Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

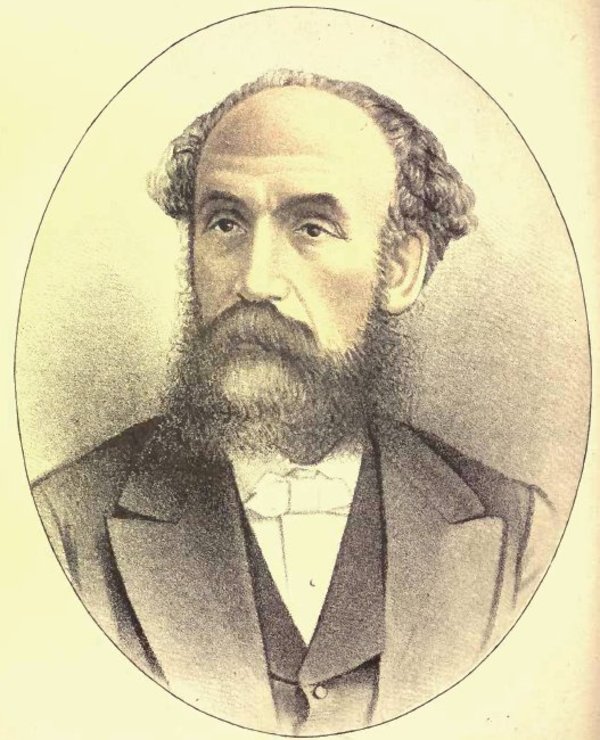

NELLES, SAMUEL SOBIESKI, Methodist minister and educator; b. 17 Oct. 1823 at Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada, eldest son of William Nelles and Mary Hardy; m. 3 July 1851 Mary Bakewell, daughter of the Reverend Enoch Wood, and they had six children; d. 17 Oct. 1887 at Cobourg, Ont.

Samuel Sobieski Nelles’ parents immigrated to Upper Canada from New York State after the War of 1812. Samuel was educated in local schools before attending Lewiston and Frederica academies in New York State and the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, N.Y. From 1842 to 1844 he was a member of the first undergraduate class at Victoria College in Cobourg, and he graduated from Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn., in 1846. After a year as principal of the Newburgh Academy in Lennox County, Canada West, he entered the ministry, serving on probation at Port Hope and Toronto. Ordained a minister of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada in 1850, he was appointed professor of classics and acting principal of Victoria College in the same year. In 1851 he became principal and in 1854, succeeding his mentor and friend Egerton Ryerson, he was appointed president. He continued as president until 1884 when the college was renamed Victoria University, and then served as its chancellor and president until 1887.

Nelles was consistently active as a Methodist minister but his most important contribution was made to Victoria College. His role as its second founder and as the principal architect of its formative period was played amidst discouraging and challenging circumstances. Victoria College had been founded in 1841 as an outgrowth of Upper Canada Academy, a Methodist preparatory school chartered in 1836. The objective of Victoria’s founders, including Anson Green* as well as John* and William Ryerson*, was not to establish a theological seminary; rather they believed that the academy would benefit “were it invested with the style and privileges of a College, and endowed by the liberality of the Legislature.” The Wesleyan Methodist Conference, however, was not fully committed to the support of higher education. Thus the determined efforts of the administration of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Robert Baldwin* to consolidate and secularize the emerging university system in 1849–50, in combination with the modest circumstances of the Methodists, nourished a mood of acute uncertainty about Victoria.

Although under the direction of Nelles the college became well established, its financial position remained precarious, a circumstance in itself symbolic of the continuing, if intermittent, controversy between the advocates of one provincial university and the supporters of denominational institutions. In this conflict Methodists were often ranged against their own brethren as well as members of other churches. Nelles, like his contemporaries who headed the other denominational colleges in the province, fought an unending battle to secure government grants and to accumulate an endowment. The former were eliminated in 1868 and a campaign to raise funds was begun by William Morley Punshon; a decade later the amount lost had been replaced by investment income. In reality, however, only strict economy and the continuing use of inadequate facilities enabled Victoria to survive. Nelles and his contemporaries were also confronted with a more formidable issue, that of responding constructively to the intellectual revolution which was being shaped by the writings of Charles Darwin and by the renewal of biblical scholarship.

Nelles was a quiet and cautious man as well as a succinct speaker and writer whose beliefs and objectives must be distilled from his actions and occasional utterances. As a Methodist minister, he was committed to an evangelical Christianity which relied heavily on religious experience and accepted John Wesley’s amalgam of conservative theology and zeal for holiness in this life. As a scholar, Nelles believed his primary function was to demonstrate that “a properly conducted inquiry into the world of nature, whether natural or human, would reveal the wondrous handiwork of God,” and thereby preserve the moral tradition of Canadian culture from the corrosion of the critical intellect.

From the outset, however, the distinctive feature of his outlook as Christian and academic was his tolerance and his receptiveness to the changing climate of opinion. In 1853 he emphasized that “Christianity itself brings happiness to men only in so far as it rectifies their disordered natures and brings . . . light to the understanding.” But the gospel could not be fully understood without intellectual preparation. He stressed that “we are not called to choose between study and prayer. Study without prayer is arrogance, prayer without study is fanaticism; and neither arrogance nor fanaticism will find true wisdom.” In his last years he was to remark that the “picture of Greece with the New Testament in her hands, may be taken . . . as an appropriate symbol of a true University. Greece . . . in a word, all human culture on its secular side. The New Testament . . . human development and perfection on its spiritual or divine side.” The sciences and history “throw floods of light, and sometimes very perplexing cross-lights, upon the works and ways of God; and they have become a necessary study.”

Such convictions led Nelles to give the writings of the Scottish “common sense” philosophers a central place in Victoria’s curriculum, to promote specialization in order that the students learn “some few things well,” and to encourage the study of the sciences and theology. In 1877 Faraday Hall, the first science building in the province, was opened at Victoria, the pride of Dr Eugene Emil Felix Richard Haanel, one of the first European scientists to teach in Canada. Cautiously, Nelles sought instructors for the college “who, while possessed of a true love of learning . . . still adhere to the faith of Christ. . . . Such men, too, are less likely to teach for science what is yet only in the region of conjecture.” In 1873 he was instrumental in establishing a faculty of theology at Victoria, thus making formal provision for the education of Methodist ministers. Significantly, its first dean was Nelles’ colleague, Nathanael Burwash*, who from the outset endeavoured to reconcile Christian theology and the advances of science and introduced his students to the new methods of biblical scholarship. Nelles’ concern for the quality of education in Victoria was matched by his determination that the college should use its full powers as a university. Hence, in addition to faculties of arts and theology, Victoria established faculties of medicine [see John Rolph*] and law in 1854 and 1862 respectively. Although these had a rather peripheral relationship with the college, their numerous graduates were very influential in the professions.

In 1887 the university had 697 students; 180 were in arts with 32 graduating (in 1854 there had been only 2 graduates). Nelles and his colleagues always recognized, however, that Victoria’s position was uncertain. Thus, from the outset he was receptive to proposals for the consolidation of the various denominational colleges with the University of Toronto into one provincial university. His mature views on this subject were enunciated in his 1885 convocation address. Recognizing that the growth of the sciences and other disciplines had created an entirely new context, he commented on the need for “a place where all sound means of discipline can be employed, and all forms of knowledge cultivated, with the best facilities of the age.” Every sect could not have a “genuine University” and the government could not “recognize the claims of one sect over another.” The solution was to establish one national university. “But such a University for a Christian people should somehow employ . . . the power of the Christian faith.” Federation appeared to offer the opportunity to give “a more positive Christian character to our higher education.” Nelles emphasized that it was painful for him to contemplate federation for an institution to which he had given his “life’s best energies,” but he would support a scheme which would lead to the “liberal and Christian reconstruction of our Provincial University.”

The act of federation was passed in April 1887, six months before his death, although its implementation would be delayed until November 1890 [see William Gooderham Jr]. At the general conference of the Methodist Church in 1886 Nelles had voted against acceptance of the proposed agreement, not because he had altered his stand but because he believed the terms would not assure Victoria’s continuance as an institution for the “work of liberal Christian training of both laity and ministers.” It was largely his stubborn insistence on and careful advocacy of these principles which ensured for Victoria and other federating institutions a well-defined role in the university curriculum and the authority to control the life and conduct of their students. Above all, he recognized that Victoria needed additional endowment income to maintain the quality of its staff and its facilities, and sought valiantly but with little success to collect such funds. His intense anxiety to serve the ends of Victoria and the Methodist community, as well as his prophetic awareness of the dilemma posed by the prospect of decay at Cobourg and of ultimate absorption in the University of Toronto undoubtedly contributed to his final illness.

The death of Nelles was marked by an immense outpouring of grief and respect from the students, alumni, and faculty of Victoria University, as well as from the Methodist Church and the citizens of Ontario. He had been honoured with a dd by Queen’s College in 1860 and an lld by Victoria in 1873. Although he held no high office in the church, he had been a delegate to other conferences on numerous occasions. He also served as president of the Ontario Teachers’ Association in 1869 and 1870. He left no body of scholarly work, other than occasional sermons, addresses at convocations, and letters. His legacy consisted in large part of the students in whom he had inspired “an honest love of the truth,” a measure of tolerance, and a concern for continuity between old beliefs and new knowledge. Victoria University would bring into federation a small but well-qualified staff, a body of loyal graduates, and an intellectual outlook deeply suffused with the Christian tradition, receptive to the claims of the sciences and of critical scholarship, and anxious to relate higher education to the needs of society. As a minister, Nelles earned deep respect and affection not as an orator but as one who enabled others to discover new insights. As a man, he was thoughtful, witty, fatherly in his dealings with students, and devoted to his children. His last message to the undergraduates was “Give the boys my love. . . .” His conference would testify that “the entire Church mourns the loss of so faithful a servant, so gifted a preacher, and so eminent a teacher.”

Victoria Univ. Arch. (Toronto), Board of Regents, Minutes, 1884–89; Victoria College Board, Minutes, 1857–84. Victoria Univ. Library (Toronto), Nathanael Burwash papers; Samuel S. Nelles papers. Acta Victoriana (Cobourg, Ont.), 1 (1878–79)–11 (1887–88). Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland, Bermuda), Bay of Quinte Conference, Minutes (Toronto), 1884; 1888. Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada, Minutes (Toronto), 1850; 1851; 1855. Christian Guardian, 1850–87. Canadian biog. dict., I: 85–87. Cornish, Cyclopædia of Methodism. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1888), 363–64. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, III: 45–47. Nathanael Burwash, The history of Victoria College (Toronto, 1927). A. B. McKillop, “A disciplined intelligence: intellectual enquiry and the moral imperative in Anglo-Canadian thought, 1850–1890” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1976); published under the title A disciplined intelligence: critical inquiry and Canadian thought in the Victorian era (Montreal, 1979). Hilda Neatby, Queen’s University: to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield, ed. F. W. Gibson and Roger Graham (1v. to date, Montreal, 1978– ). C. B. Sissons, A history of Victoria University (Toronto, 1952). R. J. Taylor, “The Darwinian revolution: the responses of four Canadian scholars”

Cite This Article

G. S. French, “NELLES, SAMUEL SOBIESKI,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelles_samuel_sobieski_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelles_samuel_sobieski_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. S. French |

| Title of Article: | NELLES, SAMUEL SOBIESKI |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | July 14, 2025 |