Source: Link

LESAGE, JEAN (baptized Joseph-Hertel-Jean), lawyer, politician, and businessman; b. 10 June 1912 in the parish of Saint-Enfant-Jésus, Montreal, eldest son of Xavéri Lesage, an insurance company manager, and Cécile Côté; m. 2 July 1938 Corinne Lagarde in Saint-Raymond, Que., and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 12 Dec. 1980 at Sillery (Quebec City) and was buried on the 22nd in Notre-Dame de Belmont cemetery in Sainte-Foy (Quebec City).

Background and education

The origins of the Lesage family can be traced back to the 17th century. In about 1675 Jean Lesage, his wife, Marguerite Roussel, and their son, Jean-Baptiste, journeyed from Beaumont-le-Roger, France, to New France. They settled in the seigneury of Rivière-du-Loup, near Trois-Rivières. In 1709 Jean-Baptiste married Marie-Joseph Gerlaisse in Trois-Rivières. Jean Lesage, the future premier of the province of Quebec, was born nine generations later. His maternal ancestor, Jean Côté, had married Anne Martin, a close relative of Abraham Martin*, in 1635.

Jean belonged to a family of modest means that would number eight children. At about five years of age, he entered the Jardin de l’Enfance Saint-Enfant-Jésus in Montreal, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence, an educational institution with a reputation for the quality of its five-year preparation for classical studies. In 1921 the Lesage family moved to Quebec City after Xavéri was appointed assistant manager of the Prévoyants du Canada, an insurance company. They settled in the Montcalm district, a developing area in Upper Town that was attracting white-collar workers of the francophone lower middle class. They lived in turn on Avenues Holland, Bourlamaque (De Bourlamaque), Cartier, and Brown. Jean continued his elementary education at the Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague boarding school, which was managed by the Sisters of Charity of Quebec.

In 1923 Lesage entered the Séminaire de Québec. Initially, he did better in subjects that required a good memory rather than reasoning. After some difficulty he developed a talent for mathematics, eventually being awarded, in 1930, the prize for best student in that discipline. He was not among those at the top of his class, although his marks were good and improved steadily.

During his school years Jean, a robust boy, participated in a few sports, such as tennis, hockey, and baseball, without really excelling in them. With his friends he played cards and developed a taste for cigarettes and alcohol. During this period he revealed his outstanding talents as a public speaker. His powerful voice and guttural “r’s” were exceptional and his diction impeccable. The quality of spoken language had always been a priority for his parents. He won speaking prizes at the regional and provincial level.

In 1931 Lesage obtained a bachelor’s degree with honours. He considered becoming an accountant before entering the Université Laval’s law faculty in the autumn. While a student, he sometimes went to Rue Saint-Pierre to discuss politics at the offices of his uncle Joseph-Arthur Lesage, a Liberal organizer, and Charles Gavan (Chubby)

Lesage had to earn a living. His father had lost his job during the Great Depression and his family was in financial difficulty. To this end, Jean often put his talents to good use at Liberal election meetings. His uncle Joseph-Arthur had control over the choice of young speakers, and in 1930 Jean took part in the federal campaign to support a candidate on William Lyon Mackenzie King*’s Liberal team. For this type of involvement, he earned between $5 and $10. In 1933 he enrolled in the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps and was assigned to an artillery unit. Until 1945 he devoted his evenings, weekends, and summer holidays to the Canadian Army (Reserve), which paid him a salary.

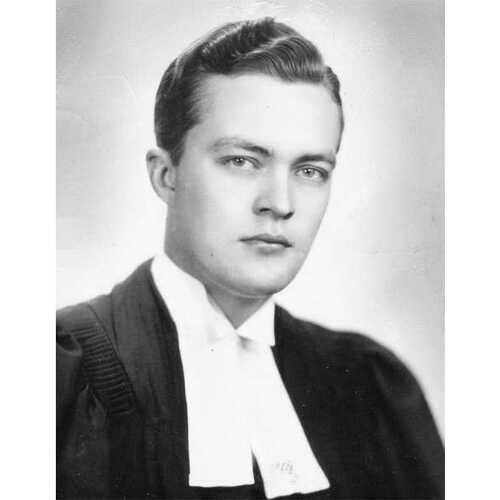

Lawyer

Lesage obtained his law degree cum laude in 1934. After passing the Quebec bar exam, he was licensed to practise law on 10 July. He had to borrow $150 from a female friend to pay his bar registration fees. As a legal adviser and subsequently lawyer for the Union des Bûcherons, founded in 1934, he defended forest workers in the mid 1930s and attempted to obtain an initial collective agreement that would improve their working conditions.

Starting in 1935, Lesage practised law with a cousin, Paul Lesage. In 1940 they joined forces with Jean’s brother Raymond. Chubby Power and Valmore Bienvenue came into the practice three years later. Power was the minister of national defence for air and associate minister of national defence in the King government, and Bienvenue was the minister of hunting and fishing in the cabinet of Quebec’s Liberal premier Adélard Godbout*. With their arrival the firm of Power, Bienvenue, Lesage et Turgeon was guaranteed access to the provincial and federal governments and solidified its reputation. Jean Turgeon, who was also a member of the group, was a school friend. Jean Bienvenue, Valmore’s son, became a partner in 1952. These developments ensured that within a few years Jean Lesage attained the status of a prominent Quebec City lawyer.

In the federal election campaign of 14 Oct. 1935, Lesage was hired by the physician Jules Desrochers, the outgoing Liberal mp for Portneuf, to give speeches on behalf of party candidate Lucien Cannon. During that time he met Desrochers’s stepdaughter Corinne Lagarde, an opera singer, whom he married in 1938. After Godbout won the provincial election of 25 Oct. 1939, Lesage, thanks to his uncle and his work as a campaign speaker, obtained the position of crown prosecutor. He was also appointed legal counsel to the Wartime Prices and Trade Board established by the King government in September. He held these posts until 1944. Leading up to the 1942 plebiscite, he campaigned against conscription.

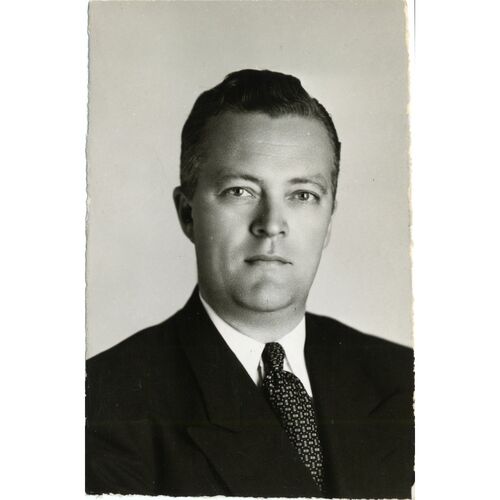

On the federal political scene, 1945–58

Election

With the agreement of his uncle and Power, Lesage ran as the federal Liberal candidate in the semi-rural riding of Montmagny-L’Islet in 1945. He knew the area well, having worked for Godbout in L’Islet during the provincial election campaigns of 1939 and 1944. On 11 June he joined the King government, winning a seat in the House of Commons with 60.67 per cent of the vote. According to the historian Conrad Black, during the 1948 provincial campaign Lesage reached a friendly agreement with Antoine Rivard*, a Union Nationale candidate, to facilitate their respective electoral victories: Rivard took the provincial riding of Montmagny, and Lesage benefited from this win in the federal election the following year. He was returned to Ottawa in 1953, 1957, and 1958. In Si l’Union nationale m’était contée …, Rivard remarked that he had an excellent relationship with Lesage: “Some of my organizers were also those [who worked for] … Jean Lesage. And I’m not telling you this to boast, but their watchword was: ‘We have two good men; we need them and we’re keeping them.’” Thus Lesage, like other federal Liberals in Quebec, formed something of a collaboration with the Unionists.

Political ideas and speeches in the House of Commons

A man of action rather than an ideologue, Lesage nevertheless believed in economic liberalism and defended individual freedoms. His political hero was Sir Wilfrid Laurier* [see Sir Wilfrid Laurier]. In his maiden speech as an mp, delivered on 24 Sept. 1945, Lesage argued the case for a “bilingual state” and Canadian unity in diversity. He also stressed the importance of a Canadian flag, citizenship, and national anthem. His favourite subjects concerned constitutional, financial, and economic issues. He advocated the repatriation of issues in areas that were still under British jurisdiction and Canada’s economic independence from the United Kingdom, and he believed that increased exports would result in full employment and economic stability. He urged free trade and state intervention that would impose rules to regulate the economy and guide Canadian production. The state, he believed, was also responsible for ensuring that every citizen had a decent standard of living.

With regard to the division of powers between Quebec City and Ottawa, on 22 May 1950 Lesage declared in the House of Commons, “I would never agree to let the federal government have a say in the whole matter of education in the province of Quebec,” as it would “involve the loss of sacred rights upon which our very survival depends.” When provincial taxation was introduced in 1954 [see Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*], Lesage came out against both decreasing federal taxation and imposing double taxation; in his opinion the claim to provincial priority in direct taxation was false. On 14 April he stated in the house: “This double taxation is exclusively due to the decision of the Quebec government which now attempts to throw the blame upon the Canadian government. This reminds me of the little boy who pulled the cat’s tail and replied to his father, who had told him to stop: ‘I am not pulling: the cat is.’” Expressing this stance in an “unfortunate speech,” as Georges-Émile Lapalme*, Quebec’s Liberal leader in 1950–58, later wrote in his Mémoires, would earn Lesage the reproach of other Liberals in his native province as well as that of the Union Nationale.

Lesage was the most methodical and hard-working member of “petit Chicago,” a group of turbulent, rather unruly francophone MPs whose feats included a vigorous opposition campaign against the adoption of the Red Ensign as the Canadian flag in 1946. The young member for Montmagny-L’Islet spoke frequently in the house, often in English, which he had learned from his mother – who in her youth had lived for several years in the United States – and during his training with the Canadian Army (Reserve). Like many other francophones he used the language of the majority to ensure that he was fully understood by unilingual members.

A variety of posts

In 1949 Lesage became vice-president of the house standing committee on banking and commerce. He was also co-chair of the joint Senate and commons committee on old age security, created on 30 March the following year. Owing to his administrative and legal knowledge and skill, he performed competently on this committee, and its work earned praise from other house members. In the autumn, Lesage joined the Canadian delegation at the fifth General Assembly of the United Nations in New York.

Lesage then moved another rung up the ladder. From 24 Jan. 1951 to 31 Dec. 1952, he was parliamentary secretary to the secretary of state for external affairs, Lester Bowles Pearson. In this capacity he was a member of numerous delegations abroad. He led the Canadian delegation during the thirteenth session of the UN Economic and Social Council, held in Geneva at the end of the summer of 1951, and the fourteenth session, held in New York beginning in May 1952. In January he had served as vice-president of the Canadian delegation during the second part of the sixth General Assembly in Paris, and in February as president-elect of the second UN conference on technical assistance, also held in Paris. These experiences in Canadian diplomacy gave him a wider perspective and would affirm for him Quebec’s presence on the international scene.

Lesage subsequently entered the Department of Finance, acting as parliamentary secretary to the minister, Douglas Charles

Minister, 1953–57

For a few months (17 September–15 December) after the 1953 election, Lesage was minister of resources and economic development in the cabinet of Louis-Stephen St-Laurent. Its youngest member at the time, he decided to give up practising law. On 16 December he took over the new Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, holding the post until 21 June 1957. In this role he was responsible for the Northwest Territories. He set up an administrative structure, established an economic-development policy, and introduced a school system for the vast territory, which had been neglected by the federal government. It was his principal achievement as a minister.

In opposition, 1957–58

The Liberal defeat in 1957 put Lesage on the opposition benches for the first time. In the election held the following year, he was one of 25 Liberal mps who rode out the Conservative storm that shook Quebec [see John George Diefenbaker]. For a while his political ambitions were checked in the federal arena; sitting in opposition was difficult. He was once more taking home the salary of an mp, and his family, who had followed him to Ottawa when he became a minister, was forced to return to Quebec City. He thought of abandoning politics to earn more money and considered returning to legal practice.

Early years on the provincial scene, 1958–60

A favourable set of circumstances

In addition to the federal Liberals’ defeat in 1958, four other major events contributed to Lesage’s rise to the premier’s office in Quebec City: Lapalme’s withdrawal from the leadership of the provincial Liberals; the natural-gas scandal, which undermined the Union Nationale; and the successive deaths of Unionist premiers Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis and Paul Sauvé*. In his book Ne bougez plus! the political scientist Gérard Bergeron* described the events as a “cascade of fortunate occurrences” for Lesage.

Since 1950 the Quebec Liberals, headed by Lapalme, had faced an apparently invincible Duplessis government. As the 1960s approached, the Liberal leader’s position was increasingly challenged. The lawyer Paul

No sooner had Lesage taken over the party than he saw “the long sought-after scandal fall fully cooked into his lap,” as Lapalme later wrote in his Mémoires: the natural-gas scandal, uncovered by Le Devoir in June 1958, which involved several Unionist ministers who were guilty of insider trading [see Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis]. Duplessis – old, ill, and shaken – nevertheless remained a formidable adversary. He did not fear Lesage, taking the view that the Liberal leader, like Lapalme, had been parachuted into Quebec City from Ottawa. Nor did he have a very high opinion of him, considering him weak in character, gauche, haughty, and pompous. A dramatic turn of events followed. On 7 Sept. 1959 Duplessis died in Schefferville; it seemed that fortune was smiling on Lesage. Yet he still had to confront Duplessis’s successor, the equally threatening Sauvé. The new premier launched a series of reforms that would make him one of the heralds of the Quiet Revolution. He quickened the pace to the point that the Liberals accused him of usurping their ideas, putting them in an extremely uncomfortable position. Sauvé was convinced that the Liberal leader would lose the struggle. On the morning of 2 Jan. 1960, Quebec was in shock: Sauvé was dead. In his Mémoires, Lapalme would write, “In politics, I had always had to blast my way through to the way ahead: for Jean Lesage, obstacles disappeared by themselves.” The future now looked promising for the Liberals. Sauvé’s replacement, Antonio Barrette*, called an election for 22 June.

Building his team and the Liberal platform, 1960

Even with a new leader, the Liberal Party did not constitute a credible force in 1958; it had ideas but as yet no platform. In forming his team, Lesage could count on a number of people: ex-colleagues from Ottawa, such as Bona

The Liberal platform of 1960 was the work of Lapalme, who had developed it during his years in opposition. Written the previous summer, it first materialized in a voluminous manuscript (published in 1988 in Montreal as Pour une politique: le programme de la Révolution tranquille), to which was added a rather motley collection of party resolutions passed at regional and provincial conferences between 1950 and 1959, along with proposals from Université Laval expert advisers such as Maurice

The 1960 election

The Liberals immediately began campaigning with a leader, its équipe du tonnerre (dream team), and a platform. They fought against a divided Unionist party, which had no real vision and, despite initiatives that seemed like a kind of political marketing, they continued to use its old electoral tactics [see Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis]. Taking the opposite tack, Liberal organizers found ways to employ political advertising that reached a new level. They took their cues from the approach of American presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight David Eisenhower, who had recourse to marketing studies, slogans, and television. They used opinion polls to orient their advertising strategy and television to highlight their candidates. The 1960 election campaign became one of the most widely covered by the media in the province’s history, and Lesage’s performance was superb. His presence, eloquence, and powerful voice were admirably suited to well-chosen slogans such as C’est l’temps qu’ça change! (It’s time for change!). In Souvenirs et confidences, Arsenault would write that Lesage was “one of the greatest crowd-pleasers of his generation.” Victory, however, was not a sure thing.

The level of participation in the June 22nd election was 81.66 per cent – at the time the highest in Quebec’s history. The result was close: the Liberals drew 51.4 per cent of the vote; a difference of almost 100,000 votes separated the two parties. In many ridings the Liberal candidates won by narrow margins; a shift of a few hundred votes would have ensured the return of the Unionists to power. Lesage took the riding of Québec-Ouest. The Liberals nevertheless appeared strong: the party elected 51 mlas and the Union Nationale 43. The former were backed by voters in Montreal and Quebec City, whereas the Unionists remained strong in the regions. On election night at the Quebec Coliseum, Lesage declared on Radio-Canada: “It is a victory for the entire population.… I am very confident … that we can give our province an honest government, with a sound administration and assured progress.” He ended by stating that fear had “changed sides.”

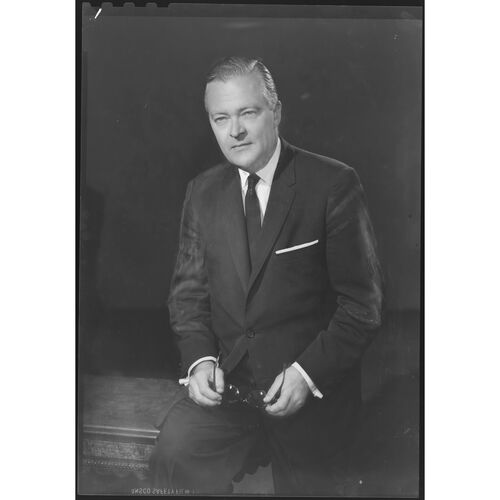

Premier, 1960–66

Origins of the Quiet Revolution

The 1960 election marked the beginning of an important period in Quebec’s history: the Quiet Revolution. The expression apparently originated during an exchange between Lesage and Brian Felix Upton of the Montreal Star. During a press conference early in 1961, Upton is said to have asked, in English, “This is a revolution, Mister Premier…?” Lesage apparently replied, in English, “If it is a revolution, it is a quiet revolution.” The term would describe the years between 1960 and 1970, when Quebec was to experience an unprecedented wave of reforms. Taking over the role of the clergy in many spheres, the state used its leverage to modernize education, health care, social services, culture, the status of women, economic development, and international relations. Lesage, who had apparently been the first to use the expression, was also the man largely responsible for such tremendous progress.

Team

Lesage’s initial task was to form his cabinet. During his two mandates (1960–62 and 1962–66), the premier knew how to surround himself with the right people: he was not afraid of strong personalities, whether they were ministers or advisers. The dream team included, among others, Lapalme, Marler, Gérin-Lajoie, Lévesque, Hamel, Saint-Pierre, Pinard, Lafrance, Arsenault, and Bertrand. They were joined in 1961 by journalist Pierre

An equally exceptional team of deputy ministers and advisers supported the cabinet. Among them were Claude Morin in federal–provincial affairs, Claude Castonguay* in social welfare and health, Guy Frégault in culture, Arthur Tremblay in education, Roch Bolduc in public administration, Jean Deschamps in industry and commerce, Louis-Philippe Pigeon in legislation, Michel

First mandate, 1960–62

Ironically, in making his program a reality, Lesage initially benefited from the provincial tax he had condemned Duplessis for introducing in 1954. He also made the most of the healthy state of public finances, a legacy of the economic conservatism of previous governments. Taking inspiration from federal practices, he instituted the monitoring of public spending and increased government revenues to pay for necessary, but costly, reforms. He was not afraid to borrow on foreign markets or impose higher income and other taxes. A greater contribution from the federal government was helpful. Expenses rose, however, in keeping with the tremendous needs associated with both an increasing population and the former Unionist government’s inertia in several spheres. Between 1960 and 1966 expenditures would quadruple, and the gross domestic product increased by half; public investment favouring economic growth resulted in the rise of personal income per capita by 38 per cent.

The purpose of huge government investment in economic development was to give the province’s francophones control over their economy. To promote the exploitation of natural resources for Quebec’s benefit, in 1961 the Lesage government created the ministry of natural resources, for which Lévesque took responsibility. Drawing inspiration from the Economic Advisory Council, which was established in 1943 by Godbout but moved to the back burner the following year by Duplessis, the government created, also in 1961, the new Quebec Economic Advisory Council. A year later the General Investment Corporation of Quebec was set up to support the foundation and development of industrial and commercial companies with the aid of public and private funding. As reported in La Presse (15 Sept. 1962), the historian Lionel Groulx* approved of Lesage’s actions: “I cannot help but admire the courage of Mr. Lesage when he says: ‘The age of economic colonialism is over in Quebec.’ It is the first time a premier [has] used such language in Quebec.”

Drawing on his talents as a lawyer, Lesage reviewed draft legislation. As finance minister he oversaw expenses with his right-hand man, André-J. Dolbec, controller of the treasury office, which Lesage reorganized; in 1961 the treasury office became the treasury council. Lesage was president of this body, which was charged with improving the management of revenue and expenses and taking responsibility for every aspect of the civil service. Making good use of his experience in Ottawa, he set up a non-partisan administration that recruited through competitions, created new job descriptions, and improved working conditions and salaries. Recruitment was from the private sector, universities, and the federal civil service. Between 1960 and 1965 the number of civil servants rose from 36,766 to 56,258. This first generation of civil servants, who were vital to the Quiet Revolution, were deeply influenced by Lesage’s reforms.

In health care Quebec became a welfare state. A government system of hospital insurance was established in 1961 [see Alphonse Couturier*], which allowed free access to hospital care for everyone.

Also created that year was the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, which represented, as Lesage stated in the Legislative Assembly on 2 March, “the soul of our people.” His aim was to ensure that arts and literature would flourish and expand both within and outside the province. Under his jurisdiction were the French Language Bureau, the Extra-territorial French Canada Branch, the Provincial Arts Council, and the Historic Monuments Commission. The tenacity of ministers Lapalme and Laporte as well as Deputy Minister Frégault ensured that the promotion of culture has remained – sometimes in spite of the premier and some of his other ministers – a great achievement of the Lesage government.

Concerning education, in the spring of 1961 the government passed a set of 12 laws, known as the Grande Charte de l’Éducation (Magna Carta of Education), guaranteeing every child the right to education. The measures concerned, among other things, free education, compulsory school attendance until the age of 15, scholarships, professional development for teachers, and the establishment of the royal commission of inquiry on education, also known as the Parent commission [see Alphonse-Marie

The team also dealt with Quebec’s role on the international stage. Encouraged by Lapalme and by the president of France, Charles de Gaulle, and its minister of cultural affairs, André Malraux, the province formed a special relationship with France and other French-speaking countries. On 5 Oct. 1961, during a visit to France, where he was received with the honours accorded a head of state, Lesage opened, in Paris, the Maison du Québec (three years later it became the Délégation Générale du Québec). The following day Le Devoir reported: “Mr. Lesage declared that the people of French Canada are aware of its possibilities and its place in the world. It is to fill that place … that Quebec is establishing a legation in Paris.” Its mission was to develop relations and exchanges in the areas of the economy, culture, tourism, immigration, and the francophonie. France officially recognized the Délégation Générale du Québec in 1965 and granted it the privileges of an embassy. In 1961 the government had replaced Quebec’s New York commercial agency with a general delegation. A delegation was opened in London in 1962 and an economic office in Milan, Italy, three years later. In international relations, Lesage acted like a veritable head of state.

1962 election and the nationalization of electricity

Such a pace of change could not, however, please everyone. Maurice Lamontagne, the Québec-Est Liberal candidate who was defeated by the Social Credit representative Jean-Robert Beaulé in the June federal election, gave his analysis of the situation in September in “Plaidoyer en faveur d’une politique humaine” (of which Le Devoir published a few excerpts on 18 Dec. 2003). In his opinion, what people particularly remembered of the 1960 Liberal platform were the slow-to-materialize promises concerning the unemployed, farmers, and social security. “The politics of grandeur,” he stated, “has tried to reach its goals too soon and left the people behind.” On the eve of the election not everyone agreed with the Liberals’ broad policies, especially those in regions with high unemployment, and neither did farmers or low-paid workers. The policies were outside their concerns and caused misunderstanding. The major move to secularize hospitals, which could offend Roman Catholics, drew criticism: it was said, for example, that hospital insurance would benefit only hospitals and doctors. The fiscal burden was also a source of dissatisfaction. The Lesage government had promised to introduce reforms while not increasing income and other taxes; however, the opposite occurred, especially with the extension of the sales tax province-wide for school purposes.

Liberal Party members had their own grievances. Several militants could not understand why they were shown no favouritism and why Unionist civil servants had kept their jobs. But in accordance with its program, the government had taken steps to abolish favouritism; these included the awarding of contracts based on public tenders and the establishment of a non-partisan civil service. Some Liberals, waiting in vain for their turn to reap the profits of patronage, believed that their party had forgotten them. Divisions were also felt in the cabinet. Maintaining cohesion among extremely talented, very strong-minded people proved difficult. Some believed that Lévesque lacked discipline: he arrived late for sessions and showed no respect for ministerial solidarity.

Party unity was rebuilt during a meeting at Lac à l’Épaule on 4 and 5 Sept. 1962. After a lengthy discussion, followed by explanations from Lévesque about the reasons for and ways of nationalizing electricity, Lesage, seeing that his team had reached a consensus, proposed that they go to the people. The 1962 election campaign was similar to a referendum campaign: Lesage asked voters to validate the nationalization of electricity, and Lévesque tried to convince them of his plan’s merits. Brilliantly led by the two men and bolstered with the powerful slogan Maîtres chez nous (Masters in our own house), the campaign led to the first televised leaders’ debate: Lesage and Daniel

In 1964, the sociologist Maurice Pinard and the Social Research Group demonstrated that Lesage had played a crucial role in the 1962 campaign and confirmed that the majority of Quebecers were satisfied with the Liberals’ achievements during the two preceding years.

Second mandate, 1962–66

As had been the case during Lesage’s first mandate, the first two years of the government’s second term were especially intense. In collaboration with his team, the premier completed initiatives and proposed new ones.

The government followed up on the first volume of the Parent commission’s report by establishing the education department in 1963. Lesage threw his weight behind the report despite his past declarations, including that of 15 Nov. 1960 in the Legislative Assembly, that “there is no question and there will never be a question under my administration of creating a ministry of public education.” Establishing the Family Superior Council and recognizing the legal status of married women were added to the important achievements made the following year.

To strengthen citizens’ control over the province’s development, other large state-owned businesses were founded. The purpose of Sidbec, established in 1964, was to create an integrated steel industry that would promote the organization of heavy industry. In 1965 the Quebec Mining Exploration Company was set up to encourage exploration and extraction of underground mineral deposits. Also that year, the Quebec Deposit and Investment Fund was launched to manage the funds of pension and insurance plans, including, first and foremost, the Quebec Pension Plan, and invest them in public or private companies. The creation of Quebec Deposit and Investment Fund was an autonomist initiative as important as the provincial tax since it helped to increase the province’s financial independence.

When the Quebec Pension Plan was introduced in 1965, it became compulsory for every worker aged 18 and over to contribute – through salary deductions and an amount collected from employers – to a public-pension fund to which employees had access upon retirement. While negotiating the system’s setup, Lesage found money by forcing the Pearson government to agree that Quebec would opt out of participating in 29 joint programs in exchange for fiscal compensation that would be used to administer the Quebec Pension Plan as well as, for example, student loans, hospital insurance, agricultural development, and rural planning. To fight off attempts at federal intrusion and defend Quebec’s constitutional rights, Lesage relied on his talents, his impressive record, and the know-how of his immediate entourage, especially that of his expert adviser Morin. The first pension plan cheques would be paid on 30 Jan. 1967.

In the middle of its second term, the Lesage government ran out of steam. The great solidarity of 1962 crumbled. Lévesque, as undisciplined as ever, eclipsed others with his popularity. Cabinet dissent arose during discussions about the allocation of money. Embittered by the underfunding of culture, Lapalme finally resigned in 1964. Gérin-Lajoie, who always wanted more, usually succeeded in getting what he needed, which exasperated his colleagues. Challenges to the leader were brewing. According to Gérard Brady, one of Lapalme’s most loyal staff members, the Liberal Party split into two clans: the Quebec City clan, which focused on the chief, and the Montreal clan, which emphasized the team. Cabinet ministers did not work together harmoniously; they dealt individually with their files, found little reason to respect party discipline, and did not hesitate to leak information to the media to force the premier’s hand or the compliance of their colleagues. The dream team was beginning to fall apart. The media spoke of the slowness in implementing reforms, and Lesage was accused of holding back his more progressive ministers.

Quebec’s social climate was also deteriorating. On the trade-union front, for example, hospital employees, who had had government support since the introduction of hospital insurance in 1961, became aware of the deficiencies of their working conditions compared with those in other provinces. Workers went out on illegal strikes. The situation was tense.

Lesage aggravated matters with his ill-judged comments. Quoted out of context and blown out of proportion, they showed his arrogance and contempt and undermined his credibility. For example, on 16 March 1965 (as reported in Le Devoir the following day), Lesage presented to Legislative Assembly press members the white paper that had been tabled in the commons on the Fulton–Favreau formula (a federal bill to change the British North America Act and repatriate the Canadian constitution) and then justified his refusal to submit it to a referendum by asking, “How do you expect me to explain this to uneducated [citizens]?” In the assembly, Unionists such as Johnson and Maurice Bellemare quoted those words at every opportunity. During the 1 April session, Lesage explained that he had meant “uneducated about the constitution.” In the assembly he was increasingly insufferable, appearing haughty and ill at ease. The Union Nationale members, including Bellemare, took advantage of his fits of anger. His Friday temper tantrums were notorious, and Johnson often found ways to prompt the premier to fly into a rage, which made headlines in the Saturday media and contributed to his poor image.

Furthermore, the nationalist question was causing headaches. In 1963 the Front de Libération du Québec, which wanted to achieve independence by turning to political violence, set off bombs for the first time. That year the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale, which advocated independence, was established as a political party, and the Ralliement National followed in 1966. The province’s political status was much debated in the Liberal Party, which had no definite stand on this fundamental question. The result was that, stuck with the Fulton–Favreau formula (to which he had agreed in 1964 and would reject in 1966), Lesage had no control over constitutional arguments, either against the supporters of independence or within his own ranks.

At a meeting with members of the Sainte-Foy Chamber of Commerce, Lesage explained his position, using the opportunity to reply to his Ontario counterpart, Conservative John Parmenter Robarts*, who maintained that the Canadian constitution must not be altered to meet the short-term demands of a minority. Le Soleil (15 Dec. 1965) reported Lesage’s answer: “It is futile to think that [it is possible to] succeed in containing modern-day Quebec within an administrative, political, or constitutional framework in which it would feel hampered in its efforts [to achieve] self-affirmation and fulfilment…. The advent of a special status, if such were the case,… would have to occur without a regrettable imbalance. I would go even further: it could be thanks to Quebec’s obtaining a special status that Canada will truly survive.” Under the special status that he hoped for, Quebec would administer all its social security programs; develop its resources; acquire broader powers in numerous fields, including international relations; initiate changes in some federal institutions, such as the Supreme Court of Canada; and guarantee bilingualism in the federal administration and government. In addition, it would appoint its lieutenant governor, choose its senators, and establish a constitutional court.

In 1962 rumours had begun to circulate in the francophone and anglophone media that Lesage would return to Ottawa to replace Pearson as the head of the federal Liberal Party. Pearson would later recount in his memoirs that, at a meeting in Florida in January 1965, he suggested Lesage join him in Ottawa, initially to become a minister and then to succeed him. In his opinion, Lesage “seemed very surprised, but pleased.” Lesage replied that he could not leave Quebec before the next provincial election, but he did not reject the idea. A tour of the Canadian west, from the end of September to the beginning of October, could have provided him with an excellent springboard. His speeches, however, which were ill-suited to their audiences, were received coldly by the public. Lesage returned home with the impression that the rest of Canada was not ready to accept his province as it was. Neither did the arrival in Ottawa that year of Liberal mps Trudeau, Pelletier, and Marchand make his life any easier. Trudeau believed that the premier’s successes at federal–provincial conferences had undermined federal authority, and he had harsh things to say about a special status. According to his account in Jean Lesage et l’éveil d’une nation, André Patry, then a technical adviser for the Commission Interministérielle des Relations Extérieures du Québec, knew that his friend Lesage “would do his utmost to … keep [Trudeau] out of the Liberal leadership race.” In the end, Lesage did not seriously reconsider the idea of returning to the federal scene.

1966 election

A pre-election poll for the 1966 provincial contest looked very favourable for the Liberals: 63 per cent of the population intended to vote for them. Yet public opinion was increasingly negative. Some of the reasons for discontent voiced in 1962 remained: too heavy a tax burden and the party’s struggle against favouritism. Liberal representatives of rural ridings were still very angry.

Other grounds for criticism arose as school reforms went ahead. The government was reproached for removing religion from schools. The premier received letters, some from members of the clergy, condemning what were perceived as attacks on religion. On the eve of the election, Le Devoir (4 June) reported his affirmation of his religious beliefs: “I, Jean Lesage, a close friend of His Eminence, who sends my children to a denominational school, am accused of wanting to remove the crucifix from schools. It’s a fantasy!”

The centralization of elementary schools and the regionalization of secondary schools also gave rise to objections that such measures would dehumanize education. For Johnson, the development of school busing, which obliged students to bring their lunch with them, was a curse. In his interview for “Mémoires de députés,” Gérin-Lajoie recalled that childless people of independent means, especially in rural areas, were opposed to school taxes, another subject of repeated complaints.

During the campaign, Lesage wanted to assert his status as the star of the party and thereby bolster his leadership. He was sometimes rather jealous of his colleagues’ success with crowds, including Lévesque’s. The campaign, centred as it was on the premier, was intended to project an image of strength. For the Unionists, however, it was precisely the leader who was the weak link in the Liberal team. Lesage spared no effort: accompanied by his wife, he toured extensively while his ministers remained on the sidelines. Compared with his work on previous campaigns, his performance was very poor. For example, on 26 May Montréal-Matin published an article about an altercation that had taken place opposite the legislative building the previous day. Lesage was walking by a group of picketing public service professionals who had been on strike for some weeks. One of them was holding a sign that read “He who educates himself impoverishes himself.” Lesage shouted, “What is that supposed to mean?” He furiously wrenched the sign from the picketer’s hands and destroyed it. “What you are doing is shameful!… It is not professional.… I’m not proud of ‘my’ professionals,” blurted the premier. The picketers responded, “[We] are not proud of you.” Lesage “turned on his heel” and stormed off. Montréal-Matin concluded that Lesage, “now in a constant state of stress,” had “yesterday … lost his self-control.” This incident, which was picked up by major newspapers, and other similar events damaged his and his party’s campaign.

On 5 June – election night – the Liberal Party won the majority of votes but was relegated to the opposition benches. The Union Nationale garnered 40.8 per cent of the vote and 56 seats, whereas the Liberal Party received the support of 47.3 per cent of the electorate and took 50 seats. The Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale and the Ralliement National obtained 5.6 per cent and 3.2 per cent respectively, with none of their candidates being elected. Clearly, some who had cast their ballots for the Liberals in 1960 and 1962 had gone over to the Rassemblement. In several ridings the Union Nationale took advantage of the divide and slipped in between the third parties and the Liberals. Lesage, elected in the new riding of Louis-Hébert, did not agree with the analysis. In a 1980 interview with Jean Larin, a journalist at Radio-Canada, he would claim that his defeat had had nothing to do with the arrival of the separatists. In his opinion, there were two reasons for his rejection in rural areas: the earliest contributions to the Quebec Pension Plan having come into effect (regarded as taxes, they appeared on pay statements in January 1966) and the amalgamation of schools, which was most evident in the need to bus pupils. Paul-Marie Lapointe, editor-in-chief of Magazine Maclean, wrote in July 1966: “Farmers, workers, and young people have been the main victims of the decay of the Quiet Revolution. It is they who brought the government down.”

Lesage hesitated before accepting the democratic outcome. Morin recorded that the day after the election, when Lesage returned to his office, he told his colleagues: “I have not been defeated.… You don’t leave when the people want you to stay. Johnson has even fewer votes than [he did] in 1962 and I have six more percentage points than he does.” He had a few options: refuse to resign and wait for a defeat in the assembly; request judicial recounts (there were rumours of electoral fraud); suggest to his friend Lieutenant Governor Hugues

Leader of the opposition, 1966–70

A democrat, Lesage took on the role of opposition leader and mla. He made a major shift by breaking with his party’s most autonomist wing, as evident in his attitude following the sensational visit of President de Gaulle in 1967. After a lengthy Liberal meeting Lesage held the Johnson government responsible for the French president’s famous declaration, “Vive le Québec libre!” On 29 July L’Action quoted his reaction: “What should have been an important step forward for Quebec ended in great discontent for the majority of citizens, a growing anxiety among those who should normally be investing in Quebec’s future, and the surfacing of regrettable anti-Québécois sentiment in the rest of Canada.” This attitude cost the Liberals one of their most brilliant mlas, François Aquin, who subsequently sat as an independent. Lesage drew a great deal of criticism. The mail he received on that occasion, although it contained a few letters of support (often from anglophones), was harsh: people accused him of narrow-mindedness, hypocrisy, lies, and opportunism, and claimed that he had betrayed his watchword, “Masters in our own house.”

The Liberal Party, once transformational, an advocate and achiever of bold reforms, was unable to redefine the province’s status within the Canadian confederation. In particular it alienated a large part of Quebec’s vital forces, especially the young. This failure did not occur, however, for want of effort. In his interview with Larin, Lesage explained dispassionately that in the autumn of 1966 he and Lévesque had discussed their respective positions on the status of the province in an attempt to convince each other. According to Lesage, they calmly agreed that their viewpoints were irreconcilable and they would submit them to a Liberal plenary session. Lesage supported the idea of sovereignty, but interdependent sovereignty, which corresponded to a special status and not sovereignty-association.

During his last years as leader, Lesage lost, one by one, his most progressive colleagues. At the party convention in October 1967, Lévesque was forced to withdraw his resolution on a sovereign Quebec within a Canadian economic union. He broke with the Liberals and sat as an independent. On 16 October the Le Devoir journalist Michel Roy wrote that, on the eve of Lévesque’s departure, the former premier wore “one of the most triumphant smiles in the entire political history of Quebec,” probably happy and relieved to see an unwelcome rival leave the stage. This event marked the beginning of the break between the province’s separatists and federalists, a split lasting into the early 21st century. These two great figures of Quebec history had traits in common: extraordinary intelligence, great eloquence, and an outstanding capacity for work. In addition, both saw their province as rich, educated, proud of its culture, a master of its economy, and open to the world. However, their social origins, working methods and, above all, political ideas divided them. Together they had been a force for mobilization and change that has rarely been seen in Quebec.

Lesage’s leadership was increasingly questioned and his authority undermined. Many aspired to his position: his long-time rival Gérin-Lajoie, mlas Laporte, Wagner, and Robert

Lawyer and administrator

His political career at an end, Lesage returned to practising law. As a legal counsel, he became a member of the legislation committee, formed the previous year by the Executive Council to take on one of the roles previously held by the abolished Legislative Council. Its mandate was to prepare, write, and review draft legislation. Lesage also advised the Quebec government on its international finance relations. As well, he joined two law firms: Lesage, Coote et Lesage in Quebec City, and Laidley, Howard, Lesage, McDougall, L’Écuyer, Graham et Stocks in Montreal, where he focused mainly on corporate and tax law. He was the legal representative of numerous companies, including the Iron Ore Company of Canada and the Quebec Iron and Titanium Corporation.

In addition, Lesage had seats on the boards of directors of several actuarial, insurance, transport, consumer-goods, and construction companies, among them Soletanche and Rodio of Canada Limited, Lever Brothers Limited, the Montreal Trust Company, Mondev International Limited, Campbell Chibougamau Mines Limited, J. J. Baker Limited, and the Canadian Reynolds Metal Company Limited. He was president of the board of the Quebec Nordiques hockey club from June 1972 until 1980. The man who had not become wealthy in politics was now a member of many organizations, and was at last able to ensure that he and his family were financially secure.

Honours

Lesage earned an impressive number of distinctions. He was presented with the Gloire de l’Escolle medal by the Laval alumni organization in 1961, and the following year the Académie Française awarded him the Prix de la Langue Française medal. Numerous universities awarded him honorary doctorates (Laval, Bishop’s, Mount Allison, Montréal, Sherbrooke, McGill, Ottawa, Toronto, Western Ontario, New Brunswick, and Moncton, as well as Dartmouth College, the Panteios School of Economic and Political Sciences, and Sir George Williams University). In 1963–65 he was honorary lieutenant-colonel of the 6th Field Artillery Regiment, RCA (also called the 6e Régiment d’Artillerie de Campagne, RCA, from 1970), and honorary colonel from 1965 to 1971. He was made a knight of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England (1966) and the Order of St Lazarus of Jerusalem (1967), and a companion of the Order of Canada (1971). The Ordre de la Pléiade honoured him with the posthumous rank of grand officer on 14 Feb. 1991.

Death and funeral

On Friday 12 Dec. 1980, Lesage died in his sleep following a heart attack at his home in Sillery. At the age of 68½, he had still been active, going to his office every day. That May, suffering from throat cancer, he had taken part in the referendum campaign in favour of the “No” vote, together with his successors as head of the Liberal Party, Bourassa and Ryan. This occasion was his last political act and his last public appearance. When his death was announced, the National Assembly (formerly the Legislative Assembly) was in session. In sharing the news, Ryan, leader of the Liberal Party and the official opposition, described Lesage as the “father of the positive affirmation of Quebec at both the federal and international level.” Parizeau, minister of finance in Lévesque’s Parti Québecois government, stated, “Mr. Lesage taught us how to work.” The government’s parliamentary leader, Claude Charron, considered him “the government leader who allowed us to be the first educated generation of Quebecers.”

The Lévesque government declared a three-day period of mourning and set a precedent by giving a former premier a state funeral, which included his lying-in-state at the Salon Rouge, the room used by the Legislative Council, thus making Lesage the first in a long tradition to receive this honour. The deceased lay in a mortuary chapel, where nearly 5,000 people paid tribute and offered condolences to the family. With Archbishop of Quebec Cardinal Maurice Roy* presiding, the religious ceremony took place at Notre-Dame basilica in Quebec City. In attendance were several well-known figures from the province and other parts of Canada as well as many ordinary citizens. The deputy premier, Jacques-Yvan Morin, stood in for Premier Lévesque, who was on an official visit to France.

Lesage’s memory is very much in evidence in place names in Quebec, first and foremost in the capital: a boulevard in Lower Town was named in his honour in 1982, as were the international airport in 1993, an office building in 1999, and a provincial electoral riding in 2003. Elsewhere in the province many streets bear his name, as does a long stretch of Autoroute 20 on the south bank of the St Lawrence (1988), the power station Centrale Manic-2 located northwest of Baie-Comeau (2010), and the head office of Hydro-Quebec in Montreal (2017). In 1998 Canada Post issued a stamp in his honour, and in 2000 a bronze statue was unveiled on the grounds of the legislative building in Quebec City.

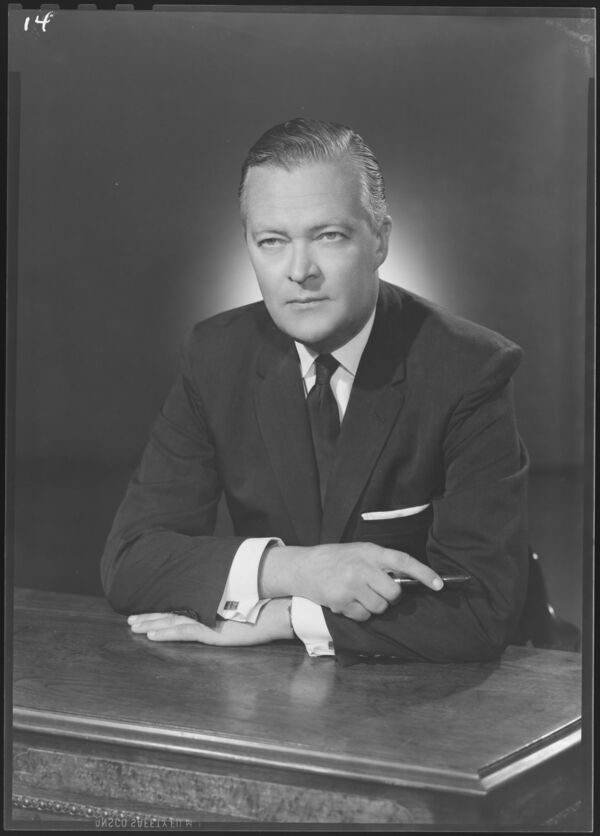

The man

Lesage had many qualities, the greatest being, in the unanimous opinion of commentators and his colleagues, his capacity for work. His workday began at 8:00 a.m., ended at about 7:30 p.m., and then continued at home until late into the night. He got through a colossal amount of work at the legislature as well as at his residence on Avenue De Bougainville, where he received colleagues, read documents, and made night-time telephone calls. René Arthur wrote in Perspectives (1970) that Lesage was “a glutton for work.” Fast and energetic, he was gifted with a prodigious memory and possessed an astonishing capacity for absorbing the most complex files. He was “guilt-inducingly punctual,” as Morin related in Mes premiers ministres. He always arrived first, whether at the office, meetings of the caucus and cabinet, or sittings of the Legislative Assembly, and he hated people to be late.

Although he had contributed to the secularization of schools and hospitals, Lesage, a devout, practising Catholic, attended daily mass at the parish church of Saint-Cœur-de-Marie, Rue Grande Allée, before going to the office. In 1961 Johnson, then an mla, told those in the assembly that in this respect Lesage showed “an exemplary attitude.” In his funeral oration, Cardinal Roy stressed that Lesage was a sincere, generous Christian.

Lesage was handsome in appearance. René Chaloult, a Union Nationale mla, a Liberal mla, and then an independent (1936–52), described him in his Mémoires politiques: “Of above-average height, elegant, with greying blond hair, he had fine, symmetrical features, and bright, twinkling eyes. A captivating smile, sometimes a bit artificial, lit up his face. He had a resounding voice. He exuded strength, stability, and health.” Women were apparently very attracted to him. In 1966 he was awarded the trophy for the handsomest man in Canada on the program Place aux femmes, broadcast on Radio-Canada. Colleagues in the assembly, adversaries, and caricaturists had a field day making fun of “the handsomest man.”

In Ne bougez plus! Gérard Bergeron wrote that the “Quiet Revolution [had been] a noisy evolution and above all … long-winded. Lesage, who [had] been its embodiment, [had] talked [about it] more than anyone. He was its natural champion.” A traditional, rather grandiloquent orator, accustomed to election campaigns, and who occasionally used theatrical language and gestures, Lesage excelled in the Legislative Assembly and easily made himself heard even without microphones and loudspeakers. His bearing was haughty. According to Maclean’s journalist Peter Charles Newman, when responding to questions in the assembly, Lesage put his hands in his jacket pockets exactly as John Fitzgerald Kennedy did. Like Lévesque, he came over well on the small screen and on radio; unlike Duplessis, he used television to his advantage. He and Lévesque were the best spokesmen for the Quiet Revolution.

As an administrator of public funds, Lesage facilitated a process of reform despite occasional initial opposition, and he generally succeeded in getting people to accept upheavals even though some ministers stood against him. He was also courageous, taking risks to introduce forward-looking measures likely to displease and damage his party.

Not without faults, Lesage was reputedly short-tempered. According to Pierre Godin’s account in the first volume of his biography of Johnson, the latter once described Lesage as “a charging bull. He is incapable of complicated strategy. With him, you’ve got to use the technique of the raging bull! You show him a red rag and he charges!” As Morin writes in Mes premiers ministres, Lesage flared up easily and often, but his outbursts were short and inconsequential. He sometimes harboured grudges and wanted to crush his adversary.

Lesage’s acquaintances and most of his biographers mention that he consumed alcohol, which he had done since his university days. In common with a good many politicians of his time, Lesage liked a drink. To obtain a favourable decision, some of his ministers would share a bottle of gin with him. Morin says that, during outings, he had to take precautions to limit Lesage’s access to liquor; in his opinion this penchant, however, never had “[any] dire effects on [his] conduct of public affairs.” Under the influence of alcohol, Lesage sometimes became aggressive. In the assembly, Unionist mlas often made malicious references to his drinking. During a cabinet meeting in February 1965, Lesage pledged to stop drinking, and for a time he kept his word. After the 1966 election, when his leadership began to be challenged, he drank more than usual.

Family life, especially when there are young children, sometimes does not fit well with politics, and the Lesage family was no exception. Corinne Lesage had sacrificed her dream of a career in classical music. During her husband’s absences, she alone ran the household and looked after their four children – Jules, René, Marie, and Raymond. She also had to play her part as first lady at official ceremonies and meetings. For her, political life “was a broken family life,” as she confided in a Le Soleil article on 23 March 2013. Fortunately, the family was able to spend the summers between 1947 and 1959 at a cottage in Berthier-sur-Mer, and they took breaks in Florida more often than they had before. Her husband, a man with only one love in his life, could nevertheless not prevent rumours about an extramarital affair.

Lesage remained loyal to his university friends. He had very strong ties with René Arthur, for example. On the political front he seemed to maintain friendships with Pearson as well as Arsenault, a colleague from Ottawa, and Jacques Miquelon, an mla and Unionist minister. Many of his friends were from legal circles, including Ross Goodwin and René Paquet.

In his leisure time, Lesage particularly enjoyed golf. A fanatical but mediocre player, he often took part in games during his annual breaks in Miami and at interprovincial conferences. Together with a group of businessmen from the Quebec City area, he was among the founders of the Club de Golf du Lac Beauport Incorporé, opened in 1962. He also spent time fishing. Every year, for example, he went trout fishing in Laurentides National Park with members of the Quebec parliamentary press corps.

Assessment

How should Lesage be judged? His inability to clarify Quebec’s constitutional status within Canada and the status of those French Canadians who had become Quebecers is certainly one of his most resounding failures. And yet the former federal minister, renowned as a centralist, showed instead that he was really more of a nationalist. He treated nationalism as he treated most other issues he negotiated: that is, he moved gradually and pragmatically. At the 1960 federal–provincial conference, he defined his thinking on his province’s “full sovereignty”: it should apply “in the areas within its jurisdiction without, however, forgetting that every [Canadian] government is subject to an inevitable interdependence.” Lesage was among the federalists who were deeply attached to a bilingual and binational Canada, and who had long wished, hoped, and waited in vain for a full recognition of Quebec in the form of a special status within the Canadian federation. On this thorny question, Lesage had to navigate between the proposals of his ministers, those of the sovereigntist movement, and those of the Union Nationale, which all strayed too far from his own convictions. Moreover, he clashed over this matter with the federal government, which could not accept a special status for the province.

The Lesage era has its detractors. The Quiet Revolution gave rise to much criticism that remains current in the 21st century and even arouses strong feelings. It is blamed for having indebted Quebec, distorted the principles of the free market, ceded power to technocrats, and destroyed Quebecers’ traditional spirit of mutual help. Others accuse those who had roles in the Quiet Revolution of having gone too far and turning the entire province upside down without always explaining their reforms.

Lesage was a great premier, one of Quebec’s greatest. In Mémoires d’un révolutionnaire tranquille, Castonguay writes that “Lesage was in my eyes a real leader, able, if need be,… to show great firmness, and he had restored to the role of premier a prestige that it had long since lost.” In Lesage s’engage, the premier defended “a policy of national greatness.” Because of his intelligence, his dedication to work and, above all, his government’s achievements, Lesage is often accorded the title of father of the Quiet Revolution. Some believe that it should go to his colleagues Lapalme, Lévesque, or Gérin-Lajoie. He was certainly “the exceptionally brilliant and masterly conductor of a suite of political, administrative, and social transformations, the like of which Quebec had never seen,” as Gérin-Lajoie puts it in Jean Lesage et l’éveil d’une nation.

Jean Lesage was the embodiment of the Quiet Revolution, of which he was the guiding spirit. Born to lead, he assembled extraordinary teams of ministers and civil servants. His cabinet more often resembled a coalition than a united government; his worth is all the greater for it. The “democratic unifier,” as François Aquin describes him in Jean Lesage et l’éveil d’une nation, recruited competent people who were able to work together despite their differences. He gave them the freedom and the means to innovate, and, when the time came, he defended their actions. Despite the limits of his achievement, he remains one of the giants of Quebec’s history.

Jean Lesage is the author of “Education of Eskimos,” Canadian Education (Toronto), 12 (1956–57), no.3: 44–48. In 1959 he published Lesage s’engage: libéralisme québécois d’aujourd’hui: jalon de doctrine (Montréal), which brought together his most important statements on five aspects of the Quebec Liberal Party’s platform. His key speeches appeared in Un Québec fort dans une nouvelle Confédération (Québec, 1965).

The Dale Cairn Thomson fonds (MG 2040), held by the McGill Univ. Arch. in Montreal, is an important source of information on Lesage. Numerous interviews with, among others, Lesage’s family members, friends, and collaborators, as well as with politicians and journalists, were examined. Also consulted were his speeches and correspondence in the Jean Lesage fonds (P688) at the Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Québec. The file on his military service, held at Library and Arch. Can., was also useful.

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Saint-Raymond, Québec, 2 juill. 1938 and St-Enfant-Jésus de Miles End, Montréal, 12 juin 1912: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 8 Sept. 2023). Musée de la Civilisation (Québec), Fonds d’arch. du séminaire de Québec, bulletins. L’Action (Québec), 19 janv., 19 mars 1970. L’Action catholique (Québec), 22 août 1935; 30, 31 mai 1958. René Arthur, “Sensible, courageux et bourreau de travail, voilà mon patron: Jean Lesage,” Perspectives (Montréal), 17 janv. 1970. Le Devoir (Montréal), 12 févr. 1937; 14 juin 1958; 7 mai 1960; 6 oct. 1961; 4 juin 1962; 17 mars 1965; 14 janv. 1966; 16 oct. 1967; 27, 28, 29 août 1970; 13 déc. 1980; 15 mars 1994; 11 déc. 1995; 17, 18 déc. 2003; 22 juin 2010. Le Journal de Québec, 14 févr. 1991. Montréal-Matin, 26 mai 1966, 28 août 1969. La Presse (Montréal), 15 sept. 1962; 10 juill., 27, 28, 29 août 1969; 13, 16 déc. 1980. Le Soleil (Québec), 3 mai 1930; 23 août 1934; 19 août 1935; 12 févr. 1937; 15 mai 1945; 15 déc. 1965; 13, 15, 16 déc. 1980; 14 févr. 1998; 17 juin 2000; 23 mars 2013. Bona Arsenault, Malgré les obstacles (Québec, s.d.); Souvenirs et confidences ([Montréal], 1983). Gérard Bergeron, Ne bougez plus!: portraits de 40 politiciens de Québec et d’Ottawa (Montréal, 1968). Gérald Bernier et Robert Boily, Le Québec en chiffres de 1850 à nos jours (Montréal, 1986). Biographies canadiennes-françaises, Raphaël Ouimet, édit. (Montréal), 1960: 14–15; 1968–69: 38–39. Conrad Black, Duplessis (Toronto, 1977). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 24 Sept. 1945; 30 March, 22 May 1950; 23 June 1951; 14 April 1954. The Canadian directory of parliament, 1867–1967, ed. J. K. Johnson (Ottawa, 1968). Mario Cardinal et al., Si l’Union nationale m’était contée … (Montréal, 1978). Claude Castonguay, Mémoires d’un révolutionnaire tranquille (Montréal, 2005). René Chaloult, Mémoires politiques (Montréal, 1969). “Le Chef de la ‘Révolution tranquille,’” Almanach moderne (Montréal), 1966: 184. J.-P. Cloutier, “Un document inédit: René Lévesque,” Amicale des Anciens Parlementaires du Québec, Bull. (Québec), 8 (hiver 2007–8), no.3: 19–23. Current biography yearbook, ed. Charles Moritz (New York), 1960. Richard Daignault, Lesage (Montréal, 1981). Peter Desbarats, René: a Canadian in search of a country (Toronto, 1976). Directeur général des élections du Québec, “Élections générales au Québec, 1867–2014,” dans Rapport des résultats officiels du scrutin: élections générales du 7 avril 2014 ([Québec], 2014), chap.7 (available at docs.electionsquebec.qc.ca/PRO/615da43f33138/DGE-6283-2014.pdf). Directory, Quebec City and Lévis, 1921–75. Dominion–provincial conference … (Ottawa, 1960). Lucia Ferretti, “Dossier: la Révolution tranquille,” L’Action nationale (Montréal), 89 (1999), no.10: 59–91. Guy Frégault, Chronique des années perdues ([Montréal], 1976). Jean Genest, “M. Albert Rioux (1899–1983),” L’Action nationale, 73 (1983): 67–71. Georges-Émile Lapalme, sous la dir. de J.-F. Léonard (Sillery [Québec], 1988). Paul Gérin-Lajoie, Combats d’un révolutionnaire tranquille: propos et confidences (Montréal, 1989). Pierre Godin, Daniel Johnson (2v., Montréal, 1980); René Lévesque (4v., Montréal, 1994–2005). Paul Gros d’Aillon, Daniel Johnson: l’égalité avant l’indépendance ([Montréal], 1979). Groupe de Recherche Sociale, Les préférences politiques des électeurs québécois en 1962 (Montréal, 1964). Historica Canada, “The Canadian encyclopedia”: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en (consulted 7 Sept. 2023). “L’Honorable Jean Lesage, chef de l’opposition,” Almanach moderne, 1967: 203–4. Jean Lesage et l’éveil d’une nation: les débuts de la Révolution tranquille, sous la dir. de Robert Comeau (Sillery, 1989). Michel Lamy, “La Révolution tranquille et le nationalisme politique: analyse du contenu des discours de Jean Lesage durant le premier mandat du gouvernement libéral (1960–1962)” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, 1994). G.-É. Lapalme, Mémoires (3v., [Montréal], 1969–73). P.-M. Lapointe, “N.D.L.R.: M. Lesage battu …,” Le Magazine Maclean (Montréal), 6 (1966), no.7: 3. Alain Lavigne, Lesage, le chef télégénique: le marketing politique de “l’équipe du tonnerre” (Québec, [2014]). J.-J. Lefebvre, “In memoriam: l’Hon. Jean Lesage (1912–1980),” La Rev. du Barreau du Québec (Montréal), 41 (1981): 356–61. J.-P. Lefebvre, Entre deux fêtes ([Montréal], 1987). Jean Lesage, Jean Lesage vous parle: les grands discours de la Révolution tranquille, Denis Monière et J.-F. Simard, édit. ([Québec], 2017). Michel Lévesque, Histoire du Parti libéral du Québec: la nébuleuse politique, 1867–1960 (Québec, [2013]); “Pour en finir avec le bon et juste Adélard Godbout,” L’Action nationale, 96 (2006), no.10: 45–52. René Lévesque, Memoirs, trans. Philip Stratford (Toronto, 1986). P.-A. Linteau et al., Quebec: a history, 1867–1929, trans. Robert Chodos (Toronto, 1983); Quebec since 1930, trans. Robert Chodos and Ellen Garmaise (Toronto, 1991). Jean Loiselle, Daniel Johnson: le Québec d’abord (Montréal, 1999). Claude Morin, Mes premiers ministres: Lesage, Johnson, Bertrand, Bourassa et Lévesque ([Montréal], 1991). P. C. Newman, “The French revolution, Quebec 1961,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 74 (1961), no.8: 20, 83–89. 1945–1960: les quinze années qui ont merveilleusement formé Jean Lesage, chef du Parti libéral du Québec (s.l., [1960?]). Pierre O’Neill et Jacques Benjamin, Les Mandarins du pouvoir: l’exercice du pouvoir au Québec de Jean Lesage à René Lévesque (Montréal, 1978). Martin Pâquet et Stéphane Savard, Brève histoire de la Révolution tranquille ([Montréal], 2021). Parl. of Can., “Parliamentarians”: lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/People/parliamentarians (consulted 17 Sept. 2020). L. B. Pearson, Mike: the memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester B. Pearson, pc, cc, om, obe, ma, lld (3v., Toronto, 1972–75). Réjean Pelletier, “La Révolution tranquille,” dans Le Québec en jeu: comprendre les grands défis, sous la dir. de Gérard Daigle et Guy Rocher (Montréal, 1992), 609–24. Plutarque LXI, “Gloire de l’Escolle,” Le Vieil Escollier de Laval (Québec), 13 (octobre 1961): 16–17. “Le premier ministre de la province de Québec et ministre des Affaires fédérales-provinciales,” Almanach Éclair (Montréal), 1962: 123. “Le premier ministre du Québec: l’Hon. Jean Lesage,” Almanach moderne, 1964: 199. Québec, Assemblée législative, Débats, 24 nov. 1959; 15 nov. 1960; 2, 7 mars, 14, 27 avril 1961; 12 avril 1962; Assemblée nationale, Débats, 12 déc. 1980; “Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1764 à nos jours”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/membres/notices/index.html (consulted 3 June 2019); “Histoire”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/patrimoine/index.html (consulted 23 June 2016); “Mémoires de députés”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/video-audio/emissions-capsules-promotionnelles/memoires-deputes/index.html (consulted 16 July 2019); Report on the general election of 1960 … (Québec, 1960); Royal commission of inquiry on education in the province of Quebec, Report (5v. in 3, [Quebec City], 1963–66), 1 (The structure of the educational system at the provincial level); Treasury Dept., Public accounts, 1959–60, 1965–67. Radio-Canada, “Archives. Quand les libéraux de Jean Lesage ont pris le pouvoir au 1960”: ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1712238/election-quebec-jean-lesage-histoire-archives (consulted 4 April 2022). La Révolution tranquille, 40 ans plus tard: un bilan, sous la dir. d’Yves Bélanger (Montréal, 2000). Jocelyn Saint-Pierre, La tribune de la presse à Québec depuis 1960 (Québec, [2016]). Michel Sarra-Bournet, Entre corporatisme et libéralisme: le patronat québécois dans l’après-guerre ([Québec], 2021). Thomas Sloan, Quebec: the not-so-quiet revolution (Toronto, 1965). Yves Théorêt et A.-A. Lafrance, Les éminences grises: à l’ombre du pouvoir (Montréal, 2006). D. C. Thomson, Jean Lesage & the Quiet Revolution (Toronto, 1984). P.-E. Trudeau, “L’homme de gauche et les élections provinciales,” Cité libre (Montréal), no.51 (novembre 1962): 3–7. Univ. Laval, Faculté de droit, Annuaire, 1934–35. J.-P. Warren, “L’origine d’un nom: d’où vient l’expression ‘Révolution tranquille’?”: histoireengagee.ca/lorigine-dun-nom-dou-vient-lexpression-revolution-tranquille (consulted 13 Dec. 2019).

Cite This Article

Jocelyn Saint-Pierre, “LESAGE, JEAN (baptized Joseph-Hertel-Jean),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lesage_jean_20E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lesage_jean_20E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jocelyn Saint-Pierre |

| Title of Article: | LESAGE, JEAN (baptized Joseph-Hertel-Jean) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 26, 2025 |