LA RUE (Larue), FRANÇOIS-ALEXANDRE-HUBERT, doctor, professor, chemist, and writer; b. 24 March 1833 at Saint-Jean, Île d’Orléans, Lower Canada, son of Nazaire Larne and Adélaïde Roy; m. 10 July 1860 Marie-Alphonsine, daughter of Judge Philippe Panet*, and they had ten children; d. 25 Sept. 1881 at Quebec City and was buried in the cemetery of his native village.

François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue received a classical education at the Petit Séminaire de Québec before he entered the Quebec School of Medicine, which gave place to the faculty of medicine of the Université Laval organized in 1853. In 1855 La Rue was the first person, and the only one that year, to receive a bachelor of medicine from the faculty. He was immediately selected by the Séminaire de Québec to go to the university at Louvain to study medical jurisprudence and chemistry. Realizing that he was wasting his time at Louvain, La Rue went to the École de Médicine in Paris, where he obtained sound scientific training. On his return in 1859 he defended the first doctoral thesis in medicine at Université Laval, and taught there, first forensic medicine and chemistry, then histology and toxicology. In 1862 he succeeded Thomas Sterry Hunt* as professor of inorganic chemistry in the faculty of arts, which in 1867 conferred an ma on him. In 1875 the federal government appointed him analytical chemist for the Quebec region under the provisions of the 1874 act to prevent the adulteration of food, drink, and drugs.

La Rue was a pioneer in several fields. His thesis on suicide is a remarkable work which interprets statistics and includes a medical and philosophical study of the moral responsibility of both rational and insane persons committing suicide. Gifted with a sharp mind and ready pen, the author frequented the bookshop of Octave Crémazie*, the meeting-place of the Quebec literary school. In 1861, with Abbé Henri-Raymond Casgrain* as moving spirit, Antoine Gérin-Lajoie, and Joseph-Charles Taché*, La Rue founded Les Soirées canadiennes, and he afterwards contributed to Le Foyer canadien. Although he had some skill as a writer, La Rue is of interest more for the number of subjects with which he was able to deal than for his literary style. His shrewd observations of material and psychological realities are well conveyed by his clear, concise, picturesque, and, when necessary, vigorous style. These qualities characterize both his didactic and his popular works, as well as his literary writings such as the “Voyage autour de l’Île d’Orléans” in Les Soirées canadiennes (1861), “Les Chansons populaires et historiques du Canada” in Le Foyer canadien (1865), Voyage sentimental sur la Rue Saint-Jean . . . (1879), and the articles, speeches, and lectures gathered in the two-volume Mélanges historiques, littéraires et d’économie politique.

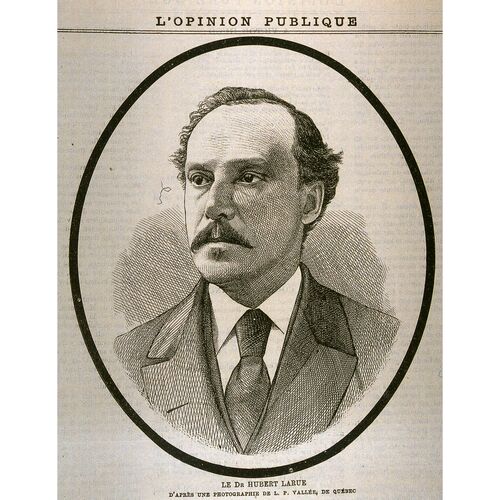

La Rue was a man of medium height, with a thick head of hair that receded with the years, making his high, broad brow more prominent. His strong jaw and piercing eyes gave him a look of severity which his moustache softened. His gait was quick and he spoke in a curt and abrupt manner. Although he demanded a high standard at examinations, his students remembered him as a professor who knew how to humanize his learning. He was a clever conversationalist and was much sought after as a lecturer; his wit made his lessons pleasant. Yet he was anxious to give guidance and stimulus to his fellow-countrymen.

A practical man, La Rue sought reforms in education and in agriculture. His article, “De l’éducation dans la province de Québec,” which appeared in the second volume of the Mélanges among other places, was an indictment of the elementary schools, which he felt were accomplishing nothing. He hoped that in the old parishes these schools would disappear and be replaced by model schools whose programmes appeared more satisfactory to him, although he was severely critical of their teaching methods and textbooks. Secondary teaching also left much to be desired, because of a lack of competent teachers and an undue emphasis on memory rather than reason. He suggested remedies and, practising what he preached, wrote textbooks for his own children on Canadian and American history, arithmetic, and grammar, which he published. He also addressed himself to adults, who spoke in a language which was deteriorating, who had ceased to read after leaving school, and who were indifferent to learning.

After his thesis was published, La Rue did not resume his scientific work, which was to be his major achievement, until 1867. From that time he was increasingly absorbed in it. He became interested in metallurgy, and also wanted to improve the prevailing old-fashioned farming customs by the use of methods based on chemistry, physics, and botany. Instead of the settlement of distant territories, he wanted to see restored the value of already depleted lands closer to home, and to set an example he worked his father’s land with his brothers. He also began to publish manuals. In 1868 he and Abbé François Pilote recommended that agricultural teaching be entrusted to specialized schools, rather than being left to normal schools as Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau advocated. In 1870 Chauveau offered the Université Laval a grant for applied science courses. La Rue had already drawn up the programme, with Abbé Thomas-Étienne Hamel, and given a course on agricultural chemistry when the university decided to refuse the grant in order to avoid any political interference. In 1873 the commissioner of agriculture and public works for the province of Quebec instructed him to draft a Petit manuel d’agriculture à l’usage des cultivateurs; by 1877 his Petit manuel d’agriculture à l’usage des écoles élémentaires, first published in 1870, was in its 13th edition.

In 1868 and 1869, about 12 years before Thomas Alva Edison patented a similar device, La Rue had obtained Canadian and American patents for a magnetic sand separator which he had invented with Quebec clockmaker Cyrille Duquet and improved with Abbé Isidore-François-Octave Audet. The invention was developed to assist William Markland Molson’s Moisie Iron Works in mining the magnetic sands on the north shore of the St Lawrence. La Rue had earlier worked in Pittsburgh, Pa, with Louis Labrèche-Viger*, the inventor of Viger’s steel, on processes for extracting iron and manufacturing steel from these ores in a single operation. As their processes differed, each had patented them in Canada and in the United States, and in 1874 La Rue had also obtained a patent for a process for concentrating pyrites to extract their magnetite. The Molson company exported iron, mostly to the United States, until it went bankrupt in 1875 [see William Molson*]. La Rue was one of those who in 1876 supported Dr Joseph-Alexandre Crevier for the post of palæontologist on the Geological Survey of Canada. But it is La Rue rather than Crevier who deserves the title of the first French Canadian scientist.

La Rue was not active in politics but, as a friend and colleague of François Langelier*, he was considered a liberal by the Ultramontanes. During the university dispute [see Ignace Bourget; Joseph Desautels], Bishop Louis-François Laflèche*, in a report to the Holy See in 1873, quoted testimony of Joseph Édouard Cauchon gratuitously accusing the Laval professors of being free-thinkers. However, when La Rue treated the sensitive subject of suicide he clearly showed his religious convictions, as he did in many other writings. He also intervened to prevent religious congregations from being subject to municipal taxes which he deemed unfair. In 1882, a year after La Rue’s death, Abbé Hamel was to take up Cauchon’s charges and to defend vigorously the reputation of his friend.

[François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue published many works in addition to his articles in Le Foyer canadien (Québec), Les Soirées canadiennes (Québec), and L’Événement (Québec). In 1859 he issued in Quebec, under the pseudonym Isidore de Méplats, Le Défricheur de langue; tragédie bouffe en trois actes et trois tableaux. His other writings were signed Hubert La Rue or F.-A.-H. La Rue, and include the following published at Quebec: Du suicide (1859); Réponse au mémoire de MM. Brousseau, frères, imprimeurs des “Soirées canadiennes” (1862); Éloge funèbre de M. l’abbé L.-J. Casault, premier recteur de l’université Laval, prononcé le 8 janvier 1863 (1863); Éléments de chimie et de physique agricoles (1868); Les corporations religieuses catholiques de Québec (1870), translated as The Catholic religious corporations of the city of Quebec (1870); Études sur les industries de Québec (1870); Mélanges historiques, littéraires et d’économie politique (2v., 1870–81); Petit manuel d’agriculture à l’usage des cultivateurs (1873); Histoire populaire du Canada, ou entretiens de Madame Genest à ses petits-enfants (1875); Les corporations religieuses catholiques de Québec et les nouvelles taxes qu’on vent leur imposer (1876), translated as The Catholic religious corporations of the city of Quebec and the proposed new taxations (1877); Petit manuel d’agriculture, d’horticulture et d’arboriculture (1878); De la manière d’élever les jeunes enfants du Canada, ou entretiens de Madame Genest à ses enfants (1879); “Éloge de l’agriculture, rapport du docteur Hubert LaRue sur le concours d’agriculture ouvert par l’Institut canadien de Québec,” Institut canadien de Québec, Annuaire (Québec), 1879: 83–101; Voyage sentimental sur la Rue Saint-Jean, départ en 1860, retour en 1880, causeries et fantaisies aux 21(1879); Petite arithmétique très élémentaire à l’usage des jeunes enfants (1880); Petite grammaire française très élémentaire à l’usage des jeunes enfants (1880); Petite histoire des États-Unis très élémentaire ou entretiens de Madame Genest à ses petits-enfants (1880). With Michel-Édouard Méthot*, he also wrote Souvenir consacré à la mémoire vénérée de M. L.-J. Casault, premier recteur de l’université Laval (1863). l.l.]

L’Opinion publique, 13 nov. 1881. C.-M. Boissonnault, Histoire de la faculté de médecine de Laval (Québec, 1953). Yolande Bonenfant, “Le docteur Hubert Larue (1833–1881),” Trois siècles de médecine québécoise (Québec, 1970), 83–97. Merrill Denison, The barley and the stream: the Molson story; a footnote to Canadian history (Toronto, 1955). Jean Du Sol [Charles Angers], Docteur Hubert LaRue et l’idée canadienne française (Québec, 1912). Jean Piquefort [A.-B. Routhier], Portraits et pastels littéraires (Québec, 1873). Léon Lortie, “Siderurgical inventions in early Canada,” Canadian Patent Reformer (Montreal), 2nd ser., 18 (1975): 65–68. Arthur Maheux, “P.-J.-O. Chauveau, promoteur des sciences,” RSC Trans., 4th ser., I (1963), sect.i: 87–103.

Cite This Article

Léon Lortie, “LA RUE (Larue), FRANÇOIS-ALEXANDRE-HUBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/la_rue_francois_alexandre_hubert_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/la_rue_francois_alexandre_hubert_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Léon Lortie |

| Title of Article: | LA RUE (Larue), FRANÇOIS-ALEXANDRE-HUBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |

![Le Dr Hubert Larue [image fixe] / L.P. Vallée Original title: Le Dr Hubert Larue [image fixe] / L.P. Vallée](/bioimages/w600.4818.jpg)