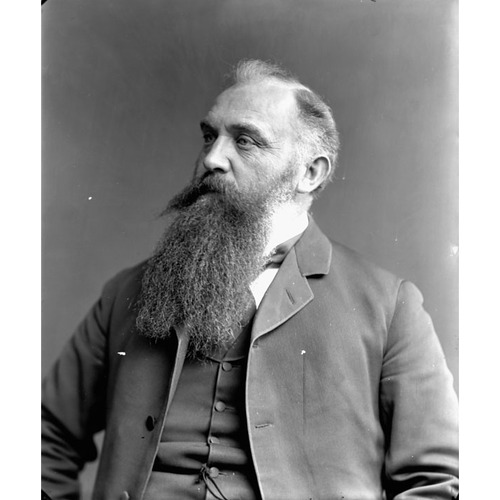

KLOTZ, OTTO JULIUS, surveyor, civil servant, astronomer, and author; b. 31 March 1852 in Preston (Cambridge), Upper Canada, son of Otto Klotz and Elise (Elizabeth) Wilhelm; m. 4 Dec. 1873 Marie C. Widenmann (Wiedeman), and they had three sons and a daughter; d. 28 Dec. 1923 in Ottawa.

Otto Klotz Sr immigrated from Kiel (Germany) to New York City in 1837 and then settled in Preston. Married in 1839 to the German-born daughter of a Wilmot Township farmer, he became a successful brewer, innkeeper, court clerk, and educationist. Otto J. Klotz attended Galt Grammar School and in 1869 entered the University of Toronto on a scholarship. Dissatisfied with its training in science, he transferred in 1870 to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he studied with astronomer James Craig Watson*. While there he met his future wife, the daughter of the German consul. After graduating as a civil engineer in 1872, he returned to Preston to practise as a surveyor. He quickly obtained his qualifications as a dominion land surveyor and, on 19 Nov. 1877, the more coveted designation of dominion topographical surveyor.

Klotz joined the federal Department of the Interior as a contract surveyor in 1879. His early work was on the prairies, although he led an expedition in 1884 to search for possible ports on Hudson Bay for a railway terminus [see Andrew Robertson Gordon*]. Beginning in 1885, he surveyed sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway belt through British Columbia. In order to tie these surveys to the prairie grid, astronomical observations for latitude and longitude were required. Since no trans-Canada telegraph line existed, he chose Seattle as his astronomical base, and, by employing western telegraphs to convey stellar readings from other points, he moved inland from Victoria to Revelstoke. In 1889 the federal government dispatched him to the Alaska panhandle to look into American infringement on reputed British territory. Klotz supported the American position on the inland boundary of the panhandle, so, when the international boundary commission was nominated in 1892, it was William Frederick King*, not Klotz, who obtained the British government’s post.

Klotz had worked with both King, the chief inspector of surveys for the interior department, and Édouard Deville, the surveyor general, during many years of western surveying. In 1890, when King became chief astronomer, he and Deville established a small observatory in Ottawa and they wanted Klotz, who still lived in Preston in the winter, on their staff. He moved to Ottawa in 1892 but continued to do fieldwork; in 1893–94, for instance, he performed surveys in the area of the Unuk River and the Bradfield Canal in the Alaska panhandle. In 1896 he formally entered the permanent civil service as a chief clerk and astronomer. He was deeply involved with King in the organization of the Dominion Observatory in the late 1890s, though they had strong differences of opinion about its site and nature. While it was being constructed, Klotz travelled to the South Pacific in 1903–4 to determine the longitudes of points along the All-Red cable line, which connected Vancouver with Australia and New Zealand. By the time of his return, the observatory was nearly ready.

During the next decade, Klotz’s work centred on geophysics, an area in which he had no training but great interest. He had already made magnetic observations during his Hudson Bay trek and had undertaken gravity measurements in Canada in 1902 and in the South Pacific. From 1907 he directed a Canada-wide magnetic survey (a field survey to measure local values of magnetic declination, dip, and strength, which were then compared to observatory standards). He was drawn particularly to the new science of seismology, where he developed the sub-field of microseisms. Following the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the American Association for the Advancement of Science formed a seismology committee, which included Klotz, who persuaded the Canadian government to join the International Seismological Association in 1907 and who would represent Canada at several international seismological conferences. Thanks to Klotz, who was made assistant chief astronomer on 1 April 1911, the Dominion Observatory became one of the most important seismological stations in the world; it issued bulletins on earthquakes and set up seismographs throughout Canada.

When King died in 1916, Klotz was his likely successor, but strong anti-German feeling in the midst of war precluded his immediate appointment. Both the observatory and the Geodetic Survey of Canada were directed by King’s former, non-scientist secretary, Wilbert Simpson, for nearly a year and a half. Internal division was rife, and morale plummeted. In the summer of 1917 the entire scientific staff signed a memorandum to interior minister William James Roche* in support of Klotz, whose appointment as chief astronomer came in September. During the interregnum, the sprawling astronomical branch, including the observatory, the Geodetic Survey, the boundary surveys, and the new Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, had broken into separate organizations. Klotz’s early administration was bedevilled by friction with Noel John Ogilvie of the Geodetic Survey and John Stanley Plaskett* of the Victoria observatory. The loss of staff under both Simpson and Klotz required some reorganization, particularly in the geophysical sections. When Canada joined the new International Geodetic and Geophysical Union and the International Astronomical Union, the national committees that were set up had Klotz as an ex officio member. At the first meetings of both organizations, in Rome in 1922, he went as one of Canada’s official representatives. During his last year in office, heart trouble curtailed his ability to work. He died in December 1923, and was survived by his wife and two sons, one of whom, Oskar*, was a renowned pathologist.

Otto Klotz appears to have been a strong personality; many liked him, others were quite repelled. He had a high opinion of himself and did not suffer fools gladly. Musical interests helped fill his spare time. His wife, Marie, caused him some concern early in the war on account of her pro-German pronouncements, but theirs seems to have been a solid relationship.

Professionally Klotz had been a lifelong organizer. He was the first president of the Association of Dominion Land Surveyors (1882–86) and was prominent in the formation of the surveyors’ associations of Manitoba and Ontario. A dls examiner in British Columbia from 1885, he served on the examining board for dominion surveyors between 1887 and his death. In addition, he was president of the Association of Mechanics’ Institutes of Ontario in 1884–85. In Ottawa, he was considered the founder of the Carnegie Library, and he served as president of both the Canadian Club and the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society. A fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Royal Astronomical Society in England, he was president of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (1908), vice-president of the American Astronomical Society (1920), and president of the Seismological Society of America (1920). He was awarded honorary llds by the University of Toronto (1904) and the University of Pittsburgh (1916) and a d.sc. by the University of Michigan (1913). Besides his official reports, which were often loaded with detailed calculations, he authored nearly 100 papers, many of a popular nature, and he was a gifted speaker on scientific matters. According to his obituary in the Ottawa Citizen, “His public lectures had a breeziness and charm that put him in instant touch with his audiences.”

Klotz headed the Dominion Observatory for too short a period to make any lasting organizational changes, but his development of geophysics – a field one might not have expected in an astronomical institution – laid the groundwork for the later eminence of the Canadian government’s geophysical research.

Papers relating to Otto Julius Klotz’s career are in LAC, MG 30, B13. The most important part of this collection is his diaries, which run unbroken from 1866 to his death. Photographs of Klotz in the LAC include PA-12295, PA-27800, PA-43037, and C-131090. His official reports as a surveyor are found in the annual reports (available in Can., Parl., Sessional papers) of the Dept. of the Interior, which also include those he wrote as chief astronomer, and in the Pubs. of the Dominion Observatory. Between 1905 and 1921 he contributed some 50 articles to the Royal Astronomical Soc. of Canada, Journal (Toronto), most of a popular nature on geophysical matters.

AO, RG 22-354, no.11510; RG 80-8-0-161, no.17966; RG 80-8-0-915, no.11278. LAC, RG 2, 4, vol.49, no.2756. Galt Reporter (Galt, Ont.), 8 July 1892. Ottawa Citizen, 29 Dec. 1923. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1898, no.16b: 20; 1914, no.25, pt.iii: 49; 1918, no.30; 1919, no.30: 182. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). J. H. Hodgson, The heavens above and the earth beneath: a history of the dominion observatories (2v., Ottawa, 1989-94), 1. R. A. Jarrell, The cold light of dawn: a history of Canadian astronomy (Toronto, 1988). J. E. Middleton and Fred Landon, The province of Ontario: a history, 1615-1927 (5v., Toronto, 1927-[28]), 3: 171-74. R. M. Stewart, “Dr Otto Klotz,” Royal Astronomical Soc. of Canada, Journal (Toronto), 18 (1924): 1-8. D. W. Thomson, Men and meridians: the history of surveying and mapping in Canada (3v., Ottawa, 1966-69), 2-3. Who’s who in Canada, 1922.

Cite This Article

Richard A. Jarrell, “KLOTZ, OTTO JULIUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/klotz_otto_julius_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/klotz_otto_julius_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Richard A. Jarrell |

| Title of Article: | KLOTZ, OTTO JULIUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 2, 2026 |