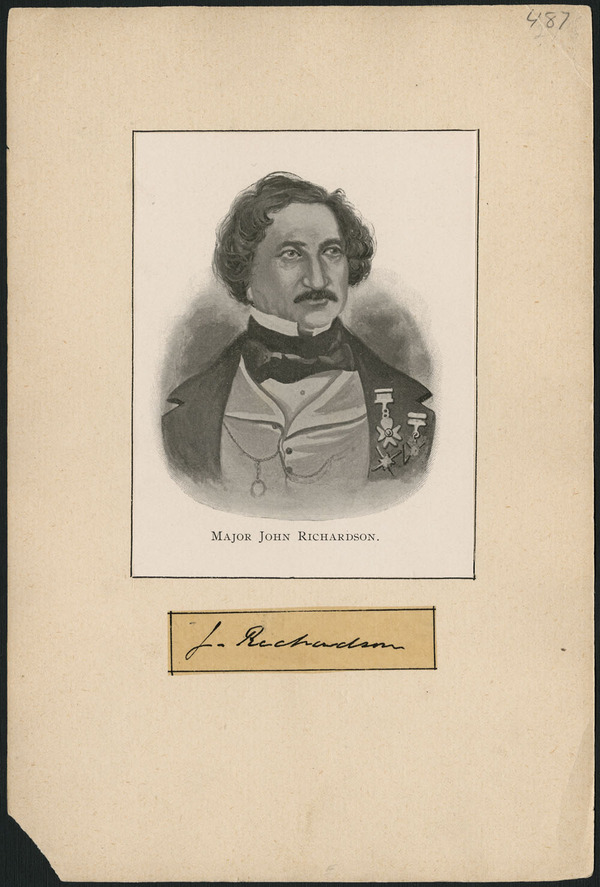

RICHARDSON, JOHN (he also on occasion used the middle name Frederick), army officer, author, newspaperman, and office holder; b. 4 Oct. 1796 probably at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada, son of Robert Richardson and Madelaine Askin; m. first 12 Aug. 1825 Jane Marsh; m. secondly 2 April 1832 Maria Caroline Drayson; he had no children; d. 12 May 1852 in New York City.

John Richardson was a grandson on his mother’s side of the fur trader and merchant John Askin* and Manette (Monette), a native woman believed to have been an Ottawa. His father came to Upper Canada from the Annandale district of Scotland as a surgeon with the Queen’s Rangers. He met and married Madelaine Askin in Queenston in 1793 and eventually settled in Amherstburg on the Detroit River. There John spent his adolescent years.

In July 1812, one month after war had broken out between the United States and Great Britain, Richardson, at the age of 15, joined the 41st Foot as a volunteer. He took part in several military engagements near Lake Erie. Fighting with Indian forces led by his hero Tecumseh*, Richardson had an opportunity to observe the character of Indian warriors. He relied upon this experience when he came to write the novels Wacousta, Hardscrabble, and Wau-nan-gee. On 5 Oct. 1813 he was captured at the battle of Moraviantown and imprisoned in Kentucky. He was later to describe his war service in an essay, “A Canadian campaign, by a British officer.”

Released in July 1814, he joined the 8th Foot (in which he had been commissioned ensign on 4 Aug. 1813) in October and was sent to Europe with it in June 1815 to fight Napoleon’s last army. Arriving too late to engage in the battle of Waterloo, he was promoted lieutenant in July and then went on half pay in London in February 1816 before joining the 2nd Foot as a second lieutenant in May. He served with this regiment for more than two years, primarily in Barbados and Grenada. As a result of a severe case of malaria and for personal reasons, he went on half pay again in the autumn of 1818 in the 92nd Foot. For at least three years Richardson lived in London and then moved to Paris, where in 1825 he married for the first time. His experiences in these cities were later to figure in the novels Écarté and Frascati’s. By 1826 he was back in London, where he published the poem Tecumseh; or, the warrior of the west (1828). His personal narrative, “A Canadian campaign,” was serialized in 1826–27 in the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London), and another, “Recollections of the West Indies,” probably first appeared at this time (it was later serialized in the New Era in 1842). He also engaged in journalism, began writing novels, and pestered the War Office to be taken back on active duty.

Richardson’s first novel, Écarté; or, the salons of Paris, was published by Henry Colburn in London in 1829. Although it became a reference for preachers who wished to warn their congregations against the evils of gambling, the novel was more sensitive and profound than a mere object lesson for preachers and was, as one reviewer remarked, full of “fine moral antithesis.” In his novels Richardson aimed for a realistic depiction of life, a perspective he later commended in the writings of Charles Dickens, whom he considered “nature’s purest and most faithful painter.” Écarté’s sequel, Frascati’s; or, scenes in Paris (1830), written with Justin Brenan, describes how Irish tourists were taken in by tricksters in Paris. It was his third work, the historical novel Wacousta; or, the prophecy (1832), which became popular and established Richardson’s fame.

In Wacousta, Sir Reginald Morton, an English nobleman, comes to British North America to seek revenge for the loss of his fiancée to a fellow officer and friend, Charles de Haldimar. Disguised as an Indian and adopting the name Wacousta, he helps Pontiac* lead an armed uprising in 1763 against English forts in the northwest. Only Detroit is saved because an Indian woman in love with the elder son of the fort’s commander, de Haldimar, gets word to him of the Indians’ planned ruse: to play field hockey outside the fort, pretend to chase the ball into the fort, and then slay the inhabitants. Before the end of the novel Wacousta kills two of de Haldimar’s children and a curse is uttered by Wacousta’s niece which prophesies the end of the de Haldimar line.

In writing the novel, Richardson made use of accounts of the siege of Detroit in 1763 and of the attack on Fort Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City, Mich.) which he had heard as a boy [see Minweweh*]. Wacousta himself was loosely modelled after John Norton*, son of a Cherokee father and a Scottish mother, who was raised in Scotland and came to British North America in 1785 with the 65th Foot. Norton was later appointed a Mohawk chief (Teyoninhokarawen), and worked closely with Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] negotiating the controversial settlement of the Six Nations Indians near the Grand River. As a small boy Richardson had himself encountered Norton, who had been a trading agent for John Askin, and in 1816 he appealed to Norton for assistance when he was seeking to return to full pay in London. The name Sir Reginald Morton, however, Richardson derived from Sir Reginald Norton, who died at Faversham, England, in 1500. The Norton family was closely connected for centuries with the Drayson family; Sir Reginald himself married a Drayson, and members from both families filled the office of mayor of Faversham in the 16th century. At the time he was writing Wacousta, Richardson was courting Maria Caroline Drayson, whom he married in the year it was published, and he doubtless heard of the Norton connection from her father, William, who was interested in genealogy. There are also obvious literary progenitors for the mighty Wacousta, the outlaw wreaking revenge on society for an injustice done to him; Milton’s Satan and Schiller’s Karl Moor are among them, as are the heroes of Byron who seek redress for the betrayal of friendship. When the American edition of 1851 appeared, critic Evert Augustus Duyckinck wrote: “This is one of these curiously compounded works, criticism stops at, because, in the first place it is sure of the sympathies of a large circle of readers; shows talent throughout; and yet, at the same time, is scarcely amenable to the strict standards of judgement.”

Richardson’s use of historical events did not serve so well the sequel to Wacousta, entitled The Canadian brothers; or, the prophecy fulfilled (1840). He called this novel “a Canadian national novel” since he drew again upon his personal experiences to describe the border warfare in the War of 1812 from a Canadian viewpoint. The Canadian brothers lacked the intensity of Wacousta and was not as popular. It was published in Montreal in 1840, the only one of his novels to appear first in Canada. In 1851 it was issued in the United States in an altered version under the title Matilda Montgomerie: or, the prophecy fulfilled, but it was never published in England, owing no doubt to its Canadian character.

In 1835 Richardson’s wish to return to active service had been realized after a fashion when, as a captain, he joined the British auxiliary legion raised for service in Spain during the First Carlist War. His Journal of the movements of the British Legion, published in 1836, and the next edition of the work, Movements of the British Legion (1837), were used by Tories to embarrass the Whig government of Lord Melbourne, whose representatives retaliated by making personal attacks on Richardson in parliament. But the troubles of the British Legion were internal as well, and Richardson, by describing his sufferings at the hands of its commander, Lieutenant-General George de Lacy Evans, exposed the petty intrigues of military adventurers and place-seekers. His Personal memoirs (1838) and a satirical novel, “Jack Brag in Spain” (serialized in the New Era in 1841–42), continued his exposé of the British Legion. While still serving in Spain he had been brought before a military court of inquiry for casting “discredit on the conduct of the Legion,” a charge altered to “cowardice in battle.” Richardson, who had been wounded in the campaign, was exonerated, and then promoted major in 1836. Henceforth, his books, which had been published anonymously, carried his name and rank.

Another product of the Spanish campaign was a knighthood in the military Order of St Ferdinand, which he had received for courage in battle. It was his most prized award aside from his majority. From boyhood Richardson had developed a passionate interest in chivalry, and while in Europe he became an adherent of Saint-Simon’s belief that the individual is responsible for maintaining his personal dignity, a gift derived directly from the Creator. He was later to transform the role of knight into fiction in The monk knight of St. John; a tale of the Crusades (1850), in which a Crusader named Abdallah, the monk knight, is put to the test in that era of murder and rapine.

In the spring of 1838 the Times of London, a Tory newspaper, hired Richardson on a year’s contract as foreign correspondent to cover the rebellions of 1837–38 in Upper and Lower Canada, perhaps as compensation for his services to the Tories. After his arrival in Montreal, however, Richardson became a strong supporter of the governor-in-chief, Lord Durham [Lambton*], prompting the Times to dismiss him. Richardson was also left with political enemies in the Canadas when Durham was recalled.

Richardson, in Eight years in Canada (1847) and its sequel, The guards in Canada; or, the point of honor (1848), provides a valuable contemporary account of events under the administrations of Durham, Lord Sydenham [Thomson*], Sir Charles Bagot*, and Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, and describes his personal vicissitudes in the period from 1838 to 1848. In these years he threw himself into journalism and the political fray on behalf of the conservative opposition. Having sold his lieutenancy to buy a printing-press in June 1840, he settled in Brockville in July and published there from June 1841 to August 1842 the New Era, or Canadian Chronicle, in which he tried to bring “polite literature” to Canadians. Then, living in Kingston, he issued the Canadian Loyalist, & Spirit of 1812 from January 1843 to July 1844. Once again Richardson made himself a controversial figure. He feuded with members of the British military and with French Canadian conservatives led by Clément-Charles Sabrevois* de Bleury who were opposed to Durham’s plan for the union of the Canadas. In 1842 Richardson edited his earlier work, “A Canadian campaign,” fleshed it out with excerpts from official war documents, and serialized it in the New Era as “Operations of the right division.” The articles were well received and were republished in book form as War of 1812. Richardson hoped that the book would be used in schools, and applied to the Legislative Assembly for a grant to publish two more volumes. He received £250 but claimed that the grant did no more than cover his expenses in publishing the first volume. In fact, he placed the remaining copies of War of 1812 on auction to pay creditors; only one was sold, and no further volumes were issued. Francis Hincks*, who had opposed the grant for fear that Richardson would use it to help his newspapers, became a relentless political enemy and attacked Richardson regularly in print. In 1843 Richardson stirred up yet more controversy when, on 17 October, he fought a duel with Stewart Derbishire* over the latter’s ardent defence of those responsible for the death of a 16-year-old youth in an Orange Day confrontation.

Despite his frequent quarrels with senior political officials, Richardson repeatedly tried to win appointment to government office, but his enemies were too numerous. Early in 1842 he had petitioned Queen Victoria in vain for a pension, claiming to be “the only Author this Country has hitherto produced.” After his newspapers failed he fell into debt. Finally in May 1845 Governor Metcalfe, whom Richardson had energetically supported in the Canadian Loyalist, appointed him superintendent of police on the Welland Canal, and Richardson and his wife moved to St Catharines.

With only a small band of men to help him, Richardson now faced the unenviable task of maintaining order on the Welland Canal, where rioting, often politically instigated to embarrass the government, had broken out among Irish canal workers, who also protested the starvation wages paid by private contractors. Despite the antagonism of his employer, the Board of Works, whose members were reformers opposed to Metcalfe, Richardson set out to fashion a disciplined force and end violence along the canal. He went through a series of humiliations, violent confrontations, and a farcical trial in his struggle to assert his authority before all real power was taken away from him. His troubles were compounded by the unexpected death on 16 Aug. 1845 of his wife from apoplexy provoked by the strain of her husband’s difficulties. In December, when it appeared that relative peace had been restored, Samuel Power, the chief engineer and an employee in favour with the Board of Works, recommended that the police force be reduced and Richardson be dismissed since his presence was no longer required. Richardson was dismissed from office at the end of January 1846. His account of the Welland Canal episode was published that year as Correspondence (submitted to parliament).

From August 1846 to January 1847 Richardson tried his hand at political muck-raking by publishing a weekly newspaper in Montreal, the Weekly Expositor; or, Reformer of Public Abuses and Railway and Mining Intelligencer. During this time he also did some writing for the Montreal Courier. The passage in April 1849 of the Rebellion Losses Bill, which granted the rebels of 1837–38 compensation equal to that received by the loyalists for losses suffered during the uprising, offended loyalists and led to rioting in Montreal. The troubles prompted Richardson to relocate in New York in the fall of 1849. Americans, after all, celebrated him as an author while Canadians showed little interest in his work.

Richardson’s entry on the American literary scene was heralded by the serialization in Sartain’s Union Magazine of Literature and Art (Philadelphia) from February to June 1850 of his new novel, Hardscrabble; or, the fall of Chicago, which centres around the Indian siege of Fort Dearborn (Chicago) in 1812. His writings resulted in an increased readership of Sartain’s, just as the serialization of his next novel, Wau-nan-gee; or, the massacre at Chicago, did for the New York Sunday Mercury in 1851. Despite his apparent success, Richardson’s financial situation does not seem to have improved. Although his novels Écarté, Wacousta, and The Canadian brothers (retitled Matilda Montgomerie) were republished with as much critical and popular success as his newer works, including The monk knight, he made little money from them because he was forced by his straitened circumstances to sell them to the publishers for reduced lump sums.

In New York he also wrote short stories for American periodicals and at least two songs. One of the latter, “All hail to the land,” set to music by harpist Charles Nicholas Bochsa and published in October 1850, was a national song. A short story, “Westbrook; or, the renegade,” was initially rejected in 1851 in a contest held by Sartain’s, but Richardson subsequently extended it into a short novel, Westbrook, the outlaw, at the suggestion of the editor of the Sunday Mercury, where it was serialized in the fall of 1851. It was based on a real person, Andrew Westbrook*, a farmer living in Upper Canada in the vicinity of the village of Delaware on the Thames River. During the War of 1812 Westbrook led American marauding parties into the province and was branded an outlaw by the Upper Canadian courts in 1816. Richardson depicted him as a villain whose revenge for the loss of a district militia command to a young neighbour of the local gentry was to imprison the youth’s sister in an isolated cabin and rape her every day until he was discovered. Richardson’s inspiration may have come in part from the rebellion of New York farmers around Albany against landowners in the 1840s, and the portrayal of the farmers in New York City newspapers as bloodthirsty savages. Although published in book form in 1853, the novel to all intents and purposes was lost until 1973 when the newspaper serialization turned up at a book auction in New York.

Richardson’s last publication, Lola Montes: or, a reply to the “Private history and memoirs” of that celebrated lady (1851), was written in defence of the dancer and actress who arrived in New York late that year. He published it anonymously at his own expense, but it was a commercial failure. His fortunes, which were at a “very low ebb,” were hurt rather than revived. Richardson died in New York on 12 May 1852 of erysipelas brought on by undernourishment. His friends took up a collection to pay the expenses of his funeral but there is no record of where he is buried, other than that his body was removed from the city.

Throughout his life Richardson defended his individuality to a point where many considered him quarrelsome, unreasonable, and enigmatic. Sensitive to slights, he was ever ready to fight a duel, and took part in many. Although an excellent shot with pistols, he claimed that he did not provoke confrontations but rather became involved only when it was necessary to uphold his dignity. His sharp criticism of his contemporaries and their utilitarianism sprang from his belief in the overriding need to develop the individual personality. During the 1840s he became sympathetic to the fatalistic teachings of the American sect leader William Miller, with his prophecies of the end of the world. Later, when he lived in New York, Richardson followed the evangelical preacher William Augustus Muhlenberg, who proclaimed the universality of Christianity and emphasized the spiritual power of love.

Richardson’s strengths included a dedication to Canada’s national progress, particularly evident in his support of Lord Durham and responsible government, and his antagonism to what he regarded as corrupt and irresponsible bureaucracies. An over-zealous pursuit of his goals and ideals along with too great an expectation of reward and success brought him enemies unnecessarily. He was, moreover, of an impatient and egotistical temperament. Although a champion of integrity and considerate behaviour, which he saw as exemplified in the chivalric code, he was not above small lies and looking out for his own interests. Thus he too was human, like the fictional characters through whom he tried to bring reality into literature. Certainly he was quick to anger and he pursued his objectives with stubborn perseverance, but he was not without the foresight of a visionary, a subtle sense of humour, and literary talents that were recognized by some of his contemporaries.

Richardson described his “inventive genius” as a natural talent: “The power so to weave together the incidents of a tale that they may be made comprehensible and attractive to the reader, is a mere gift, which some persons possess in a greater or less degree than others; and can reflect no more credit upon him who is endowed with it, than can reasonably be claimed by any man or woman who has been, by nature, fortunately gifted with personal beauty and attraction superior to that enjoyed by the generality of their kind.” He showed no patience for Canadians who, by neglecting their writers, demeaned themselves in the eyes of the civilized world. “True, I have elsewhere remarked that the Canadians are not a reading people. Neither are they: but yet there are many hundreds of educated men in the country, who ought to know better, . . . who possess a certain degree of public influence, and who should have been sensible that, in doing honor to those whom the polished circles of society, and even those of a more humble kind, have placed high in the conventional scale, they were adopting the best means of elevating themselves.”

Unrecognized by Canadians, he was almost forgotten, and in one of his frequent moments of frustration in Canada wrote that “should a more refined and cultivated taste ever be introduced into the matter-of-fact country in which I have derived my being, its people will decline to do me the honor of placing my name in the list of their Authors.” It was a long time before his life aroused interest and his novels began to receive attention as energetic and complex creations. A promoter of a Canadian national literature in his day, Richardson would have been pleased to find that his works are now recognized as a contribution to its development.

Many of John Richardson’s full-length works were published first in serial form; some, especially the novels and in particular Wacousta, were republished frequently and in different versions. The following lists his most important extant writings, and references to books give only the first date of known separate publication. Fuller bibliographies, which include references to works that have not survived in their entirety or at all, and more complete information on Richardson’s literary production are given in the author’s The Canadian Don Quixote: the life and works of Major John Richardson, Canada’s first novelist (Erin, Ont., 1977), 198–202, which is also the first full-length biography of John Richardson, and in A bibliographical study of Major John Richardson, comp. W. F. E. Morley (Toronto, 1973), which includes a biographical introduction by Derek F. Crawley. The reader should also refer to The Canadian Don Quixote for additional sources on Richardson’s career.

Richardson wrote the following novels: The Canadian brothers; or, the prophecy fulfilled: a tale of the late American war (2v., Montreal, 1840), republished as Matilda Montgomerie: or, the prophecy fulfilled; a tale of the late American war, being the sequel to “Wacousta” (New York, 1851); Écarté; or, the salons of Paris (3v., London, 1829); Frascati’s; or, scenes in Paris (3v., London, 1830), written with Justin Brenan; Hardscrabble; or, the fall of Chicago: a tale of Indian warfare (New York, [1850 or 1851]); The monk knight of St. John; a tale of the Crusades (New York, 1850); Wacousta; or, the prophecy: the tale of the Canadas (3v., London and Edinburgh, 1832); Wau-nan-gee; or, the massacre at Chicago: a romance of the American revolution (New York, [1852]); and Westbrook, the outlaw; or, the avenging wolf (New York, 1853), which has been reprinted with a preface by D. R. Beasley (Montreal, 1973). His poetry includes Kensington Gardens in 1830: a satirical trifle (London, 1830); “Miller’s prophecy fulfilled,” Canadian Loyalist, & Spirit of 1812 (Kingston, [Ont.]), 1 Feb. 1844 (a single copy is extant, at the PAC), which has been edited and republished by D. R. Beasley and W. F. E. Morley in the Papers of the Biblio. Soc. of Canada (Toronto), 10 (1971): 18–28; and Tecumseh; or, the warrior of the west: a poem, in four cantos, with notes (London, 1828).

Among Richardson’s important works of non-fiction are “A Canadian campaign, by a British officer,” New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London), new ser., 17 (July–December 1826), pt.ii: 541–48; 19 (January–June 1827), pt.i: 162–70, 248–54, 448–57, 538–51; Correspondence (submitted to parliament) between Major Richardson, later superintendent of police on the Welland Canal, and the Honorable Dominick Daly, provincial secretary . . . (Montreal, 1846); Eight years in Canada; embracing a review of the administrations of Lords Durham and Sydenham, Sir Chas. Bagot, and Lord Metcalfe, and including numerous interesting letters from Lord Durham, Mr. Chas. Buller and other well-known public characters (Montreal, 1847); The guards in Canada; or, the point of honor: being a sequel to . . . “Eight years in Canada” (Montreal, 1848); Journal of the movements of the British Legion (London, 1836), published in a 2nd edition as Movements of the British Legion, with strictures on the course of conduct pursued by Lieutenant-General Evans (London, 1837); Lola Montes: or, a reply to the “Private history and memoirs” of that celebrated lady, recently published, by the Marquis Papon . . . (New York, 1851); “Operations of the right division of the army of Upper Canada, during the American War of 1812,” New Era, or Canadian Chronicle (Brockville, [Ont.]), 2 March–22 July 1842, republished as War of 1812, first series; containing a full and detailed narrative of the operations of the right division, of the Canadian army ([Brockville], 1842); Personal memoirs of Major Richardson . . . as connected with the singular oppression of that officer while in Spain by Lieutenant General Sir De Lacy Evans (Montreal, 1838); and “Recollections of the West Indies,” New Era, or Canadian Chronicle, 2 March–24 June 1842.

Reprints of Richardson’s works which also contain useful biographical information include The Canadian brothers . . . , intro. C. F. Klinck (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974); Richardson’s War of 1812, with notes and a life of the author, ed. A. C. Casselman (Toronto, 1902); and Tecumseh and Richardson: the story of a trip to Walpole Island and Port Sarnia, ed. A. H. U. Colquhoun (Toronto, 1924). See also Major Richardson’s short stories, ed. D. R. Beasley (Penticton, B.C., 1985). In addition, the Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts (Ottawa) has among its projects the republication of Wacousta.

New York Public Library, mss and Arch. Division, Duyckinck family papers, E. A. Duyckinck diary, 13 Sept. 1851. PAC, RG 5, C1, 196, Richardson to Lord Elgin, 10 May 1847. PRO, WO 25/772: 130v. G.B., Parl., Hansard’s parliamentary debates (London), 3rd ser., 38 (1837): 2–123. Literary World (New York), 1 March 1851. Mirror of Parliament (London), April 1837. New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London), new ser., 27 (January–December 1829), pt.iii: 189–90. Pick (New York), 22 May 1852. Sunday Mercury (New York), 16 May 1852. DNB. Major John Richardson; a selection of reviews and criticism, ed. Carl Ballstadt (Montreal, 1972). D. R. Cronk, “The editorial destruction of Canadian literature: a textual study of Major John Richardson’s Wacousta; or the prophecy” (ma thesis, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby, B.C., 1977). Dennis Duffy, Gardens, covenants, exiles: loyalism in the literature of Upper Canada/Ontario (Toronto, 1982). Michael Hurley, “The borderline of nightmare: a study of the fiction of John Richardson” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1984). Robert Lecker, “Patterns of deception in Wacousta,” The Canadian novel, ed. John Moss (3v. to date, Toronto, 1978– ), 2: 47–59. C. W. New, Lord Durham; a biography of John George Lambton, first Earl of Durham (Oxford, 1929). James Reaney, Wacousta! (Toronto, 1979). W. R. Riddell, John Richardson (Toronto, 1923). T. D. MacLulich, “The colonial major: Richardson and Wacousta,” Essays on Canadian Writing (Downsview [Toronto]), no.29 (summer 1984): 66–84. Desmond Pacey, “A colonial romantic: Major John Richardson, soldier and novelist,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), no.2 (autumn 1959): 20–31; no.3 (winter 1960): 47–56.

Cite This Article

David R. Beasley, “RICHARDSON, JOHN (John Frederick),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_john_1796_1852_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_john_1796_1852_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | David R. Beasley |

| Title of Article: | RICHARDSON, JOHN (John Frederick) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 22, 2025 |