Source: Link

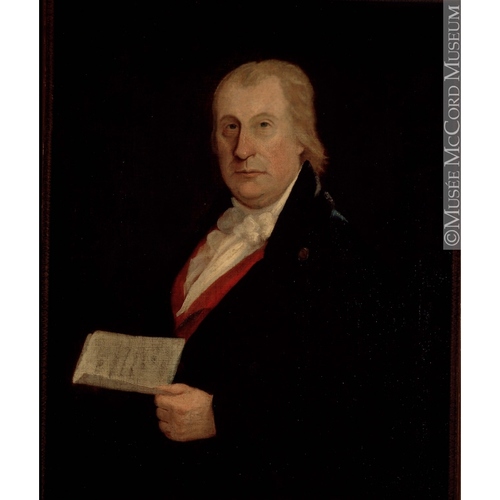

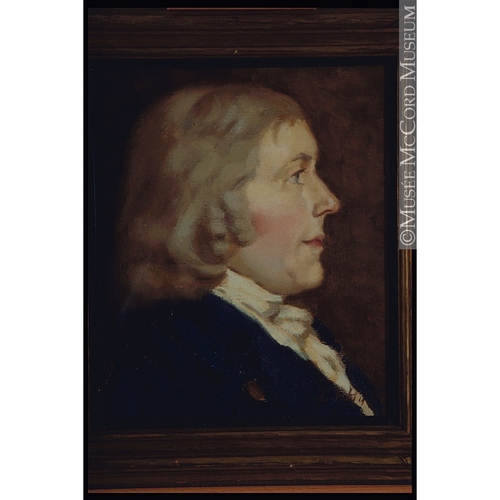

TODD, ISAAC, businessman, office holder, militia officer, and landowner; b. c. 1742 in Ireland; d. 22 May 1819 in Bath, England.

Isaac Todd had been a merchant in Ireland before he came to Canada shortly after the conquest. By February 1765 he was established in business at Montreal, and, following a disastrous fire in the city on 18 May, he submitted a claim for £150 in lost merchandise. On 23 May he received a commission as justice of the peace for the District of Montreal. He was quickly attracted to the fur trade, and his early years in it were characterized by numerous partnerships and considerable misfortune. In 1767 he posted bonds totalling nearly £1,500 as security for three traders going to various points in the interior. The following year he suffered a severe financial loss when two of his hired traders were killed by Indians. By 1769, when he invested about £900, he was in association with James McGill; that year they joined with Benjamin* and Joseph Frobisher. Along with his partners Todd again experienced a reverse when the group’s canoes were plundered by Indians at Rainy Lake (Ont.). The next year, however, the same partners succeeded in getting their canoes through to the northwest. A subsequent partnership with Richard McNeall was terminated in October 1772. That year Todd was associated with George McBeath at Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City, Mich.); they received trade goods from Thomas Walker* through Maurice-Régis Blondeau at Montreal, and in turn supplied the traders Thomas Corry and John Askin. In early 1773 Todd lost two more men killed or starved around Grand Portage (near Grand Portage, Minn.) . That spring he and McGill went together to Michilimackinac, taking with them the independent trader Peter Pond and some of his goods. By 1774 Todd was acting as the business agent at Montreal for Phyn, Ellice and Company of Schenectady, N.Y. [see Alexander Ellice].

Todd was an early leader in the political activities of British merchants in Canada. In 1765 and 1766 he was among those who petitioned Governor Murray* to reduce restrictions on the fur trade. In March 1769 he was a member of the grand jury for the District of Montreal. Considered by the British merchants as the only representative body in the colony, the grand jury was frequently used by them as a forum for criticizing the policies of the governors and recommending political, social, and economic initiatives. In 1770 Todd signed a petition in favour of an elective assembly, and in the fall of 1774 he had, in the words of Simon McTavish, “his hands full of the publick business,” having been appointed, along with McGill and others, to a committee charged both with drawing up a petition to the king and British parliament opposing the Quebec Act and with finding means to redress the merchants’ grievances. From his position on the committee, Todd was able to advise Phyn, Ellice and Company as to the best method of opposing the Quebec Revenue Act, which threatened that company’s profitable supply trade to Montreal merchants by imposing a tax on rum and spirits entering the province from the American colonies; in return Phyn, Ellice gave Todd valuable business information on the state of the fur trade from New York and on the imminent arrival at Quebec of large quantities of rum, which American traders had had shipped there by sea in order to evade the Quebec Revenue Act. Todd’s committee corresponded with similar committees in the American colonies but, when the revolution broke out in 1775, Todd remained loyal to Britain and served as a lieutenant in the British militia.

In 1775 Todd and McGill joined Blondeau and the Frobishers to send 12 canoes to Grand Portage in an association that marked the beginning of an extensive trade and presaged the formation of the North West Company. Todd and McGill formalized their association in May or June 1776 when they founded a firm called Todd and McGill; the precedence of Todd’s name probably denotes his seniority in the business. Their partnership was cemented by personal friendship. On 2 Dec. 1776 Todd was a witness at McGill’s marriage to Charlotte Trottier Desrivières, née Guillimin. The following year Todd and McGill loaded six canoes with merchandise valued at £2,700, and in 1778 Todd alone invested about £6,000. In 1779, when the NWC, a co-partnership of 16 shares, was formed by nine firms trading to Michilimackinac, Todd and McGill obtained the maximum allowable two shares. Two shares in the enterprise were held by each of two partnerships with which Todd and McGill were closely associated, Benjamin and Joseph Frobisher and McGill and Paterson, McGill’s brother John being a partner in the latter. In May 1781 Todd and McGill joined the Frobishers and McGill and Paterson in sending to Grand Portage for the northwest trade 12 canoes and 100 men with goods valued at £5,000. That year Todd and McGill became Montreal agents for the Niagara merchants Robert Hamilton and Richard Cartwright.

At the end of 1782, when the nature of the preliminary articles of peace between Britain and her rebellious American colonies became known in Montreal, the city’s fur-trade community was alarmed at the prospect of losing to the Americans the fur-trade centres of Detroit and Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.). Todd, who was in London in February 1783, was a member of a small committee promoting the interests of the Montreal merchants among government officials, and he signed memorials protesting the proposed cession of such key posts and forecasting a loss of business for the Montreal merchants if it occurred. Despite Todd’s public prognostications Todd and McGill had sufficient faith in the future of the trade on American territory to withdraw from the northwest about 1783 or 1784 and to concentrate their attention on the trade to the Mississippi and Upper Lakes regions.

Todd and McGill, although they equipped expeditions themselves, acted principally as middlemen, importing from various London firms a wide variety of trade goods. These goods arrived at Quebec and were trans-shipped to Montreal, where, they were packed for clients at Detroit, Michilimackinac, and other posts. McGill, who possessed a shrewd judgement but was temperamentally more reserved than Todd, managed affairs at Montreal and conducted most of the correspondence of the partnership. Todd, sociable and cheerful, travelled when business required it, maintaining personal contact with those upon whom depended the success of the company, or of the fur trade in general. He made return voyages to London at least four times between 1778 and 1785; in the latter year, when Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton* sent a petition from the fur traders in the pays d’en haut to the Home secretary, Lord Sydney, he referred Sydney to Todd for an account of the state of the trade.

In the period immediately following the American revolution Todd and McGill, like other companies trading to Detroit, suffered losses as a result of unstable trade conditions created by conflict between the Indians and the American army. By April 1786 the partnership was so indebted to its English suppliers, McGill informed its Detroit agent, Askin, “that Todd [who was again in London] writes me he was under the necessity of relinquishing every Scheme of business except the shipping of a few dry Goods & some Rum, being afraid to run further in debt & perhaps even meet with a refusal of further credit.” When the Detroit traders were driven that year to form a co-partnership called the Miamis Company, Todd and McGill, probably through Askin’s influence, was named its Montreal agent.

Todd remained active in Montreal’s public life. In March 1787 he was a member of the grand jury and a captain in the British militia, but his political activities, unless directly related to commerce, declined as those of McGill intensified. In the 1790s his and McGill’s principal commercial pursuits, conducted from warehouses on Rue Saint-Paul, continued to be related to the fur trade. They imported manufactured goods from Britain and tobacco and spirits from the West Indies to sell to other merchants and for their own business. In 1790 they filled 15 canoes and 10 bateaux with goods valued at £11,500. Their activities were still concentrated on the regions south of the Great Lakes. Between 1790 and 1796 they hired at least 518 engagés; of these 57 per cent agreed to go wherever they might be sent, a situation that allowed Todd, McGill and Company (as it was called by 1790) to adjust to fluctuations in an unstable field of enterprise. Of those engagés whose destination was specified in their contract 24 per cent were sent to Michilimackinac, 19 per cent to the Mississippi region, 17 per cent to Detroit, and the rest to a large number of posts. The year 1797 marked a radical departure from former practice, however; of 70 engagés known to have been hired at Montreal, only 14 per cent had no specified destination, while 73 per cent were sent to Michilimackinac.

By the 1790s Todd, McGill and Company had established a contact at St Louis (Mo.) in Auguste Chouteau, who bought their trade goods and shipped to them, via Michilimackinac, peltries gathered along the Missouri and Osage rivers. In 1794, when the Spanish government of Louisiana granted Todd’s nephew, Andrew Todd, a monopoly of the upper Mississippi trade, Todd, McGill and Company found itself in a position to monopolize the supply of the entire Mississippi valley. However, the declaration of war between Spain and Britain in October 1796, and Andrew’s death later that year, soon dashed grandiose expectations.

The concentration of the trading activities of Todd, McGill and Company on American territory was a source of apprehension to Todd, more so than it was to McGill. In May 1790 Todd, who was in London, and the London merchant John Inglis lobbied Home Secretary William Wyndham Grenville to prevent, or at least delay, the transfer to the United States of western military posts on American territory still garrisoned by British troops. The following year Todd, McGill and Company, along with McTavish, Frobisher and Company [see Simon McTavish] and Forsyth, Richardson and Company, urged Lieutenant Governor Simcoe to impress upon the British government the need to establish an independent Indian territory in the west, open to both British and American traders; in 1792 Todd lobbied for the idea in London. That April Todd, McGill and other firms complained to Simcoe of American interference with communications between Montreal and the American interior, which, if tolerated by the British government, “would be much the same as a total relinquishment of the Trade.” A pessimistic Todd wrote to Askin in August, “I have strongly recommended to the House to curtale & Lessen our connections in that Trade, for when I consider the [uncertainty] of our retaining the Posts the Warr between the Indians and Americans, and the evident fall on furrs I am convinced it is an unsafe and unprofitable business, and will continue so for two or 3 years.” In 1794 Todd and Simon McTavish submitted a memorandum to the British government stipulating the conditions that should be demanded of the Americans before the western posts could be turned over to them; of first importance was freedom of trade for the British merchants.

At the same time as Todd struggled to ensure free access for his company to the southwest trade, he sought, in case of failure, to open a door on the northwest, largely controlled since 1787 by the NWC. In 1791 John Gregory, a partner in the NWC, informed McTavish that Todd, John Richardson*, and Alexander Henry* were determined to get into the northwest trade if McGill would manage the Montreal business of a new company. McGill was not enthused by the idea of opposing the NWC, and he persuaded the others to let him negotiate entry into it with his friend Joseph Frobisher. Frobisher was soon convinced that if Todd, McGill and Forsyth, Richardson were not allowed a share in the northwest trade through the NWC, they would in combination, and with the financial support of Phyn, Ellices, and Inglis of London, constitute a ruinous opposition. On 14 Sept. 1792 Todd, McGill was accorded two shares in a new 46-share arrangement. Three years later, however, perhaps dissatisfied with proposed new conditions of partnership, Todd and McGill did not sign a revised NWC agreement. Instead they agreed with Forsyth, Richardson and two independent traders to operate for three years in the Nipigon country, but they later withdrew from the agreement under pressure from the NWC.

In the 1780s Todd and McGill had begun diversifying their activities, in part as insurance against the vagaries of the fur trade. In addition to conducting their own banking operations, in March 1792 they joined Phyn, Ellices, and Inglis and Forsyth, Richardson in signing a preliminary agreement for a bank in Lower Canada, but the project was stillborn. In 1789 they had associated with the firms of Forsyth, Richardson, Lester and Morrogh [see Robert Lester], and the merchants Thomas McCord*, George King, and Jean-Baptiste-Amable Durocher in purchasing for £3,050 the Montreal Distillery Company, of which Jacob Jordan* was formerly the principal backer in Canada. This company seems not to have yielded the expected returns; it was dissolved in 1794 and the property sold to Nicholas Montour for £1,166 that October. Todd also began to envision the supply of grain to the government as an eventual replacement for the fur trade, where all would be lost in a few years, he wrote to Askin in April 1793, “unless there is a change in the mode of Trade and expense that I scarcely think will happen.” That year Todd and William Robertson lobbied successfully in London to secure for Todd and McGill’s Upper Canadian associate Cartwright and others an exclusive sub-contract to victual the military posts on the Great Lakes. As did many other merchants, Todd and McGill moved into land speculation; through Askin in 1796 they acquired several shares in the Cuyahoga Purchase, a large tract of land along the south shore of Lake Erie. They were occasionally obliged to accept land as payment for debt. One of their largest debtors was Askin, who in 1792 owed them £20,217; he acquitted part of the sum by transferring to them land in and around Detroit. In 1798 Todd also acquired by succession all the property of his nephew, Andrew.

Todd’s growing disagreement with McGill about the future of the fur trade on American territory was probably a major contributing factor to the dissolution of his partnership with McGill by early April 1797. Five years earlier James’s brother Andrew McGill had been brought into Todd, McGill as a partner, and he had probably been groomed as Todd’s eventual successor. Todd’s ties with the trade were not immediately severed, however, since it took several years for an outfit to turn a profit or loss; in March 1798 he wrote to Askin of the capture by the French of “the richest of our Furr Ships in which we had to the Amot of £12000.” Only after August of that year did he begin to withdraw from active participation. He retired with the reputation of an authority on the trade and a father figure in the fur-trade community. In 1795 he had been admitted to the prestigious Beaver Club. The following year Simcoe wrote to one of his correspondents that the information on communications that the latter had requested was “to be gathered from Carver and Hennepin’s Voyages or rather from the conversation of such a man as Mr. Todd.” In 1804 Todd exerted his considerable influence in the fur-trade fraternity to promote the union of the NWC and the New North West Company (sometimes called the XY Company) [see Sir Alexander Mackenzie], seemingly having been, the Earl of Selkirk [Douglas] noted, “almost the only man who has maintained a constant friendly intercourse with both parties.”

From 1800 to about 1807 Todd joined with the Quebec firm of Lester and Morrogh to supply provisions to the British army in Lower Canada. He continued his activities in land speculation, alone and with McGill. In October 1801 they acquired 32,400 acres in Stanbridge Township, Lower Canada, from Hugh Finlay for £3,750. The following August Todd acquired 11,760 acres in Leeds Township through the system of township leaders and associates [see James Caldwell]. As well, by 1805, in conjunction with McGill and Askin, he had acquired other lands in and around Detroit. After the transfer of that post to the United States in 1796, the refusal of the American government to recognize all of Todd’s and McGill’s land titles, as well as the failure of the American courts to sustain their prosecutions for debt, had embittered Todd, who in 1808 declared himself to Askin “out of patience with your Rascally Country.”

Despite deteriorating health Todd led an active social life. In January 1799 Alexander Henry had written to Askin that Todd “is like myself growing old always complaining”; a year later he specified that Todd “is always complaining when his intestines are empty, but after Dinner recovers wonderfully.” The British officer George Thomas Landmann* described him about the same time as an old man who entertained “exceedingly” with numerous anecdotes of his experiences at Michilimackinac; Todd was, Landmann added, affectionately known as “By Jove,” for his favourite expression. He was sorely tried by the deaths in July 1804 of McTavish, a close friend, and of a housekeeper. “She was only 31 Years Old,” he lamented to Askin, “Lived with me near 10 Years & was Mother to a Little Girl that Calls me and truly her father.” He placed this girl in school at Quebec and established a trust fund of £1,000 for each of his housekeeper’s other two daughters. “I know of no use Money is but to do good, and to enable me to assist others,” he told Askin. “I with pleasure deprive Self of comforts I could enjoy.”

In March 1805 Todd presided at a dinner given by the Montreal merchants for local deputies in the House of Assembly. The Montreal Gazette reported the tenor of some of the sardonic toasts, including those made by Todd, denouncing a proposal in the assembly to introduce a tax on merchandise for the purpose of funding a new city jail; in February 1806, when the assembly met, those members who supported the tax had the serjeant-at-arms sent from Quebec to arrest Todd, as chairman of the dinner, and Edward Edwards of the Gazette on a charge of libel. By the time the serjeant-at-arms had arrived at Montreal, however, Todd was nowhere to be found.

Between 1806 and 1813 Todd travelled continuously – to Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada, to New York, and to England – on business and in search of relief from his numerous ailments; however, he always returned to Montreal, craving the company of old friends. A member of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, later known as St Gabriel Street Church, he was elected to its temporal committee in 1809 and later became its president. A trip to New York sparked Henry to observe in February 1810 that Todd’s society was missed at Montreal, “he being the only friend, except Mr Frobisher, who has not changed their dispositions, some from geting rich, other from having obtain’d places, &ca [which] has raised them in their own imagination above their old acquaintance.” In London the same year the ever gregarious Todd became a founder of the Canada Club, along with Alexander Mackenzie, Edward Ellice*, Simon McGillivray*, and others. By 1812, however, having survived all his friends there, he had returned to Montreal, principally to be with Henry and McGill. “Todd says he is only 68,” Henry joked to Askin in February 1811. “Todd was once much older than me but he has grown much younger at present.” On 21 Dec. 1813 Todd signed McGill’s death certificate; the demise of his friend and former partner prompted him to retire. In May 1815 he was back in England at Bath, taking mineral waters. There he undoubtedly learned of the activities of a NWC ship named in his honour, for in 1813 and 1814 the Isaac Todd had participated in a successful operation by the Royal Navy to clear the Pacific Ocean of American naval presence and to capture Fort Astoria, base of the NWC’s major competitor on the Pacific coast, John Jacob Astor. Todd seems never to have returned to Canada, and on 22 May 1819, at the reported age of 77, he died at Bath. The Montreal Herald noted that his death was “very sincerely regretted by a numerous and most respectable circle of friends and acquaintances.”

In retrospect, given the gradual American exclusion of Montreal traders from the southwest fur trade after 1800, Todd appears to have been the more prescient of the senior partners in Todd, McGill and Company regarding its main economic activity. He may already have had misgivings about leaving the northwest in 1783 or 1784, but clearly by the early 1790s he had realized that the future of the trade lay there. However, by 1792 when, under his pressure, Todd, McGill and Company did join the NWC, Joseph Frobisher and Simon McTavish had already established their preponderance in the co-partnership. Had Todd and McGill remained in the NWC from the beginning they might have proved serious rivals for the dominance of the fur trade from Montreal.

ANQ-Q, CN1-16, 27 janv., 17 févr. 1809; CN1-26, 18 déc. 1801; CN1-256, 29 May 1792; CN1-262, 2 oct. 1801. NYPL, William Edgar papers (copies at PAC). PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 74: 234–35; MG 19, A3, 24; 69; MG 30, D1, 20; RG 4, B1, 12: 4586–91; B28, 115. PRO, CO 42/5: 30–31 (copies at PAC). “The British regime in Wisconsin, 1760–1800,” ed. R. G. Thwaites, Wis., State Hist. Soc., Coll., 18 (1908): 313, 326. Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank), 4: 255. Doc. relatifs à l’hist. constitutionnelle, 1759–1791 (Shortt et Doughty; 1921), 1: 397–98, 886–87. Docs. relating to NWC (Wallace). Douglas, Lord Selkirk’s diary (White). John Askin papers (Quaife). Landmann, Adventures and recollections, 2: 172. Montreal Herald, 19 June 1819. Quebec Gazette, 1766–1806. Langelier, Liste des terrains concédés, 9. Massicotte, “Repertoire des engagements pour l’Ouest,” ANQ Rapport, 1942–43. Quebec almanac, 1788: 52. M. W. Campbell, NWC (1973). R. Campbell, Hist. of Scotch Presbyterian Church. B. M. Gough, The Royal Navy and the northwest coast of North America, 1810–1914: a study of British maritime ascendancy (Vancouver, 1971), 12–24. Innis, Fur trade in Canada (1970). L. P. Kellogg, The British regime in Wisconsin and the northwest (Madison, Wis., 1935). Lanctot, Canada and American revolution (Cameron). M. S. MacSporran, “James McGill: a critical biographical study” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, [1930]). Miquelon, “Baby family,” 182, 189. P. C. Phillips, The fur trade (2v., Norman, Okla., 1961), 2. Rich, Hist. of HBC (1960), vol. 2. Rumilly, La compagnie du Nord-Ouest. Ivanhoë Caron, “The colonization of Canada under the British dominion, 1800–1815,” Quebec, Bureau of Statistics, Statistical year-book (Quebec), 7 (1920). R. H. Fleming, “Phyn, Ellice and Company of Schenectady,” Contributions to Canadian Economics (Toronto), 4 (1932): 30–32. Charles Lart, “Fur trade returns, 1767,” CHR, 3 (1922): 351–58. E. A. Mitchell, “The North West Company agreement of 1795,” CHR, 36 (1955): 128–30. Ouellet, “Dualité économique et changement technologique,” SH, 9: 286. W. E. Stevens, “The northwest fur trade, 1763–1800,” Univ. of Ill. Studies in the Social Sciences (Urbana), 14 (1926), no.3: 167, 171, 175, 183–84.

Cite This Article

Myron Momryk, “TODD, ISAAC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/todd_isaac_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/todd_isaac_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Myron Momryk |

| Title of Article: | TODD, ISAAC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |