Source: Link

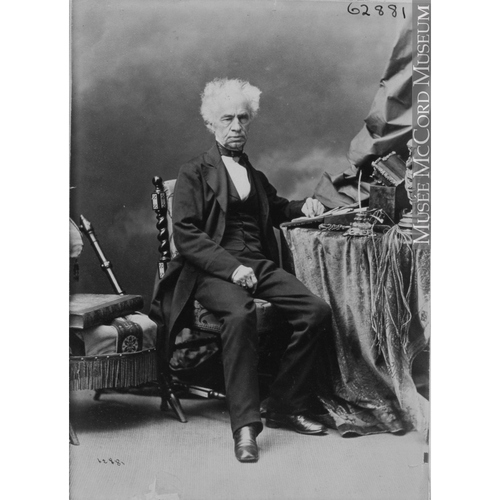

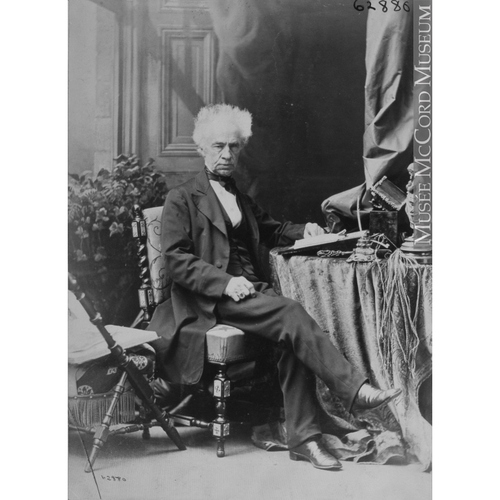

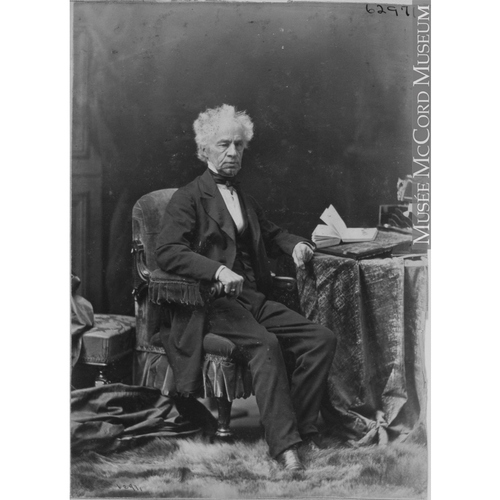

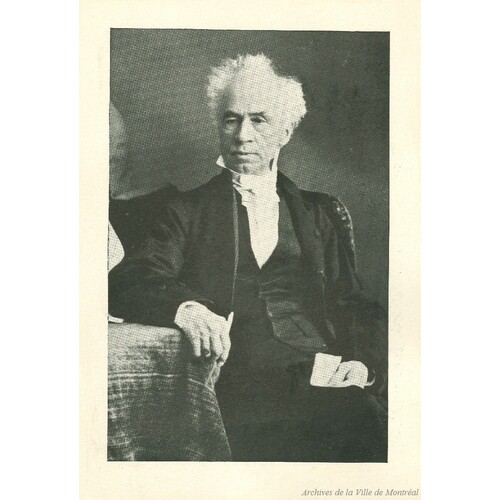

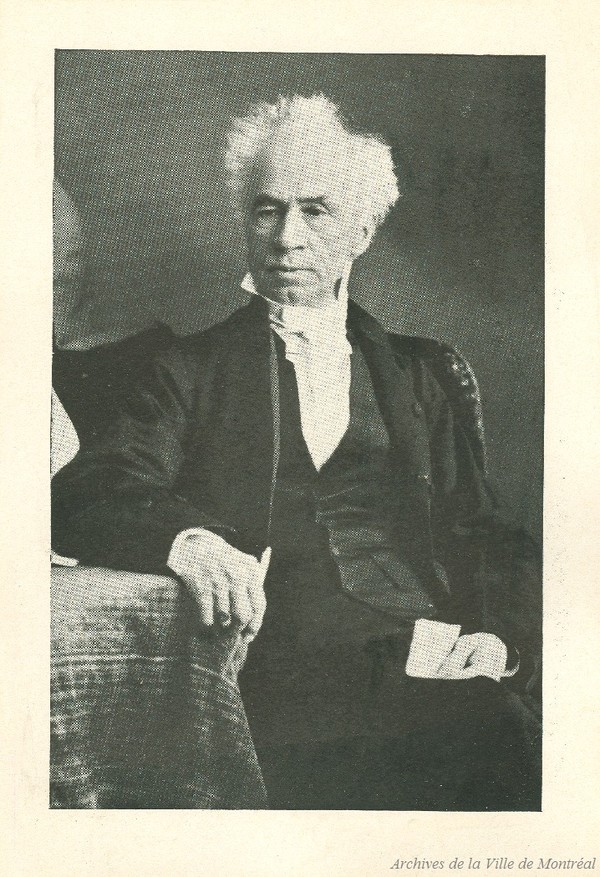

MONDELET, CHARLES (baptized Joseph-Charles-Elzéar), lawyer and judge; b. 28 Dec. 1801 in the parish of Saint-Marc, county of Verchères, L.C., son of Charlotte Grosbois and Jean-Marie Mondelêt*, notary, member of the Legislative Assembly from 1804 to 1809, and coroner of Montreal; d. 31 Dec. 1876 at Montreal and was buried there 4 Jan. 1877.

Charles Mondelet attended the Séminaire de Nicolet and the Petit Séminaire de Montreal, and then studied law under the distinguished Michael O’Sullivan* and under Lower Canada’s attorney general, Charles Marshall. He was admitted to the bar of Lower Canada on 30 Dec. 1822 and practised first in Trois-Rivières. On 21 June 1824, in Montreal’s Christ Church Cathedral (Church of England), Charles married Elizabeth Carter. The Mondelets had 15 children; six reached adulthood.

In Trois-Rivières Mondelet immediately flung himself into the pro-assembly anti-administration politics of the period of Governor General Dalhousie [Ramsay*], which were at their most passionate in the years immediately after the 1822 union bill scare. Mondelet began with journalism, editing Ludger Duvernay*’s political and literary newspaper Le Constitutionnel, “the French gazette of Trois-Rivières,” from its foundation in 1823 until 1825 when it was discontinued. In 1826 Mondelet founded the lively and more incisive L’Argus, “journal électorique,” which was designed primarily to influence the electorate to choose radical members of parliament. Specifically, L’Argus supported the unsuccessful candidature of Pierre-Benjamin Dumoulin* against Solicitor General Charles Richard Ogden*, and then ceased to appear until it was revived a year later in Montreal by Augustin-Norbert Morin*. Mondelet was also active in a local constitutional committee which, in association with committees in other districts, had been formed to oppose union with Upper Canada and which also protested against the policies of the governor and his legislative councillors generally. These activities cost Mondelet his militia commission in November 1827. His subsequent condemnation of Governor Dalhousie’s militia policies in the Quebec Gazette earned him an indictment for libel in March 1828. After Dalhousie left Canada these charges were dropped.

In 1829 or 1830 Mondelet moved to Montreal. There he practised law with his brother Dominique* and worked for the latter’s election to the assembly in April 1831. Under the signature “Pensez-Y-Bien” he also wrote letters to the editor of La Minerve demanding that the Legislative Council be abolished or made elective. The council declared this statement libellous and imprisoned the publisher, Ludger Duvernay, for about a month. Soon after Duvernay’s release, Charles’ close association with the Patriote party ended temporarily when personal loyalties and other circumstances persuaded him tacitly to renounce his political radicalism and to defend his brother’s different politics.

In an 1832 by-election the Mondelets favoured the moderate candidate Stanley Bagg over his radical opponent Daniel Tracey*. The Patriote party condemned the brothers for their support, and even more for avoiding the inquest after troops transformed the polling into the notorious “Massacre of Montreal” by killing three of Tracey’s supporters. The Mondelets did wear mourning arm bands but their father, Jean-Marie, was after all the coroner and therefore deeply involved in the proceedings as a non-partisan official. Then on 27 Nov. 1832 the Reform-dominated assembly censured Dominique for becoming an honorary executive councillor, and the censure extended to the brother who supported him. Finally, in April 1834, when Charles publicly opposed the 92 Resolutions, Louis-Joseph Papineau’s young lieutenant Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* viciously attacked both brothers in Les deux girouettes, ou l’hypocrisie démasquée. He accused Charles of slavishly following Dominique in betraying his ideals and his party and added charges of personal hypocrisy and meanness.

Charles Mondelet nevertheless continued in close association with both moderate and radical politicians through the Comité Sanitaire de Montréal, in which he was active during the cholera years. He also joined the politico-literary club Aide-toi, le Ciel t’aidera, whose radical members later transformed it into the militant Fils de la Liberté, which in its turn gave rise to the nationalistic Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. On 2 Nov. 1837 he was unanimously accepted into the revolutionary Comité Central et Permanent du district de Montréal.

At the Montreal assizes in September 1838 Mondelet and two colleagues defended four Patriotes, François Nicolas, Amable Daunais, Joseph Pinsonnault, and Gédéon Pinsonnault, for executing loyalist Joseph Armand, dit Chartrand; the trial was noted for Charles’ impassioned speech on behalf of Nicolas. In 1839 Charles defended François Jalbert, who was accused of killing Lieutenant George Weir while he was a prisoner in Patriote custody. In both cases Mondelet argued that his clients had committed political, not criminal, acts and should therefore be treated as political prisoners: he even tried to have Jalbert freed under the amnesty granted by Lord Durham [Lambton*] on 28 June 1838. Mondelet also argued that an oppressed people should not suffer for acts committed during justifiable rebellions. In both cases the jury acquitted the prisoners. Ironically, Nicolas and the 20-year-old Daunais were later retried for their activities during the 1838 uprisings, with Dominique Mondelet one of the crown prosecutors, and they were sentenced to hang.

Between assizes, on 4 Nov. 1838, Charles Mondelet was arbitrarily arrested and thrown into the prison of Montreal, where he renewed his friendship with La Fontaine. When they were finally released without trial, Mondelet returned to his law practice until his partner and brother Dominique was appointed to the Trois-Rivières Court of Queen’s Bench on 1 June 1842. Then Charles practised briefly with his frequent legal associate Côme-Séraphin Cherrier*, Louis-Joseph Papineau’s cousin.

After the rebellions Charles, who supported Union, had mingled with politicians but not politics, devoting himself to law and to education. His farsighted Letters on elementary and practical education greatly influenced the education act of 18 Sept. 1841 introduced by Lord Sydenham [Thomson*]. Mondelet proposed English and French public schools for the united province, financed by direct taxes and legislative grants. The system would be headed by a powerful superintendent, officials appointed by the governor but responsible to the legislature, several elected officials, and all resident clergymen as ex officio school wardens. Thus in the control of public education there would be a nice balance between the people, the government, and the religious establishments. Mondelet’s description of the almost autocratic powers of the proposed superintendent of education is interesting because Sydenham promised him the post. The latter died without a commission having been issued; it may be that either the governor or Mondelet changed his mind.

Sydenham’s successor, Sir Charles Bagot*, appointed Jean-Baptiste Meilleur deputy superintendent for education in Lower Canada and named Mondelet to the district bench instead, with a jurisdiction including the counties of Terrebonne, L’Assomption, and Berthier. In 1844 he became circuit judge at Montreal. On 24 Dec. 1849 he was appointed judge of the Superior Court and served until 1859 and from 1869 until his death. From 30 May 1859 to 31 Dec. 1869 he was judge pro tem. of the Court of Queen’s Bench. It was as superior court judge that Mondelet became involved in the famous Guibord affair.

The battle raging between Quebec’s clerical hierarchy and the politically radical Institut Canadien, whose 1868 and 1869 annuals were on the Papal index, culminated in a local parish’s refusal to bury Institut member Joseph Guibord*, dit Archambault [see Truteau]. In November 1869 in his decision on the suit brought against the parish of Notre-Dame by Guibord’s widow, Henriette Brown, and later by her heir, the Institut, Judge Charles Mondelet instructed the parish to bury Guibord and to pay all court costs. This decision, reversed on 12 Sept. 1870 by the Court of Revision, was sustained on 21 Nov. 1874 by the paramount judicial authority, the Privy Council. Mondelet’s judgement was of great significance because of the issues involved: his selection of the custom of Paris as the relevant body of law and his interpretation of essentially ecclesiastical questions in defiance of contemporary ecclesiastical opinion. On 16 Nov. 1875 Guibord was buried, but Bishop Ignace Bourget* declared his plot morally separate from the Catholic cemetery, and so it has remained. Thus the spirit of Mondelet’s judgement was defied by the ecclesiastical authorities he had challenged.

Mondelet’s Essai analytique sur Le Paradis perdu de Milton (1848), co-authored with William Vondenvelden*, and his Address before the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1857), indicate his diversified interests. He even translated Peter Parley’s Geography and adapted it for use in Canadian schools, adding a supplement for small children to explain the operation of natural phenomena.

Mondelet, very much a free thinker, married an English Canadian in an Anglican church, despite his French Canadian Catholic background, and defied not only his bishop but public opinion in the Guibord affair. A witty man, he was learned in the law and also in various aspects of education, its practical operation in many countries and its philosophy. In politics he was a radical, except for one brief period, and it was these sympathies which dominated when he became a member of Aide-toi, le Ciel t’aidera, when he joined the revolutionary Comité Central et Permanent du district de Montréal, and when he defended Patriote prisoners. Immediately after 1834 Charles continued his close association with many of the radical politicians, and his youthful radicalism remained intact, for in the Guibord affair he sided with the most radical members of French Canadian society when he himself was an old man.

[Mondelet’s Letters on elementary and practical education (Montreal, 1841) gives his ideas on how a school system should be set up. Documents relating to constitutional history, 1819–1828 (Doughty and Story) contains many extracts from the official correspondence relating to the decommissioning of the militia under Dalhousie and to the libel suits of that period. L.-H. La Fontaine, Les deux girouettes; ou l’hypocrisie démasquée (Montréal, 1834) is of great importance for anyone interested in the Mondelet brothers since the entire book is devoted to attacking them. Much of the available information about Charles’ early political life in Montreal comes from this book. Christie, History of Lower Canada, III–V, and H. T. Manning, The revolt of French Canada, 1800–1835: a chapter in the history of the British commonwealth (Toronto, 1962), provide excellent surveys of the early period of Mondelet’s life. Théophile Hudon’s study of L’Institut canadien de Montréal et l’affaire Guibord; une page d’histoire (Montréal, 1938) is essential for an understanding of the intricacies of the situation, religious as well as legal. Hudon is prejudiced against Mondelet because of the latter’s anti-clericalism; still, the book is an excellent account of the Guibord case. P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la province de Québec, 379; F.-J. Audet, “Les Mondelet,” Cahiers des Dix, III (1938), 191–216; L.-P. Audet, “Charles Mondelet et l’éducation,” RSCT, 3rd ser., LI (1957) sect.i, 1–27; Gérard Malchelosse, “Généalogie de la famille Mondelet,” BRH, LI (1945), 51–60, are factual notices of Charles Mondelet and his family and provide the bulk of the secondary material on Charles. e.n.]

Archives paroissiales de Saint-Marc (comté de Verchères, Québec), Registres des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 28 Dec. 1801. BNQ, Société historique de Montréal, Collection La Fontaine, Lettres, 18, 215, 405, 554. Christ Church Cathedral (Montreal), Register of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 21 June 1824. P.-J.-O. Chauveau, L’instruction publique au Canada, précis historique et statistique (Québec, 1876). Report of the state trials before a general court martial held at Montreal in 1838–9, exhibiting a complete history of the late rebellion in Lower Canada (2v., Montreal, 1839). Beaulieu et Hamelin, Journaux du Québec. Chapais, Histoire du Canada. David, Patriotes. L.-P. Audet, Jean-Baptiste Meilleur était-il un candidat valable au poste de surintendant de l’Éducation pour le Bas-Canada en 1842?” Cahiers des Dix, XXXI (1966), 163–201. Bernard Dufebvre, “Ludger Duvernay et « La Minerve », 1827–1837,” RUL, VII (1952–53), 220–29. Victor Morin, “Clubs et sociétés notoires d’autrefois,” Cahiers des Dix, XV (1950), 185–218.

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. du Vieux-Montréal, CE601-S22, 29 janv. 1798; CE601-S51, 4 janv. 1877. La Minerve (Montréal), 23 nov. 1874, 17 nov. 1875.

Cite This Article

Elizabeth Nish, “MONDELET, CHARLES (baptized Joseph-Charles-Elzéar),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mondelet_charles_elzear_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mondelet_charles_elzear_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elizabeth Nish |

| Title of Article: | MONDELET, CHARLES (baptized Joseph-Charles-Elzéar) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |