Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

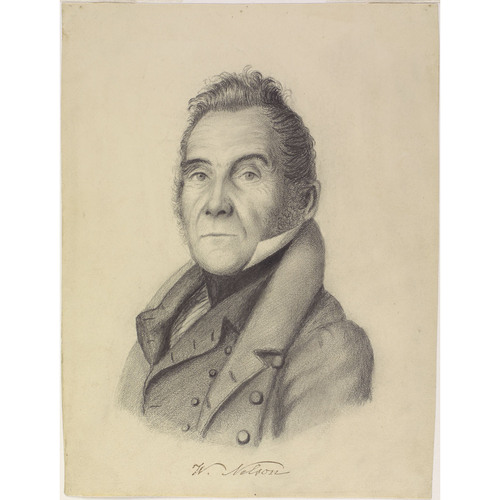

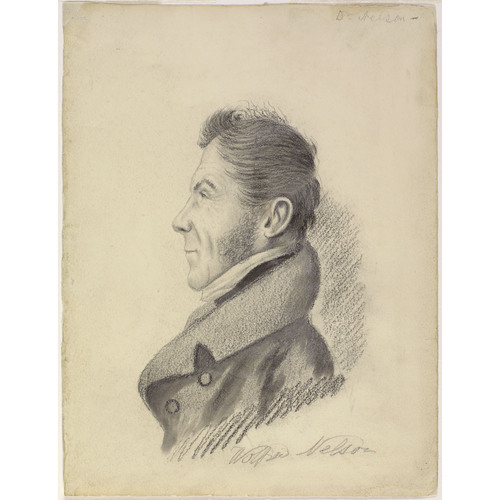

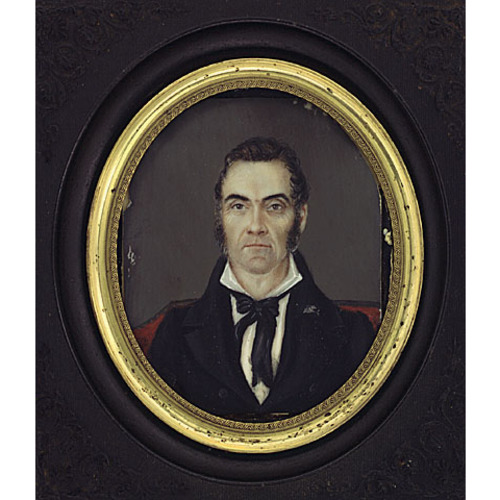

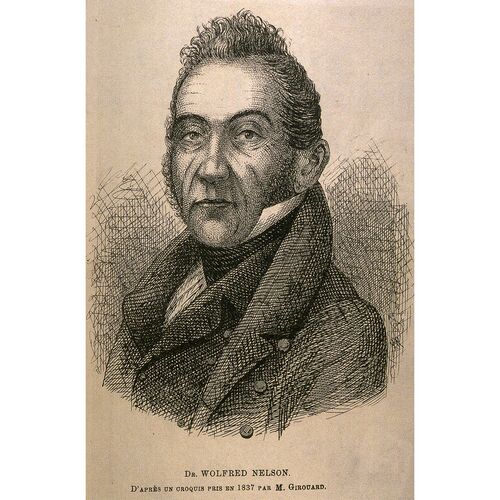

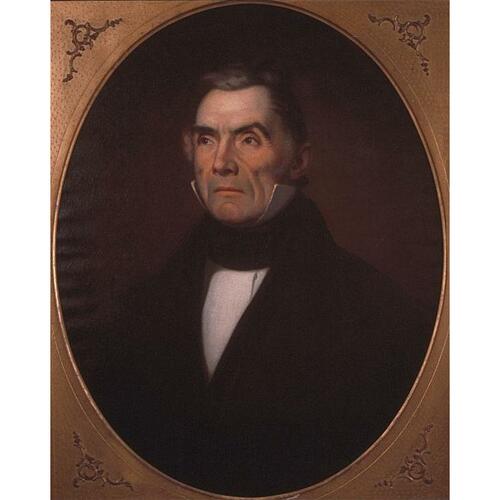

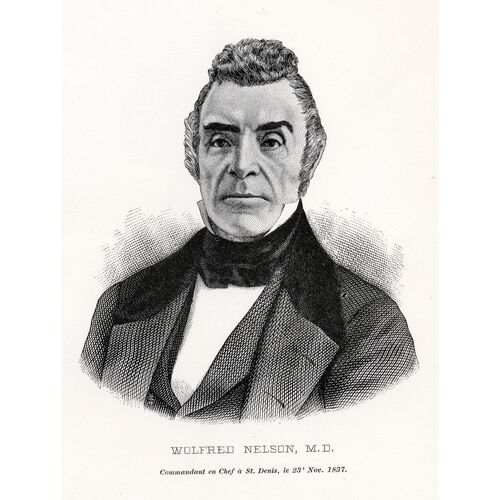

NELSON, WOLFRED, doctor, politician, and Patriote; b. 10 July 1791 in Montreal, third son of William Nelson and Jane Dies; m. in 1819 Charlotte-Josephte Noyelle de Fleurimont, and they had seven children; d. 17 June 1863 in Montreal.

There is little in Wolfred Nelson’s family background or early life to suggest that he would become an opponent of British misrule in Canada and a champion of the civil rights of French Canadians. His mother was the daughter of a wealthy New York landowner who had lost his possessions by remaining loyal to the crown during the American revolution. Wolfred’s father, a London-trained schoolmaster, had come to the Province of Quebec in 1781 and earned so high a reputation as a teacher that the British colonial authorities granted him a comfortable annual salary as an inducement for him to stay in the colony. When Wolfred was three the family moved to Sorel (officially named William-Henry although commonly called Sorel) where his father opened a school. There, in the stockaded British outpost at the mouth of the Richelieu River, he grew up. The family lived not far from the summer residence of British governors and Wolfred attended his father’s school along with the sons of British officers.

At age 14 Wolfred Nelson was apprenticed to Dr C. Carter of the British army and in February 1811 he received his surgeon’s licence. He remained in Sorel, suffering, in the words of a biographer, “the drudgery of a small military hospital” while hoping for advancement in the service. In January 1812 he learned that he was to be recommended as a hospital mate by the staff surgeon at Sorel, and a few weeks later his prospects for a military medical career were further brightened when Britain and the United States declared war. Nelson immediately petitioned Governor Sir George Prevost* for a commission and received an appointment as surgeon of the 5th battalion of embodied militia. This was a turning point in his life, although not in the expected direction. Until the War of 1812 Nelson’s world had been that of Sorel’s British élite – however humble that élite may have been – and its prejudices were his prejudices. “I was in my earliest days,” Nelson recounted many years later, “a hot Tory and inclined to detest all that was Catholic and French Canadian, but a more intimate knowledge of these people changed my views.” This intimacy began with his militia appointment. The headquarters of the battalion was at Saint-Denis, a prosperous French Canadian town of about 500 people several miles south of Sorel on the Richelieu River. In September 1813 when the battalion was called out to guard against an expected American attack, Nelson was its only English speaking officer. Following the war he established a practice at Saint-Denis.

Nelson’s political conversion from Tory to Reformer had also begun, and in 1827 he entered politics. It was a dramatic entry, for he chose to run for the assembly in the “royal borough” of William-Henry which included his home town of Sorel and which traditionally had been the fief of the governor. In the campaign he revealed himself to be an implacable enemy of the established order. His opponent, James Stuart*, the attorney general of Lower Canada, was publicly supported by Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*]. At one meeting Nelson interrupted Dalhousie, who was speaking on Stuart’s behalf, informed him that his conduct was unconstitutional, and forced him to cease his activities in the campaign. Nelson won the election by two votes, “to the astonishment and indignation of the respectable part of the inhabitants,” according to the Montreal Gazette. An outraged Stuart then began a series of harassing legal actions to annul the election. Instead, the corrupt election practices which were exposed led to Stuart’s dismissal from the office of attorney general in 1831. “The Laws,” wrote Nelson, “must be observed as much by those who govern as by those who are governed.”

For reasons not now entirely clear – perhaps simply the difficulty of attending to his duties as a doctor while serving in the assembly – Nelson did not stand for re-election in 1830. The seven years that followed were perhaps his most successful. He visited Great Britain and the Continent to study medical institutions, established a large distillery at Saint-Denis, and was appointed a justice of the peace. His political views, however, did not soften with his material success. If anything, he became increasingly radical as the abuses of the governing oligarchy became more apparent. The assassination of his friend and political ally, Louis Marcoux, during the election of 1834 at Sorel, and the subsequent acquittal of the accused murderer by a packed jury in Montreal, particularly incensed him. In an interview in January 1836 with Governor Lord Gosford [Acheson*], in which Nelson protested against the abuses by the Executive Council, Nelson warned that “if the Habitans were left to themselves and if their leaders were insulted or abused in Montreal, that would be the signal of a war of extermination.”

Indeed the conflict between the Patriote and constitutional parties, which saw French Canadians mostly on one side and English speaking – with a number of exceptions such as Nelson – on the other, was soon intensified from a war of words – editorials, speeches, and resolutions – to one of guns. In both contests Nelson fought in the front rank. In May 1837 he organized the first of many “anti-coercion meetings” held in the province that summer and proposed its first resolution which condemned the undemocratic measures recently advanced by Lord John Russell to resolve the troublesome political situation in Lower Canada. For his part in the meeting Nelson was relieved of his commission as magistrate. In October he was made chairman of the Assemblée des Six Comtés, where he again proposed the first angry resolution: “whenever any form of government becomes destructive . . . it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it.” On 16 Nov. 1837 the government moved against the Patriotes by issuing illegal warrants against Nelson and 25 others on charges of high treason. Soon afterwards, Louis-Joseph Papineau* and Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan* joined Nelson at Saint-Denis where they decided to resist arrest, procure arms and ammunition for the people, and declare the independence of Lower Canada on 4 Dec. 1837.

The British authorities, however, decided to act long before that date. When they learned that the Patriotes were occupying Saint-Charles and that Papineau was with Nelson at Saint-Denis, they launched on the night of 22 November a two-pronged attack on the two Patriote strongholds. A brigade under Colonel George Augustus Wetherall set out from Chambly to move against Saint-Charles at the same time that another brigade under Colonel Charles Stephen Gore left Sorel on a secret march to take Saint-Denis, which, according to an officer on the march, “was not supposed to be strongly held.” The British tactics were not successful. Forewarned before dawn on the 23rd of the British approach by the capture of a British officer, Nelson went to reconnoitre the strength of their forces. Accounts differ as to exactly what followed, but it appears that Nelson returned to Saint-Denis determined to engage the British. He ordered the alarm bell rung, sent parties out to destroy bridges, and made preparations to resist from two stone houses at the north end of the town. He had informed Papineau of his reconnaissance trip, but he does not appear to have conferred with him regarding his intentions after his return. To the Patriotes with him he said: “A bit of courage, and victory will be ours.”

The opposing forces at Saint-Denis may have appeared grossly mismatched, a country doctor and his collection of farmers and tradesmen against a veteran of Waterloo and his selected companies of seasoned regulars. But Nelson had grown up among British soldiers and he was not intimidated by the sight of their military uniforms. Also, among Nelson’s angry, determined men were several first rate sharpshooters. On the other hand, although Gore was an earnest and hardworking deputy quartermaster-general he was not a brilliant tactician, and some of his men, who were part of an army which, in Wellington’s words, collected “the scum of the earth,” were waiting for a chance to slip away to the United States. Furthermore, the elements were in Nelson’s favour. He and his snipers remained dry behind thick stone walls while Gore and his soldiers, after having marched all night in freezing November rain, had to manoeuvre in mud. From about nine a.m. until mid afternoon, Gore attempted in vain to push his men past the Patriote position. He was forced instead to order a retreat.

The victory at Saint-Denis electrified Lower Canada and made Nelson a hero among the Patriotes. Even the British grudgingly admitted that he was “far more determined, courageous and active than any of his brother traitors.” But Patriote defeats followed the great victory and, worse still, Papineau disappeared, “leaving us,” Nelson later declared, “all in the lurch.” In just over a week, the defenders of Saint-Denis had diminished to six. In the face of Gore’s impending return, they fled to the woods on 1 December. For Nelson the aftermath was a nightmare. At Granby he became separated from his companions of Saint-Denis, and he wandered without food for ten days until he was captured by some volunteers near Stukeley in the Eastern Townships. He was then taken to Montreal to face trial on the charge of high treason. “Just before he started,” wrote a friend to Mrs Nelson, “he desired me to write a few lines saying that he willed all the property he possessed to his dear wife and children.” Nelson did not know at the time that Colonel Gore’s soldiers had burned most of his property on their return to Saint-Denis. But he did know that martial law had been declared and that the penalty for high treason was death.

Nelson, however, did not even come to trial. After spending seven months in prison, he and seven others were banished to Bermuda after pleading guilty in a private letter to Lord Durham [Lambton*] of “rebelling against colonial misgovernment.” In October 1838 another odd twist of fate, the disavowing of Durham’s ordinance, allowed the exiles to leave Bermuda. By early 1839 Nelson had found his way to Plattsburgh, N.Y., near the Lower Canadian border, where he established a medical practice and was joined by his family. When asked what should be done to liberate Lower Canada, he replied simply: “At this moment we must let time and circumstances do their work, however slowly.”

Time and circumstances did their work remarkably quickly. In 1842 Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, a friend who had offered to adopt one of Nelson’s children just before the exiles left for Bermuda, took office as attorney general for Canada East and entered a nolle prosequi in Nelson’s case. Nelson left Plattsburgh in August, to the regret of the people of that town, and moved his family to Montreal where once again he began a new medical practice.

Although he had vowed to stay out of Canadian politics when he returned, he kept his resolution for only two years. In 1844 La Fontaine requested him to stand for election to the assembly, and, fired by his indignation over Downing Street’s refusal to adhere to the principle of responsible government, he was unable to refuse. For the next seven years he was the member for Richelieu. To the disgust of Tories, he restaked his old political position as the English speaking exponent of French Canadian rights and was a firm advocate of responsible government.

During his parliamentary career there twice emerged the same angry man who had defied Dalhousie and defeated Gore. On the first occasion, in 1848, his opponent was Louis-Joseph Papineau. Back from exile and a member in the assembly, Papineau had begun manoeuvring to regain his leadership from La Fontaine by appealing to national prejudices. Nelson resented Papineau’s thinly veiled efforts to split the Reform alliance that had finally gained power. When Papineau insinuated that the violence of 1837 was attributable to Nelson, the latter turned on the great man himself and finally revealed that Papineau had been quite prepared to use force and had indeed signed a declaration of independence in his house. He also exposed Papineau’s hurried flight from Saint-Denis, only half an hour after the battle had started, and stated his belief that Papineau’s escape had resulted in the ultimate defeat of the Patriote movement and all the misery that had followed. “It is perhaps a favour for which we should thank GOD, that your projects failed,” he sneered, “persuaded as I am at present that you would have governed with a rod of iron.” Possibly only a man of Nelson’s reputation could have attacked so exalted a figure with such telling effect. Papineau’s power and popularity were mutilated. But Nelson’s own heroic stature was diminished by the vehemence of his attack; there is no doubt that in later years he regretted having made it.

A second outburst occurred during the fiery debate on the Rebellion Losses Bill [see James Bruce] which Nelson had helped frame. Taunted by Tories with accusations of being a rebel and a traitor, Nelson replied that to “Those who call me and my friends rebels I tell them that they lie in their throats. . . . I tell those gentlemen to their teeth, that it is they and such as they, who cause revolutions, who pull down thrones, trample crowns into the dust and annihilate dynasties.” He also offered to withdraw his own valid claim for losses, “wantonly inflicted as they were,” but demanded that those who had suffered innocently be paid. When royal assent was given to the bill in April 1849, Nelson had the satisfaction of knowing that the measure would benefit materially his constituents in the Richelieu valley, exonerate his own actions of 12 years earlier, and by its very passage, establish the principle of responsible government for which Nelson had fought since the beginning of his political career 22 years before. A little over a year later he announced his retirement from politics.

Nelson was 60, but he was not to retire yet. As a reward for his services to the La Fontaine-Robert Baldwin* ministry he was offered the position of inspector of provincial penitentiaries and jails, an office for which he was ironically well qualified. As he himself explained, “My sojourn for seven months in the Montreal Jail gave me such a practical knowledge of prison affairs, the accursed abuses that prevailed there . . . and the uncalled for miseries that were inflicted on the prisoners [as] induced me to accept.” With his characteristic energy he made a possible sinecure an important office. His reports on prisons, which have been described as “well written,” contain much valuable information.

Nor did he retire from politics. In 1854 he defeated Édouard-Raymond Fabre*, a Papineau supporter, to become the first popularly elected mayor of Montreal. No study has been made of Nelson’s career in municipal politics, but he appears by his speeches to have been a progressive administrator. In 1855 he urged the greater regulation of public services through the appointment of municipal inspectors. He favoured welfare for the poor when there was no work and he recommended that the municipal council seriously consider Sir James Edward Alexander’s idea of creating a park atop Mont-Royal. He retired from municipal politics in 1856.

Nelson seems never to have retired from his first profession. He was always a doctor – for the wounded British soldiers after Saint-Denis, among his fellow prisoners, among the blacks in Bermuda, and on the Montreal waterfront during the 1847 epidemic of ship-fever. He is credited with having performed with his son, Dr Horace Henry Nelson, the first operation using anaesthetics in Canada. As mayor of Montreal he published at his own expense a useful pamphlet in both English and French on the prevention of cholera. In the assembly he drew up legislation for the teaching of medicine and the regulation of the profession. It comes as no surprise to find him putting medicine ahead of politics. In 1851 he wrote to his friend William Lyon Mackenzie regretting having missed the opening of the session because of three or four serious cases. “I have endeavoured to put [them] into quite as good hands but my patients will not hear of it.” Although Nelson’s historical reputation rests upon his political activities, possibly his greater contribution lies in his long and honourable medical career. His services to thousands of people during his 50 years as a doctor, however, can never be known.

Wolfred Nelson revealed throughout his life a strong humanitarian concern, and actions in small events which reveal this quality are part of the accurate measure of the man. While being transported to Bermuda he feared that certain comments he had made regarding opportunities for escape that he had refused might implicate his jailer; he wrote the jailer to set the record straight and to commend him on his “humanity and due regard to the feelings of the prisoners.” In 1854 he took the trouble to write a letter that helped the unpopular Tory colonel, Bartholomew Conrad Augustus Gugy*, disprove allegations of cruelty in 1837. Nelson gratefully recalled the kindness shown by his old opponent Gugy to Mrs Nelson following Gore’s return to Saint-Denis. In the union Legislative Assembly he made his first speech in 1845 in French, a language proscribed at the time, and in 1849 he seconded an amendment to the Rebellion Losses Bill that prohibited him from making any claim for his own losses. On a cold January night in 1849 he acted as chairman of a meeting called to promote the abolition of capital punishment, which he termed “judicial murder.” Wolfred Nelson died in Montreal on 17 June 1863 at the age of 71. The small white marker over his grave reads: “Here lieth God’s noblest work, an honest man.”

Wolfred Nelson, Practical views on cholera, and on the sanitary, preventive and curative measures to be adopted in the event of a visitation of the epidemic (Montreal, 1854; a French edition was published in Montreal in the same year).

PAC, MG 24, A27, ser.2, 26, pp.631–37, 652–53; A40, 9, pp.2273, 2344, 2432–34, 2457, 2475–77, 2574, 2589; 27, pp.8156, 8170; B14; B31, 1, p.40; B34; B37, 1, p.118; B82; RG 4, A1, S-112; S-203a; S-272, pp.73–74; S-507, pp.73–75; S-586, pp.42–42a; RG 8, I (C series), 281, p.222; 1717, p.59; RG 9, I, A7, 21. PRO, CO 42/274, 10–11 (mfm. at PAC). “Les Patriotes aux Bermudes en 1838, lettres d’exil,” Yvon Thériault, édit., RHAF, XVI (1962–63), 267–72. La Minerve, mai-oct. 1848, juin 1863. Pilot and Journal of Commerce (Montreal), Nov.-Dec. 1844, Jan. 1849. Vindicator and Canadian Advertiser (Montreal), April-Dec. 1837. Borthwick, History and biographical gazetteer. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. Abbott, History of medicine. Christie, History of L.C., IV, V. Azarie Couillard-Després, Histoire de Sorel de ses origines à nos jours (Montréal, 1926). Monet, Last cannon shot. Wolfred Nelson, Wolfred Nelson et son temps (Montréal, 1946). B. B. Kruse, “The Bermuda exiles,” Canadian Geographical Journal (Ottawa), XIV (1937), 353.

Cite This Article

John Beswarick Thompson, “NELSON, WOLFRED,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelson_wolfred_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nelson_wolfred_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | John Beswarick Thompson |

| Title of Article: | NELSON, WOLFRED |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |