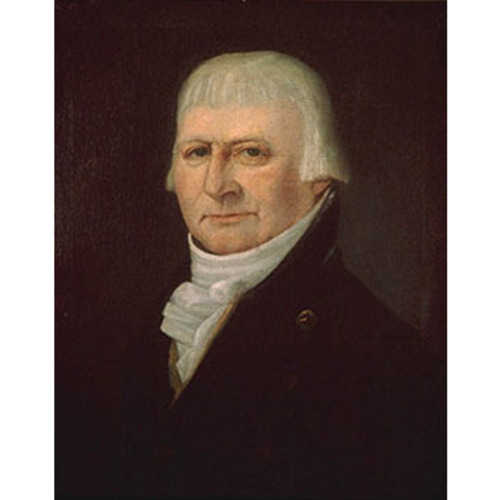

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FROBISHER, JOSEPH, fur trader and dealer in furs, politician, landowner, office holder, and militia officer; b. 15 April 1740 in Halifax, England, son of Joseph Frobisher and Rachel Hargrave; d. 12 Sept. 1810 in Montreal, Lower Canada.

Joseph Frobisher was the eldest of a family of seven. Three of the five boys, Joseph, Benjamin*, and Thomas, came to try their luck in the province of Quebec after the conquest, the first two around 1763 and their brother about six years later. They were not rich when they arrived, but they were filled with a desire to put the small capital that they did possess to profitable use. It was only by gradual steps that they became determined to dominate the fur trade in the northwest, and in fact the entire economy based on pelts [see Benjamin Frobisher].

The Frobishers’ enterprise was initially a family one, and to some degree it retained that character until 1787. The three brothers got along together and complemented one another rather well. As Benjamin had the strongest personality and a distinct talent for organization and administration, he gave up the long journeys in the west fairly early and took over the management of the company in Montreal. Joseph, who had enormous respect for his younger brother, seemed to accept this division of duties without difficulty. On 14 April 1787 he wrote to their suppliers in London: “My worthy brother, yes, I may say father died this morning after an illness of seven days only.” By contrast Thomas made his career almost entirely in the west, travelling from Grand Portage (near Grand Portage, Minn.) to the most distant trading posts. For nearly 20 years he spent only brief periods in Montreal, where on 12 Sept. 1788, having just returned from the west, he died at the age of 44. Joseph, who divided his time between Grand Portage, other posts, and Montreal, had more varied experience; yet it was limited, having been within the management of a big enterprise which had become complex and largely impersonal though it had retained certain traits of a family organization. When Benjamin died, Joseph wrote to reassure the London suppliers, “The business here and in the Upper Countries will not suffer by the unforseen accident for I can venture to say without flattery, that I am thoroughly acquainted with every branch of it.” He was, however, not unaware that he was exaggerating somewhat, since a week later he wrote to Simon McTavish that he had “never as you know taken any part in the management of the general concern of our House here.”

There is no doubt that Joseph had played an essential role in the struggles of the late 1770s and the next decade that accompanied the emergence of the North West Company [see Simon McTavish], in which the firm of Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher held an important place. He had shared his brothers’ dreams, and he had proved exceptionally effective against all competitors in the field. There had been particularly fierce rivalry with Gregory, MacLeod and Company [see John Gregory], which in 1787 still constituted a threat. As a result of all this Joseph had earned the respect of the business world. It is none the less true that questions of financing, transactions concerning the supplying of trade goods, and strategies leading to multiple partnerships with other enterprises had in part escaped his attention. For this reason Benjamin’s death was a tragic event for him.

In reality the firm of Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher was not in a sound state at that period. For ten years the company not only had been making heavy investments in the west – especially for outfitting – but had made a poor recovery from the difficult problems encountered since the end of the American revolution. Joseph pointed out in 1783, for example, that they had had to sell off at 1s. 9d. a gallon a huge stock of spirits bought for 5s. a gallon. To complicate matters, Governor Haldimand that year had secured court orders for the repayment of a debt of £14,999 in connection with the Cochrane affair [see James Dunlop]. On this matter Joseph admitted, “The public exposure of our situation soon reached our friends in England and would have put a total stop to our credit and the means of carrying on the trade to the North West (which we had established at great expence) had not friends stood forth and assured our correspondents.” The poor conditions on the international fur market had continued, so that when Benjamin died the firm of Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher was still in a critical state. In fact, the settlement of Benjamin’s estate led to a declaration of bankruptcy.

It was the old debt to the government, which had never been repaid, that lay at the heart of the company’s difficulties. Since it was no longer possible to obtain further extensions, and Joseph did not have the funds needed for full repayment, he made the government an offer to pay the debt off at the rate of 9 shillings on the pound, which was then worth 20 shillings. Thanks to the dowry that Charlotte Jobert had brought to their marriage and the support of his friends Thomas Dunn, Robert Lester, Robert Morrogh, Thomas Scott, Isaac Todd, and James McGill, who put up security for him, Joseph finally succeeded in settling this thorny question. On 22 Dec. 1787 he wrote to Dunn, “It hurts my feelings very much to find after laboring very hard for 20 years to be worse than when I began business, however there is no help for it, I am content and flatter myself that in future I will be more lucky.”

Sorely tried, humiliated, but not downhearted, Frobisher had already begun to reorganize his business. When McTavish had proposed in April 1787 that they unite their interests and suggested that he himself succeed Benjamin as administrator of the enterprise, Joseph replied, “I agree with you in opinion that throwing our interests together seems to be the most certain means of giving stability to our concern and defeating the hopes which our opponents may form from the distressing event of my poor brother’s death.” The founding of McTavish, Frobisher and Company in November 1787 entailed a reorganization of the North West Company, which made it possible for Gregory’s firm to be included as a member. In addition, the partnership with McTavish, for which Frobisher had his friends’ approval, was designed to reassure the London suppliers; the latter, added Frobisher, “will with greater confidence give us their support in a joint capacity than apart.”

The reorganization, which in theory ensured the pre-eminence of McTavish, the principal director in Montreal, and of Frobisher, the dominant figure at Grand Portage, in practice ended in reducing the influence and authority of the one who had been only a first-rate deputy. Within a few years McTavish was in firm command of the partnership, and of the NWC as a whole. Under him management became more complex and offices multiplied. Even if Frobisher still considered himself “the principal of the House,” he was now only one of a number of highly competent deputies, among them Gregory, James Hallowell Sr, William McGillivray*, and John Fraser. He complained of this to McTavish and in 1791 pointed out that his role was now limited “to outdoor business, hiring of men and public duty.” His feelings of frustration and the tensions that abounded, especially when McTavish stayed in England as he did with increasing frequency, can be readily understood. On 6 Aug. 1794 McTavish wrote to Frobisher, “Really, Sir, I am quite confounded at such inconsiderate conduct on your part. . . . I should go out in the spring and take a part in the future deliberations on the management of the business in Canada.” These calls to order did not put an end to the conflict, and in November Hallowell wrote concerning Frobisher, “I am sorry that any expression of me should seem intended to amend his feeling, we are convinced of his abilities, and have the fullest confidence in his honor, altho we have in some instances differed in opinion.”

Despite the infringements upon his status within the firm, Frobisher profited from the NWC’s successes. In the period from 1787 to 1798, the year in which he retired from the company, he succeeded in rebuilding his fortune. Not only did he occupy a place of honour in the Beaver Club of Montreal, of which he was for a long time the secretary, but he took an interest in other economic activities. In 1793, for example, he purchased a fifth of the shares in the Batiscan Iron Work Company [see John Craigie]. On 28 May 1803, with his partners in the ironworks, he bought from Alexander Ellice the seigneury of Champlain, near Trois-Rivières, which was rich in forest resources. In addition he became one of the first five shareholders in the Company of Proprietors of the Montreal Water Works, which had been set up in 1801 to supply the town and surrounding area with drinking water. He had owned riverside lots at Sorel since 1786. Like many dealers in furs Frobisher was interested in landed property on a large scale. He was less attracted by seigneurial properties than by township lands. In 1801 he sold to Edward Cartwright the islands that he owned in the St Lawrence. The following year he obtained from the government 11,500 acres in Inverness Township under the system of township leaders and associates [see James Caldwell]. Then he bought from Samuel Phillips, Jean-Baptiste Jobert, McGillivray, and Todd a fifth of Chester, Halifax, Ireland, and Inverness townships.

Frobisher was indisputably a man of substance in the society of Montreal and the province. On 30 Jan. 1779, before Anglican minister David Chabrand* Delisle, he married Charlotte Jobert, a girl of about 18 who was the daughter of the surgeon Jean-Baptiste Jobert and Charlotte Larchevêque. The latter was the daughter of a dealer in pelts and the sister-in-law of the fur trader and dealer Charles-Jean-Baptiste Chaboillez. Twelve children were born of Frobisher’s marriage, one of whom was Benjamin Joseph*. If John Fraser is to be credited, Frobisher was “a very unfortunate man in his children and connections.” He was nevertheless well placed in the merchant community and linked by marriage to influential Canadian families; he was also active in political life. He joined in the movement to obtain parliamentary institutions [see George Allsopp; William Grant (1744–1805)], and once they were in place he won election in Montreal East. However, he evidently did not attend the House of Assembly very often, since in the first four sessions he took part in only four votes. Indeed, like other fur merchants elected in 1792 – such as John Richardson*, James McGill, and George McBeath – who found it difficult to give up their businesses to take part in the assembly’s work, Frobisher refused to seek a second term in 1796. Two years before, when an association to support the British government in Lower Canada had been founded, he had signed the declaration of loyalty to the crown and had been appointed to the committee in Montreal that was responsible for recruiting other members.

An important and prestigious figure, Frobisher was the beneficiary of government patronage. He was appointed a justice of the peace in 1788 and his commission was renewed repeatedly, the last time being in 1810. He was made one of the commissioners responsible for removing the old walls surrounding Montreal in 1802. On four occasions in the period 1805–10 the government granted him commissions. In addition he helped administer a pension fund for aged voyageurs. In 1800 he held the rank of captain in the British Militia of the Town and Banlieu of Montreal, and by 1806 he had been promoted major in the 1st Militia Battalion of the town. Frobisher was also active in religious affairs. Even though he was a churchwarden of Christ Church, an Anglican congregation, he subscribed in 1792 to a fund for the construction of the Scotch Presbyterian Church (later called St Gabriel Street Church) in which the firm of McTavish, Frobisher and Company had a pew until 1805. After Christ Church burned down in 1803, Frobisher was a member of the committee for building a new one [see Jehosaphat Mountain].

During his last 20 years Frobisher had a busy social life. Around 1792 he began to put together an estate called Beaver Hall; it eventually consisted of about 40 acres outside the town, on which he had a huge secondary residence built. There, and in his house on Rue Saint-Gabriel in Montreal, he displayed hospitality on a scale that revealed both the extent and the importance of his social relationships. In 1794 he entertained Bishop Jacob Mountain* at a dinner for about 40 people, and showed him around the town and its outskirts, putting his driver and a chaise at the disposal of the bishop and his suite. Mountain appreciated this welcome and noted, “This Mr. Frobisher is an immensely rich merchant, a most worthy, honest and beneficent man. He is at the head of a house which has the first fur-trade in the country.” Towards the end of his life Frobisher was still very active socially. In January 1806, for example, he noted in his diary 16 occasions on which he dined out and 5 dinners at home at which guests were present; in February he noted only 10 dinners at home without guests.

Frobisher died in Montreal on 12 Sept. 1810. His estate was not settled finally until June 1819, three years after his wife’s death on 23 June 1816. The one sale of his personal property brought in £8,765.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 25 juin 1816; CE1-63, 30 Jan. 1779, 15 Sept. 1810. ANQ-Q, CN1-230, 15 août 1797, 2 oct. 1807, 7 juill. 1808; CN1-256, 30 July 1790; CN1-284, 11 oct. 1791; CN1-285, 24 juin, 30 août, 23 oct. 1802. PAC, MG 19, A5, 3; RG 4, B28, 115. “L’Association loyale de Montréal,” ANQ Rapport, 1948–49: 253–73. Les bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest (Masson). “Le commerce du Nord-Ouest,” PAC Rapport, 1888: 46. Docs. relating to NWC (Wallace). Jacob Mountain, “From Quebec to Niagara in 1794; diary of Bishop Jacob Mountain,” ed. A. R. Kelley, ANQ Rapport, 1959–60: 140–42. Montreal Gazette, 21 July 1808, 17 Sept. 1810. Quebec Gazette, 16 June, 3 Nov. 1785; 29 Nov. 1787; 28 Feb., 14 Aug. 1788; 19 Nov. 1789; 21 June, 20 Dec. 1792; 17 July 1794; 25 July, 12 Dec. 1799; 20 Sept. 1810; 4 July 1816; 24 Jan. 1820; index. F.-J. Audet, “Les législateurs du Bas-Canada.” F.-J. Audet et Fabre Surveyer, Les députés au premier Parl. du Bas-Canada, 205–30. Desjardins, Guide parl., 134. Massicotte, “Répertoire des engagements pour l’Ouest,” ANQ Rapport, 1943–44: 386; 1944–45: 309–401; 1946–47: 319, 324–37. “Papiers d’État,” PAC Rapport, 1890: 46–65, 209. Quebec almanac, 1800: 104; 1801: 103; 1805: 46; 1810: 58. Wallace, Macmillan dict. M. W. Campbell, NWC (1957). R. Campbell, Hist. of Scotch Presbyterian Church, 81, 95–96. Innis, Fur trade in Canada (1956). É.-Z. Massicotte, Sainte-Geneviève de Batiscan (Trois-Rivières, Qué., 1936), 78–79. G. R. Swan, “The economy and politics in Quebec, 1774–1791” (phd thesis, Univ. of Oxford, 1975), 94. W. S. Wallace, The pedlars from Quebec and other papers on the Nor’Westers (Toronto, 1954). R. H. Fleming, “McTavish, Frobisher and Company of Montreal,” CHR, 10 (1929): 136–52. Hare, “L’Assemblée législative du Bas-Canada,” RHAF, 27: 371–73. Ouellet, “Dualité économique et changement technologique,” SH, 9: 256–96. W. S. Wallace, “Northwesters’ quarrel,” Beaver, outfit 278 (December 1947): 9–11.

Cite This Article

Fernand Ouellet, “FROBISHER, JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/frobisher_joseph_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/frobisher_joseph_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Fernand Ouellet |

| Title of Article: | FROBISHER, JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |