Source: Link

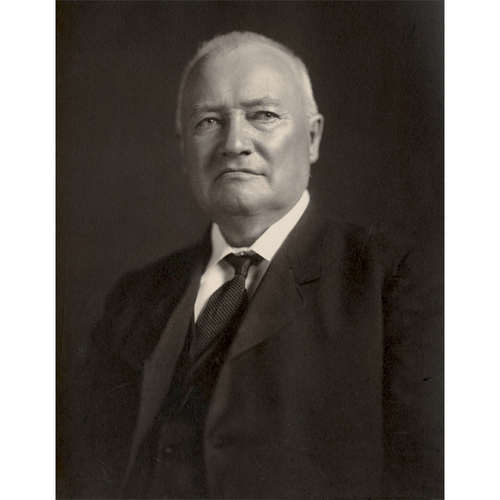

TACHÉ, EUGÈNE-ÉTIENNE, surveyor, civil engineer, civil servant, and architect; b. 25 Oct. 1836 in Saint-Thomas parish (at Montmagny), Lower Canada, son of Étienne-Paschal Taché*, a future premier of the Province of Canada and Father of Confederation, and Sophie Baucher, dit Morency; m. first 18 July 1859 Éléonore Bender (d. 1878) at Quebec; m. there secondly 22 Oct. 1879 Clara Juchereau Duchesnay; of his 12 children, 3 from his second marriage outlived him; d. 13 March 1912 at Quebec.

Born into the French Canadian middle class, Eugène-Étienne Taché attended primary school in Saint-Thomas and then the Petit Séminaire de Québec in 1846–47. Since his father was a cabinet minister and legislative councillor, he had to move when the seat of government changed. Thus Taché studied successively in Montreal, in Toronto, where he was enrolled at Upper Canada College in 1849, and from 1852 to 1855 once more at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he completed the first year of the Philosophy program. He then began a three-year course in surveying at the Department of Public Works under the direction of architect and surveyor Frederick Preston Rubidge*. Supervised by civil engineer Walter Shanly*, he was employed for 18 months doing soundings for the route of a canal projected to link Montreal with Lake Huron via the Ottawa River. On 10 Jan. 1859 he was appointed surveyor for Upper Canada. The following year he finished his apprenticeship at Quebec with engineer and architect Charles Baillairgé*, one of whose clients was Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché.

Taché became a licensed surveyor on 14 Oct. 1861. He was hired that year as a draftsman and surveyor with the Department of Crown Lands, but he resided in Ottawa only during 1866. After confederation, on 20 Sept. 1869 he would become assistant commissioner (deputy minister) of crown lands for the province of Quebec and would hold that office for the rest of his life, serving under 13 different ministers.

Beyond his work as a surveyor and cartographer, Taché was passionately fond of culture, art, and history. He was an ardent francophile, perhaps partly as a result of the active patriotism of his father and his cousin Joseph-Charles Taché*. On discovering that he was related to Louis Jolliet*, he had developed a keen interest in the history of New France, a history which the province of Quebec in the second half of the 19th century was busy recalling. He loved art most of all. A few lessons from painter Théophile Hamel* in 1862–63 had led him to illustrate “Forestiers et voyageurs; étude de mœurs,” a piece written by his cousin Joseph-Charles and published in Les Soirées canadiennes (Québec) in 1863. It was displayed at the universal exposition in Paris in 1867. Taché’s 14 drawings earned him high praise in Canadian newspapers.

It was only natural that, like Hamel before him, Taché should in 1867 make the pilgrimage to Europe that was then an integral part of North American culture. On his return, once he had freed himself from financial worries thanks to his salary as assistant commissioner, he embarked on a parallel career as an architect and artist, armed with the technical knowledge of his profession, to be sure, but above all trained in design concepts, interested in problems of composition, and stimulated by the romantic historicism gripping the European world he had discovered.

As an amateur, Taché was shut out from the community of North American architects. Instead of taking the practical training by which professionals of his day were educated, he had acquired his architectural knowledge through the books he bought and the journals, mostly French, to which he subscribed. Although he was totally removed from the emerging American modernism and the eclecticism characterizing the work of his contemporaries in the United States, Taché would nevertheless leave an indelible and highly personal mark on Quebec. Through his involvement in designing the city’s main public buildings, he would create the image of the new capital.

In the second half of the 19th century, as a result of archaeological and historical discoveries, a monolithic style had been succeeded by a catalogue of models from which artists could henceforth make an informed choice of the expressions and symbols being sought. In 1874, for instance, in response to an invitation from Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], architect William Henry Lynn suggested replacing the outdated fortifications of Quebec City by a new surrounding wall complete with medieval turrets, watchtowers, and square crenellations, whose picturesqueness would evoke a romantic memory of ancient fortifications.

Lord Dufferin tabled the plan for beautifying Quebec in 1874. The celebration of history was much in vogue, and this desire for commemoration earned Taché his first commission that year. A confirmed, even devout Roman Catholic, he received an order for nine temporary triumphal arches, to be set up in the city’s streets for the bicentenary of the diocese of Quebec. The artist-architect’s “delicately framed” drawings, which were still on public exhibit four years later, showed his ability. While supposedly presenting a chronicle of Christianity, the triumphal arches in their various styles – “Catacombs,” “Latin,” “Byzantine,” “Roman,” or “Gothic” – had suddenly introduced the complete history of architecture into the streets of Quebec. Taché had given conclusive proof of his expertise in historical expression. As a result, barely a month after the arches had been erected, Taché was commissioned by the Conservative government of Charles Boucher de Boucherville (of whom he was a well-known supporter) to draw up plans for the principal edifice in the capital, the legislative building.

For Taché, what mattered was to develop an aesthetic, a style that would be significant from the standpoint of the intended use of the building. Other local architects, including François-Xavier Berlinguet and Charles Baillairgé, would submit proposals, but they would be rejected. In comparison with the archaic neoclassicism of their plans, which revealed the stagnation of architectural circles at Quebec, the plans Taché presented in 1875 drew their inspiration from the French aesthetic, in the height of fashion since the famous enlargement of the Louvre, which was the cradle of Second Empire architecture and which he had visited in Paris. The artistic ethos of the legislative building also stood in contrast to the plan for the fortifications, which, though allegedly restoring a memory of New France, belonged mainly to the picturesque idiom of Great Britain. Above all, Taché’s stylistic aim was distinct from American eclecticism, which drew on the catalogued designs of contemporary architecture. Rather than take his inspiration from the addition to the Louvre, where 16th-century ornamentation had been interpreted in the search for a typically French style, Taché adopted its architects’ approach but chose as his reference point a monument from the French Renaissance, the Old Louvre. The language of Quebec’s principal building, constructed from 1877 to 1886, was clear. Rooted in the same past as that of the national style of France, it set down with a modern vocabulary the first stone of the province’s stylistic identity and legitimized the French origins of the emerging “nation.”

In this structure, more subdued and severe than the eclectic compositions of American architects would have been, Taché undertook to consolidate his historical aim in an iconographic program of a scope never before seen at Quebec. Combining historical painting, statuary, and carved coats of arms, the architect, with the assistance of artist Napoléon Bourassa, composed a pantheon of Canadian history, in a fountain “dedicated to the native peoples of North America,” in the statues of James Wolfe*, Paul de Chomedey* de Maisonneuve, and other figures, and in the tableaux of scenes, some of which were recreated from François-Xavier Garneau*’s Histoire du Canada. . . .

Taché would promote the first large commemorative monuments at Quebec, including that of Samuel de Champlain* (1898). Bent on embellishing the capital and its legislative building, he immersed himself in the study of heraldry. His hope was to provide his contemporaries with coats of arms bequeathing a memory, and at the same time to re-create Canada’s past through the heraldic devices of historical figures, which if he did not discover he invented. For the front wing of the legislative building, a new national emblem was officially approved on 9 Feb. 1883. It consisted of the province’s coat of arms emblazoned with an eloquent motto Taché had devised: Je me souviens.

To this motto, Ernest Gagnon wished to add another that the architect had coined: “Born among the lilies, I grew up among the roses.” It was in this spirit that Taché’s intense focus on symbols reached its zenith in February 1883 – before the legislative building had been completed – when he submitted the plans for the new Quebec court-house. Here he seemed to find the ideal relationship between historical commemoration and the creation of a “Quebec” architecture. Between the coats of arms of Champlain and Jacques Cartier*, devised for the occasion, which adorn the façade, the architect designed a true “Quebec order,” like the French and American ones already established in the lineage of the classical Greek and Roman orders. It combined the fleur-de-lis of France, the rose of England, and the maple leaf of Canada. A nation’s history was henceforth writ large on the walls of the modern capital.

Taché’s court-house did not, of course, conform to the rather British model of Canadian court-houses, which had been codified in Ottawa. Instead of the conventional aesthetic that a “professional” architect would have adopted, Taché had naturally maintained a stylistic continuity between the capital’s second building and the legislature. He opted, however, for an anterior reference, closer to the early-16th-century castles of the Loire than to the Old Louvre and thus more in keeping with the period of the discoverers, Cartier and Champlain, which the court-house’s historically convincing façade commemorated as if they had been present when it was erected.

Even before the end of 1883, Taché had given Quebec a new symbol of its coming of age in a third building, the Drill Hall. Here he kept the heraldic iconography and the symbolism of the fleur-de-lis and maple leaves, but for his models he went back to the medieval castles, earlier than the French classicism that had inspired the legislative building and the court-house. Pushing the origins of the city even farther back, in a sense, this late–15th-century idiom would inspire Taché’s draft plan of 1890 for the “Fortress Hotel,” which two years later would be a guide to architect Bruce Price* in designing the Château Frontenac. The coats of arms that decorate this building bear his unmistakable imprint.

Although it had a considerable effect on the architectural history of Quebec City and indeed of the province, Taché’s career as an architect was brief. After 1890 he did not carry out any more projects on the scale of his previous ones. He nevertheless gained a reputation for erudition. For example, he changed his repertory when drawing up the plans for the monastery of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary at Quebec (1895), when choosing for the porter’s lodge at Spencer Wood in Sillery (1890) the picturesque vocabulary appropriate to its wooded surroundings, and when designing a “trophy patterned after one of the gates of the Quebec citadel” for the province’s pavilion at an exhibition in Jamaica (1891). This pavilion, which was covered with cedar shingles supposedly representing Canadian practice – long before the shingle style made its appearance – was put up by Philippe Vallière.

Taché’s workload for the government may have helped shorten his architectural career. It should be noted, however, that the cost of constructing the legislative building had soared to a million dollars – five times the original estimate – by the day it was completed in 1886. This cost overrun certainly did not help the architect’s reputation in a period when speed of execution and technical modernity were becoming uppermost in people’s minds. When Liberal Lomer Gouin* became premier in March 1905, he owed little to this “old Bleu,” as Taché was called. He was 68 years of age by then. His design for a legislative library, which he had submitted in 1900, was finally turned down. In 1917 the government would opt for a building designed by architects Georges-Émile Tanguay* and Jean-Omer Marchand*, both well-known Liberals.

Taché was a 19th-century savant who showed little interest in architectonics. He worked diligently to produce hundreds of plans, many of them in colour, for ornamental details, and even hired draftsmen to perfect them. But he left the spatial layout, mechanical operation, and construction techniques in the hands of public works engineers and architects. For example, although he was certainly qualified to do it himself, he worked in partnership with Jean-Baptiste Derome of the Department of Public Works to plan and erect the legislative building. As for the courthouse, the press noted that Taché designed “the façades.”

In this respect Taché the architect and artist stood apart from the engineer, builder, or expert. He contributed only the bare essentials to the man-made landscape. This aesthetic interest was partly responsible for his obsolescence at the dawn of the 20th century, when it turned out the historicist had little to offer budding rationalist Americanism. Taché’s work, however, left an indelible mark on the urban scene, as he hoped it would. In 1906 he was appointed to the committee for beautifying Quebec in preparation for the 1908 celebrations. He would also design the tricentennial commemorative medal. As far back as 1880 he had conceived the idea of a great historical pathway encircling the city, which would open the way for developing the Parc des Champs-de-Bataille. Taché, who had witnessed prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s embellishments to Paris, viewed the city as a single vast entity in which buildings, set into a network by a coherent aesthetic and logic, all became monuments. Not surprisingly, everything he designed during his career as an architect was located along a single line, the Grande Allée.

Taché was remembered by his contemporaries as a modest man whose professional conscientiousness and diligence were proverbial. The journalist Hector Fabre* wrote in 1903: “He has never been seen out of his office during working hours, and hardly ever outside working hours . . . whenever you meet him, he is rushing to get to his office.” The man who had crowned the legislative building with an allegory entitled Religion et patrie, and who had coined the tinsmiths’ motto, “My innocence is my fortress,” for Saint-Jean-Baptiste day in 1880, was a monarchist, a francophile, and a sincere Roman Catholic, admired by most of his contemporaries. One of the titles conferred on him was companion of the Imperial Service Order (1903). He was the dean of the civil servants when, in November 1911, he was honoured with great pomp and ceremony on completing 50 years in the government’s employ. He died four months later, on 13 March 1912. An impressive funeral was held in the basilica of Notre Dame at Quebec, and the city continued long afterward to mourn the death of one of its “greatest figures,” an “exemplary patriot,” and a “man of genius.”

This “perfect civil servant,” a devoted employee of the state who had worked with Siméon Le Sage* and Pamphile Le May, had given his contemporaries the many fruits of a genuine talent; amongst his achievements were four maps of the province, which were “models of exactitude and clarity” according to Pierre-Georges Roy*. One of them, published in 1870, had earned him a bronze medal at the universal exposition in Paris in 1878. Taché’s chief claim to fame at Quebec is that he bequeathed a culture. As a case in point, he recommended that Louis-Philippe Hébert, the sculptor for the legislative building, go to Paris for lengthy training. There is no doubt, also, that painter Charles Huot* learned from Taché the fundamentals of his art while working on this building. And although Taché never claimed the title of architect, he made an unprecedented graphic contribution to a great many building plans and interior treatments (his total output contains, among other things, the plans for a number of religious buildings for various congregations) which are no doubt to be found here and there throughout the city, but without his signature.

Historical writing has taken little cognizance of Taché’s inventiveness or his modernity. In his search for a national style, he had, like the French, established a true state architectural agency, by encouraging the hiring of a number of architects. By repeating into the 1920s a formula divested of the creativity of its originator’s historical vision, these architects distorted Taché’s approach to modernism. They took a step backward from it, which was inevitably a step downward by comparison with the new modernist trends.

The spread of French influence in the second half of the 19th century helped Eugène-Étienne Taché to grace the memory of French Canada with a history, through heraldry and architectural expression. Even though his work did not win him fame as a creator, it was considered “a lesson and an example for his race,” as Le Soleil observed the day after his death. The provincial capital at the beginning of the 20th century was indebted to Taché for a large part of its French image, as it was for the historical richness it still displays.

More thorough treatments of Eugène-Étienne Taché and his architectural career appear in [Luc Noppen et Gaston Deschênes], L’Hôtel du Parlement, témoin de notre histoire (Quebec, 1986), and especially in the more detailed 1985 manuscript in Luc Noppen’s possession on which the published version is based; in Émilie de Thonel d’Orgeix, “Eugène-Étienne Taché, architecte (1836–1912): l’influence française à Québec, durant la seconde moitié du dix-neuvième siècle” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Toulouse Le Mirail, France, 1989); and in Francine Hudon, “L’architecte de l’Hôtel du Parlement de Québec: Eugène-Étienne Taché (1836–1912),” Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée Nationale du Québec, Bull. (Québec), 9, nos.3–4 (1979): 40–50.

ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 18 juill. 1859, 22 oct. 1879; CE2-7, 26 oct. 1836; CN1-112, 18 janv. 1853; E9, corr. générale, 1891, no.2003; P-286. ASQ, Fichier des anciens. Musée du Québec (Québec), Fonds Gérard-Morisset, dossier Eugène Taché. NA, Cartographic and Audio-Visual Arch. Div., NMC-17844. Private arch., Marie Boisvert (Québec), Letter from Taché’s heirs to the Quebec government, 1913. Quebec Land Surveyors Assoc. (Quebec), List of land surveyors. L’Action sociale (Québec), 13 mars 1912. Le Canada (Montréal), 14 mars 1912. Le Canadien, 18 janv. 1867. L’Éclaireur (Québec), 21 mars 1912. L’Événement, 13, 16 mars 1912. Le Journal de Québec, 17 janv. 1878. Montreal Herald, 25 April 1891. Le Soleil, 13–14, 16, 18 mars 1912. Christina Cameron, Charles Baillairgé, architect & engineer (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1989), 174. Canadian biog. dict., 2: 73–75. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), 2: 376. George Dickson, A history of Upper Canada College, 1829–1892 (Toronto, 1893), 301. Ernest Gagnon, Le fort et le château Saint-Louis (Québec); étude archéologique et historique (2e éd., Montréal, 1908), 162. La peinture au Québec, 1820–1850; nouveaux regards, nouvelles perspectives, sous la direction de Mario Béland (Quebec, 1991), 307. Qué., Parl., Doc. de la session, 1869–70, rapports du commissaire des Terres de la couronne, 1867–70. The roll of pupils of Upper Canada College, Toronto, January, 1830, to June, 1916, ed. A. H. Young (Kingston, 1917), 578. P.-G. Roy, La famille Taché (Lévis, Qué., 1904).

Cite This Article

Lucie K. Morisset and Luc Noppen, “TACHÉ, EUGÈNE-ÉTIENNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tache_eugene_etienne_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tache_eugene_etienne_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lucie K. Morisset and Luc Noppen |

| Title of Article: | TACHÉ, EUGÈNE-ÉTIENNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |