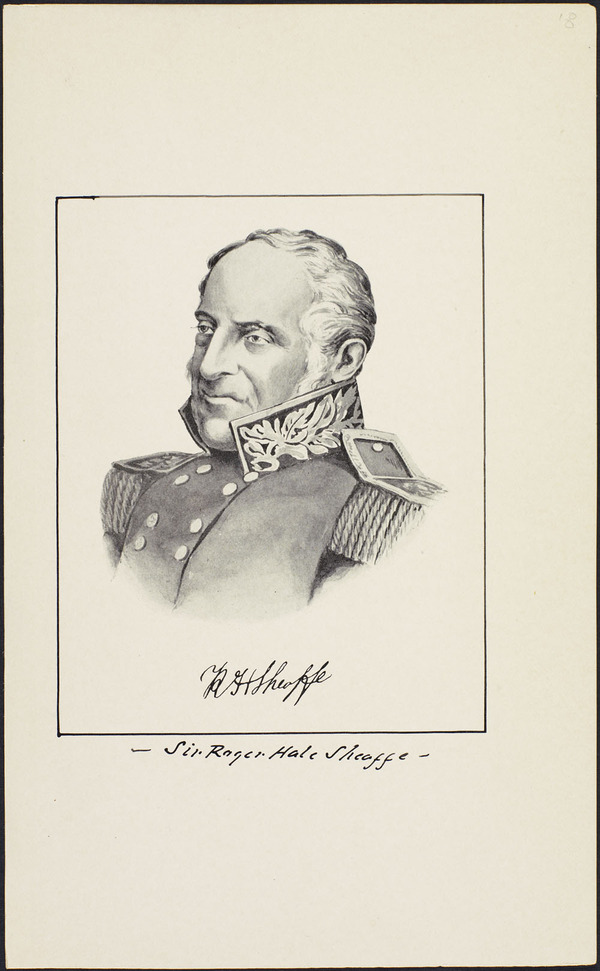

SHEAFFE, Sir ROGER HALE, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 15 July 1763 in Boston, third son of William Sheaffe, deputy collector of customs, and Susannah Child; m. 29 Jan. 1810 Margaret Coffin, daughter of John Coffin*, at Quebec, and they had two sons and four daughters, all of whom predeceased Sheaffe; d. 17 July 1851 in Edinburgh.

As a young boy Roger Hale Sheaffe became the protégé of the Duke of Northumberland, who during the American Revolutionary War had established his headquarters in Boston in the boarding-house run by the widowed Susannah Sheaffe. The duke initially sent the lad to sea, but then transferred him to Locke’s military academy in Chelsea (London), England, where he was a class-mate of George Prevost*. Northumberland subsequently bought most of Sheaffe’s commissions, beginning in May 1778 with that of ensign in the 5th Foot, of which the duke was colonel. After serving in Ireland for six years, Sheaffe arrived at Quebec in July 1787 with his regiment, which was transferred to Montreal the following year. The 5th was subsequently stationed at Detroit, from 1790 to 1792, and then at Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) until 1796, when it returned to Quebec. In August 1794, prior to the signing of Jay’s Treaty, Sheaffe had acted as Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe*’s emissary to Sodus, an Indian community on the south shore of Lake Ontario, where he protested seizures of Indian lands by a settlement agent, Charles Williamson. Described by Simcoe as a “Gentleman of great discretion, incapable of any intemperate or uncivil conduct,” Sheaffe was promoted captain in May 1795.

As a result of his regiment’s being drafted, he returned to England in September 1797 and three months later purchased a majority in the 81st Foot. The following March he became junior lieutenant-colonel of the 49th Foot. At this point his career became linked with that of Isaac Brock*, the senior lieutenant-colonel. They served in north Holland together in 1799. The next year, when Brock left Sheaffe in command of the regiment, then stationed on Jersey, Sheaffe became unpopular with the men. After serving in the Baltic campaign of 1801, the two officers were ordered to the Canadas in 1802, arriving with the 49th in Lower Canada late that summer and taking up commands in the spring of 1803 in the upper province: Brock at regimental headquarters in York (Toronto) and Sheaffe, with a wing of the regiment, at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake).

It was there that Sheaffe’s abilities as a military commander were first subjected to serious question. In August 1803 he and other officers warned Brock of an incipient mutiny at Fort George, which Brock quickly suppressed. Brock believed that the fort’s proximity to the American border had been the major cause for the attempted desertion. But, conscious of Sheaffe’s past conduct when in command, he also censured him for being “indiscreet and injudicious,” particularly by behaving like a martinet, working his men too hard, and disciplining them too harshly for small lapses. Brock identified his reduction of “too many non-commissioned officers” as another contributing factor. Writing about the incident to Lieutenant-Colonel James Green* in 1804, he mentioned that Sheaffe possessed “little knowledge of Mankind” and had many enemies, although he could not offer any reasons for this enmity other than the bitter feelings which existed between Sheaffe and the men he commanded. William Dummer Powell*, and possibly other friends of Sheaffe, claimed after the War of 1812 that some of the submerged hostility in 1803–4 was based on Sheaffe’s American origin which raised doubts about his loyalty; Powell at least believed it to be faultless. Sheaffe’s actions in wartime would provide both his critics and his friends with support for their opinions. In 1808 he attained the brevet rank of colonel; three years later, as a result of his promotion to major-general, he was obliged to give up his command in the 49th and with it at least half his income.

In July 1812, some time after Sheaffe had returned from a trip to England, without specific duties, Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost, who had become governor-in-chief and commander of the forces, was anxiously looking for general officers to fill various wartime commands. Aware of Sheaffe’s financial plight, he also believed him to be well qualified to serve in Upper Canada because he would be a “Valuable Officer to the service from his Ability to command and his extensive local information.” In addition to his long service in the colony, he had useful connections within its social and political élites, principally through Powell, a pillar of the “family compact” and a long-time friend of the Sheaffe family. Without knowing if Sheaffe had been posted elsewhere by the military authorities in England, Prevost appointed him temporarily to the army staff in the upper province, thus putting him under Brock’s command once again.

Sheaffe arrived at Fort George on 18 August to find himself, as a result of Brock’s departure to repulse the American invasion on the Detroit frontier, in command of the forces on the Niagara frontier. Within days he learned of Prevost’s truce with Major-General Henry Dearborn. Having received news of Brock’s capture of Detroit before it reached Major-General Stephen Van Rensselaer, the opposing American commander on the Niagara River, Sheaffe slyly arranged with him a codicil to the armistice whereby no reinforcements or supplies could be forwarded to the upper Great Lakes, which meant that neither side could reinforce Detroit. Prevost, however, was incensed, for the truce had placed no restriction on troop and supply movements by either side. At the same time, he admitted to Brock, disavowal of Sheaffe’s initiative would embarrass the British, so no action was taken.

Late in August Sheaffe relinquished command to Brock, who had returned to the Niagara peninsula. The general armistice was ended on 4 September and both Brock and Sheaffe worked determinedly to strengthen the frontier’s defences. Early on 13 October the Americans attacked at Queenston. Brock hurried quickly from Fort George to take command on the battlefield, leaving Sheaffe to assemble and bring up the main body of defenders. When Brock was killed in a daring direct assault, Sheaffe took command, leading his force from the fort in a wide flanking movement to join with the Indians and a party from Chippawa under Captain Richard Bullock to attack the American flank on high ground. The invaders were routed and almost 1,000 prisoners were taken, with insignificant British losses. John Beverley Robinson*, a militia officer at the time, recalled Sheaffe’s conduct in battle as “cool though determined and vigorous.” His manœuvre had been brilliant and on 16 Jan. 1813 he would receive the deserved honour of a baronetcy for his achievement, though in the public’s memory Brock was the victor.

Following the battle, a three-day armistice had been immediately arranged by Sheaffe to allow each side to attend to its wounded and dead and to exchange prisoners. After he agreed to the American request for an indefinite extension, however, Prevost criticized him for not seizing the chance to cross the river instead to take Fort Niagara and for not getting prior approval of the extension. Many commentators in both Upper and Lower Canada, including the Quebec Gazette, thought that his leniency betrayed weakness and benefited only the Americans by giving them time to reorganize.

On Brock’s death, Sheaffe had succeeded him as military commander of Upper Canada, and also as president and civil administrator of the province’s government. He transferred his headquarters to York and on 20 October took the oath of office. During his term the effects of the war became fully evident. The problems of the dependability and loyalty of civilians plagued Sheaffe as they had Brock. On 9 November Sheaffe appointed alien boards at Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), York, and Kingston to examine all persons claiming to be American citizens and therefore exempt from military service [see Michael Smith*]. As military commander, Sheaffe had to deal with a weak militia force and with the inefficiencies of several army departments, particularly the barrack department and the commissariat. Despite his serious, sustained efforts to remedy organizational weaknesses and the attendant shortages of military supplies, such fellow officers as Thomas Evans* and Christopher Myers knew that Sheaffe would be blamed for problems inherited from Brock, who had been more interested in action than in bureaucratic efficiency. By January the first signs of food shortages had begun to appear, in the Western District, where Colonel Henry Procter* was empowered by Prevost through Sheaffe to impose a partial operation of martial law to force farmers to sell produce to the army.

During the winter of 1812–13, most of which Sheaffe spent on the Niagara frontier (probably at Fort George), he seldom dealt with civil matters because of poor health and preoccupation with military defence. The armistice negotiated after the battle of Queenston Heights ended on 20 November. After an unsuccessful American invasion near Fort Erie on the 28th, the commanding officer of the British forces there, Lieutenant-Colonel Cecil Bisshopp*, feared a second attempt and requested reinforcements. Sheaffe wisely responded that troops could not be sent to that distant position, where they could easily be isolated and defeated, and advised him to retreat to Chippawa if the Americans attacked. An indignant Bisshopp presented Sheaffe’s proposal to a council of officers, who were outraged that their commander should countenance retreat. Although the suggestion was theoretically a valid military plan, Sheaffe was seen to be injudicious in recommending it before it became a necessity, and rumour quickly labelled him a traitor. He lost standing with many regular and militia officers, notably Captain Andrew Gray, the deputy quartermaster general, and with a significant portion of the civilian population, a shift in opinion that alarmed Prevost.

Throughout the winter months of 1812–13 Sheaffe continued his efforts to remedy defensive weaknesses in the province. One of his major concerns was the need to ensure naval supremacy on the lakes when the shipping season opened [see George Benson Hall*]. He was well aware that Commodore Isaac Chauncey of the United States Navy had virtually seized control of Lake Ontario just before the winter freeze-up. By mid December Sheaffe and others had devised a plan “for the improvement of our marine establishment” by fitting out and arming additional vessels at Kingston, York, and Amherstburg. During part of January and February, however, Sheaffe’s illness so interfered with his work that Prevost ordered the next available senior officer in Upper Canada, Colonel John Vincent*, to proceed to Fort George and to be ready to take over the command of the province. In spite of his sickness, Sheaffe was able to endorse the formation of new corps as another obvious means for bolstering the province’s defences. He welcomed the suggestion initiated by Procter and promoted by Colonel William Caldwell* to form a corps of rangers similar to Butler’s Rangers in the American Revolutionary War. In February, Sheaffe supported Caldwell’s proposals before Prevost. The Western Rangers, also known as Caldwell’s Rangers, was formed in March and part of the credit may belong to Sheaffe.

He opened the Upper Canadian legislature on 25 Feb. 1813 and prorogued it on 13 March. This was the only session that he presided over but it acceded to most of his requests. The principal measures passed were the recognition of army bills authorized by the Lower Canadian legislature as legal tender in Upper Canada, the authorization for the lieutenant governor to prohibit the export of grain or its distillation, and the provision of annuities for disabled militiamen and for the widows and children of those killed. Amendments to the militia laws formed perhaps the most significant legislation, for these were intended to improve the efficiency of Upper Canada’s militia, an end Prevost had been urging on Sheaffe along with an expansion of the militia force. Under these amendments existing flank companies would be replaced by battalions of incorporated militia made up of volunteers who enlisted for the duration of the war. To attract volunteers a cash bounty was offered. Sheaffe claimed credit for this inducement but was disappointed that the amount authorized by the House of Assembly was only eight dollars. Drawing from the military chest, he raised the bounty to eighteen dollars and offered land grants to all ranks at the end of their service. Although it was expected that two or three battalions would be raised, only one was recruited in 1813, with its officers coming from regular regiments.

In his conduct of the war, Sheaffe consistently declined to take risks, a position which accorded with Prevost’s policy of a defensive war based on holding Montreal and Quebec. In March 1813 he exhorted Sheaffe to conserve his resources “for future exertion” and to adopt “activity and perseverance in the measures of defence, for which your present force and recent preparations are so well calculated.” A cautious and methodical commander, Sheaffe opposed John Vincent’s proposal to attack Fort Niagara that spring because not enough boats or Indians were available at the time. He sought to strengthen the defences of York but efforts there were abruptly cut short.

On 26 April an American fleet appeared west of the capital and the next day the invading force began landing, quickly establishing a beach-head. Sheaffe had about 700 regulars and militia and between 50 and 100 Indians with which to oppose some 1,700 United States regulars, supported by the guns of 14 ships. All he could do was fight a delaying action; nothing would have been gained by getting himself killed or captured, or by exposing his forces to heavy losses. After a brief engagement, he decided to retreat eastward to Kingston, destroying first a partially built ship, the marine stores, and the grand magazine. The town’s senior militia officers were left to make terms with the Americans. This was a sound military decision and perhaps the clearest evidence of its validity is contained in the reaction of the American secretary of war, John Armstrong: “We cannot doubt but that in all cases in which a British commander is constrained to act defensively, his policy will be that adopted by Sheaffe – to prefer the preservation of his troops to that of his post, and thus, carrying off the kernel leave us only the shell.” Unfortunately for Sheaffe, the post he had abandoned was the provincial capital, the home of such influential citizens as John Strachan*, William Allan, and William Chewett*, whose bitter criticisms of Sheaffe’s conduct and withdrawal helped to finish his career in the Canadas. Disagreement over his actions at York persists to the present day.

The problem of civilian loyalty increased following the American capture of York and during fighting on the Niagara peninsula in May and early June, at which time Sheaffe was still in Kingston. Prevost, who along with Commodore Sir James Lucas Yeo* had joined Sheaffe there, authorized him after his retreat to impose martial law if necessary in order to sustain his troops and control disaffected elements [see Elijah Bentley*]. Sheaffe saw no benefit in using martial law, however, and declined to employ this power, claiming that as president of the province he had no constitutional authority to do so.

After the American invaders had been forced back on the peninsula, Prevost removed Sheaffe from his civil and military commands, in which he was succeeded on 19 June 1813 by Major-General Francis de Rottenburg*. Four days earlier the members of the Executive Council then “resident” in Kingston, William Dummer Powell, Thomas Scott*, and John McGill*, had praised Sheaffe for his administration and for his part in the battle of York; apparently the general still had important friends in Upper Canada. Still, Prevost was so dissatisfied with him that he informed Lord Bathurst, the colonial secretary, that Sheaffe had “lost the confidence of the Province by the measures he had pursued for its defence.” In the opinion of William Dummer Powell, probably Sheaffe’s closest adviser on civil matters, he “was sacrificed to Ignorance & Jealousy of those who had not souls to comprehend his character in which truth & honor so much predominated as to give his Conduct the appearance of weakness.”

Sheaffe was subsequently ordered to take command of the troops in the Montreal District, a position which entailed little responsibility since there was no fighting taking place in that area. In July, Prevost nevertheless criticized him for “indifference” in the discharge of his duties and demanded his “active support.” The charge mystified Sheaffe. Although their correspondence does not make clear precisely how he was failing in his duties, Prevost was completely disillusioned with him. Though Sheaffe had been more assiduous than Brock in conducting the defensive war envisaged by Prevost, he had failed to keep Prevost well informed of his plans and thoughts and was unable to convince him that he was following his instructions. Even when faced with removal from his Montreal command, he feebly protested that Prevost was misinformed but made no attempt to set the record straight. On 27 September he was superseded by Prevost, who had returned to Montreal from Upper Canada, and was placed in charge of the reserve forces. Prevost, however, had already written to London about Sheaffe’s recall. Orders to that effect were sent in August 1813, but his departure was delayed until November.

On returning to England, Sheaffe and his family lived in Penzance and then Worcester, and in 1817 they moved to Edinburgh, where Sheaffe spent most of his remaining years. Although his appointment to the army staff on 25 March 1814 was later recalled and deferred, he was promoted lieutenant-general in 1821 and general in 1838. He had become colonel of the 36th Foot in 1829.

Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe was an experienced professional soldier who attempted to conduct the War of 1812 in Upper Canada in accordance with the defensive strategy of Sir George Prevost – an approach which undoubtedly suited Sheaffe’s cautious personality. It is, therefore, ironic that Prevost lost confidence in him for carrying out this policy, and that Brock, not Sheaffe, is known for the one battle Sheaffe won by a brilliant, offensive manœuvre.

A letter-book kept by Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe during the War of 1812 has been edited by Frank H. Severance and published as “Documents relating to the War of 1812: the letter-book of Gen. Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe,” Buffalo Hist. Soc., Pub. (Buffalo, N.Y.), 17 (1913): 271–381.

ANQ-Q, CN1-230, 29 janv. 1810. MTL, W. D. Powell papers. PAC, MG 23, HI, 4, vol.3: 1174; MG 30, D1, 27: 753; RG 8, I (C ser.), 230, 329, 677, 679, 922–23, 1170, 1218–21, 1694. Annual Reg. (London), 1851: 310–11. Boston, Registry Dept., Records relating to the early history of Boston, ed. W. H. Whitmore et al. (39v., Boston, 1876–1909), [24]: Boston births, 1700–1800, 197; [30]: Boston marriages, 1752–1809, 392. The correspondence of Lieut. Governor John Graves Simcoe . . . , ed. E. A. Cruikshank (5v., Toronto, 1923–31), 2: 364. Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank), vols.3–8. Gentleman’s Magazine, January–June 1855: 661. The life and correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock . . . , ed. F. B. Tupper (2nd ed., London, 1847), 18. Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). The Talbot papers, ed. J. H. Coyne (2v., Ottawa, 1908–9). Solomon Van Rensselaer, A narrative of the affair of Queenstown: in the War of 1812; with a review of the strictures on that event, in a book entitled, “Notices of the War of 1812” (New York, 1836). Burke’s peerage (1839), 938–39. DNB. G.B., WO, Army list, 1838–39. Hart’s army list, 1851. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 185–86. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving). D. B. Read, The lieutenant-governors of Upper Canada and Ontario, 1792–1899 (Toronto, 1900). Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical sketches of loyalists of the American revolution with an historical essay (2v., Boston, 1864; repr. Port Washington, N.Y., 1966), 2: 280–93. “State papers – U.C.,” PAC Report, 1893: 43–49. Richard Cannon, Historical record of the Thirty-Sixth, or the Herefordshire Regiment of Foot . . . (London, 1853), 118–19. J. M. Hitsman, The incredible War of 1812: a military history (Toronto, 1965). W. R. Riddell, The life of William Dummer Powell, first judge at Detroit and fifth chief justice of Upper Canada (Lansing, Mich., 1924), 112. C. P. Stacey, The battle of Little York (Toronto, 1963). W. B. Turner, “The career of Isaac Brock in Canada, 1807–1812” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1961). H. M. Walker, A history of the Northumberland Fusiliers, 1674–1902 (London, 1919). E. A. Cruikshank, “A study of disaffection in Upper Canada in 1812–15,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 6 (1912), sect.ii: 11–65. W. M. Weekes, “The War of 1812: civil authority and martial law in Upper Canada,” OH, 48 (1956): 147–61. Carol Whitfield, “The battle of Queenston Heights,” Canadian Hist. Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and Hist. (Ottawa), no.11 (1975): 10–59.

Cite This Article

Carol M. Whitfield and Wesley B. Turner, “SHEAFFE, Sir ROGER HALE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sheaffe_roger_hale_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sheaffe_roger_hale_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carol M. Whitfield and Wesley B. Turner |

| Title of Article: | SHEAFFE, Sir ROGER HALE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |