Source: Link

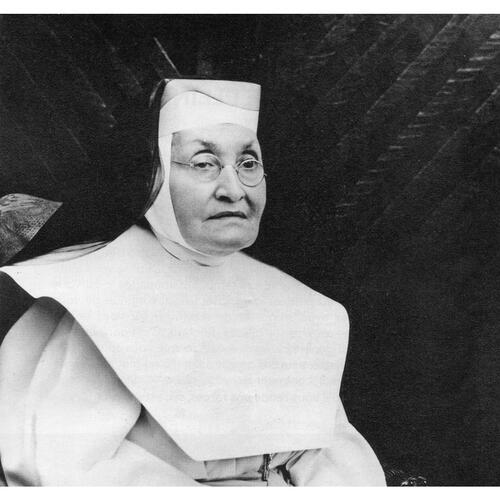

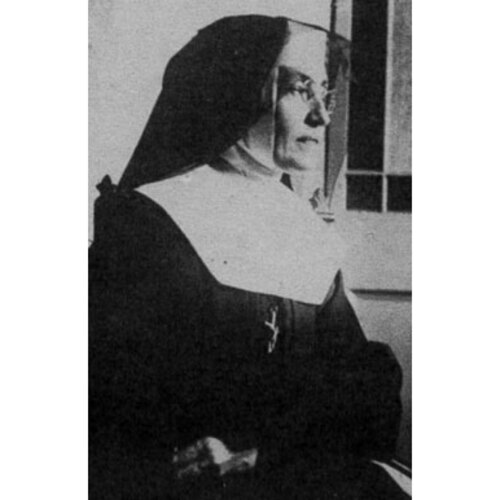

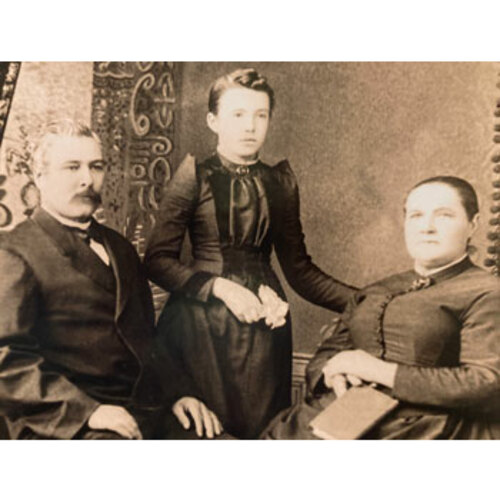

TÉTREAULT, DÉLIA (baptized Délia Tétreau), known as Marie du Saint-Esprit, foundress and first superior general of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception; b. 4 Feb. 1865 in Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir (Marieville), Que., daughter of Alexis Tétreau, a farmer, and Célina Ponton; d. 1 Oct. 1941 in Montreal.

Childhood, education, and religious calling

Like many children of her time, Délia Tétreault lost her mother very early, a few months before she turned three. When her father decided to try his luck in the United States, leaving with two or three of her elder siblings, she was entrusted to her godfather, Jean Alix, and his wife, Julie Ponton; thereafter she considered them her parents. A shopkeeper and sexton, Jean Alix had a very respectable social and economic standing in Marieville.

Délia Tétreault was educated at the Marieville boarding school, which was run by the Sisters of the Presentation of Mary. In an unfinished letter written in 1922 to the apostolic administrator of the archdiocese of Montreal, Bishop Georges Gauthier*, she would relate how, as an adolescent, she had hesitated between pursuing a secular life or her religious calling: “Those early years, which should have been the happiest of my life, were hardly so, torn apart as I was by the world, which attracted me on one side, and grace which urged me from the other.” In this story of her search for a vocation, she also explained that visiting bishops from the Canadian northwest, such as Vital-Justin Grandin*, had left a strong impression on her, as had the missionary accounts she had read in the annals of the Œuvre de la Sainte-Enfance and the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. Despite these experiences, in 1882 she asked to be admitted to the Carmelites, a contemplative order. She was not accepted, probably because of her delicate health.

The long quest for a vocation

In 1883 Tétreault presented herself to the Sœurs de la Charité de Saint-Hyacinthe, an order dedicated to service. She was admitted as a postulant on 15 October but left the convent in mid December because a fever epidemic had broken out. Once back at home, where she would remain for just over seven years, she looked after Julie, who was ill, and taught catechism to some of the parish’s children.

In her spare time Délia Tétreault enjoyed listening to sermons given by itinerant preachers. It was at one such gathering, in 1889, that she met the Jesuit priest Almire Pichon of France. He had been in the country for some time and the retreats he organized were well attended. She soon found him to be a good listener. After attending a May 1890 retreat with the Religious of the Sacred Heart at Sault-au-Récollet (Montreal), she realized that teaching communities held no appeal for her. In any case, Father Pichon had an entirely different idea in mind for his protégée. He was planning to establish a foundation to aid the very poor, and he wanted her to join in his efforts. Since his undertaking was not backed by his superiors or the archbishop of Montreal, Édouard-Charles Fabre*, he insisted that it remain secret. In June 1891 Tétreault joined Béthanie, the name of the centre that Father Pichon had inaugurated in April. For nearly ten years she taught catechism and looked after the sick and immigrants in need. Despite the usefulness of her work, the young woman was not sure she had found her calling.

This realization struck her even more forcefully when she befriended Father Alphonse-Marie Daignault, a Jesuit missionary who had returned from Africa. Their first meeting, sometime between 1891 and 1893, immediately reawakened her eagerness to support missionary endeavours. Her regular conversations with the Jesuit priest, whom she considered a trusted counsellor, gradually led her to form a new plan. Familiar with missions and their needs, he advised and guided her. Tétreault no longer saw her time at Béthanie as an end in itself, but as a period during which she could develop her missionary project, train for the stringent demands of the apostolate, and, above all, start to build a real network of contacts.

Among her fortuitous encounters was a meeting with Abbé Gustave Bourassa, brother of Henri* and almoner at the monastery of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd (Angers) [see Marie-Elmire Cadotte*] on Rue Sherbrooke. Now back in Africa, Father Daignault suggested that Tétreault seek Father Bourassa’s guidance. She did so early in 1900 and left Béthanie that autumn. She told him of the project that she and Daignault had dreamed of: opening an apostolic school to train young girls to work with the congregations that had overseas missions. After visiting such a school in Armagh, Ireland, Father Bourassa lent his support to the initiative, the only one of its kind in Canada. Paul Bruchési*, archbishop of Montreal, was rather hesitant, fearing that it would prove a financial burden on the archdiocese. But he finally let himself be persuaded and gave his approval on 12 Jan. 1901.

In April Tétreault went to Montreal’s Pensionnat Mont-Sainte-Marie, run by the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, to train for religious life. She stayed for a few months and formed a lasting friendship with Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie [Marie-Aveline Bengle*], who was then the mother superior’s assistant. On 3 June 1902 Tétreault and two companions, Joséphine Montmarquet and Ida Lafricain, moved to the Côte-des-Neiges municipality (Montreal) and prepared to open the apostolic school. Célina Montmarquet, Josephine’s sister, ensured the institution’s early financial survival: having a small inheritance from her parents, Célina took up residence in the house as a boarder. Tétreault could also count on Abbé Bourassa, the school’s spiritual father and a material benefactor. Owing to his generosity, the following year the group was able to settle in a larger building on Chemin de la Côte-Sainte-Catherine in Outremont (Montreal). In this new space the school’s staff managed to finance the training of recruits by making liturgical ornaments and vestments for the recently established parish of Saint-Viateur-d’Outremont and by opening two classes for the neighbourhood’s children.

The founding of a unique community

Two years after opening, the school had only five aspirants to the religious life. Tétreault wondered whether she should carry on despite the discouraging results or instead set up a traditional missionary congregation. While she was agonizing over her institution’s future, she lost her principal supporter: Abbé Bourassa died on 20 Nov. 1904. Moved by his premature death, Archbishop Bruchési agreed, ten days later, to submit the school’s case to Pope Pius X. In an address given on 8 Aug. 1905, the archbishop would report that the pontiff had immediately replied, “Found it, Your Grace, and all celestial blessings will descend upon this new institution.” The pope’s decision meant that, at a stroke, the project Tétreault had initiated became a religious institution devoted to overseas missions under the name Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception. It was the first Canadian religious community to adopt such a mandate.

Tétreault and her companions had heard the news on the evening of 16 Dec. 1904. However, they had to await Bruchési’s return to Montreal in early spring to work out certain details, such as their habit (it would be black, modelled on that of the Congregation of Notre-Dame) and the date of the first ceremony when vows would be made. Still counselled by Daignault, Tétreault developed a rule of community life and wrote a preliminary version of the constitution, entitled “Draft.” The sole purpose of the new religious community, she wrote, lay in the evangelization of non-Christian peoples, and “at [the] slightest indication … the Society must be ready to send its subjects to the most deadly climates, under the most difficult and perilous conditions.” She spoke in a similar vein about the spiritual power that must animate the members of her missionary congregation and emphasized the need for gratitude: “To God first, our thanksgiving should be incessant.” She returned to this idea with even more conviction in a letter addressed to Sister Marie-Immaculée in 1916: “The more Our Lord makes me penetrate into the spirit of our vocation, the more it seems to me that the principal raison d’être of our Society is really thanksgiving.”

On 8 Aug. 1905 Archbishop Bruchési presided over the ceremony during which Tétreault made perpetual vows, under the name Marie du Saint-Esprit, and thus became the de facto superior general of the new institution. Joséphine Montmarquet also committed herself, taking temporary vows and the name Marie de Saint-Gustave. Three other companions were in the first group of novices. Financially, the fledgling community could always rely on the support of Célina Montmarquet. The small classes begun under the organization’s auspices in 1903 continued, as did the apostolic school itself. In 1905 Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit also established an association of laywomen called the Dames patronnesses. These extremely energetic women organized tombolas, outdoor events, and other activities to help the community fulfil its obligations. Early in 1908 a sewing circle was started to benefit missions.

First mission

Next arose the question of where to establish the first outpost. In Rome, Cardinal Girolamo Maria Gotti, prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide) and head of the mission territories, imposed no restrictions on the Missionary Sisters. On 7 Nov. 1908 Bruchési wrote to Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit: “All mission countries are open to you. The bishop who wishes to have you will have only to contact me and then notify the Propaganda Fide.” In the letter he also announced that the apostolic prefect of Canton, China, Bishop Jean-Marie Mérel, would be happy to receive them. The community’s first mission was thus chosen: six nuns embarked for China on 8 Sept. 1909.

Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit’s duties increased with this expedition. The sisters had barely arrived before they were sending numerous requests to their superior for nuns to respond to the demands of the work and for money to purchase basic necessities, which were all too often lacking. To obtain more recruits and more consistent financial support, the foundress had to make her community known and arouse missionary fervour in her own country. She devoted herself unceasingly to the task – to the detriment, wrote some sisters who had been sent abroad, of the missionary work itself. For Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit, however, everything was connected. By promoting the Missionary Sisters and developing missionary zeal in Canada, she ensured that she had the resources and the personnel needed to bring her apostolic endeavours to fruition in other countries.

Recruiting and promoting

Forty-eight new congregations for women were established or founded in Quebec between 1901 and 1940, bringing the total to 88. They all sought recruits and financing. Faced with such competition, Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit had to be strategic. The Montreal newspapers had widely publicized the 1909 departure of the first missionaries for China, and the foundress had no intention of letting her fledgling community fall into oblivion. The inauguration of closed retreat houses throughout the province and the opening of regional institutions for postulants and apostolic schools from 1911 onwards were intended to foster vocations. Accounts and photographs from missions also turned out to be remarkable promotional tools. Starting in 1926, the superior general would even send the young women she supervised into Quebec schools and parishes with magic lanterns to enliven their talks with displays of photographs on glass plates.

The community’s involvement in promoting pontifical mission societies such as the Œuvre de la Sainte-Enfance and the Society for the Propagation of the Faith provided a unique opportunity: while the Missionary Sisters were raising funds for their congregation and overseas missions, they were also spreading the word about their existence to the largest possible number of people by visiting Quebec families and schools. The sisters took part in radio broadcasts and numerous missionary exhibitions. Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit’s most valuable asset, however, remained Le Précurseur. The community newsletter was first delivered from the Outremont mother house in May 1920, and an English edition appeared in September 1923. Publishing four issues a year initially, and then six, demanded a considerable investment of the sisters’ time and energy: besides writing and printing, they went door to door selling subscriptions. Circulation grew from 10,000 copies in 1925 to 55,000 in 1940.

Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit’s gamble paid off. The community’s numbers rose from 70 in 1920 to 485 in 1940. The increase was enough for the Missionary Sisters to open up new apostolate fields in the Philippines (1921), Japan (1926), Hong Kong (1927), and Manchuria (People’s Republic of China) (1927), for a total of 19 active missions in 1940. Similarly, Canadian initiatives with Chinese immigrants flourished in Montreal, Quebec City, and Vancouver. Wherever they found themselves – orphanages, hospices, schools, boarding schools, hospitals, community clinics, and leper-houses – the daughters of Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit did not flinch from any challenge. They also provided religious instruction and trained catechists. The Missionary Sisters owed much to the foundress’s remarkable communication skills. Even if her promotional strategies and tools were not necessarily new or unique, Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit used them to the best advantage. Although she could not take all the credit for her congregation’s successes, it was really thanks to her multi-faceted vision of the missionary apostolate that the community benefited from its prominence.

Institute of pontifical right

On 1 March 1925 Rome finally approved the constitutions Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit had submitted five years earlier. The Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception thereby became an institute of pontifical right, answering directly to Rome instead of to diocesan authorities. The community abandoned its black attire and adopted a white habit, retaining the blue belt added in 1909 in honour of the Virgin. At this time, without the foundress’s knowledge, the community’s general council obtained a special privilege from Pope Pius XI that would allow her to remain the superior general unless the privilege was revoked by the Holy See.

Société des Missions Étrangères

Délia Tétreault had often discussed with Father Daignault a second missionary project: an apostolic school for boys. Over time she instead came to favour the creation of a seminary to train missionary priests. For years she worked to convince Quebec’s bishops of the merit of her idea. During the summer of 1920, Archbishop Bruchési exhorted her: “If you want a Canadian seminary, find me some priests!” The first turned out to be Abbé Louis-Adelmar Lapierre. Exhausted by a long walk one day, he appeared at the Missionary Sisters’ mother house and asked for a cup of coffee. Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit came downstairs to meet and chat with him. Nothing more was needed to convince her that she had finally found her earliest recruit.

From then on things moved quickly. In October 1920 bishops and clergymen gathered at the mother house to discuss setting up a seminary for those who intended to work in overseas missions. On 2 Feb. 1921 the province’s assembled bishops decreed the founding of the Séminaire de la Société des Missions Étrangères de la Province de Québec [see Guillaume Forbes*; Joseph-Avila Roch*]. Although she was not its official foundress, Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit could certainly claim to have a nurturing role in the new mission institution. Even if she did not intervene in any way in the society’s internal affairs, she continued to take an interest in it as the years passed. She suggested to members of lay associations, among others, that they work to support it, and decorations for the chapel, bedding, linens, and various forms of handiwork were thus offered to the society’s superiors in January 1924.

Last years and assessment

On 28 Sept. 1933 Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit had a stroke. Her health improved gradually, but there were serious lasting effects: she remained semi-paralysed and it was difficult for her to speak. Despite the care given by her congregation’s daughters, her strength steadily declined. Reluctantly, the community resolved to choose a new superior general who could provide leadership. In January 1939 Mother Marie de la Providence, who had been assistant general since 1921, assumed the role.

Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit died on 1 Oct. 1941. On the following day her body lay in state. Messages of condolence poured in from all over. On 6 October Archbishop of Montreal Joseph Charbonneau* conducted the funeral service in the mother house’s chapel, where a large assembly had gathered to pay tribute. The foundress’s remains were then taken to the community cemetery in Pont-Viau (Laval) and buried on 7 October. The cause for her canonization was presented on 19 May 1985, and on 18 Dec. 1997 John Paul II declared her venerable.

At a time when the missionary movement had scarcely begun to stir in Quebec, Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit founded the first Canadian religious community dedicated to overseas missions. Although she never set foot outside the province, for over 30 years she contributed to putting Canada at the forefront of missionary countries.

Thanks to her skilful communication strategies and promotional tools, Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit ensured the success, in the area of finances and personnel, of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception. The congregation maintained its momentum after its foundress’s death: in 1968, at its height, there were 991 nuns active in Canada and in 66 missions around the world.

Délia Tétreault left few documents that offer evidence of her life before the founding of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception: some personal notes; an unfinished letter written in 1922 to Archbishop Paul Bruchési that describes the history of her call to the religious life; rare confidences about her childhood recorded by close colleagues; and the account that she gave to Canon Avila Roch after her stroke in 1933. There are also some 50 letters from people who had known her before her community was founded. She wrote no treatise on spirituality; however, she left an extensive correspondence of more than 2,000 letters. A selection was published in Délia Tétreault in her time: letters, trans. Brenda Rose et al. (3v., Outremont [Montreal], 1987–2010).

The most up-to-date information on Délia Tétreault can be found in the author’s Women without frontiers: a history of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, 1902–2007, trans. Kathe Roth (Outremont, 2008), and in Délia Tétreault, fondatrice de l'Institut des Sœurs missionnaires de l'Immaculée Conception (1865–1941) (2v., Rome, 1989–90), the historical biography written for her cause for beatification. Reprints of all documents cited in this biography are included in the latter.

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin Coll.), 1621–1968”, Saint-Christophe (Laval, Québec), 7 oct. 1941: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 15 May 2024). Arch. des Sœurs Missionnaires de l’Immaculée-Conception (Laval, Québec). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE602-S21, 5 févr. 1865. J.-F. Alabré, Vie d’action de grâces et mission selon Délia Tétreault, sous la dir. de Benoît Lacroix (Montréal, 2000). Georgette Barrette, Délia Tétreault and the Canadian Church (Outremont, 1989). Micheline D’Allaire, Vingt ans de crise chez les religieuses du Québec, 1960–1980 ([Montréal], 1983). Marta Danylewycz, Taking the veil: an alternative to marriage, motherhood, spinsterhood in Quebec, 1840–1920, ed. P.-A. Linteau et al. (Toronto, 1987). Hélène De Serres, Délia Tétreault and the Virgin Mary (Montreal, 1986). Éléments pour une sociologie des communautés religieuses au Québec, Bernard Denault et Benoît Lévesque, édit. (Sherbrooke, Québec, et Montréal, 1975). Éliette Gagnon, Délia Tétreault and thanksgiving (Outremont, 1989). Albertine Graton, [dite sœur Saint-Jean-François Régis], “Le cycle d’or: histoire de la congrégation des Sœurs missionnaires de l’Immaculée-Conception, 1902–1952” (typescript, 1952–55); Les trente premières années de l’Institut des Sœurs missionnaires de l’Immaculée-Conception, 1902–1932 ([Montréal], 1962). Histoire du catholicisme québécois, sous la dir. de Nive Voisine (2 tomes en 4v. parus, Montréal, 1984– ), tome 3, v.1 (Jean Hamelin et Nicole Gagnon, Le XXe siècle (1898–1940), 1984). Guy Laperrière, Les congrégations religieuses: de la France au Québec, 1880–1914 (3v., Sainte-Foy [Québec], 1996–2005). Nicole Laurin et al., À la recherche d’un monde oublié: les communautés religieuses de femmes au Québec de 1900 à 1970 ([Montréal], 1991). Pauline Longtin, Fondement de l'esprit missionnaire chez Délia Tétreault (Montréal, 1983). [A.-M. Magnan, dite sœur Sainte-Marie-Madeleine], Mère Marie du Saint-Esprit (Montréal, [1960?]). Sister Marie du Saint-Esprit [Délia Tétreault], Listening to Délia, comp. Gisèle Villemure, trans. Antoinette Kinlough (Montreal, 1997). Yves Raguin, Au-delà de son rêve: Délia Tétreault ([Saint-Laurent [Montréal]], 1991). Gisèle Villemure, Who is Délia Tétreault?: Mother Marie du Saint-Esprit, 1865–1941, trans. Madeleine Delorme and Edita Telan ([Montreal, 1983]).

Cite This Article

Chantal Gauthier, “TÉTREAULT, DÉLIA (baptized Délia Tétreau), known as Marie du Saint-Esprit,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tetreault_delia_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tetreault_delia_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Chantal Gauthier |

| Title of Article: | TÉTREAULT, DÉLIA (baptized Délia Tétreau), known as Marie du Saint-Esprit |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |