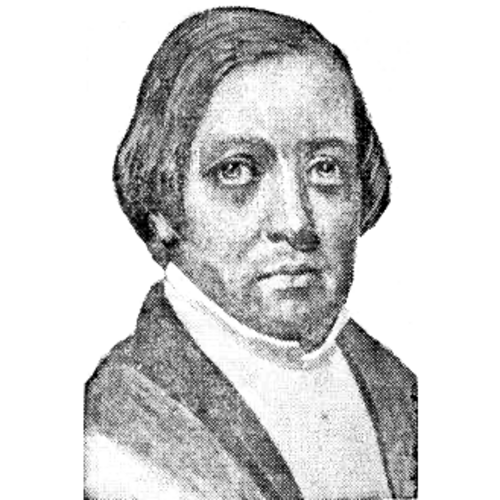

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SULLIVAN, ROBERT BALDWIN, lawyer, office holder, politician, and judge; b. 24 May 1802 in Bandon (Republic of Ireland), son of Daniel Sullivan and Barbara Baldwin; m. first 20 Jan. 1829 Cecilia Eliza Matthews, and they had a daughter; m. secondly 26 Dec. 1833 Emily Louisa Delatre, and they had four sons and seven daughters; d. 14 April 1853 in Toronto.

Robert Baldwin Sullivan’s father was an Irish merchant, and his mother was a sister of William Warren Baldwin*. The first member of Robert’s family to come to York (Toronto), Upper Canada, was Daniel, his eldest brother, who became a law student under Baldwin and lived with another uncle, John Spread Baldwin. The rest of the family immigrated in 1819 and the ambitious Daniel Sr established himself as a merchant in York, dealing in soap and tobacco. After a promising beginning, the Sullivans’ aspirations were dashed. In 1821 Daniel Jr died; the following year his father’s death left Robert as the head of the family. Once again the extended family lent its support; in 1823 William Warren Baldwin placed his nephew on the books of the Law Society of Upper Canada and secured for him a position as librarian to the House of Assembly. Having received a solid education in private schools in Ireland, Robert excelled in his law studies and was called to the bar in Michaelmas term 1828.

Sullivan first took an active role in politics during the exciting provincial election of 1828, as a campaigner for his uncle. Symptomatic of the increasing organization of the reform movement, John Rolph* had arranged W. W. Baldwin’s candidacy in his home riding of Norfolk, though Baldwin remained in York to aid in the campaign of Thomas David Morrison. Sullivan went to Vittoria to represent his uncle, who was elected, he noted, largely because of Rolph’s influence. Sullivan subsequently returned to the capital and took part with Baldwin and his son Robert in Morrison’s challenge to the return in York of their arch-foe, tory John Beverley Robinson*. He then gave counsel and support to Rolph in his legal defence of Francis Collins*, a supporter of his cousin Robert. Despite the fact that Morrison was defeated and Collins found guilty of libel, Sullivan’s considerable legal talents did not go unnoticed.

His future looked bright indeed, but not in the provincial capital. He returned to Vittoria, apparently determined to settle there and take over the law practice vacated by Rolph as a result of his move to Dundas. Shortly afterwards, in early 1829, he married a daughter of John Matthews*, a reform colleague of Rolph’s. But once again, after a promising beginning, successive tragedies unravelled Sullivan’s personal life: on 20 Dec. 1830, six months after the birth of their daughter, Sullivan’s wife died; three months later the baby died. Sullivan quit Vittoria and returned to York to seek the support of his family once more.

Upon his return, he again entered the law offices of W. W. Baldwin and Son, and later, in 1831, he established a partnership with Robert, who had married his sister. The firm, with such talented young lawyers, was soon prospering. On his birthday in 1833, the obviously bright and sensitive Sullivan reported to his brother Henry, then studying medicine in Ireland, that things were going well: “Augustus [another brother] . . . is now a Student of the Learned Society of Osgoode Hall – we have six clerks with plenty to do.” The partners were preparing “to go into parliament with the honorable body of Colonial Whigs. next election.” Sullivan and Baldwin had advanced their careers enough to consider themselves eligible to replace the recently dismissed attorney general, Henry John Boulton*, and solicitor general, Christopher Alexander Hagerman*. But, Sullivan said, because of’ their rumoured replacement by law officers from England, neither he nor Baldwin stood a good chance of getting “a silk gown.” By the end of 1833 Sullivan was once again thriving and on Boxing Day, in Stamford (Niagara Falls), Upper Canada, he married Emily Louisa, daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Chesneau Delatre.

His contemplations aside, Sullivan did not seek a seat in the election of 1834. The following year, however, he stood successfully as an alderman for St David’s Ward, Toronto, no doubt with the mayoralty in mind. A gentleman of Sullivan’s social standing and proven ability would have had little interest in aldermanic duties on a council just one year old. The mayoralty was another matter, however, as John Rolph’s actions the previous year had indicated. At the first meeting of council in 1835, Sullivan was confirmed mayor by tory and radical alike. As Toronto’s second mayor, he proved himself a competent administrator, approaching the problems of council from a practical rather than partisan perspective. Contested ward elections were the first problem; under Sullivan’s guidance, council adopted a set of regulations for hearing these grievances before proceeding with individual cases. Plagued with the same financial problems that had faced the first council [see William Lyon Mackenzie*], Sullivan turned his attention to amending the assessment laws. He was, as well, able to arrange financing for the city’s first major works project, a trunk sewer.

Public interest in municipal affairs was, however, sporadic at best. During 1835 council frequently could not convene for want of a quorum and there was discussion about compelling aldermen to attend. Sullivan’s last council meeting, lacking a quorum, was adjourned the following year and he declined to run again. There was, however, no lack of public interest in provincial politics, especially with the arrival of the new lieutenant governor, Sir Francis Bond Head*, in January 1836. And it was Sullivan, the erudite lawyer, who, as mayor of the provincial capital, delivered an address of welcome from the outgoing council.

The resignation on 12 March 1836 of Head’s Executive Council, of which Robert Baldwin had been a member, plunged the colony into its greatest political and constitutional crisis up to that point. With a haste that was indecent if nothing else, Sullivan accepted appointment to council and on the 14th was sworn in along with Augustus Warren Baldwin* (another uncle), John Elmsley*, and William Allan. Upper Canadian history provides other possible examples of political turncoats: Henry John Boulton deserved the epithet, John Willson probably did not. But Sullivan’s volte-face is without parallel. At the time of the reform brouhaha in 1828 over the dismissal of Judge John Walpole Willis*, Sullivan had declared, “It was against my principles to shew any respect to the present judges,” and, like his cousin, refused to plead before the “Pretended” Court of King’s Bench. A few years later he professed his eagerness to join the “Colonial Whigs” in the House of Assembly, without warning, he bedded down in 1836 with a group denounced by William Warren Baldwin as the “Tory junto.”

Sullivan has, unfortunately, left no explanation, or even rationalization, of his flip-flop. Reward was not long in coming: on 13 July he accepted the commissionership of crown lands, a plum worth £1,000 per annum. The patriarch of the Baldwin–Sullivan family was scathing. “R.S.,” W. W. Baldwin wrote to his son Robert, “is in the midst of enemies but he has thrown himself into their arms, & when they shake him over the precepice, he will not have a friend to console him.” A pariah among acquaintances and an object of rebuke by the whig press, Sullivan was isolated, almost. Robert Baldwin reminded his irate father that “family love” was “heavens best gift . . . let us not let political differences interfere with the cultivation of it – but on the contrary where such unhappily exist always forget the politician in the relation.” Despite Baldwin’s support for Sullivan, their legal partnership appears to have ended some time between 1836 and 1838.

Lord Durham [Lambton*] later derided Head’s appointments as ciphers. Sullivan proved an administration man, but he was no one’s tool. And what cannot be questioned is his ability. Head defended his choice, describing Sullivan as well-educated, a leading lawyer, and “a man of very superior talents . . . and of irreproachable character.” He quickly became the dominant figure in an increasingly active council. In a memorandum on the councillors prepared by Head, probably for his successor, Sir George Arthur, Sullivan was lauded as possessing “great legal talent [and] sound judgement particularly on financial questions,” whereas Allan, although honest and honourable, had “not much talent or education” and Elmsley was a “wrong headed man but brave.” Arthur relied heavily on forceful men with incisive analytical minds, such as Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson, John Macaulay, and Sullivan. In June 1838 Sullivan assumed the additional office of surveyor general. During Robinson’s long absence in England from 1838 to 1840, Arthur tended to ignore his law officers and other councillors in preference to Sullivan, who “takes a more enlarged view of the subjects, or, at all events, his sentiments fall more in with my motives of dealing with political questions in the present day; and, therefore, I have generally conferred with him in his office as presiding member of the Executive Council.” In February 1839 Sullivan was appointed to the Legislative Council. So crucial was he to the business of council and to the lieutenant governor as a policy adviser, that Arthur appointed Kenneth Cameron to serve as surveyor general pro tem, between October 1840 and February 1841, so that more important business need not be neglected by Sullivan.

In 1838, in the aftermath of the rebellion, Arthur had relied on him increasingly. That year Sullivan prepared, for instance, a mammoth report on the state of the province. The degree to which his analysis fell in line with that of his old enemies can be measured by Robinson’s enthusiastic approval. The report was “natural & forcible” and its tone “liberally conservative.” Sullivan took for granted that without natural or cultural barriers separating Upper Canada from the United States, the colony “must be materially affected by the state of Politics and of the popular mind in the neighbouring republic.” He uttered, albeit eloquently, the usual bromides that depicted American political culture in terms of “tyranny of a majority” and mob rule. He repeated, in short, current tory denunciations of responsible government and an elective legislative council as mere half-way houses to full-blown democratic institutions and chaos. In a manner worthy of Robinson at his best, he defended the Constitutional Act of 1791, the integrity of office holders, and the absolute need, if not the right, of an executive claim to revenues independent of control by the assembly.

Sullivan’s foray, in the same report, into policies on immigration, finance, and land matters marked his point of departure from tory nostrums. To his mind, tranquillity was a corollary of prosperity, which could only be achieved through large-scale immigration, a rise in the value of land, and productive public works. These measures would make people much happier “than any abstract political measures” could, and would have the effect of restoring public confidence and the colony’s trade. An enormous public debt sucked up available revenues and was responsible for leaving the province a largely inaccessible wilderness. The lack of superintendence of crown land produced a decline in revenue and immigration. Upper Canada, Sullivan maintained, must gain control of its major source of revenue, customs duties raised at Montreal and Quebec. To this end he gave full voice to a favourite tory war cry – annex Montreal, Trois-Rivières, and the Eastern Townships to Upper Canada, thus leaving the French Canadians to enjoy their own “bad laws, bad roads bad sleighs, bad food . . . in peace and quietness injuring no others and not being interfered with themselves.” The resurrection of union as a panacea for the Upper Canadian crisis would therefore be dangerous, since it would bring together and make supreme the democratic elements in Upper and Lower Canada. Over a year later, in 1839, Sullivan reiterated his hostility to union and his attachment to British institutions in a memorandum sent under Arthur’s name to the Colonial Office. He was at pains to distinguish two elements among the “conservatives”: those “who are so from principle, or attachment from sentiment to British institutions,” and the “Commercial party” which supported “prosperity, public credit and public improvements” but was conservative out of self-interest and only in prosperous times.

Sullivan’s lucid analysis of the province’s problems was matched by his equally deft set of practical prescriptions. He favoured the centralization of power, having urged Arthur in April 1838 to retain the power of patronage over the militia and not relinquish it to local colonels. That same year he recommended suspending work on the St Lawrence canals, lest the work become a “perpetual monument of Legislative folly & extravagance,” and he cautioned Arthur to rein in the commissioners responsible for the work. Although he supported the legitimacy of the constitutional privileges of the Church of England, the clergy reserves issue had to be settled in the interests of internal harmony. To this end he favoured dividing the reserves among the Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Wesleyan Methodists, with the proceeds from the reserves used “to secure religious instruction according to the protestant faith.”

In 1839 Arthur directed the Executive Council to prepare a report on how best to adapt land policy to the anticipated increase in immigration. The council split. Minority reports were submitted in 1840 by Sullivan and Augustus Warren Baldwin on one side, and William Allan and Richard Alexander Tucker* on the other. In fact, the reports were the efforts of Sullivan and Allan. Sullivan’s represents an eloquent and closely reasoned defence of an agrarian society, composed largely of independent farmers, as the basis for social and political stability and economic prosperity. Allan argued that the province’s economic backwardness could only be overcome by capitalist undertakings. Possessed of a shrewd, intuitive grasp of Upper Canada’s situation and its potential, Allan urged seizing the opportunity to establish “what we have been taught to consider a great desideratum, viz, a class of labourers, separate and distinct from Land owners.” Although Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson* (later Lord Sydenham) noted agreement with Allan’s position “as applied to a country under ordinary circumstances,” he saw the province’s present situation as different and he dismissed Allan’s opinion as biased and his arguments as “trashy in the extreme.”

Thomson, the architect of union, soon realized how useful Sullivan could be. He abandoned his previous hostility to union, a position which, as Attorney General Hagerman found out, Thomson would not tolerate. Sullivan was prominent in shepherding the measure through the Legislative Council, and appeared a solid “Governor’s man” at its inception. He was one of the four executive councillors, along with William Henry Draper*, Charles Richard Ogden*, and Charles Dewey Day*, in whom Robert Baldwin expressed want of confidence in February 1841. Sullivan retained the commissionership of crown lands until June of that year, in which month he was appointed to the new Legislative Council.

John Charles Dent*’s description of Sullivan, as a brilliant orator who charmed with his “Irish provincial accent” but who lacked conviction and steadiness of purpose, is accurate. He seems to have dozed through his duties as president of the Executive Council in 1841–42. He performed another wonderful turnaround in September 1842. When the new governor, Sir Charles Bagot*, was struggling to avoid a reform-dominated ministry, Sullivan supported him in the Legislative Council, asking, “Are we to carry on the government fairly and upon liberal principles or by dint of miserable majorities?” Yet he happily remained as president of council when the miserable majority prevailed, holding that position until November 1843 .

Indeed, he rapidly became a partisan of the new order, presumably an indication of his love of intrigue, his respect for power, and his weakness for flamboyant oratory. In October 1842 he was involved in the obdurate politics of the newly formed ministry of Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*, chairing the committee of the Executive Council which recommended withdrawing government advertising from newspapers “found to join in active opposition to the Government.” Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, Bagot’s successor in March 1843, was relatively complimentary to Sullivan as a minister, given that Metcalfe thought most of the executive councillors were fanatics, villains, or incompetents. According to his biographer, John William Kaye, the governor saw Sullivan as talented but dismissed him as inconsistent and lacking the “weight of personal character.” If a lightweight, Sullivan was prominent enough to be a target of the Orange order. After passage of the Party Processions and Secret Societies bills, there was a huge, furious Orange demonstration in Toronto on 8 Nov. 1843. Sullivan’s name was joined with those of the “traitors Baldwin and [Francis Hincks*]” on the mob’s banners.

During the ten-month crisis which followed the resignation of the Baldwin–La Fontaine ministry in November, Sullivan was in his element. His talents as an orator and pamphleteer gave him a prominent role in the reform campaign to justify the actions of the late ministry and win the election of 1844. His excessive zeal, however, at times injured the reform cause. He took part in the early meetings of the party’s new provincial organization, the Reform Association of Canada. At its first public meeting, in Toronto on 25 March 1844, Sullivan – ironically, given his “miserable majorities” speech – moved the resolution insisting that provincial ministries required the support of parliamentary majorities. He campaigned in 4th York with Baldwin and advised him on tactics. In September Baldwin reported consulting with Sullivan, James Edward Small*, and John Henry Dunn about whether to resign his militia commission and relinquish his appointment as queen’s counsel, in protest against Metcalfe’s autocracy. On their advice Baldwin retained his militia commission.

Sullivan’s most important role continued to be that of public controversialist. In May 1844 Egerton Ryerson* had begun a series of newspaper articles which supported the governor, and later published them as a pamphlet. He claimed to have been sympathetic to the councillors until their “real motives” were revealed by Sullivan and Francis Hincks, when he came to see Metcalfe as “a misrepresented and injured man.” Under the transparent nom de plume of Legion, Sullivan answered in 13 letters in the Examiner and the Globe. The letters, which also appeared as a pamphlet, contained no new insights but were an effective summary of the Baldwinite arguments for responsible government and provided a puncturing lampoon of Ryerson’s pomposity. They show, at places, Sullivan’s tendency to get carried away with his rhetoric. Later in the year the tories made good use of his indiscretion at an election meeting in Sharon, where, in ridiculing the governor as “Charles the Simple,” he seriously overstepped even the limits of that day. His excesses, however, were only one small factor in the reform defeat in the election of 1844. Sullivan ascribed it in large measure to the influence of the Orange order. “Ireland in its worst time,” he told Baldwin in January 1845, “was not more completely under the feet of an orange ascendancy than is Canada at present.”

With the party in opposition, Sullivan was not very active in the Legislative Council. He continued to be a close adviser to Baldwin on political matters, presumably more because of Baldwin’s stout family loyalty than because of his chequered record as a political tactician. He had a good deal to say about the worst crisis facing the party between 1845 and 1847: the tories’ wooing of French Canadians disenchanted with the reformers after the 1844 defeat. William Henry Draper came close to forging an alliance with René-Édouard Caron* and others in 1845–46. To Sullivan, writing to Baldwin in August 1846, Caron was “a false sneaking knave”; Hincks, who toadied to the French to maintain support, was nearly as bad. This outburst suggested that Sullivan had a conveniently short memory. La Fontaine did not. During the Draper–Caron flirtation, La Fontaine reminded Baldwin that Sullivan had made a similar attempt, in July 1842, to split the French from the reform party. He had approached both La Fontaine and Caron to enter the Bagot-Draper ministry and leave Baldwin behind.

There were issues on which the cousins differed. During the winter of 1844–45 Sullivan, who joined William Hume Blake* in a campaign to reform the Upper Canadian judicial system, expressed his deep disappointment that Baldwin would not give leadership on that effort in the assembly. More significant was their disagreement over tariff policy. After Britain’s adoption of free trade, Baldwin urged Canada, in a speech in November 1846, to follow that lead. Sullivan, however, was an early advocate of a different approach. Speaking to the Hamilton Mechanics’ Institute on 17 Nov. 1847, he championed the emerging capitalist interests of Canada, in sharp contrast to his position in 1840. Rapid industrial development was the solution to Canada’s economic problems, and he suggested the adoption of protective duties as a means to foster the needed industry. Published the following year, Sullivan’s Hamilton appeal was frequently cited when the protectionist movement began to gain strength after 1849.

Despite his political success in the 1840s Sullivan’s heavy drinking and fecklessness in business matters nearly destroyed his career. In 1843 he lamented his difficulty in collecting accounts, suggesting that his hand was all too often limp. In this he stood in marked contrast to his cousin. Baldwin was especially fierce in pursuing payment from the wealthy, who, he believed, had a moral duty to meet their debts. In 1844, however, things looked up. Oliver Mowat*, then a gossipy young lawyer, reported that Sullivan had joined the “total abstinence society.” It was a necessary step, in Mowat’s view, for no one in Toronto’s legal community had confidence in the drunken Sullivan. The reformation did not last. In the spring of 1848 Baldwin’s property manager, Lawrence Heyden, told Baldwin that Sullivan was in serious difficulty: “It is very generally reported here that he is broken out again.”

Dry or wet, Sullivan remained an intimate adviser to the party chief. His views were sought on delicate matters, such as the manœuvres in 1847 to find a seat for the recent convert from high toryism, Henry John Boulton, who remained anathema to many local reformers. When the party swept the election of January 1848, Baldwin suggested to La Fontaine 24 names, including Sullivan’s, as possibilities for the 11 cabinet positions. According to Baldwin, Sullivan preferred a judgeship, but his experience would be useful in cabinet. Presumably La Fontaine was not as generous about the missteps of Baldwin’s errant cousin, for Sullivan’s name did not appear on the cabinet list presented to Governor Lord Elgin [Bruce*] on 7 March 1848. La Fontaine and Baldwin told him they needed the seat to conciliate a faction in the party. On Elgin’s urging, however, they reconsidered and the next day Sullivan was included as provincial secretary, becoming the most senior of the ministers in terms of service. The governor was delighted for he considered Sullivan both able and “more British” than any other Canadian politician. In July he described Sullivan to Colonial Secretary Lord Grey as the member of council “who has the strongest feeling in favor of settling the lands of the Province and has most influence with his colleagues on questions of this nature.” Sullivan, for example, favoured free land grants and the construction of colonization roads – programs for these would be initiated in the 1850s.

Sullivan nevertheless played no major role in the “Great Ministry” and on 15 Sept. 1848, after resigning from council, he received his desired reward, a puisne justiceship on the Court of Queen’s Bench. He did not, however, entirely give up a political interest. While in cabinet, in April 1848, he had dismissed the medical superintendent of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, Walter Telfer, and replaced him with the apparently more politically sound George Hamilton Park. Park proceeded to feud with the staff and to fire employees without authorization. Sullivan followed the case closely and gave his assessment of it to Baldwin in January 1849; Park was dismissed that month and the radical newspaper, the Examiner, took his side against the “tyrannous” government. Sullivan guessed correctly that Park’s brother-in-law, John Rolph, was behind the crisis and warned Baldwin that the case was being used by such dissident reformers to embarrass the ministry.

Sullivan held his seat on the Legislative Council until May 1851. In January 1850 he had moved from Queen’s Bench to the newly formed Court of Common Pleas, where he sat until his death three years later. A superb orator and incisive analyst when sober, Sullivan nevertheless remained known as a flawed figure, devoid, in the opinion of Dent and others, of “genuine earnestness of purpose” and “strong political convictions.”

Victor Loring Russell, Robert Lochiel Fraser, and Michael S. Cross

Robert Baldwin Sullivan is the author of three pamphlets: Address on emigration and colonization, delivered in the Mechanics’ Institute Hall (Toronto, 1847); Lecture, delivered before the Mechanics’ Institute, of Hamilton, on Wednesday evening, November 17, 1847, on the connection between the agriculture and manufactures of Canada (Hamilton, [Ont.], 1848); and, under the pseudonym Legion, Letters on responsible government (Toronto, 1844).

AO, MS 78, John Macaulay to Helen Macaulay, 29 Nov. 1843; MU 2106, 1833, no.8; RG 22, ser.155, will of R. B. Sullivan. BNQ, Dép. des mss, mss-101, Coll. La Fontaine (copies in PAC, MG 24, B14). MTL, Robert Baldwin papers; W. W. Baldwin papers, B105, Robert Baldwin to W. W. Baldwin, 24 Sept. 1836; B136, Committee for the protection of the provincial press, 8 Nov. 1828; unbound misc., R. B. Sullivan to W. W. Baldwin, n.d.; Toronto papers. PAC, MG 24, B11, 9–10 (access restricted); B24, Robert Baldwin to G. H. Park, 31 March 1847; RG 1, E1, 45: 465–66; 52; 365. Arthur papers (Sanderson). Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1849, app.M, app.GGG. Elgin–Grey papers (Doughty). J. W. Kaye, The life and correspondence of Charles, Lord Metcalfe (new and rev. ed., 2v., London, 1858), 2: 339. Oliver Mowat, “‘Neither radical nor tory nor whig’: letters by Oliver Mowat to John Mowat, 1843–1846,” ed. Peter Neary, OH, 71 (1979): 84–131. Examiner (Toronto), 27 March 1844. Globe, 18 June–16 July 1844. Pilot (Montreal), 14 June 1844. N. F. Davin, The Irishman in Canada (London and Toronto, 1877), 410. J. C. Dent, The last forty years: Canada since the union of 1841 (2v., Toronto, [1881]). J. C. Hamilton, Osgoode Hall, reminiscences of the bench and bar (Toronto, 1904), 179. Edward Porritt, Sixty years of protection in Canada, 1846–1907, where industry leans on the politician (London, 1908). V. L. Russell, Mayors of Toronto (1v. to date, Erin, Ont., 1982– ). C. B. Sissons, Egerton Ryerson: his life and letters (2v., Toronto, 1937–47).

Cite This Article

Victor Loring Russell, Robert Lochiel Fraser, and Michael S. Cross, “SULLIVAN, ROBERT BALDWIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sullivan_robert_baldwin_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sullivan_robert_baldwin_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Victor Loring Russell, Robert Lochiel Fraser, and Michael S. Cross |

| Title of Article: | SULLIVAN, ROBERT BALDWIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 16, 2025 |