Source: Link

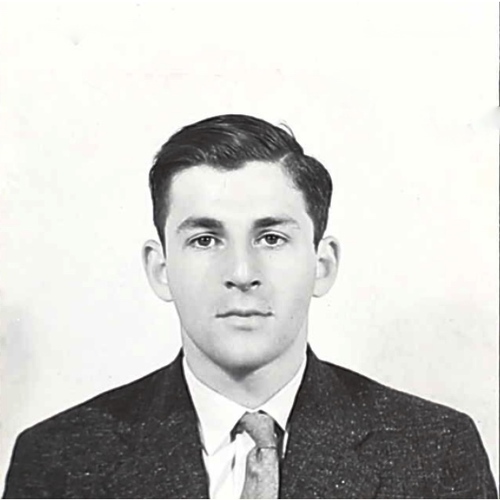

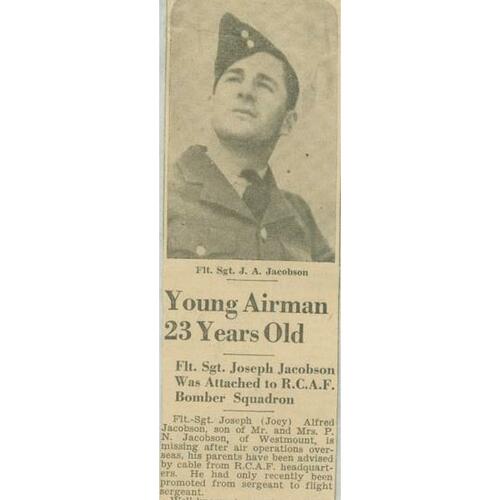

JACOBSON, JOSEPH ALFRED, letter writer, diarist, and air force officer; b. 17 Feb. 1918 in Montreal, son of Percy Nathaniel Jacobson, a businessman and playwright, and May Naomi Silver, a children’s bookstore proprietor; d. unmarried 28 Jan. 1942 near Lievelde, Netherlands.

Formative years

Joseph Alfred Jacobson, often called Joe or Joey, was raised in the prosperous anglophone enclave of Westmount, Que., where he and his family were members of the reform synagogue Temple Emanu-El. He attended Roslyn School and Westmount High School and learned to speak French. During his high school years Joe began to keep a diary, a practice that he would maintain for the rest of his life. In the fall of 1936 he entered McGill University to study commerce. A keen athlete, he played outside wing for McGill’s football team (standing five feet ten inches and weighing 160 pounds) and was its only Jewish member when it won the intercollegiate championship in November 1938. Soon afterwards, every member of the team would enlist in the armed forces. Joe graduated with a bachelor of commerce degree in May 1939. When the Second World War broke out in September, he had just started working in a factory in Preston (Cambridge), Ont., which was the main manufacturer of wooden furniture for his father Percy’s office-supply company. While there, he began considering his options with respect to military service.

Percy had high expectations for Joe. He believed that his son had what was needed to play a leading role in the national life of Canada, by which he meant the country’s business, governing, and opinion-leading circles. May and Percy were loyal to Britain and the Liberal Party of Canada. Joe seems to have shared his parents’ idealism and public-spirited values, which would be expressed in his own writings in wartime England. Yet both father and son knew that antisemitism [see Marcus Hyman*; Jacques-Édouard Plamondon*] could be a barrier to these ambitions.

Royal Canadian Air Force training

Spurred by the catastrophic events on the Western Front in the spring of 1940, Joe Jacobson left a bright, secure future in his father’s office-supply business to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force [see Sir James Howden MacBrien*]. He reported for duty at No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto on 1 July and entered No.1 Initial Training School under the newly established British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) [see William Lyon Mackenzie King]. He was selected for air observer training (involving reconnaissance, navigation, and bombing) and sent to Saskatchewan to attend No.3 Air Observer School in Regina in September. In December he went to No.2 Bombing and Gunnery School in Mossbank, where he received his air observer’s badge in January 1941 and became a non-commissioned officer with the rank of sergeant. The next month he completed his training at No.1 Air Navigation School at Rivers, Man. After a brief embarkation leave at home, Jacobson went to Halifax to await the next troop convoy leaving for Britain.

Bomber operations

Jacobson was among the first 300 Canadian air observers to arrive in Britain by 1 May 1941. Half of them would become casualties within a year. That spring, however, they constituted a significant reinforcement in the hard-fought air war against Germany. Like all BCATP graduates sent overseas at that time, Jacobson was immediately attached to the Royal Air Force (RAF) since there were no Canadian bomber squadrons in Britain.

Jacobson was posted to No.25 Operational Training Unit in Yorkshire for aircrew training on the Handley Page Hampden bomber. He was not without a sense of humour, writing in his diary on 18 July, “If there is one thing I admire about the English it is their total mastery of the art of disorganization.” On 30 July he moved on to No.106 Squadron (bomber command) in Lincolnshire. Jacobson took part in 23 sorties over enemy territory, mostly against industrial and naval targets in northwestern Germany. These operations had begun when bomber command was directed to focus its entire effort on the strategic air offensive against Germany by hitting the country’s industrial heartland. The attacks took place over the next few months, almost entirely at night, with many losses and few successes. Little known and seldom remembered, this period was the nadir of the operations of the RAF’s bomber command during the entire war. A key reason for the campaign’s ineffectiveness was the inability of aircrews to find their assigned targets. Essential radio-navigation aids were still in development, with observation limited to dead reckoning, map reading, and astronavigation, none of which could be consistently relied on when flying through Europe’s night skies. After about two months of working in these difficult conditions, Jacobson was promoted to the rank of flight sergeant, effective 1 Oct. 1941.

On the evening of 28 Jan. 1942, Jacobson and his fellow crew members were dispatched on a bombing raid against Münster, Germany. That night their Hampden bomber crashed short of the target, in a field near the village of Lievelde, Netherlands. The cause was almost certainly icing due to winter weather conditions. The entire crew of the bomber died, including Jacobson, who was only 23 years old. Three other squadron aircraft also failed to return. Jacobson was the sole Canadian in his crew. Of the 14 Canadian air observers posted to No.106 Squadron in the summer of 1941, he had been the last remaining member; most had become casualties. Jacobson was predeceased by his younger brother (who died at age 16) and survived by his parents and two sisters. His last written words, recorded in his notebook the day he died, were: “One of the first keys to happiness is an understanding of human virtues and weaknesses. Thus you rationalize away the wrongs done to you or determine to fight or counteract them – but you are not embittered or disillusioned as a result – only angry and sore which is a lot healthier. Thus the great philosopher retires until further topics pop up.”

Funeral in Netherlands

Jacobson’s aircraft was the first RAF bomber to crash near Lichtenvoorde. After discovering the wreckage the next morning, the townspeople organized a funeral for the four crew members. The ceremony, which took place at Lichtenvoorde General Cemetery on 1 February, was attended by several hundred local citizens under the watchful eyes of the occupation forces. The pastor who conducted the service declared that the four unknown men had died for a just cause. (He would later be arrested and sent to a concentration camp.) Jacobson had harboured no doubts about the justness of the cause for which he fought. He had taken his recently acquired copy of Thomas Paine’s Rights of man with him on his fatal flight.

At considerable risk, some men filmed the recovery of the crew and the funeral. The event galvanized local resistance to the occupation. Shortly thereafter, an underground network was formed to rescue downed allied airmen and return them to England. It remained active and effective until the end of the war.

Letter writer and diarist

Jacobson was one of approximately 10,000 Canadians killed while serving in the RAF’s bomber command during the Second World War. He is distinguished among them, not by his deeds but by the rich, distinctive account he left in more than 200 letters and in several diaries and notebooks. As a youth he had sporadically kept a diary, which provides insights into his mindset before the war. When he left Montreal, he and his three closest pals from McGill – Monty Berger, Gerald Smith, and Herb Ross – began a chain of correspondence. Styling themselves the “Pony Club” (an amalgam of Preston, Ont., and New York – where both Monty and Herb had gone in the fall of 1939), they continued their conversation about life, love, and duty by circulating their letters to one another in a chain. So began a vigorous discussion of the war situation in Canada and the question of enlistment. Joe’s father had also kept a diary throughout the war. After Joe left home in September 1939, he and his father began a weekly correspondence that would continue until that January night in 1942 when Joe failed to return from battle. Over that time their relationship grew, changing from that of a youth seeking and getting advice from his father to two adults confiding their hopes and fears to each other in uncertain times.

After enlisting, Joe kept a private daily diary in July 1940 and from February 1941 until he was killed in action. He also kept (contrary to regulations) an operational diary (August–December 1941) and several notebooks (October 1941 through January 1942). Believing that his views on air force operations would never pass the postal censors, he recorded them in his notebooks, which contain commentary on the problems of the bombing campaign, philosophical reflections, thoughts on politics and squadron life, notes on what he was reading, and the outline of a play about life in the air force. The week before his fatal flight, Joe had given these documents to Monty, who left them with Dan Kostoris, a friend of the Jacobson family based in Manchester, England, for safekeeping. Gerald later picked up the documents and managed to bring them into Canada without their being impounded or censored. Eighteen months after Joe’s death, he delivered them to the Jacobson family in Montreal.

Jacobson’s account is his legacy, and it constitutes a distinctive source of information about two elements of the Canadian experience of the Second World War. One is the inception and implementation of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, through which more than 130,000 men and women received instruction between 1940 and 1945. The other is the strategy, tactics, and effectiveness of the bombing campaign against Germany at its outset and nadir, and the situation of navigators and bombers in that offensive.

There is a third important aspect to Jacobson’s writing, which is the Jewish perspective on personal and communal responsibility and engagement with the war. His texts both before and during the war reveal, as few diaries or memoirs do, a young Jewish man’s evolving motivations for enlisting and persisting in the air force. On 29 May 1940 he wrote in his diary, “As a Jew I felt it is my position to accept my share of the dirty work and take the same risks as our gentile friends.” Jacobson’s writings take the reader through the last five years of his life: from his hatred of war as a boy in 1936 to his enthusiasm as a warrior for his country a week after enlisting in July 1940, and then to his reassurances to his parents of the rightness of his chosen task as he completed his operational training a year later, and, finally, to his grim determination and sense of responsibility to carry on after losing most of his fellow No.106 Squadron air observers by November 1941. Jacobson wrote in his diary (9 Nov. 1941): “One tragedy of the war – the young vigorous fellows of top notch calibre like Keswick, McIntyre, McIver, Erly, Carmichael, Dunn etc. who would be the leaders have been killed – since I am one of them my task must be twofold – first to take over their share of the responsibility – second – to try & find others to do as they would have done – that is work & struggle to give equal opportunity to as many as possible because there are more of that calibre & they must be found & given a chance.” At the end of 1942 his father observed in his diary: “Joe refused leave for the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement because he felt that it was more important to pay some of his debts to the Germans than to celebrate the sacred days. He hated the Germans on two scores. What they had done to his people. What they were trying to do to the liberty which meant more to him than his life.”

The letters and diaries written by Joe and Percy provide remarkable insights into their states of mind. There are no mysterious gaps in the record. Joe wrote letters home at least weekly, almost all of which were received and preserved. He made daily entries in his personal diary for the last year of his life. His writing illustrates his reasons for going to war: his loyalty to king and country, his abhorrence of Nazism, his enthusiasm for action, and his eagerness to test himself. Throughout the conflict, however, his motivations included his desire to affirm the honour of the Jewish people, to vindicate their place in Canada, and to rebut by demonstration the slurs, so common at that time, that Jews were unwilling to enlist and were poor fighters when they did. A week after reporting for military service in Toronto in July 1940, Joe wrote: “Whether we come out with our skins on is immaterial. The point is that we will act with courage as our predecessors are acting – we shall set an example and inspiration for our successors – a National pride and feeling shall evolve.”

The letters and diaries of Joseph Alfred Jacobson and his father, Percy, and the letters Joe received from his friends are held by the Alex Dworkin Canadian Jewish Arch. in Montreal. They are catalogued as the Percy and Joe Jacobson coll. (P0094), which includes 239 letters written by Joe, of which 139 were sent to his family, 69 to his friends (mainly the three other members of the Pony Club), and 31 to others (of which 25 were to Janine Freedman, a friend in England). There are also 31 letters from Joe’s family to him, of which 12 were from Percy and 9 from Joe’s mother, May; another 68 were sent to Joe from the other members of the Pony Club (most written by Monty Berger), and a few from other people.

The diary collection consists of Percy’s diary, 1939–45; May’s travel diaries, 1930, 1950, 1954; and six of Joe’s diaries, of which two were written during his high-school and college years (1936–39), and one during his time at No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto (July 1940). There is also a daily diary in two parts (18 Jan. 1941–27 Feb. 1942) and an operational diary (August–December 1941).

As well, the collection contains four of Joe’s notebooks along with his Royal Canadian Air Force flying log book (1940–41). Some related material, including correspondence, is in the Alex Dworkin Canadian Jewish Arch., Monty Berger coll. (P0015).

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Joseph Alfred Jacobson, 17 Feb. 1918: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 29 Nov. 2023). Commonwealth War Graves Commission, “Flight Sergeant Joseph Alfred Jacobson,”: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2648189/joseph-alfred-jacobson (consulted 9 June 2023). Library and Arch. Can., RG24, vol.27825 (Service files of the Second World War – war dead, 1939–1947), Joseph Alfred Jacobson (copy at central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=kia&id=17276&lang=eng). National Arch. (London), AIR 27/832 (No.106 Squadron: operations record book); AIR 81/11835 (Pilot Officer R V Selfe, Flight Sergeant J A Jacobson (RCAF), Sergeant D E Hodgkinson, Sergeant S H Harding: killed; Hampden AT122, 106 Squadron; aircraft shot down and crashed at Lichtenvoorde, Holland, 28 January 1942). Tom Hawthorn, “1938 McGill football champions: never to be forgotten,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 11 Nov. 2004. Henny Bennink, Bezetting en verzet [Occupation and resistance] (Aalten, Netherlands, 2005). Canadian Jewish Congress, Canadian Jews in World War II, ed. David Rome (2 pts., Montreal, 1947–48), 2 (Casualties). F. J. Hatch, The aerodrome of democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, 1939–1945 (Ottawa, 1983). Norman Hillmer et al., “British Commonwealth Air Training Plan,” in Canadian encyclopedia: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/british-commonwealth-air-training-plan (consulted 21 June 2023). Godfried Nijs, “Neegestorte Englase bommenwerper in de Besselinkschans, 28 januari 1942,” [Crashed English bomber in the Besselinkschans 28 January 1942], Lichte Voorde [Light Ford] (Lichtenvoorde, Netherlands), no.31 (May 1995), Lichtenvoorde tussen 1940 en 1950: themanummer ter gelegenheid van de herdenking van vijftig jaar bevrijding [Lichtenvoorde between 1940 and 1950: thematic issue in commemoration of 50 years of liberation]: 24–25. Thomas Paine, Rights of man: being an answer to Mr. Burke’s attack on the French Revolution (London, 1791). P. J. Usher, Joey Jacobson’s war: a Jewish Canadian airman in the Second World War (Waterloo, Ont., 2008); “Removing the stain: a Jewish volunteer’s perspective in World War Two,” Canadian Jewish Studies (Montreal), 23 (2015): 37–67.

Cite This Article

Peter J. Usher, “JACOBSON, JOSEPH ALFRED,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacobson_joseph_alfred_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacobson_joseph_alfred_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter J. Usher |

| Title of Article: | JACOBSON, JOSEPH ALFRED |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |