Source: Link

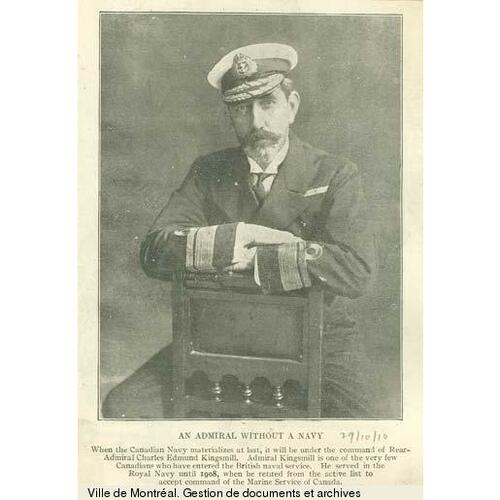

KINGSMILL, Sir CHARLES EDMUND, naval officer and administrator; b. 7 July 1855 in Guelph, Upper Canada, eldest son of John Juchereau Kingsmill and Ellen Diana Grange; m. 17 Oct. 1900 Frances Constance Beardmore (23 Nov. 1875–27 March 1956) in Toronto, and they had two sons and one daughter; d. 15 July 1935 in Portland, Ont., and was buried there in New Emmanuel Cemetery.

Charles Kingsmill was born into a family that belonged to an exceptionally close-knit social group in Upper Canada. His paternal grandfather, William Kingsmill, an Irish Anglican, was a veteran of the British army’s 66th Foot, which oversaw the incarceration of Napoleon on the island of St Helena until his death in 1821 [see Walter Henry*]. Six years later the regiment was sent to Lower Canada, and then, in 1831, to Upper Canada, where Kingsmill took advantage of a land-settlement scheme. He raised forces and commanded a militia unit during the rebellion of 1837–38 [see William Lyon Mackenzie*], was made sheriff of the Niagara District in 1840, and became postmaster general of Guelph in 1861. His first child born in the Canadas, John Juchereau, was appointed a crown attorney of Wellington County. John married Ellen Diana Grange, a daughter of county sheriff Lieutenant-Colonel George John Grange, and his sister, Helena Maria, married George’s brother Major Charles Walter Grange.

Charles was just a boy when his mother was killed in a sleighing accident in 1860. Six years later, at the age of 11, he followed in his father’s footsteps and went to Upper Canada College in Toronto, founded in 1829 by John Colborne*, William Kingsmill’s commanding officer during the Peninsular War. Had he stayed, Charles would have obtained a firm grounding for university and the professions, but in 1867 he moved on to a school in Cobourg that Dr Frederick William Barron, a former UCC headmaster, ran as a crammer for young men seeking admission to British officer-training establishments.

On 24 Sept. 1869 Kingsmill, now 14 years of age, entered the Royal Navy, in which he would have a varied and successful career. He acquired skills in seamanship that met the exacting standards of the navy in the Victorian era, was promoted midshipman on 20 Jan. 1871, and was made lieutenant on 5 Sept. 1877 while serving aboard the royal yacht Victoria and Albert. Two years later he tried to qualify as a torpedo lieutenant at the navy’s new torpedo school, Vernon (it was based on several old ships), but like so many candidates in the infancy of this branch of the service, he failed to make the grade. In 1881 he went to the East Indies station as senior lieutenant of the Arab, a new composite (wood and iron) sail-and-steam torpedo gunboat. For the next 11 years he would serve on similar ships in distant outposts of the British empire.

In 1884–85 the RN was tasked with defending Suakin, Sudan, a port of vital strategic significance in the Gulf of Aden, during the Gordon relief expedition led by Garnet Joseph Wolseley*. As part of this operation, Kingsmill supervised the disembarkation of troops at Aden and also acted as vice-consul at Zeila (Saylac) on the Somali coast. He next served aboard the six-gun screw sloop Cormorant, which was assigned to the Pacific station for four years, during which time its captain, Jasper Edmund Thomson Nicolls, died of yellow fever. Kingsmill assumed command, and his performance was praised by his superiors as well as by the ship’s company, a member of which gave him this farewell message: “On behalf of the hands you left behind … I will close hoping that you will receive yr promotion get a good ship & spend as happy a commission as we have all done in the old Cormorant.”

Kingsmill soon took the Goldfinch, a new composite screw gunboat, to the Australian station. After being promoted commander with seniority on 30 June 1891, he turned the ship over to his senior lieutenant and began a period of leave in the South Pacific, the western United States, and Canada. During his travels he met Constance Beardmore, his future wife. She came from a family of entrepreneurs: her maternal grandfather, James Miller Williams*, was arguably the first man to successfully drill for oil in North America, in Lambton County, Ont.; her paternal grandfather made his fortune from tanneries in Acton and later Bracebridge; and her father was a successful merchant. The Beardmores were well connected with professional men such as Kingsmill’s father, John, and uncle Nicol, a highly respected barrister who had a prominent role in the Toronto branch of the Navy League of Canada.

After his return to England in January 1892, Kingsmill made the transition from gunboats to cruisers. He was appointed to the armoured cruiser Immortalité in October 1893, and to the new cruiser Blenheim in May 1894. That December Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, the prime minister of Canada, died at Windsor Castle, and the Blenheim, her sides painted black for the occasion, transported his remains to Halifax. In August 1895 Kingsmill was given his first cruiser command, the Archer, which was posted to the China station. He remained with the ship for three years until he was promoted captain in December 1898. After enduring some periods on half pay and undertaking various professional courses, in September 1900 he was given command of the Mildura, a cruiser assigned to the protection of trade at the Australian station. He went first to Toronto and on 17 Oct. 1900 he married Constance, who then accompanied him to Australia.

In June 1904 Kingsmill returned to England after being selected for the war course at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich (London), and the following January he took command of the pre-Dreadnought battleship Majestic. In March 1906 he was made captain of one of the last pre-Dreadnought battleships to be built, the Dominion, which was named after the Dominion of Canada. The ship was sent on a goodwill cruise to Canada and in August went to Quebec City, where Kingsmill met Sir Wilfrid Laurier* for the first time, just as the idea of creating a national naval force, based on the fisheries protection service set up by Peter Mitchell* in 1870, was gathering momentum. The prime minister, who knew the Kingsmill family and had been alerted to Charles’s naval service by Nicol Kingsmill, took an immediate liking to Charles. Both Laurier and his minister of marine and fisheries, Louis-Philippe Brodeur*, who was impressed with Kingsmill when they met that year, quickly came to regard him as the logical choice to organize and lead a Canadian navy.

During its otherwise-successful summer cruise, the main purpose of which was to show the flag in Canadian ports, the Dominion ran aground on the shore of Quebec in the Baie des Chaleurs. The damage was slight, but both Kingsmill and his navigating officer received severe reprimands at a court martial held in March 1907. Despite the Board of Admiralty’s opinion that Kingsmill should have been dismissed from his ship, he remained in command until May, at which time he was made captain of the Repulse, a battleship in the Reserve Fleet. This demotion was no doubt related to the grounding of the Dominion, but the fact that Kingsmill received another command at all could be regarded as an expression of confidence in him, given that the Reserve Fleet was the creation of Sir John Fisher, the first sea lord of the Admiralty, who considered the fleet “the keystone of our preparedness for war.”

When Laurier and Brodeur attended the 1907 Colonial Conference in London, Kingsmill requested an interview to assure the prime minister that he was still in good standing with the RN. Laurier invited the captain and his wife to dinner. It is not known what was said between them on that occasion, but it is clear that Kingsmill, whose qualifications to develop a Canadian navy were unmatched by those of any other person with strong ties to the country, retained the prime minister’s good opinion. On 1 May 1908 Governor General Lord Grey* informed Lord Tweedmouth, the first lord of the Admiralty, that the Laurier government wanted Kingsmill to take charge of the Canadian marine service, and 11 days later Kingsmill was made a rear-admiral by the RN.

For the next two years Kingsmill ran the fisheries protection service, one of whose ships, the Canada, was used to train future naval officers. During that time he advised Brodeur and Laurier on the requirements of a navy, and along with George Joseph Louis Desbarats*, the deputy minister of marine and fisheries, he laid the groundwork for its creation. On 12 Jan. 1910 the prime minister put the issue before parliament, and on 4 May the Naval Service Act, which brought into being the Naval Service of Canada, received royal assent. The subsequent arrivals of two ships purchased from the RN (the cruiser Niobe in Halifax and the light cruiser Rainbow in Esquimalt, B.C.), along with the beginning of classes at Halifax’s Royal Naval College of Canada the following January, marked the fruition of Kingsmill’s efforts. On 29 Aug. 1911 the Naval Service of Canada was officially renamed the Royal Canadian Navy.

It was a false dawn. Laurier’s plans for an immediate expansion of the navy were halted when his Liberals were defeated in the federal election of 21 Sept. 1911 by an informal alliance of Robert Laird Borden’s Conservatives and Henri Bourassa*’s Nationalistes. An embarrassing incident on 30 July, when the Niobe ran aground off Cape Sable, N.S., had not helped the public image of the RCN, and opposition to Laurier’s naval policy proved to be a major factor in the election’s outcome. Borden, the new prime minister, sought to replace the Naval Service Act, which had authorized the construction of a small Canadian fleet, with the Naval Aid Bill, which called for a $35-million contribution to British naval shipbuilding. The bill was passed in the House of Commons but it was rejected in May 1913 by the Liberal majority in the Senate. When Kingsmill (who was made a vice-admiral on the RN’s retired list on 17 May) was asked in December to report on the state of the navy, he replied, “I have found it very difficult, if not impossible, to prepare a memorandum on the subject.” The government had no naval policy for him to comment on, and at the end of 1913 the RCN consisted of just two ships and fewer than 350 officers and men.

After World War I broke out in August 1914, Kingsmill served his country loyally and wisely. He worked in exceptionally difficult circumstances along with his chief of staff, Commander Richard Markham Tyringham Stephens*, and Desbarats, now deputy minister of marine and fisheries and of the naval service under John Douglas Hazen. Winston Churchill, the first lord of the Admiralty, advised the Borden government to devote its resources to the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and the CEF’s enormous contribution to the war effort would overshadow that of the undermanned and underfunded RCN. When hostilities began its ships were inadequately prepared for combat; Kingsmill nevertheless had to send the Rainbow to counter the German cruiser Leipzig, which briefly threatened the west coast before departing on 18 August – fortunately without having met the Rainbow – to join the squadron of Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee. On 2 September the Niobe, with the refit necessitated by her grounding in 1911 now complete, was put at the disposal of the Admiralty, but the ship was soon worn out and beyond repair, and in July 1915 she went alongside in Halifax for good. The Rainbow, which had also been placed under RN control, would continue to patrol the west coast until she was paid off in May 1917.

Kingsmill and his minuscule staff in Ottawa struggled meanwhile to provide adequate naval defences against ill-defined threats while overseeing the shipment of vital war supplies across the Atlantic (a task performed with the indispensable help of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company) and arranging the transport of Canadians who volunteered for service with the RN and the Royal Naval Air Service. The Borden government received conflicting advice from the Admiralty, which had advised the creation of torpedo-boat and submarine flotillas on the Atlantic coast in 1913, but now urged that cruisers be built. As a result, Borden was reluctant to authorize the construction of purpose-built destroyers and submarines to guard against possible German U-boat incursions in the western Atlantic and the Gulf of St Lawrence. Improvisation ruled. The minesweepers were refitted fisheries protection service ships and other civilian vessels, and yachts and tugs were regularly used to conduct patrols. In February 1917 German submarines launched unrestricted attacks on shipping in western Atlantic sea-lanes, and the RCN found itself critically short of personnel to cope with the threat. The Halifax explosion of 6 December added to the difficulties Kingsmill faced. The Germans inflicted terrible damage on fishing fleets, but the RN and the RCN, acting in concert with the United States Navy, kept shipping losses off the eastern seaboard negligible by organizing convoys that were protected by surface vessels and aircraft.

Kingsmill had a large role in coordinating these defensive operations with the Americans. In April 1918 he and the commandant of the First Naval District in Boston agreed that the USN would assume responsibility for protecting shipping as far east as Lockeport, N.S., including the outer part of the Bay of Fundy, and it consequently took over the government wharf at Shelburne, N.S., as a base of operations. Aerial patrols, proposed as early as February 1917 and rejected at that time by the Borden cabinet as too expensive, had to be conducted by the USN from Halifax and Sydney until the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service could be formed. In August 1918 Lieutenant Richard Evelyn Byrd of the USN, later to become famous for his polar explorations, arrived in Halifax to take charge of American naval air forces in Canada. At the end of November this cordial period of joint operations concluded with a farewell meeting in Halifax between Kingsmill and Byrd, who thanked his host “for the dandy time you showed us” and offered to help “should you continue your Naval Aviation as a peace time affair.” (In fact the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, created on 5 Sept. 1918 and still being organized at the war’s end, was disbanded less than a month after the armistice.)

Promoted admiral on the RN’s retired list on 3 April 1917, Kingsmill received several other marks of recognition for his wartime services. In 1916 Admiral Sir George Edwin Patey, commander-in-chief of the North America and West Indies squadron, thanked him for his “readiness to give every assistance in his power,” and the following year the Borden government drew attention to the “services given by him and his staff during the war.” This praise was brought to the notice of the Admiralty, and on 6 Feb. 1918 Kingsmill was created a kb by King George V.

In February 1919 Kingsmill, Desbarats, and Commodore Walter Hose* formed a naval committee to prepare recommendations for the future of the RCN. Under their direction the naval staff wrote 36 so-called occasional papers that were clearly influenced by the deliberations of the Imperial War Conference of 30 March 1917, during which the prime ministers of the dominions had argued that a single navy under central British authority was not practicable. In 1919 Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Jellicoe visited Canada as part of a tour of the dominions, and his subsequent report recommended a fairly modest expansion of the RCN. The cabinet put forward a reduced version of Jellicoe’s proposal in March 1920, but when the Unionist caucus rejected it, Borden decided to “carry on the Canadian Naval Service along pre-war lines.”

Charles Kingsmill submitted his resignation that month, and when it took effect on 31 December he finally left the service. In his retirement years he was devoted to his family and known for his generous hospitality. He watched from the sidelines as Hose, his successor, fought to save the RCN in the face of post-war retrenchment, and the closing of the Royal Naval College of Canada in 1922 was particularly distressing to him. Kingsmill was in every respect a creature of his age. His naval service spanned an era of enormous technological and social changes, to which he invariably adapted. During his years in the Royal Canadian Navy, unusual demands were placed on him for which his professional upbringing had not really prepared him, but he successfully handled social and political circumstances that were very different from those he had become accustomed to in the Royal Navy. Thanks to his Ontario roots and family connections, Kingsmill probably carried out his responsibilities in Canada better than any of his contemporaries in the Royal Navy could have done. After he died on 15 July 1935, his family adorned his gravesite in New Emmanuel Cemetery, near his summer home on Grindstone Island, with a remarkable headstone embellished with naval scenes and a list of family members. It is ironic and sad that the expansion of the RCN, Kingsmill’s greatest hope, did not begin until after his death, but he is rightly remembered as the father of the Canadian navy.

Sources relating to the life of Admiral Sir Charles Edmund Kingsmill are scattered, owing in part to the destruction of his private correspondence in 1939 on the recommendation of the Royal Canadian Navy’s assistant secretary, J. C. B. LeBlanc. In a memo of 7 Feb. 1939 to the chief of the naval staff, Rear-Admiral Percy Walker Nelles*, LeBlanc noted that “the correspondence would be of value to anybody who would care to undertake to write the memoirs of the late Sir Charles Kingsmill,” but concluded that the admiral “did not desire this correspondence to become a part of the official record of the Department or to be public property, otherwise he would not have removed it from his office upon his retirement” (LAC, RG24, Acc. 1992–93/169, box 116). Kingsmill’s official portrait is held at LAC, R13793-0-0.

Can., Dept. of National Defence, Directorate of Hist. and Heritage (Ottawa), Admiral Charles Edmund Kingsmill biog. file. LAC, RG24-C-1-a, vol.882, file pt.1 (Hospital ship, Prince George). NA, ADM 1/7954 (court martial proc., Charles Kingsmill, 4 March 1907); ADM 196/19/353; ADM 196/38/646. J. H. Burnham, Canadians in the imperial naval and military service abroad (Toronto, 1891). R. L. Davison, “A most fortunate court martial: the trial of Captain Charles Kingsmill, 1907,” Northern Mariner (St John’s), 19 (2009): 57–86. W. A. B. Douglas, “A bloody war and a sickly season: the remarkable career of Admiral Sir Charles Edmund Kingsmill, RN,” Northern Mariner, 24 (2014), nos.1–2: 41–63. J. G. Eayrs, In defence of Canada (5v., Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1964–83), 1. Lord Fisher [J. A. Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher], Memories and records (2v., New York, 1920), 2 (Records). G.B., Admiralty, The Navy list (London), 1869–1908. R. H. Gimblett, “Admiral Sir Charles E. Kingsmill: forgotten father,” in The admirals: Canada’s senior naval leadership in the twentieth century, ed. Michael Whitby et al. (Toronto, 2006). M. L. Hadley and Roger Sarty, Tin-pots and pirate ships: Canadian naval forces and German sea raiders, 1880–1918 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1991). William Johnston et al., The seabound coast … (Toronto, 2010). The official history of the Royal Canadian Air Force (3v., [Toronto and Ottawa], 1980–94), 1 (S. F. Wise, Canadian airmen and the First World War, 1980). “Papers relating to the empire mission, 1919–20,” in The Jellicoe papers …, ed. A. T. Patterson (2v., London, 1966–68), 2: 284–94. D. M. Schurman, Julian S. Corbett, 1854–1922: historian of British maritime policy from Drake to Jellicoe (London, 1981). G. N. Tucker, The naval service of Canada: its official history (2v., Ottawa, 1952), 1. L. P. Walsh, Under the flag and Somali coast stories (London, n.d.).

Cite This Article

W. A. B. Douglas, “KINGSMILL, Sir CHARLES EDMUND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kingsmill_charles_edmund_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kingsmill_charles_edmund_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. A. B. Douglas |

| Title of Article: | KINGSMILL, Sir CHARLES EDMUND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |