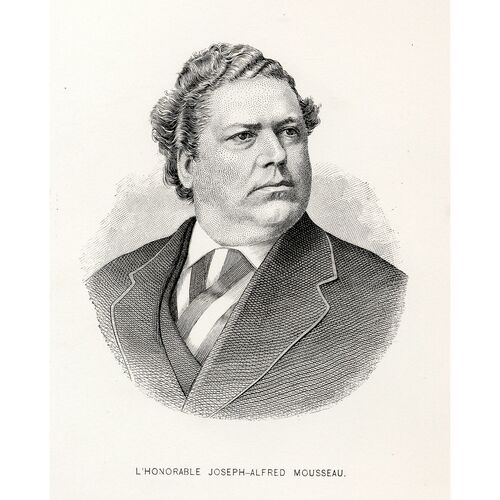

MOUSSEAU, JOSEPH-ALFRED, lawyer, journalist, writer, politician, and judge; b. 18 July 1838 at Berthier-en-Haut (Berthierville), Lower Canada, son of Louis Mousseau and Sophie Duteau, dit Grandpré; m. there on 20 Aug. 1862 Hersélie Desrosiers, and they had 11 children; d. 30 March 1886 in Montreal, Que.

Joseph-Alfred Mousseau’s family must have immigrated to Canada by the 17th century, since Jacques Mousseaux, dit Laviolette, whose parents came from Azay-le-Rideau, near Tours, France, married Marguerite Sauriot (or Sauviot) on 16 Sept. 1658, at Ville-Marie (Montreal). Joseph-Alfred attended the Académie de Berthier but, according to his contemporaries, he was largely self-educated. He came to Montreal to study law and worked there under Louis-Auguste Olivier, Thomas Kennedy Ramsay, Lewis Thomas Drummond, and Louis Bélanger. He was called to the bar in 1860 and appointed a qc in 1873. For 20 years he practised both civil and criminal law with the legal firm of Mousseau, Chapleau et Archambault, which became Mousseau et Archambault when Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* left. Noting that he was a fiend for work, his friend Laurent-Olivier David* observed: “He had a good mind, possessing sound judgement, a splendid memory and a lively imagination. He was above all a worker, a plodder, who spent his nights studying, consulting sources, preparing his speeches or his writing. Often, after arguing in court all day, he would set to work again at eight o’clock in the evening, and continue until three or four in the morning. He kept himself awake by taking ten or more cups of coffee and frequently other stimulants. A disastrous habit.”

While engaged in legal practice, Mousseau was also active as a journalist and writer. On 2 Jan. 1862 a new paper, Le Colonisateur, began publication in Montreal as the successor to La Guêpe, started by Cyrille Boucher* and Adolphe Ouimet. The journal’s goal was to assist settlement in the province. Mousseau was one of its proprietors, along with Ludger Labelle*, Chapleau, Louis-Wilfrid Sicotte, and David. In this group were adherents of both political parties. These young intellectuals set out to cut across party lines and to carry out the patriotic project of fostering settlement in the province. They wanted to provide the public with the information essential for the success of the colonizing venture. Because agriculture was closely linked to settlement, in the article of 2 Jan. 1862 outlining their intentions they also committed themselves to the improvement of “that art” on which “the prosperity of a country” depends. In order to survive Le Colonisateur had to attract as many readers as possible. It therefore opened its columns not only to subjects related to settlement, such as political economy, industry, and commerce, but also to literature and science. Mousseau’s contributions were anonymous, like all the other articles, for the journal was put together on a committee basis. But it is known that he contributed for only a short period since the final issue of the paper was published on 27 June 1863 and by then David and André-Napoléon Montpetit had been its sole editors for some months. It is easy to understand why such a specialized journal would not last long. During its run it gave extensive coverage to the report of Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau* on settlement, which had been published at the end of 1861, advocated bold measures such as the creation of a ministry of colonization and of an agricultural bank granting loans on landed property, called on the public to support the building of chapels in the “settlements” because the latter had always prospered “when they had missionaries in charge,” publicized the places “most suitable for settlement” and the government policies favouring it, and stressed new measures relating to immigration, repatriation, and settlement. Le Colonisateur, in fact, virtually exhausted the topic. It was already at a low point when in December 1862 a rival, Le Défricheur, was launched at L’Avenir by Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion*, the former general manager of the paper L’Avenir, and it ground to a final halt on 27 June 1863.

Seven years later Mousseau embarked on another newspaper venture. In 1870, with David and George-Édouard Desbarats*, he founded L’Opinion publique at Montreal. This weekly had some novel features: a new engraving process, “leggotype” (a variation of lithography), was used to attain an unprecedented quality of reproduction; the articles were written carefully, indeed with some literary pretensions, and were all signed; the publication had no definite political orientation, which according to David “makes composing it stimulating and pleases both parties.” L’Opinion publique was successful and profitable for a while. After two years the circulation reached the unusual figure of 12,000 to 13,000, but in 1873, at the time of the Pacific Scandal, the paper was undermined by internal divisions. Scanning it, one becomes aware that Mousseau contributed regularly for three years, signing the column on international politics. It is also evident that he had literary and scientific interests, and that he was becoming increasingly sensitive to domestic politics; indeed he took pleasure in pointing out that while L’Opinion publique had not made him rich it had given him access to Bagot County. It is to be noted that Mousseau was in tune with the spirit of the periodical and, contrary to the trend of 19th-century journalism, had nothing of the polemicist who wields the pen as if it were a sword.

Mousseau also wrote two literary pieces. The first was a Lecture publique . . . sur Cardinal et Duquet, victimes de 1837–38, prononcée lors du 2e anniversaire de la fondation de l’Institut canadien-français, le 16 mai 1860. In it he described the lives and characters of Joseph-Narcisse Cardinal* and Joseph Duquet*, who having refused to join the insurgents in 1837 took part in the rebellion of 1838 because they counted then on the general cooperation of the population, the forces in the two Canadas, and the help of the Americans. Beyond these two “martyrs of nationality and liberty,” Mousseau wanted to extol all those “who have loved their country and their nationality.” The list of those he admired included Elzéar Bédard*, Louis Bourdages*, and Joseph Papineau*, but not the leader of the rebellion, Louis-Joseph Papineau*.

Mousseau’s second work, Contre-poison: la Confédération c’est le salut du Bas-Canada; il faut se défier des ennemis de la Confédération, published on 25 July 1867, is better known. Writing with the interests of the Conservative party in view, the author replied to the pamphlet in which Dorion had declared himself, in the name of the Rouges, against confederation. A plea in support of the “great and splendid” confederation, “the worthy consummation of such a splendid past which definitively establishes the French-Canadian nationality, creates a great nation, and gives the country a solid and lasting foundation,” Mousseau’s pamphlet was also a condemnation of the party of “the ungodly, the annexationists and the ex-agents of the secret societies” who refused to accept confederation. Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe summed up its significance in three concise statements: “It abounds in information; its style is extremely vigorous. All voters should have a copy.”

Mousseau’s zeal in defending Conservative interests at the time of confederation was an indication that he might enter politics, and that zeal would again be seen during the Pacific Scandal. In the federal election campaign of 1872 he, with Chapleau, Clément-Arthur Dansereau*, and others, had a great influence on the youth of Montreal, who were becoming completely unresponsive to the scheming, manipulative tactics to which Sir George-Étienne Cartier* and the old hands of the party still clung, failing to realize that the party was thereby slipping from their control. The progressive thinking of these young conservative lawyers might have set back the emerging nationalist party which brought together both Liberals and Conservatives. But Mousseau was not content to have only an ideological influence; clearly he wanted to jump into the political arena. In January 1874, when the abolition of the double mandate opened the way for newcomers, he ran in the federal election in Bagot where the seat had been left vacant when Pierre-Samuel Gendron chose the provincial one. Since the Conservative party was in a shaky position as a result of the Pacific Scandal, Mousseau tried to secure the support of some of the moderate Liberals. He promised to give free play to Alexander Mackenzie*’s new ministry and to judge it solely on its political performance. Probably as a result of these tactics he beat his opponent Jean-Baptiste Bourgeois, the former “Danton” of the Parti National, by 43 votes.

During the first phase of his political career Mousseau sat with the opposition. He made a good impression, although his role was necessarily a minor one. When they had relinquished office, the Conservatives had left pending such important questions as the creation of the Supreme Court of Canada, a general amnesty in the northwest, and the New Brunswick separate schools. These issues prompted the French Canadians to adopt a nationalist standpoint. It was this stance that characterized Mousseau’s political actions in the house, where it associated him with the Parti National group to which Louis-Amable Jetté*, David, and Honoré Mercier* belonged.

One of Mousseau’s first moves in parliament was to support Liberal Henri-Thomas Taschereau’s attempt to limit the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Canada to cases coming under federal law. Taschereau felt that it would be unjust for judges who were mostly strangers to the province of Quebec and its Code civil to be able to reverse decisions of Quebec judges; his amendment was rejected by 118 to 40. Mousseau expected to see the Quebec Liberals split with the government on this issue, but party discipline prevailed over his colleagues’ nationalism.

On 12 Feb. 1875 Mousseau put forward an amendment to Mackenzie’s resolution concerning a general amnesty for those involved in the 1869–70 disturbances in the northwest. He made a five-hour speech proposing that the three exceptions stated in the resolution be deleted and a full amnesty be granted covering Louis Riel, Ambroise-Dydime Lépine*, and William Bernard O’Donoghue*, for whom the Mackenzie proposal envisaged banishment for five years. His amendment was supported by the Conservatives François-Louis-Georges Baby* and Louis-François-Roderick Masson*. In the vote only 23 Conservatives from Quebec supported it, although Mousseau had once more expected support from some of the Quebec Liberals.

On the New Brunswick schools issue Mousseau adopted virtually the same position as Masson. In 1873 he had already given vigorous support in L’Opinion publique to the cause of the New Brunswick Roman Catholics. He maintained this position, which was more nationalist than political, when John Costigan* reintroduced the question in parliament hoping to obtain an amendment to the British North America Act by which Catholics in New Brunswick would be accorded the same rights as the Catholic minority in Ontario and the Protestant minority in Quebec. This motion was rejected in the name of provincial autonomy. Once again Mousseau’s nationalist ambitions were frustrated and this led him to deplore the political dissensions paralysing the life of French Canadians as a nation. Like Masson, Chapleau, Mercier, and even Joseph-Édouard Cauchon, he began to wish that the Conservatives would unite with “the Liberals of the province, 90 per cent of whom share their Conservative principles and their national ideal.” The most natural ally, however, would probably have been the Ontario Liberals. In order to survive, Mackenzie and his followers had once more had to join forces with the supporters of Antoine-Aimé Dorion* and Luther Hamilton Holton*. Gradually, however, they lost their Reform character and progressive look, and began to display conservative tendencies. Hence they may well have been ready to repudiate their alliance with the “old Rouges” of the province of Quebec for a better matched alliance with the promoters of the party of union. This would have meant the end of the party of Sir John A. Macdonald* and Cartier, and the Conservatives of long standing could not accept such an eventuality.

While some French Canadians dreamed of an alliance, the Mackenzie government was struggling with the economic crisis which had affected the western world since the end of 1873. The Liberal party’s official policy was free trade, and it was with considerable reluctance that Mackenzie adopted certain protectionist measures. They provoked a wide-ranging debate in the house on economic policy during which, on 10 March 1876, Mousseau delivered a thoroughly documented speech, published first in La Minerve on 20 and 21 March and later as Le tarif, protection et libre échange. Mousseau advanced the tenets of Macdonald’s National Policy, which would become fashionable during the 1878 election campaign.

Having been active in the opposition, Mousseau easily won Bagot County in the general elections of 17 Sept. 1878 and his name was immediately put forward for a ministerial post in the new government. But Mousseau was not so ambitious. In a letter to Macdonald he joked about the forming of the government: “I suppose that at this moment ‘each one is showing his tricks,’ that is to say every one wants to be a minister.” He and his friends would be happy if one of the three portfolios intended for the province went to Chapleau. Mousseau was then very busy with the events following the coup d’état of the previous 2 March by which Luc Letellier de Saint-Just, lieutenant governor of Quebec, had dismissed the government of Charles-Eugène Boucher* de Boucherville. In Le 38me fauteuil Joseph Tassé* clearly explains the role Mousseau played in what the Conservatives of the day called “the downfall of M. Letellier.” Mousseau was then being pressured to act on the federal level by the Quebec Conservatives, who had been frustrated in all the measures to which they had resorted since the coup d’état: a petition to the administrator of Canada and another to the federal government, collective action and individual pressure, polemics in the papers, and so on. On 11 March 1879 he made a motion of censure in the house against Letellier, thus forcing the government to act. After a protracted, stormy debate, parliament passed Mousseau’s motion, the first in a long series of measures leading to the dismissal of the lieutenant governor of Quebec. But in the Letellier affair Mousseau was under the influence of Chapleau, then premier of Quebec. Mousseau’s political life was thereafter strongly marked and directed by the ambitions and indeed the whims of Chapleau, who was emerging as the strongest and most exacting Quebec political figure of his day.

On 8 Nov. 1880 Mousseau was summoned into the federal government as president of the Executive Council. On 20 May 1881 he became secretary of state, although he promised Sir John he would accept a position on the bench as soon as Chapleau was ready to leave the Quebec government for Ottawa, where every 19th-century politician preferred to finish his career. But at Chapleau’s suggestion Macdonald effected an exchange of posts in July 1882: Chapleau became a federal minister and Mousseau became premier of Quebec.

Because he lacked aggressiveness, the will to do battle, and the spur of strong ambitions, Mousseau was not, however, destined to play a pre-eminent political role. His appointment as a federal minister had come only with a particularly favourable combination of circumstances, and he had the reputation for not being “equal to” his portfolio and for appearing “more and more out of his depth among the other ministers.” His unfailing cheerfulness, his cordiality, his sense of humour, and his high spirits cast him rather as the ideal mediator, even scapegoat. It is understandable that politicians born to the game did not fail to take advantage of this fact. Of all the “orthodox” Conservatives, Mousseau, whose kindliness might be thought to be matched by broadmindedness, was perhaps the one most readily accepted by both factions of the party, as Chapleau claimed. He was certainly the one who would best enable Macdonald and Chapleau to govern the province of Quebec through an intermediary.

It is obvious that in this political situation the province was sacrificed to Ottawa, just as Mousseau was sacrificed to Chapleau, to the unity of the party, and to the interests of Montreal, which was gambling for its prosperity on the federal level. Returned in Jacques-Cartier, Mousseau was condemned to become a second-rate premier, especially since the province he inherited on 31 July 1882 was divided. Chapleau’s final political gesture had been the sale of the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway, the western section at a low price to the federal government and the eastern section to a syndicate formed and run by Louis-Adélard Senécal, the financial mainstay of the Quebec Conservative party. This sale had attracted criticism because it had stripped the province of its most valuable property for the benefit of Ottawa, Montreal (which would become a major terminus), and Senécal. As a result the “Castors,” a group within the Quebec Conservative party opposed to the “Senécalistes,” came into existence [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel]. Once Chapleau was in Ottawa Mousseau became the object of the Castors’ attacks and his position quickly became untenable. In the autumn of 1883 he tried to win over the Castors by negotiating the entry of John Jones Ross* and Louis-Olivier Taillon* into his government. He also secured the collaboration of a number of English-speaking Conservatives. But the Ultramontanes, followers of Trudel, refused adamantly to be reconciled with the man they called “Chapleau’s shadow.” The by-election on 16 Nov. 1883, in which François-Xavier Lemieux*, a Liberal of the Rouge school, was elected in Lévis thanks to the Castors’ support, showed the futility of Mousseau’s efforts. According to Hector-Louis Langevin*, Sir John’s lieutenant in Ottawa, Lemieux was elected “obviously out of hatred for Senécal, Mousseau, Chapleau and company.” After this defeat, union of the two factions of the Conservative party was obviously necessary but Mousseau was incapable of bringing it about, having neither the prestige nor the skill to do so. He therefore resigned in January 1884, at the request of the federal leaders, leaving the task of uniting the Conservatives and attempting the reconstruction of the provincial government to Ross, a moderate Castor.

When on 22 Jan. 1884 Mousseau became a puisne judge of the Superior Court for the district of Rimouski, he bid farewell to public life. At a low ebb, he died on 30 March 1886 in Montreal as the result of a chill. If he was only 47, when he was said to be constituted to reach 80, it was perhaps because politics had not served him as well as he had served politics.

[The career of Joseph-Alfred Mousseau cannot be studied without consulting most of the major archival collections of the political figures of his era and official publications of the federal and provincial governments. In addition to Mousseau’s writings, various newspapers and other published works provide a wealth of information and deserve mention. a.d.]

J.-A. Mousseau was the author of: Contre-poison: la Confédération c’est le salut du Bas-Canada; il faut se défier des ennemis de la Confédération (Montréal, 1867); Lecture publique . . . sur Cardinal et Duquet, victimes de 1837–38, prononcée lors du 2e anniversaire de la fondation de l’Institut canadien-français, le 16 mai 1860 (Montréal, 1860); and Le tarif, protection et libre échange; discours prononcé . . . le 10 mars 1876 (Montréal, 1876). Charles Langelier, Souvenirs politiques [de 1878 à 1896] (2v., Québec, 1909–12). Joseph Tassé, Le 38me fauteuil ou souvenirs parlementaires (Montréal, 1891). Le Canadien, 1862–86, especially 27 juin 1882; 31 mars, 1er avril 1886. Le Colonisateur (Montréal), 2 janv. 1862–27 juin 1863. Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, 1862–86, especially 1er août 1867; janvier–février 1874; 30 mai 1882. Le Journal de Québec, 1862–86, especially 31 mars, 2 avril 1886. La Minerve, 1862–86, especially janvier–février 1874; septembre 1878; 9 nov. 1880; 17, 19, 23 mai 1881; mai–juin, 26, 28, 29 juill. 1882; 31 mars–2 avril 1886. L’Opinion publique, 1870–74. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer. Canadian biog. dict., II: 290–91. CPC, 1874–84. Dominion annual register, 1886. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. P.-B. Casgrain, Étude historique: Letellier de Saint-Just et son temps (Quebéc, 1885). L.-O. David, Histoire du Canada depuis la Confédération (Montréal, 1909); Mélanges historiques et littéraires (Montréal, 1917); Souvenirs et biographies, 1870–1919 (Montréal, 1911). Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, I–IV.

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets, “MOUSSEAU, JOSEPH-ALFRED,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mousseau_joseph_alfred_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mousseau_joseph_alfred_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets |

| Title of Article: | MOUSSEAU, JOSEPH-ALFRED |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |

![L'Honorable Joseph-Alfred Mousseau [image fixe] Original title: L'Honorable Joseph-Alfred Mousseau [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.4916.jpg)