistance to poor municipalities and an increase in teachers’ salaries. Debt conversion and railway subsidies were the most debated subjects in the house. Conversely, the legislation known as the Homesteads Act, intended to protect settlers against the seizure of essential property (200 acres of land, house, livestock, farm implements, household equipment), was favourably received.

The Conservatives’ term of office was coming to an end, however, and it was time to think about an election. Polling day was set for 11 May 1897. Within only a year of his appointment as premier, Flynn had already accomplished a great deal. During that same period of time, two of his daughters had died of some form of tuberculosis; two others would fall victim to the same disease, one in 1898 and the other in 1906. The Conservative leader was faced with a very unfavourable situation, due, among other things, to the normal wear and tear of being in power, the Liberals’ arrival in strength in Ottawa under Wilfrid Laurier*, the strong resentment against the Conservatives because of their decisions on the Manitoba schools question [see Thomas Greenway*] and the Riel affair, as well as the rehabilitation of Mercier, who had died in October 1894. Pelletier, who served as attorney general in Flynn’s cabinet, wrote to him on 17 Nov. 1896, “I do not think we can win the election starting as we are at this moment. . . . We have cut costs, we have healed the wounds inflicted on the province: this is good, but it is not enough.” Furthermore, the incumbent premier was not well known (especially in Montreal), and with his rather reserved and lacklustre personality he was not an orator who could stir up crowds.

The political agenda Flynn put forward during the campaign was a continuation of his achievements of the previous year. He asked to be judged on his program and its results, and for federal issues to be kept out of the provincial election. The Conservatives mounted a furious attack on the Mercier government, which was still being blamed for all existing ills. As for the Liberal leader, Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, he concentrated mainly on the Conservative government’s record and its poor financial management. Laurier’s organizers also arrived in strength and the election campaign soon took on the appearance of a confrontation between Flynn and Laurier. On polling day, Marchand’s Liberals won an easy victory, taking 52 seats. The Conservative leader, one of the 22 candidates elected for his party, kept his seat in Gaspé, but by a margin of only 11 votes. With the fall of Flynn’s cabinet, the last Conservative government in Quebec disappeared and the party was not to regain power in the province. The Union Nationale, which would win the 1936 election, would emerge from a coalition of the Conservative party and the Action Libérale Nationale.

Flynn now became the inconspicuous leader of a demoralized opposition. The country was enjoying a notable period of economic prosperity and both the federal Liberals and their provincial counterparts had everything going in their favour. The latter called an early general election for 7 Dec. 1900 and again swept the province with no difficulty. During the campaign, Flynn made a half-hearted and largely unsuccessful attempt to denounce federal interference in provincial politics. (A few months earlier, Marchand’s death had made it necessary for a new premier to be appointed, and it was reportedly Laurier who had decided in favour of Simon-Napoléon Parent*.) Rather than risk running in Gaspé, Flynn chose the riding of Nicolet, where his party had won every election since 1867, with the exception of 1890. He took the seat with a majority of 41 votes.

On 3 Nov. 1904 Laurier was returned to power in the federal election. The next day, while Flynn was still leader of the opposition in Quebec, Parent had the Legislative Assembly dissolved and set 25 November as the day to go to the polls, thereby forcing the voters to make up their minds in record time. Since the Liberals had carried 64 of 74 ridings in 1900, all they had to do was nominate the same members. Flynn was not in the same situation and had little time to get ready. He signed a manifesto denouncing Parent’s actions and accusing him of trying to identify his candidature with Laurier’s. The opposition would not play that game, he declared. He then ordered his followers to challenge the legitimacy of the election (which he described as a power grab) by abstaining from it. He himself did not run. The directive was not universally followed, and again the Liberals won an easy victory. The following year, having no seat, Flynn resigned as leader of the Conservative party, which by then had only one daily paper, L’Événement, and just seven members in the house.

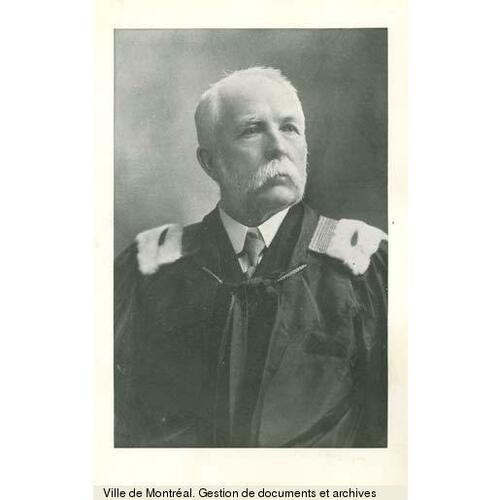

After some 30 years in politics, Flynn now had to resume a professional life with a lower profile – his law practice and university teaching. In 1908 he made a final, unsuccessful bid to return to the political scene by running in Dorchester in the federal general election. He brought his son Francis, recently called to the bar, into partnership with him in 1911. Then came more bereavements. His wife Augustine died that year after a brief illness and in June 1919 Francis died of pulmonary tuberculosis. Flynn had been appointed a judge of the Superior Court for the district of Beauce in June 1914. In June 1920 he became a judge of the Court of King’s Bench, an office he held for the rest of his life.

More at home in court or in the classroom than on a political platform, Edmund James Flynn was a conscientious politician known for his attention to detail, his thorough grasp of the issues, and his masterful and careful reasoning. This professor of law carried out some very worthwhile legislative work, especially in the Department of Crown Lands. Eloquent, skilful, and convincing as a speaker, he was especially at ease with constitutional questions. He showed sound judgement; his caution often, indeed, made him hesitate before taking action. But his political instinct, his sensitivity to the moods of the electorate, his vision of the major social issues, as well as his fighting spirit, all came to naught. With his lacklustre, unassuming, and phlegmatic (one might even say austere) personality, this transitional politician, who never learned how to make small talk, became premier of Quebec at the wrong time. Flynn could not compete with such charismatic personalities as Laurier, Joseph-Israël Tarte*, or even Marchand.

No biography of Edmund James Flynn exists. The main archival source for his life is a modest collection in ANQ-Q, P734, S1, consisting of correspondence, telegrams, speeches, documents relating to governmental and legislative affairs, and addresses to electors, as well as personal and family information. Additional material is in LAC, MG 27, II, F8. Flynn’s speeches are collected in various pamphlets. The Debates of the Legislative Assembly of the province of Quebec, 1878–1904, constitute an important source for his political career, particularly those for the sixth session of the eighth legislature (1896–97).

ANQ-BSLGIM, CE102-S19, 18 nov. 1847. ANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 11 mai 1875. BCM-G, RBMS, Saint-Jacques-le-Mineur (Montréal), 8 janv. 1912. L’Action catholique (Québec), 7 juin 1927. Le Devoir, 7 juin 1927. L’Événement, 8 juin 1927. Le Soleil, 7 juin 1927. Ken Annett, “To clutch the golden keys: the distinguished career of Edmund James Flynn,” SPEC (New Carlisle, Que.), 10 (1984), no.42: 14. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Marc Desjardins et al., Histoire de la Gaspésie (nouv. éd., Sainte-Foy, Qué., 1999). DPQ. Jacques Flynn, Un bleu du Québec à Ottawa (Sillery, Qué., 1998). J.-A. Lamarche, Les 27 premiers ministres (Montréal, 1997). Laurent Laplante, “Edmund-James Flynn,” in “Portraits des premiers ministres du Québec” (Radio-Canada broadcast, Montreal, 1982; copy in BCM-G). Où sont les cliquards: le groupe Flynn, ce qu’il en coûte à la province ([Québec?, 1897?]). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.8–9, 12. George Stewart, “The premiers of Quebec since 1867,” Canadian Magazine, 8 (November 1896–April 1897): 289–98.

Cite This Article

MARC DESJARDINS, “FLYNN, EDMUND JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 28, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/flynn_edmund_james_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/flynn_edmund_james_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | MARC DESJARDINS |

| Title of Article: | FLYNN, EDMUND JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 28, 2026 |