Source: Link

ALLAN, WILLIAM, businessman, militia officer, justice of the peace, office holder, judge, and politician; b. c. 1770 at the Moss, near Huntly, Scotland, son of Alexander Allan and Margaret Mowatt; m. 24 July 1809 Leah Tyrer Gamble in Kingston, Upper Canada; d. 11 July 1853 in Toronto.

William Allan’s family background and early training remain obscure. His lack of formal education and bad penmanship were sufficiently marked to cause him some concern in later life. He came to Canada about 1787, probably as a clerk for Robert Ellice and Company of Montreal, which was reorganized in 1790 as Forsyth, Richardson and Company. Since the Forsyth family was from Huntly, and John Forsyth* was a partner in the Ellice firm, it may have been through this family that Allan obtained his post in Canada.

In 1788 or 1789 he came to Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.), probably as a clerk under George Forsyth, head of the firm’s branch there. An important trans-shipment centre on the route to the upper Great Lakes, Niagara provided Allan with an excellent opportunity to learn all the details of the general merchant’s operations, the Indian trade, and garrison supply. In 1795 he applied for and received a town lot and an additional grant of 200 acres at Upper Canada’s new capital, York (Toronto). He moved there, becoming the local agent for Forsyth, Richardson and Company. Because of the firm’s Montreal location, excellent financial rating, and transatlantic trade connections, the agency gave Allan a lead over many rival merchants at the backwoods capital.

The move to York may have been something of a gamble: virtually only Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe* liked the site. But Allan’s relocation paid off. He almost immediately exchanged his town lot for a harbour-side property and in 1798 he was granted the adjoining water-lot for a wharf. About 1797 he had formed a partnership with Alexander Wood* in a general store. Wood, another Scottish emigrant, had worked for the Forsyth firm in Kingston before coming to York. The partnership lasted until 1801, when it was dissolved with some recrimination. Apparently the buildings were on Allan’s lot, for he ended up with the store and stock. As well, Allan purchased the debts due to the partnership, at what Wood claimed was far too low a price. Whatever the case, each went back into business for himself and both prospered. Most important, Allan was able to retain the agency for Forsyth, Richardson and Company.

As was usual at the time, he soon developed his own agencies in York’s growing hinterland centres. Although Laurent Quetton* de Saint-Georges was probably the leading merchant in York prior to the War of 1812, Allan quickly gained an excellent reputation. As the Church stated in his obituary, he “acquired the entire confidence of all classes of the community by his excellent habits of business, his punctuality in all transactions, and his perfect integrity.” Further, in May 1811, he entered into partnership with William Jarvie, forming William Allan and Company, which was dissolved in April of the following year.

The field of local government had quickly occupied Allan’s attention, particularly during slack seasons of trade when he had time on his hands. York formed part of the Home District, which was administered by local justices of the peace sitting in a court of quarter sessions. On 1 Jan. 1800 Allan joined their ranks and began to play a major role in district government. His work involved issuing various licences, including those for marriages and for shops and taverns. He was appointed to the onerous post of district treasurer on 9 April 1800 and his name appears on commissions for various public works. On 6 August he became collector of customs at York and district inspector of flour, potash, and pearl ash. (He was particularly familiar with potash for he had erected a potashery in 1800.) As well, in 1801 he succeeded William Willcocks* as postmaster at York and, commencing that year, Allan served as a returning officer in a number of provincial elections. In 1807 he presided over the election of Robert Thorpe*, whose traitorous remarks he reported to Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore.

Allan was also active within York’s small social élite. During the first decade of the 1800s he gained influential friends in official quarters, including two other Scots: Inspector General of Public Accounts John McGill* and Alexander Grant*, the provincial administrator (1805–6), who for a time lived with Allan. He was an early supporter of the Church of England. He and Duncan Cameron were the treasurers for the building fund of St James’ Church in 1803 and Allan was chief custodian for the expansion of the church in 1818. At the end of his term as people’s warden, an office he held from 1807 to 1812, he welcomed a new rector, the Reverend John Strachan*, another Aberdeenshire man who was to become a close friend. Allan had also married, in 1809. His wife, Leah Tyrer Gamble, a daughter of a surgeon with Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers, had wide family connections which can have done Allan’s career no harm; Samuel Smith*, for example, who later became provincial administrator (1817–18, 1820), was Leah’s uncle. Thus, though the War of 1812 would, in some ways, be a watershed in Allan’s career, he had laid the foundations of his future activities and influence well before the war, obtaining the respect and patronage of the local and provincial governing groups and building up a prosperous business.

Allan had been commissioned in the Lincoln militia in 1795 and three years later his lieutenancy was transferred to the York militia. In April 1812, on the eve of the war, he was promoted major of the 3rd York Militia, whose territory encompassed the town and its environs. With the beginning of hostilities in June the regiment’s flank companies, 120 strong, entered the garrison. Allan spent the winter of 1812–13 on garrison duty and escorting prisoners to Kingston. During the first capitulation of York, in April 1813, Major-General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe and the British regulars retreated to Kingston, leaving Allan and Lieutenant-Colonel William Chewett*, as the senior militia officers, to negotiate the terms of surrender, which provided that private property was not to be touched. Allan then became a prisoner on parole. He saw his store looted, but, with John Strachan, was successful in the keeping of order in the town. Justifiably, he went down as one of the heroes of the capitulation.

As a prisoner on parole Allan could not bear arms, but he was active as a government agent in curbing disloyalty and searching out enemy agents in the Home District. His zeal made a good impression on Judge William Dummer Powell*, an executive councillor and probably the leading figure in the government. Allan also impressed the Americans, who regarded him as “obnoxious,” and when the town was about to be captured for the second time, in July, he quickly fled. His store was looted again. The public declarations of sympathy for the enemy which had resulted from the occupations of York prompted such authorities as Allan and Powell to urge suppressive measures. In August, Allan, Strachan, and four others formed a committee of investigation, the findings of which led to the sentencing of such spokesmen as Elijah Bentley*. In May 1814 Allan was back on active duty after a prisoner-on-parole exchange. He saw no more action, however, although he was commander of the militia at the garrison until the fall of 1815.

During the war Allan was kept busy with the very profitable pursuit of supplying the garrison through the office of the commissary general. In all, the commissariat paid out more than £50,000 to York merchants, most of it to Laurent Quetton de Saint-Georges and Allan. The latter received at least £12,724, which represented a mark-up of about 100 per cent. Of course he also had claims for compensation for the damage to his store during the occupations and after the war he received 1,000 acres of land under the Prince Regent’s bounty. In 1815 he took his brother-in-law John William Gamble* as a partner in the store and they were later joined by another brother-in-law, William Gamble*.

The post-war years saw Allan’s gradual development from a leading merchant and holder of multiple local offices into the province’s principal financial figure. Politically his offices, in keeping with his growing reputation, were increasingly of provincial rather than local importance. But, in this sphere, Allan seemed to hold back, perhaps to ensure his flexibility in the economic enterprises that engaged his main attention. He always refused to run for elected office. When, in the election of 1800, the Upper Canada Gazette, the official government newspaper, stated that he would become a candidate for the York riding, he was furious. He complained to the government that if the assertion reached his commercial connections in Lower Canada uncontradicted, it would “very materially affect his Interests.” He therefore demanded that the editors, William Waters and Titus Geer Simons, be fired as government printers.

Though he was averse to seeking elective office, Allan continued and increased his early involvement in official administration. Probably because of his experience as a justice of the peace, in 1818 he was an associate judge along with the three justices of the Court of King’s Bench, William Dummer Powell, William Campbell*, and D’Arcy Boulton*, at the trial in York of two of the North West Company supporters involved with Cuthbert Grant in the murder of Governor Robert Semple* at Seven Oaks (Winnipeg). Later, in 1826, Allan was one of the justices sitting in the trial of the rioters who had destroyed William Lyon Mackenzie*’s printing-press. Allan was also in charge of the finances of such important public works as the rebuilding of the parliament houses in 1819–20. When they had to be rebuilt again after a fire, he assisted in 1826–29 in having the plans and estimates prepared. These can hardly have been profitable posts; however, when he was paymaster of the militia from 1818 to 1825, more than £28,000 passed through his hands, doubtless resulting in a fine commission. Also, he was gazetted in 1822 one of the commissioners for investigating claims for war losses and thus, with Alexander Wood and others, authorized the compensation for himself and his friends.

The fact that some of the offices he held enabled him to watch over his own interests may have made these services almost mandatory, but Allan’s public contributions merited recognition. His services were well appreciated within the “family compact” and in 1825 he was appointed to the Legislative Council. The following year, evidently with regard to the appointment of a new deputy postmaster general, Attorney General John Beverley Robinson* remarked to John Macaulay of Kingston, “He is really so very good a man & so upright & valuable a public officer, that everyone would be reluctant as well as yourself to interfere with any expectation he might reasonably indulge.”

In the years after his appointment to council, Allan gradually retired from the local offices that he had held for so many years: he ceased serving as postmaster and collector of customs in 1828 and as treasurer of the Home District the next year. Although deputies had done much of the work in these offices, the responsibilities must have consumed much time and conflicted with his banking interests, which were then at full tide. Also, the barbs of such radical reformers as William Lyon Mackenzie, who saw him as a political figure and accused him of monopolizing offices, must have been galling.

Allan’s business career underwent a complete redirection in the 1820s, but again this adjustment built upon earlier foundations. Like all pioneer merchants, he had acted as a banker, handling a considerable portion of the local exchange business for Forsyth, Richardson and Company. In 1818, the year after the Bank of Montreal was founded, he became its agent in York, a position he held for three years. The success of the Bank of Montreal and the need for banking services were quickly reflected in Upper Canada, where, as early as 1817, rival groups in York and Kingston [see Thomas Markland*] had begun to contend for the first bank charter. The York group was led initially by John Strachan and Alexander Wood rather than by Allan, with his Montreal connections, but by about 1819 he had taken over the leadership. Through various complex manœuvres in the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council, combined with the vital support of Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland, the York group appropriated the charter originally granted to Kingston, and in 1821 the Bank of Upper Canada was incorporated. Allan headed the subscription committee. By November of that year the necessary 4,000 shares, including a government purchase of 2,000 shares, had been subscribed. To start operations £20,000 in gold or silver had to be paid up, but the money was not forthcoming. The York group consequently had the bank’s charter amended to allow business to begin upon the payment of £10,000, Maitland gave royal assent to this legislation on 17 Jan. 1822, and by June enough capital had been paid up. Business commenced the following month. The bank did not, however, obtain the account of the province’s receiver general, John Henry Dunn, who continued to deal with Forsyth, Richardson and Company and the Bank of Montreal in matters of colonial finance and exchange, and used the Bank of Upper Canada only for transactions within the province. As a result of Allan’s increasing activity within the bank, which operated out of his store building until 1825, he sold his store interests in July 1822 to his partners, the Gambles, and “gave up all his concern in trade.”

The bank’s first directors in 1822 included George Crookshank, Provincial Secretary Duncan Cameron, Surveyor General Thomas Ridout*, Solicitor General Henry John Boulton*, and John Henry Dunn in addition to Allan and John Strachan. At the election for president, there was apparently some support for both Dunn and Crookshank (who was out of the province), but because of Allan’s mercantile success, experience with the Bank of Montreal, and hard work on behalf of the new bank, the directors elected him to the office. Except for 1825–26, when he did not stand because of a trip abroad and Crookshank held the presidency, Allan was re-elected annually until his resignation in 1835. Thomas Ridout’s son, Thomas Gibbs Ridout*, became the bank’s first cashier (general manager), a position he would hold for nearly 40 years.

The directorate, as William Lyon Mackenzie was constantly to remind it, comprised a “family compact” group. The reformers had early had representatives within the bank – Francis Jackson and William Warren Baldwin* – but as members of the founding group in 1821, these representatives were hardly in a position at the outset to quarrel with bank policy. The image of the bank as a government body was reinforced in January 1823 by legislation which authorized the lieutenant governor to appoint 4 of the bank’s 15 directors, of whom a large number were already executive or legislative councillors. Banking had not yet become a major political issue, however, and Allan received the cooperation of the House of Assembly on banking matters. In 1823, in an attempt to align capitalization with the exigencies of the province’s economy, the capital of the bank was reduced from £200,000 to £100,000. The following year it achieved a monopoly on note issuing in the province through an act which required, for five years, all banks operating there to redeem their notes in Upper Canada. The bank, however, did not operate without internal friction. In 1825 a group headed by William Warren Baldwin and Thomas Gibbs Ridout made a determined effort to dominate the board of directors, evidently during Allan’s absence. Although the group canvassed extensively for votes, especially in Niagara and Kingston, it was soundly defeated.

Allan’s caution and sound judgement made him a very successful banker and contributed to the Bank of Upper Canada’s prosperous situation at the end of the 1820s. From 1824 it had paid annual dividends of eight per cent on paid-up capital, plus some bonuses. Following the expiry in 1829 of the note redemption act, the bank became engaged in a specie war with the Bank of Montreal, which had sent its agents back into York and Kingston, in part to take advantage of imperial spending on the Rideau Canal. Each bank purchased the other’s notes with the intention of demanding payment in specie upon presenting the notes. Allan played his cards boldly, sending Thomas Gibbs Ridout to Montreal to arrange weekly shipments of specie. In the end, Allan later informed Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne*, he and his bank “met the exigency triumphantly & were above all difficulty.” The banks reached an agreement whereby the Montreal bank withdrew all its Upper Canadian agents except Henry Dupuy at Kingston and acted as agent in Montreal for the Upper Canadian bank; Allan subsequently used his personal friendship with Peter McGill, an influential director of the Bank of Montreal, to maintain smooth relations. The Bank of Upper Canada benefited too from the increasing number of public works in the province, which were financed by government debentures. These were bought by the bank at six per cent and negotiated in Montreal, London, or New York. Early in 1833 Allan secured for the bank the business of the British Treasury in Upper Canada, including the lucrative commissarial business at Kingston.

By the opening of the 1830s the bank, despite its success, was confronted with continuing internal dissent, political opposition, and new competition. In a colony that was undergoing a rapid increase in population as a result of immigration and that was heading into boom times, Allan’s strict policies on the function and expansion of the bank were becoming increasingly unpopular. As a merchant running a bank, Allan regarded it as a centre for financial transactions such as the making of loans on, or the discounting of, promissory notes and bills of exchange; the handling of coin and bullion; and the purchase and resale of government debentures. The bank’s circulation of capital in the form of loans to merchants [see James Crooks] constituted its main source of profit. In 1837 Thomas Gibbs Ridout reported that about one-third of the bank’s business had been enabling “the Merchant to transact through its medium and assistance his remittances to other Countries,” for which service a premium was charged on the normal rate of exchange. According to Allan in 1831, the negotiation of bills on Montreal and New York “in aid” of the wheat, flour, and general export trade averaged £500,000 annually. The bank maintained deposits of capital in those places and in London in order to sell bills on the markets there at any time of the year; in New York it dealt regularly with Prime, Ward, and King, and in London with Thomas Wilson and Company.

The bank had opened agencies at Kingston (1823), Niagara (1824), Montreal (1829), and Cobourg (1830). In 1830, however, Allan advised John Macaulay, a close friend and the bank’s Kingston agent, of his preference for “keeping within bounds on the secure side,” thus avoiding too rapid growth that might later necessitate the contraction or withdrawal of agencies. Accustomed to running his own business, Allan was ready in the interest of prompt action to do what he conceived was “right & safe” without referring every decision to the directors. He could not, however, carry them on all points. He preached restraint to a board which supported his management but which, as early as 1823, contained a majority out of sympathy with his policies. Allan decried his associates’ involvement with speculative ventures. His pessimism was on occasion borne out, as in the reckless entrepreneurial practices and financial collapse in 1833 of James Gray Bethune*, the bank’s cashier at Cobourg. Losses resulting from such failures were absorbed without harm to the bank’s reputation. But even the success of the bank became controversial, and serious discontent developed among businessmen who wanted to break the banking monopoly of the York élite and to use the bank more as a source of investment capital.

In 1830 Allan faced concentrated, politically motivated opposition. William Warren Baldwin and his son Robert, supported by William Lyon Mackenzie, sought disclosure of shareholdings and a full reporting of the bank’s affairs. Allan resisted the demands of a House of Assembly committee headed by Mackenzie, but failed to counter effectively Robert Baldwin’s charges there in February that the bank acted as a “dangerous engine of political oppression” and that notes had been blackballed and discounted “from political motives.” This challenge was followed in June by an unsuccessful bid, originating within the same committee and led by the Baldwins, to obtain disclosure by securing the election of a sympathetic director. Allan, who was observed on such occasions to express himself heatedly in a “rich Aberdeen brogue,” believed that George Ridout* and possibly his brother Thomas Gibbs Ridout had also been involved, apparently in the hope of getting George on the board.

Balked in this area, political opponents of the Bank of Upper Canada regrouped around John Solomon Cartwright* and other Kingston businessmen seeking a bank charter. This attempt attracted wide support, since it appealed to those who favoured the American system of numerous banks as well as to those who believed that the York bank deliberately retarded development in order to preserve a profitable monopoly. Allan’s response was dictated by his policy on expansion and by political necessity. He believed that safe banking required hard money – paper currency “of a proper value with Gold and Silver.” In his opinion this monetary objective could best be achieved by a single bank, with adequate capital, establishing branches throughout the province. To achieve expansion on these terms, the Bank of Upper Canada now needed additional capital, but Allan was in a stalemate with the assembly, whose authorization was needed. So long as Allan and other members of the Legislative Council blocked a charter for the Kingston bank, the assembly would refuse to restore the Bank of Upper Canada’s capital to £200,000. In late 1830 Allan appears to have initiated a bid to secure government support for capitalization when he encouraged John Macaulay to discuss the matter with Peter Perry, a member of the assembly, and to “pursuade” Cartwright to write to Solicitor General Christopher Alexander Hagerman*, presumably to find a resolution to the political impasse. Two years later bills of incorporation, for the Commercial Bank of the Midland District, and capitalization, for the Bank of Upper Canada, were passed. In contrast to Allan, John Strachan, who no longer sat on the board but reflected the thinking of many directors, did not fully recognize a need to relate paper to metallic currency; he argued for the careful expansion of the Bank of Upper Canada but believed that Allan’s inhibitions had hurt it.

While Allan settled in to do business with the Commercial Bank on the basis of “amiable” rivalry, William Lyon Mackenzie carried to the Colonial Office his opposition to the privileged position of all chartered banks. He convinced British officials that the bank acts passed in 1832 did not contain adequate safeguards and brought home rumours in 1833 of their impending disallowance. This threat brought Allan into community of purpose with other businessmen in Upper Canada: he lent his weight to calming alarm and to a successful campaign to persuade the British authorities to withdraw their opposition. Yet this victory over “scandulous misrepresentation” and deception did not bring lasting peace.

Once the Kingston bank was chartered, Allan had informed William Hamilton Merritt* in December 1831, “common Justice” must open the door to others and he promised to support Merritt’s proposal for a bank at St Catharines and “all future applications that appear reasonable.” By 1834 the Bank of Upper Canada itself had established new branches, at Hamilton and Brockville, as well as agencies at Amherstburg, Penetanguishene, Prescott, and Bytown (Ottawa). Private partnership banks were also making their appearance, one of which, George Truscott’s Agricultural Bank, opened in Toronto in 1834 and paid interest on deposits, thus setting a controversial precedent which other institutions followed of necessity. Allan deeply distrusted Truscott and his methods of banking, and the two soon became locked in a specie war. Truscott, who had heard rumours that Allan’s board did not support his campaign wholeheartedly, characterized the Bank of Upper Canada in 1835 as a “discreet old lady” and attacked the integrity of its president with biting sarcasm.

Meanwhile, Allan was becoming progressively more dissatisfied in the bank. In 1832 death in his family and his own serious illness had left him “very much depressed.” He pondered about building a small cottage and taking a trip abroad, and suggested that “if spared” he would in a year’s time have “left all this,” including the bank, “for others.” He rallied, but felt increasingly isolated within a bank board which, he confided to John Macaulay, no longer supported him fully and undervalued his service.

During the winter of 1834–35 Allan was equally frustrated in his dealings with the government. He believed the connection had outlived its usefulness to the bank, but Lieutenant Governor Colborne and the government directors had blocked his attempt to have the government’s shares sold, thus forcing him to face continued criticism from the bank’s political opponents. His objections to John Henry Dunn’s plan to circumvent the bank by selling debentures directly on the British market were also set aside. Allan had argued that if the interest on the debentures was paid in Upper Canada, capital and capitalists would be attracted to the colony. As well, he knew that the position of the Bank of Upper Canada as the intermediary for such internal financing would be altered if, along the lines of Dunn’s plan, interest was paid in England. Weary of the struggle, he resigned as president in 1835.

Allan saw Dunn as the leading presidential candidate and the one favoured by Colborne and the government directors. He nevertheless disliked, thoroughly, Dunn’s policies on public borrowing and his attempts to curry political and popular favour. He thought better of John Spread Baldwin, a former director, but Baldwin was not a member of the board and thus received few votes. The directors subsequently elected the pliable William Proudfoot*. Allan had no intention of accepting a secondary role as a director of an institution which, he believed, soon deviated “very much” from his “system” and “management.” After he had resigned, the bank experienced increasing subordination to political interests, which contributed much to its ultimate decline [see Robert Cassels*; Thomas Gibbs Ridout]. Allan nevertheless established a working relationship with it in the interest of such ventures as the Welland Canal Company, the Canada Company, and the British America Fire and Life Assurance Company, his other major corporate concerns.

The Welland Canal Company had been chartered in 1824 under the aegis of William Hamilton Merritt. The next year Allan invested the £250 necessary to become a director of the company, and he was duly elected along with such leading provincial figures as John Henry Dunn and John Beverley Robinson. In time Allan became vice-president. Convinced of the value to the Canadas of the inland water-way, he was one of those to whom Merritt turned for support when he approached the Bank of Upper Canada, which by statute in 1824 became treasurer for the canal company, for loans for the canal. The bank refused to lend the company any money directly, but did lend sums to its directors on their personal security. Although the bank purchased debentures from the government, with the money going to the company, these were resold. In 1830 Allan warned Merritt that a canal project undertaken in the public interest offered insufficient inducement to private financing. And, while the sums he sought from the bank might be of the “utmost consequence” in the short term, Allan added, “It is not a little [money] that does for your wants – it is large sums that will only do for you.” After he withdrew from the boards of both the bank and the canal company, Allan continued his interest, at least until 1837, in Merritt’s efforts to raise money.

In 1829 Allan agreed to become “for a limited period” one of the two Upper Canadian commissioners appointed by the Canada Company to replace John Galt*. Set up to sell a large tract of land along Lake Huron, as well as lots elsewhere in the province, the company had been badly managed by Galt, and the directors in London wanted a complete reorganization. Allan initiated the transfer of the company’s Upper Canadian headquarters from Guelph to York, where he assumed responsibility for managing the scattered former crown reserves that had been transferred to the company in 1825. The other commissioner, Thomas Mercer Jones*, took charge of sales in the Huron Tract. As part of the reorganization, Allan moved quickly to deal with outstanding claims, re-establish public trust, and institute a complete review of the company’s books. He warned the company that giving his full time to its affairs would be “rather too much to be expected constantly,” but he did so as long as the review was in progress. He was confident of his managerial skills, although less so when the London directors asked him to produce a full report of Canadian operations.

Allan feared that his analysis of possible courses of action in the Huron Tract was “too tedious and lengthy” for the directors. His report of September 1829 nevertheless demonstrated the considerable thought that he, a major landowner on his own account, had given to the problems of immigration and settlement and to the work of such successful promoters as Colonel Thomas Talbot and Peter Robinson*. Allan’s advice to the directors was clear. The development of crown reserves offered immediate profit, the Huron Tract the best future prospects. The Canada Company’s stock was depressed for two reasons: shareholders misunderstood the kind of investment involved and they were hesitant “in advancing the capital necessary.” If the shareholders were to realize the excellent, long-term financial potential offered by the venture, Allan argued, they should put up the full amount of their instalment payments as well as assume a large proportion of the expenses of the early years. To encourage investment, he recommended the payment of a dividend tied to land sales by the company.

In February 1830 Allan was shocked to find that the directors were considering dissolution of the company at a time when he had committed his reputation to its renewal. It survived, but Allan does not seem to have given the company his full attention. He had obtained a portion of its Upper Canadian business for the Bank of Upper Canada and continued to interest himself, on the company’s behalf, in financial matters and in questions of monetary exchange. As well, from about 1834 and possibly earlier, the Canada Company’s offices in York were housed in premises owned by Allan. In 1835 the directors signified their appreciation of his services by increasing his salary by £200 sterling. By 1839, however, they were once more wishing for new direction in their affairs in Upper Canada. Frederick Widder* was sent out that year to replace Allan, who retired from the company in 1841.

Allan’s last major directorship was with the British America Fire and Life Assurance Company. Founded in 1833 to fulfil the need of obtaining fire and navigation insurance at reasonable rates in York, the company had William Proudfoot as its first governor and Allan headed its subscription committee. Allan’s brother-in-law Thomas William Birchall became general manager in 1834, and two years later, after Proudfoot had gone to the Bank of Upper Canada, Allan was elected governor. The business, of which he remained governor until his death, was soundly underwritten and proved highly successful.

In addition to these business and financial institutions, Allan was for some time interested in the development of transportation systems. In 1827 he served, as a legislative councillor, on a government committee dealing with navigation on the St Lawrence River. By 1835 he believed that too much public funding was going to the St Lawrence canals and that some should be appropriated to inland water-ways. During the 1830s he also became interested in railways, but in that new field his achievements as a promoter fell far short of his successes elsewhere as a financier.

When the City of Toronto and Lake Huron Rail Road Company was organized in 1837 he was elected to its board of directors with the greatest number of votes, thus becoming president. Before adequate funds could be raised, however, the depression of 1837 set in and plans to build the railway had to wait for the return of prosperity in the mid 1840s. Allan and his associates revived the project in December 1844. Almost immediately their scheme was confronted with energetic opposition from the principal promoters of the Great Western Rail-Road, Sir Allan Napier MacNab* in Hamilton and Peter Buchanan in London, England. As well, Allan’s entrepreneurial role within the Toronto company was to be successfully challenged by John Wellington Gwynne* and Frederick Chase Capreol*, whose aggressive promotional tactics contrasted sharply with Allan’s cautious, methodical management. In 1847 his ill-timed prosecution of George Crookshank for defaulting on stock payments was publicly criticized and allowed Gwynne and Capreol to come to the fore. Under the latter’s direction the project eventually led to the construction of the Toronto, Simcoe and Huron Union Rail-Road (later renamed the Northern Railway), which became a profitable enterprise for both its shareholders and the developers of the city of Toronto.

Allan was unanimously elected first president of the Toronto Board of Trade when it was initially founded in 1834. By that time, despite the decline of the “family compact” in politics, he had become the unquestioned doyen of Upper Canadian business. Allan’s withdrawal from mercantile business in 1822 and his corporate involvement for more than 20 years did not mean that he gave up all his private interests or terminated the excellent network of connections that he had developed over the years. Thus he was still engaged in various personal investments and when the British-based Bank of British North America was founded in 1836, he became a shareholder. A number of his activities were of the type that would now be carried on by a lawyer or trust company, for he was an agent, trustee, financial adviser, realtor, and estate administrator or executor. The management of estates in Upper Canada was one of his most time-consuming tasks, and could frequently be complicated by the existence of landholdings and heirs in England and Scotland. The tangled affairs of the estate of William Berczy*, who died in 1813, took until 1841 to settle, the major creditor being Forsyth, Richardson and Company. Settlement of the estate of Chief Justice Thomas Scott*, for which Allan and John Strachan were co-executors, dragged on for a decade after Scott died in 1824. Thus, while Allan may be best known as a financier, his work as a trustee also occupied a great deal of his time and energy.

In carrying out these duties he had working with and advising him a wide network of friends and associates. Some of these, such as John Macaulay, were personal friends as well as close business associates. For another valuable Upper Canadian connection, Colonel Thomas Talbot of the London District, Allan handled investments and Talbot, in return, advised him on western land purchases. Beyond Upper Canada, Allan’s correspondents included Peter McGill, in Montreal, and a variety of persons in England. Allan helped the family of John Graves Simcoe with its Upper Canadian investments: between 1832 and 1853 he bought or handled the sale of much of its landed property in the province. As well, he took care of various business matters for retired officials and officers, such as former Surveyor General Sir David William Smith* and Robert Pilkington*. His most influential British correspondent, however, was Edward Ellice*, whom he had known since his early days in the mercantile business. Ellice probably secured for Allan his commissionership with the Canada Company. As Ellice’s attorney in Upper Canada, Allan attended to land speculation and financial matters; in 1845 Ellice advised him, “I am perfectly satisfied that you do for me, as you do for yourself, in these matters, & thank you sincerely for your kindness & attention to them” – the sort of expression that Allan received from many. Thus, even beyond Upper Canada, he came to be regarded as a financial expert on the colony.

Allan’s own land speculations occupied a good deal of his time. The amount of land that he held at different times is impossible to estimate, but for some 60 years he was continuously involved in the land market, dealing in both wild land and areas which he hoped to develop. By 1829 he had held land in townships in almost every district of the province. An idea of the size of his holdings may be judged from the request he made to John George Howard* in 1841, noted in Howard’s diary, “to get the List of 20 thousand acres of Land to sell for him.” Not all his speculations were immediately successful. In 1832 he attempted to found a recreation and cottage community at Niagara Falls in association with some of the most astute investors in Upper Canadian lands, including Thomas Clark* and Samuel Street*. Sales for the “City of the Falls” failed to come up to expectations and by 1837 the property was being divided among the proprietors. Allan was still winding up his part in 1850 through the agency of Thomas Clark Street*.

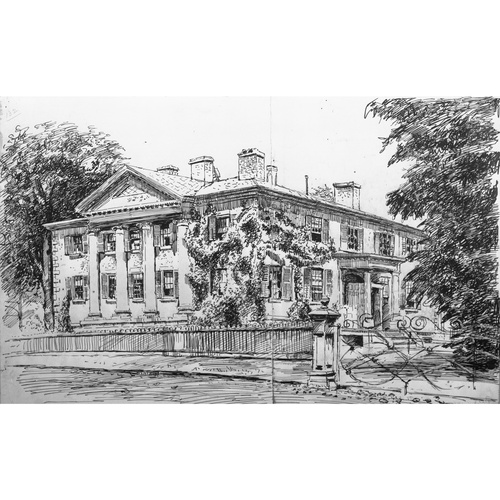

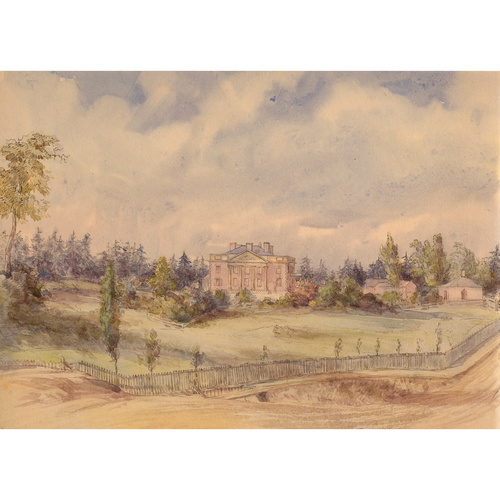

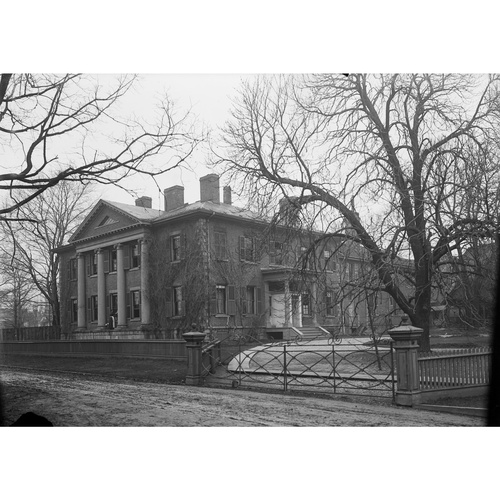

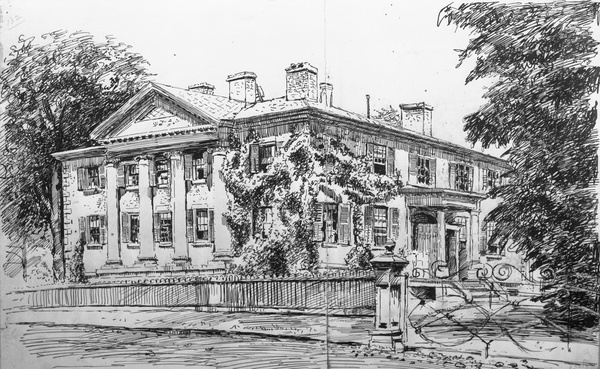

His most valuable land was his own park lot in York, which he had purchased in 1819. Subdivided after Allan’s death by his son, George William, the land stretched roughly a mile and a half from present-day Richmond Street to Bloor Street in Toronto, running west from Sherbourne Street to about Jarvis Street. On this wooded lot, in about 1828, Allan built a large house, Moss Park. His family life there, unfortunately, was tragic. The death in 1832 of his eldest daughter, “lovely” Elizabeth, was, in the opinion of Mrs Anne Powell [Murray*], “lamentable proof of the insufficiency of wealth to promote or rather confer happiness; Allan from a state of indigence is one of the richest men in the community; his house as you know is a Palace; its splendour has become desolation.” Nine of Allan’s eleven children died before the age of 20, many of them of the consumption that carried off his wife in 1848 and probably his last daughter in 1850. Only one son, George William, survived him.

During the mid 1830s Allan appears to have played a diminishing role in politics, the result, perhaps, of family circumstances, his withdrawal from the Bank of Upper Canada, and the waning political power of such veteran associates as John Strachan. In March 1836, however, Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head* got into a quarrel with his Executive Council over the constitutional question of whether or not he had to consult that body, and the entire council resigned. Allan, with three other legislative councillors, Augustus Warren Baldwin*, John Elmsley*, and Robert Baldwin Sullivan, was called by Head to sit on his new council, and he accepted as his duty. Special arrangements were made so that he would act as administrator of the province if the governor were absent or incapacitated. Again, the honour showed Allan’s position in the community. Head described him privately as “an excellent honest honorable man of high character and sound principles” but without “much talent or education” and “led a little by the Scotch.” Sir George Arthur, Head’s successor in 1838, would look to more politically oriented survivors of the old tory group such as John Beverley Robinson and John Macaulay for advice, so that Allan’s executive posting did not keep him at centre stage. His authority also declined within the Legislative Council, to which he gave a stern warning in 1839 of the likely results of uncontrolled public spending and borrowing. He pointed out that the public debt, which exceeded £1,200,000, was absorbing all revenue and that there was no provision to repay capital. Knowing that he was in a minority on this issue, he acted not to influence policy but to record his “sentiments” in anticipation of the “consequence of a fictitious credit.” His analysis echoed arguments on monetary policy and financial management that he had used six years earlier in banking.

As a major landholder and Canada Company commissioner, Allan also maintained a clearly defined position on land policy. In council debate in 1840 over free grants to immigrants, he and Richard Alexander Tucker*, the provincial secretary, spoke out for the large landholders bent on preserving their market by preventing areas of crown land from being opened up to settlement at either low prices or by free grants. Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson* (later Lord Sydenham), however, believed that Allan was out of touch with the needs of a developing province and suspected him “of having the Canada Company a little too much in his mind to give an unbiased opinion.”

Allan served with greater effectiveness on a number of special commissions, such as those formed to examine persons arrested for high treason after the rebellion of 1837–38, to investigate in 1838 the sexual conduct of George Herchmer Markland*, the province’s inspector general of public accounts, and to inspect in 1839–40 the administration of public departments. As a committee chairman on the last commission, Allan was responsible for the examination of eight departments, notably those of Crown Lands Commissioner Robert Baldwin Sullivan and Receiver General John Henry Dunn. Allan’s committee focused on the totally inadequate method of accounting in Sullivan’s office and recommended, in its place, the double-entry system with which Allan was familiar as a businessman. As for the Receiver General’s Department, Allan, who was already deeply suspicious of Dunn’s unprecedented powers in raising public loans, pressed for a careful distinction between his public and private transactions. Although Dunn intervened personally to limit Allan’s investigation, Allan had had adequate time to show that he still possessed a flair for incisive analysis in matters of finance. Dunn’s department and others were later reorganized under Lord Sydenham.

Allan remained on the Executive and Legislative councils until the union of the Canadas in February 1841 and then retired from politics. He was, however, still to be found chairing meetings of the tory British Constitutional Society during the 1840s, and in 1849 was a vice-president of the British American League [see George Moffatt*]. Two years later he supported John Strachan in the founding of Trinity College and was a member of its board when he died. As well, he sat on the board of the Church Society, which handled funds for the Anglican diocese of Toronto. Outside the church, however, his charitable activities appear to have been limited; in 1836 he had been instrumental in organizing a local St Andrew’s society, of which he became first president.

Allan was fortunate in enjoying “a long life of almost uninterrupted health”; after being in a weak state for some time he died “at last from sheer exhaustion” on 11 July 1853. He was probably the oldest inhabitant of the city, the only person who could speak of its earliest history from personal knowledge. How much wealth he left is unknown. In his very business-like will he left everything to his son, George William, after making minor bequests to relatives, the church, and local charities.

At the end of his life Allan became somewhat crotchety. Charles Morrison Durand, a Hamilton lawyer, later recalled his demeanour as “proud and austere, at least to strangers.” At the same time he had outlived many of the antagonisms of the 1820s and 1830s. When he died, the Toronto Mirror, the reform journal published by Charles Donlevy, assessed his political career: “His politics we judge with leniency. Connected with the early history of the Province and the compact that ruled its destinies, he belonged to a school that has become obsolete and incapable of renovation. The liberal policy of a more enlightened and progressive period was unknown in his day, and it would be unjust to subject his conduct to the rules of modern improvement. We believe, however, that neither by natural nor acquired abilities he was adapted for political life, and his errors he only shared in common with his more gifted associates.”

Allan, though always identified with the “family compact,” was never a member of the inner circle of government. But for the crisis precipitated by Sir Francis Bond Head, he might never have sat on the Executive Council. Before his rise to prominence as president of the Bank of Upper Canada, contemporaries as far apart politically as John Beverley Robinson and William Lyon Mackenzie agreed in portraying Allan as an administrator rather than an initiator of government policy.

His reputation rested on his success in business. As his obituary in the Church correctly noted, “Whatever success he had in life was due chiefly to his persevering industry, for he hazarded little in doubtful enterprises and had no fondness for speculation.” He did a great deal for the successful development of Ontario’s first corporations and set standards of management which few contemporaries could equal. At the height of his career, businessmen were willing to invest in the Bank of Upper Canada on the strength of his reputation and, in his old age, he was remembered for his wealth. Some of his associates, such as William Hamilton Merritt, also gave Allan credit for more than an eye for profit. Within the context of his admittedly rigid views on business and development in Upper Canada, he appears to have had a genuine concern for his adopted country. Possibly he saw the province in much the same light as he had the Bank of Upper Canada. For each he argued for expansion tempered by enough fiscal restraint to ensure independence from outside control.

The largest collection of Allan papers is at the MTL. Because he was prominently involved in public life and business for more than 50 years, material on Allan can be found in most collections pertaining to early Toronto. For this reason only the most important sources consulted are listed.

AO, MS 74, packages 11–15, 30, 34; MS 78; RG 22, ser.155, will of William Allan. MTL, J. G. Howard papers, sect.ii, diaries, 1834, 1841; misc. accounts, “Memorandum of papers burnt,” 88; S. P. Jarvis papers; W. D. Powell papers, A99 (M. B. Powell [Jarvis] corr.): 138–39. PAC, MG 24, E1: 620–1797; RG 1, L3, 2: A3/39; 3: A4/40, A5/18; 4: A8/1; RG 5, A1: 5291–92, 19002–5, 22083–85, 27080, 29004–9, 29022–23, 29116–18, 30700–4, 31823–24, 32175–78, 37790–92, 38244–45, 38792–95, 71640, 82370–72, 82614, 82674–84, 83514–16, 83831, 117145–48; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: 181, 245, 407, 525, 670–71, 678. PRO, CO 42/393: 273 et seq.; 42/415: 2, 4, 6, 20, 22, 24, 28–29. Toronto Land Registry Office (Toronto), Abstract index to deeds, 581, park lots 4–5. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1841, app.F; 1843, app.I. The correspondence of the Honourable Peter Russell, with allied documents relating to his administration of the government of Upper Canada . . . , ed. E. A. Cruikshank and A. F. Hunter (3v., Toronto, 1932–36), 3: 15–16. Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank), vols.2–9. “Grants of crown lands in U.C.,” AO Report, 1929: 121, 157, 162. “Journals of Legislative Assembly of U.C.,” AO Report, 1911: 92, 127–28, 216; 1912: 419; 1913: 230–31; 1914: 60–63, 543, 732–33, 752, 755. “Minutes of the Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for the Home District, 13th March, 1800, to 28th December, 1811,” AO Report, 1932: 3. The parish register of Kingston, Upper Canada, 1785–1811, ed. A. H. Young (Kingston, Ont., 1921), 108, 135, 149. Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood), 1: 400; 2: 84, 189–90, 192, 194. The Talbot papers, ed. J. H. Coyne (2v., Ottawa, 1908–9). Town of York, 1793–1815 (Firth); Town of York, 1815–34 (Firth). U.C., House of Assembly, App. to the journal, 1835, 1, no.3; 1836, 3, no.106; 1837–38, 1: 212–34; 1839–40, 1, pt.i: 308–19; 2: vi-vii; Journal, app., 1829: 43–44 (2nd group); 1830: 21–48; 1831–32: 96–99; 1832–33: 75; 1833–34: 162–74, 213–14; Legislative Council, Journal, 1828–40, especially 1831–32: 51; 1839: 204–5. “Upper Canada land book B, 19th August, 1796, to 7th April, 1797,” AO Report, 1930: 102. “Upper Canada land book C, 11th April, 1797, to 30th June, 1797,” AO Report, 1930: 151. “Upper Canada land book D, 22nd December, 1797, to 13th July, 1798,” AO Report, 1931: 145. Church, 14, 21 July 1853. Colonial Advocate, 19 Aug. 1814; 7 April, 23 May 1825; 25 Feb. 1830–21 Dec. 1833, especially 10 June 1830, 6–27 May, 3, 10 June 1833. Daily Leader (Toronto), 12 July 1853. Toronto Mirror, 15 July 1853. Upper Canada Gazette, 30 April, 4 June 1821; 11 July 1822. York Gazette, 11 May 1811, 28 July 1812. Chadwick, Ontarian families, 1: 79–80. Toronto directory, 1833–51. Lucy Booth Martyn, The face of early Toronto: an archival record, 1797–1936 (Sutton West, Ont., and Santa Barbara, Calif., 1982). The defended border: Upper Canada and the War of 1812 . . . , ed. Morris Zaslow and W. B. Turner (Toronto, 1964). Denison, Canada’s first bank, vol.1. Charles Durand, Reminiscences of Charles Durand of Toronto, barrister (Toronto, 1897), 130–31. B. D. Dyster, “Toronto, 1840–1860: making it in a British Protestant town” (1v. in 2, phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1970). “Historical sketch of the British America Assurance Company,” Canadian annual review of public affairs, ed. J. C. Hopkins (Toronto), 1911, Special supplement . . . : 96–104. M. L. Magill, “William Allan: a pioneer business executive,” Aspects of nineteenth-century Ontario . . . , ed. F. H. Armstrong et al. (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974), 101–13. Middleton, Municipality of Toronto. Robertson’s landmarks of Toronto, 1: 251–53, 366, 561; 6: 275, 300. V. Ross and Trigge, Hist. of Canadian Bank of Commerce, vol.2. Scadding, Toronto of old (1873; ed. Armstrong, 1966). T. W. Acheson, “The nature and structure of York commerce in the 1820s,” CHR, 50 (1969): 406–28. H. G. J. Aitken, “The Family Compact and the Welland Canal Company,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 18 (1952): 63–76. P. A. Baskerville, “Entrepreneurship and the Family Compact: York–Toronto, 1822–55,” Urban Hist. Rev. (Ottawa), 9 (1980–81), no.3: 15–34. R. M. Breckenridge, “The Canadian banking system, 1817–1890,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 2 (1894–95): 105–96. L. F. [Cowdell] Gates, “The decided policy of William Lyon Mackenzie,” CHR, 40 (1959): 185–208. E. C. Guillet, “Pioneer banking in Ontario: the Bank of Upper Canada, 1822–1866,” Canadian Banker (Toronto), 55 (1948), no.1: 115–32. L. B. Jackes, “Toronto’s first bank,” Toronto Sunday World, 26 March 1922; repub. in Canadian Paper Money Journal (Toronto), 17 (1981): 71–74. M. L. Magill, “William Allan and the War of 1812,” OH, 64 (1972): 132–41. R. C. B. Risk, “The nineteenth-century foundations of the business corporation in Ontario,” Univ. of Toronto Law Journal (Toronto), 23 (1973): 270–306. Adam Shortt, “The early history of Canadian banking,” “The history of Canadian currency, banking and exchange . . . ,” and “Founders of Canadian banking: the Hon. William Allan, merchant and banker,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal, 5 (1897–98): 1–21; 8 (1900–1): 4–6, 227–43, 305–26; 30 (1922–23): 154–66. C. L. Vaughan, “The Bank of Upper Canada in politics, 1817–1840,” OH, 60 (1968): 185–204.

Cite This Article

In collaboration, “ALLAN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allan_william_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/allan_william_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration |

| Title of Article: | ALLAN, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |