Source: Link

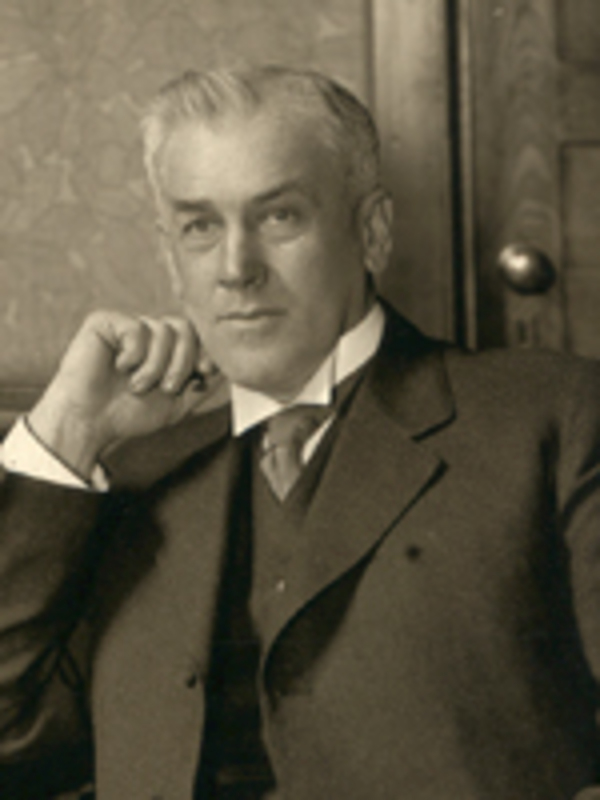

McCrimmon, Abraham Lincoln, educator and author; b. 6 March 1865 near Delhi, Norfolk County, Upper Canada, son of Daniel McCrimmon and Mary Miller; m. 15 April 1889 Florence Beatrice Anderson (1870–1922) in Port Royal, Ont., and they had two sons and one daughter; d. 16 April 1935 in Hamilton and was buried in Port Royal Cemetery.

A. Lincoln McCrimmon attended public school in Delhi and high school in Simcoe. He studied philosophy with George Paxton Young* at the University of Toronto, obtaining a ba with honours in 1890 (ma 1891). He would later undertake studies at the University of Chicago, a pioneer in the teaching of political economy and sociology. He was to receive honorary doctorates from McMaster University in Toronto (1904) and Acadia University in Wolfville, N.S. (1924).

McCrimmon was an excellent athlete in his youth, active in baseball, soccer, rugby, and cricket. He played on the varsity baseball team from 1886 to 1890, and during that time, the Toronto Evening Telegram reported, he struck out as many as 12 batters in a row and participated in 2 triple plays. It was also stated by the Simcoe Reformer that he was “one of the first exponents in Ontario of the curve ball.” He could have pursued offers to play professional baseball, but his true loves were academic life and service to his Baptist denomination.

In 1892 McCrimmon joined Woodstock College, a southwestern Ontario school run by the Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec (BCOQ), as an instructor in Latin and Greek. Four years later he was made acting principal, and in 1897 he received a permanent appointment to that post. While retaining it, in 1904 he was taken on by McMaster University (another BCOQ institution) as a part-time lecturer in political economy. He left Woodstock College in 1906 when he became a full-time faculty member at McMaster and chair of economics, education, and sociology. The Toronto Daily Star welcomed him on 15 May as “one of the foremost of Canada’s educationists.” McCrimmon’s interests, the Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto) would later report, “were more philosophic than economic,” but he was “a challenging teacher with a great capacity to make … [students] think for themselves.” His rapid rise in leadership at McMaster culminated in his succeeding Alexander Charles McKay* as chancellor in 1911, and he served in this position until stress and illness forced his resignation in 1922. He continued on at McMaster, however, as professor of Christian ethics, education, and sociology, a post he held through the removal of McMaster to Hamilton in 1930 until his death at home from a heart attack five years later.

The first part of McCrimmon’s tenure as chancellor was dominated by the home-front demands of the First World War. His addresses at this time were patriotic endorsements of the war effort in defence of justice and the British empire, and he actively championed the implementation of conscription by the Union government of Sir Robert Laird Borden in 1917. In the face of rising anti-German sentiment in Canada, he successfully resisted efforts to have a German professor dismissed from the university. The war placed unprecedented economic and social pressures on all institutions, and McMaster did not escape them. It fell to McCrimmon to deal with the ensuing staff shortages – he was obliged to take on much of the teaching in political science and sociology himself – and to cope with the lack of funds resulting from declining student enrolment. While every chancellor since the university’s founding [see William McMaster*] had contended with financial difficulties, “perhaps at no time,” the McMaster Graduate commented in 1922, “was the handling of them so exhausting as during the war period and the subsequent years of reconstruction.”

These difficulties were compounded in the immediate post-war era by theological turmoil. The conflict was one of long standing. Elmore Harris, pastor emeritus at Walmer Road Baptist Church in Toronto, had led the charge in 1908 that theological liberalism had crept into the McMaster program and that the fundamentals of the faith were being eroded [see William James McKay*]. Although such claims were subsiding by the time McCrimmon became chancellor, they were revived in 1919 by Thomas Todhunter Shields*, pastor of Jarvis Street Baptist. McCrimmon had to face the oft-raucous debates in the BCOQ over doctrine at the university. It was this issue, combined with the demands of the war and the sudden death of his wife in 1922, that most likely broke his health.

McCrimmon’s pedagogical stance, expressed in The educational policy of the Baptists of Ontario and Quebec (Toronto, 1920), was a fusion of Christian instruction in morals and doctrine, academic excellence, and nation building. His approach has been described by historian George Alexander Rawlyk* as a “potent mix” of innovation and orthodoxy, and he sought to steer McMaster safely between the Scylla of modernism and the Charybdis of fundamentalism. To counter secularizing influences, he advocated continued denominational control of the university, and to this end he exhorted the BCOQ, which expected McMaster to be self-supporting, to come to its aid financially.

In his one major written work, The woman movement (Philadelphia and Toronto, 1915), McCrimmon surveyed the rights and roles of women from antiquity to the present. He was critical of the way women had been mistreated over the centuries by various societies (including those of Christendom) and urged that they should have equal educational opportunities. While he stressed the maternal aspects of their physiology, McCrimmon also supported new societal roles for women and championed their right to vote. The BCOQ would be one of the first Canadian bodies to ordain women (1947), and works such as The woman movement helped prepare the denomination for such a decision.

McCrimmon identified closely with his denomination and took on positions of leadership in its organizations. He served as vice-president of the General Convention of Baptists of North America in 1907–11 and as president in 1911–17. He was elected president of the BCOQ for three terms: 1921–22, 1930–31, and 1931–32. The acting chairman of the executive committee of the Baptist World Alliance (BWA) at its 1934 congress in Berlin, he was one of only two Canadians to deliver major addresses there. These positions brought him and his university both prestige and an international profile. In 1908–9 he had been vice-president of the Moral and Social Reform League of Toronto, a local branch of the Moral and Social Reform Council of Ontario.

At the university memorial service following McCrimmon’s death, McMaster chancellor Howard Primrose Whidden* and John James MacNeill, principal of the faculty of theology, spoke highly of his contributions to academic and denominational life. Regarding his religious legacy, one Baptist paper declared, “Probably no other man in our denomination has had so great an influence, over so long a period, on as great a number of our present missionaries on both the Home and Foreign fields.” As far as his institutional legacy is concerned, however, he ultimately failed in his goal of keeping McMaster under Baptist control: in 1957 it became a non-denominational provincial body. Perhaps McCrimmon’s greatest achievement at the university was to have guided it successfully through the tumultuous war years.

In addition to the works mentioned in the text, Abraham Lincoln McCrimmon is the author of Baptists and Christian union (Toronto, n.d.), Baptists and denominationalism (Toronto, n.d.), The child in the normal home (Philadelphia, [1910]), and The birth status of a child … (Toronto, 1925).

There is no published life of McCrimmon. This biography is based on the Abraham Lincoln McCrimmon box in the Canadian Baptist Arch., located at McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ont., which contains files, newspaper clippings, originals or copies of documents, and sermon notes. Additional sources include: Canadian Baptist Arch., Chancellor’s corr., 1911–22; C. M. Johnston and J. G. Greenlee, McMaster University (3v. to date, Toronto and Montreal, 1976– ), 1, 2; and G. A. Rawlyk, “A. L. McCrimmon, H. P. Whidden, T. T. Shields, Christian education, and McMaster University,” in Canadian Baptists and Christian higher education, ed. G. A. Rawlyk (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1988), 31–62.

Canadian Baptist (Toronto), 1911–35. “Abraham Lincoln McCrimmon,” Link and Visitor (Toronto), June 1935: 7–8. Robert Wright, A world mission: Canadian Protestantism and the quest for a new international order, 1918–1939 (Montreal and Kingston, 1991).

Cite This Article

Gordon L. Heath, “MCCRIMMON, ABRAHAM LINCOLN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccrimmon_abraham_lincoln_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccrimmon_abraham_lincoln_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gordon L. Heath |

| Title of Article: | MCCRIMMON, ABRAHAM LINCOLN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |