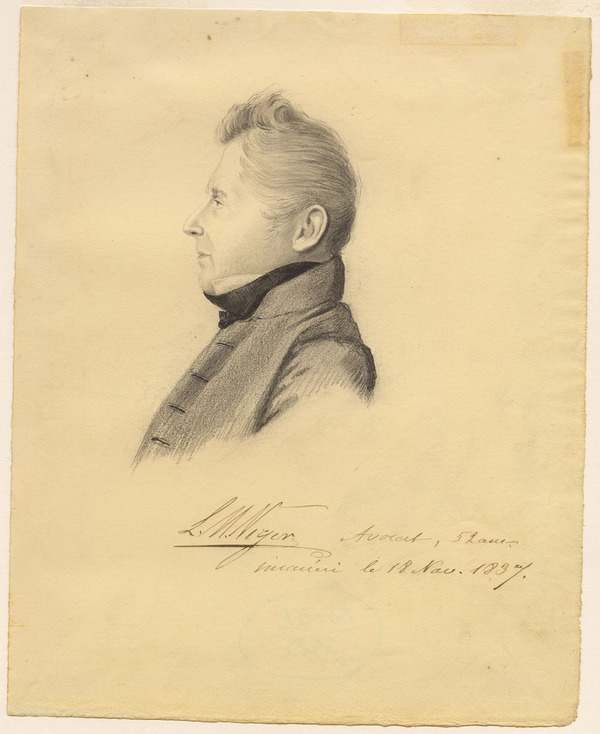

VIGER, LOUIS-MICHEL, lawyer, militia officer, landowner, politician, banker, Patriote, and seigneur; b. 28 Sept. 1785 in Montreal, son of Louis Viger and Marie-Agnès Papineau; d. 27 May 1855 in L’Assomption, Lower Canada, and was buried three days later in Repentigny.

The Vigers were an old family of craftsmen who soon after the conquest began a remarkable rise to prominence in French Canadian society. Louis Viger was living in Montreal and working as an blacksmith when the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763. Four years later he married Marie-Agnès Papineau, sister of Joseph Papineau* and later the aunt of the great Louis-Joseph*. This marriage played a part in building the network formed by the important Papineau, Viger, Cherrier, and Lartigue families.

Louis-Michel Viger was the seventh of nine children. By the time of his birth his father had apparently become an ironmaster, the sign of an appreciable improvement in his status. Hence Louis-Michel was given a classical education at the Collège Saint-Raphaël from 1796 to 1803. He studied there with his cousin Louis-Joseph Papineau, and the two boys quickly formed a brotherly friendship that endured for the rest of their lives. Before his studies were completed Viger had decided to become a lawyer, and in 1802 had started legal training under his cousin Denis-Benjamin Viger*. Called to the bar on 5 July 1807, at the age of 21, Louis-Michel began to practise in Montreal.

A brilliant young lawyer of distinguished bearing, Viger had useful family connections and so was received into the homes of the new and increasingly important petite bourgeoisie in his native city. He was so popular that he was tagged “le beau Viger.” Like many in the professions, Viger was exploring the ideas of liberty, equality, and sovereignty of the people, which were beginning to circulate in Lower Canada, and he was gaining a sense of his French Canadian nationality. Consequently, he soon became interested in politics. He may have joined the Canadian party in this period, probably at the same time as Louis-Joseph Papineau. Certainly, during the general election of 1810 precipitated by Governor Sir James Henry Craig* to deal with the political crisis in the colony, Viger declined to sign a congratulatory address to Craig endorsed by the senior officials and important British merchants; he also managed to dissuade a good many Montreal citizens from adding their signatures. In June of that year Thomas McCord* and Jean-Marie Mondelet*, justices of the peace in Montreal, accused Viger of being disloyal to the colonial authorities and trying to impede the English party’s candidates, but nothing came of the matter.

Like others of the French Canadian petite bourgeoisie, Viger had heeded the official call to arms issued by administrator Thomas Dunn* during the summer of 1807 to meet a threatened American invasion. In 1808 he had enrolled as an ensign in Montreal’s 2nd Militia Battalion. When the War of 1812 broke out he was made a lieutenant, and in 1814 a captain in the same battalion. During this period he also obtained a commission as lieutenant in the 5th Select Embodied Militia Battalion of Lower Canada. He served throughout the conflict, demonstrating his attachment to British institutions.

At the end of the war Viger resumed the practice of law. He soon became one of the best known lawyers of the Montreal bar and, through competence, diligence, and kindness, acquired a great many clients. In 1822 he took into partnership Côme-Séraphin Cherrier*, a cousin who had been called to the bar that year. On 19 July 1824, at Saint-Charles, near Quebec, Viger married Marie-Ermine Turgeon, a daughter of Legislative Councillor Louis Turgeon*, the seigneur of Beaumont, and niece of Pierre-Flavien Turgeon*, later archbishop of Quebec. The marriage was solemnized with great ceremony in the presence of numerous relatives and friends, including Viger’s cousins, Denis-Benjamin and Jacques Viger. Louis-Michel and his wife then went to live in the family residence on Rue Bonsecours in Montreal. Their four children were born in that house, which he apparently had inherited on the death of his father in 1812. In 1825 Viger also owned properties in the eastern part of the old town that earned him an annual income estimated at between £100 and £200.

While practising law, Viger had continued to involve himself in politics. He was one of a group of Montreal reformers who after 1815 steadily acquired influence within the Canadian party. During the 1820 election campaign he spoke at a meeting in support of Hugues Heney*, whom he helped to win a seat for Montreal East in the House of Assembly. Subsequently Viger began frequenting Édouard-Raymond Fabre’s bookstore on Rue Saint-Vincent, where he regularly met the reform leaders of the Montreal region. In 1827 he was relieved of his captaincy in Montreal’s 2nd Militia Battalion for having taken part in election meetings where resolutions were passed condemning the policy of Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*] concerning the civil list [see Denis-Benjamin Viger].

In 1830 Viger himself entered the political fray, probably at the urging of Papineau, who thought his cousin and best friend would be an excellent representative for his party. In the general election that year he was chosen with Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel* to represent Chambly. Once in harness at Quebec, Viger realized that public life was absorbing most of his time, and in 1832 he had to give up legal practice. In the house he proved a keen supporter of Papineau, and in particular voted for the 92 Resolutions. During the election campaign of 1834 he defended the Patriote party program with unflagging energy and had no difficulty winning in Chambly again, this time with Louis Lacoste*. Viger’s political convictions led him to take part subsequently in several patriotic demonstrations. For instance, he participated in the Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebrations in 1835. The following year he was amongst the first to contribute to the fund organized to compensate Ludger Duvernay, the publisher of La Minerve, who was serving a third term in jail for contempt of court.

In 1835 Viger had also decided to go into business. He joined a group of merchants closely associated with the Patriote party who, considering themselves disadvantaged by the Bank of Montreal’s stranglehold on credit in Lower Canada, proposed to set up a new bank which would provide the capital to foster small businesses and industries owned by French Canadians. Viger became the chief proponent of the plan, which to his credit he carried through successfully. In his colleague Jacob De Witt he found the man to help him organize and direct the new undertaking. The two formed Viger, De Witt et Cie, a limited partnership with an initial capital of £75,000 to which De Witt contributed heavily. This company, which was also known as the Banque du Peuple, had 12 principal partners, each of whom had to invest substantial capital and to assume responsibility for its operation. Papineau did not initially approve of the plan, and told Viger it would be “the tomb of your popularity and even your patriotism.” He none the less realized that the bank might constitute a powerful weapon in the struggle against the important minority of major British merchants in the colony, and he soon urged his compatriots to support it. Viger and De Witt in any case forged ahead with their venture, and under their skilful guidance the company was assured of success from its earliest years. The bank’s clients were chiefly farmers and artisans, who turned to it for loans.

When the British parliament in March 1837 adopted the resolutions of Lord John Russell, which proposed the removal of all assembly control over the executive, Viger strenuously opposed their application and committed himself to the Patriote movement. He was one of the members who supported the boycott of British products advocated by Papineau. Furthermore, along with such members as Édouard-Étienne Rodier* and De Witt, he appeared at the opening of the new session of the house in August dressed in homespun clothes. He took part in several of the gatherings held on the eve of the rebellion. On 4 June, with Lacoste and Timothée Kimber, he had attended a protest meeting in Chambly County. On 23 October at the Assemblée des Six Comtés at Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu, he took his place on the platform as a member of Papineau’s inner group and addressed the crowd immediately after his cousin.

In view of his part in various large pre-revolutionary meetings, Viger was recognized by the authorities as a leader of the Patriote movement. One of the 26 for whom a warrant of arrest was issued on 16 Nov. 1837, he was charged with high treason and thrown into prison two days later. As for the authorities’ objective, Ægidius Fauteux* suggests: “It was not impossible that in arresting him they hoped especially to ruin his banking establishment. The claim was made that the real purpose behind this institution was to give cash advances to the rebels’ army.” It was an easy matter for members of the English party to spread this rumour when the rebellion broke out on 23 November.

There is some question about the nature of the links between the Banque du Peuple and the rebel movement, and, according to historian Fernand Ouellet, nothing can be said with certainty on the matter. The only explicit proof that there was a connection is the testimony of Étienne Chartier, who denounced those at the head of the bank because at the eleventh hour they had refused to finance the insurrection. In Ouellet’s opinion there are various indications that the two were closely linked: the ties of kinship and friendship between Papineau and the bank’s directors and shareholders, the steady contact Viger maintained with Papineau until the Patriote leader left Montreal, Viger’s arrest, and the hasty visit that bank director Édouard-Raymond Fabre paid to Saint-Denis on the Richelieu where he met with Papineau and Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan* after Viger was jailed and just prior to the outbreak of fighting there.

Whatever the case, Viger’s lawyer, William Walker*, had to engage in a real legal battle to secure the release of his client. Around the middle of December 1837 Walker made his first request for a writ of habeas corpus, which was rejected because martial law had just been declared. On 13 March 1838 he failed to obtain Viger’s release because he had addressed his request to a sheriff who did not have the prisoner under his guard. On 21 April he again sought a writ of habeas corpus, this time from Lieutenant-Colonel George Augustus Wetherall*, but two days later the Special Council passed an ordinance suspending the use of habeas corpus in the colony until 24 August. Before it was reinstated, a general amnesty was decreed on 23 June 1838. Viger refused, however, to supply the security required and to give pledges of good conduct. Only in his fourth attempt, on 25 August, did Walker succeed in getting Viger set free, on bail of £2,000. Viger gave way then because most of the other prisoners had accepted the terms of the amnesty, and he had no desire to languish in prison. On 4 November, the day after the outbreak of the second rebellion, he was arrested again, but he was freed without trial on 13 December.

Viger had doubtless been exhausted by his two prolonged stays in prison, and was then severely tried by his wife’s death on 9 June 1839. Thus for a period he concentrated exclusively on his own affairs. However, he was to involve himself in public affairs once more when in February 1840, along with a good many French Canadian politicians of the Montreal region, in particular Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Denis-Benjamin Viger, he signed a petition denouncing the resolutions passed by the Special Council in Lower Canada and the House of Assembly in Upper Canada concerning the union of the two colonies. Their efforts proved vain. When the union was inaugurated in 1841, Viger was amongst those who called for its repeal. Standing in his old riding of Chambly in the general election that year, he was defeated by John Yule, the government candidate, after a campaign marred by irregularities and numerous acts of violence. In association with five other defeated reform candidates, among them La Fontaine, he presented a petition to have the election, which he termed fraudulent, declared null and void. The Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada found technical reasons for turning down the request. In 1842, at a by-election for the seat vacated by Augustin-Norbert Morin*, Viger was elected member for Nicolet.

Viger married again on 10 Sept. 1843 at L’Assomption; he took as his second wife Aurélie – the daughter of Joseph-Édouard Faribault, the widow of Charles Saint-Ours, and the seigneur of L’Assomption and of the Bayeul fief. They were to have no children. In this period the Banque du Peuple, which had survived the revolutionary upheaval, underwent considerable expansion, and Viger and De Witt were successful in seeking a charter by which it was incorporated in 1844 with a capital of £200,000. In 1845 Viger was appointed its president for life, and De Witt its vice-president. The following year Viger also agreed to join the honorary board of directors of the new Montreal City and District Savings Bank. By the time his term as member for Nicolet was up in 1844, he had decided not to stand at the next general election, and he retired for a few years with his wife to the manor-house of the seigneury of Saint-Ours in L’Assomption. He must already have amassed a sizeable fortune, for in 1848 he purchased the seigneury of Repentigny from Henry Ogden Andrews for £1,450.

Viger ran again, in the 1847–48 general election, and was elected member for Terrebonne. Papineau, whose interests during his exile had in part been looked after by Viger, also won a seat. When Robert Baldwin and La Fontaine were asked by Governor Lord Elgin [Bruce*] to form a new government, they approached Viger, who on 11 March accepted the office of receiver general with a seat on the Executive Council. But in so doing he incurred the censure of Papineau, who criticized him for approving of the régime he had sought to have repealed in 1841. As a former Patriote, Viger was one of the members who in March 1849 voted for the Rebellion Losses Bill. When the issue of annexation arose, along with the rest of the Executive Council he signed a declaration of loyalty published in La Minerve on 15 Oct. 1849 in reply to the Annexation Manifesto which had appeared four days earlier. After the Parliament Building in Montreal had burned down, the Executive Council moved to Toronto, which in November became the new capital of the province. That month Viger protested against this decision and resigned as receiver general, insisting that he was unable to “share the views of [his] colleagues on the matter of the seat of government.” He none the less continued to sit in the house as an ordinary member. In the general election of 1851 he was returned for Leinster, a seat he retained until 1854. He retired shortly afterwards to the manor-house of Saint-Ours in L’Assomption, where he died, apparently of a paralytic stroke, on 27 May 1855, at the age of 69.

The son of a skilled tradesman and entrepreneur, Louis-Michel Viger was a man who advanced to a markedly higher status, securing for himself an important place within the petite bourgeoisie of French Canada in the first half of the 19th century. He struggled ardently, first for the Patriote cause and then, after the rebellion and the union of the Canadas, for responsible government. A few days after his death, in a letter to Jean-Joseph Girouard dated 30 May 1855, Papineau expressed his grief at the loss of the man he considered his spiritual brother: “My friend and kinsman of the heart and of boyhood, with whom I grew up like a brother, Louis Viger, only one year older than I, is gone, and I learn this just as I write to you.” According to the provisions detailed in the inventory of his estate, which was drawn up on 17 Oct. 1855, Viger left to his second wife a handsome fortune, the seigneury of Repentigny, and a few properties in Montreal.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 19 janv. 1767, 28 sept. 1785; CE5-14, 10 sept. 1843; CE5-16, 30 mai 1855; CN1-194, 13 mai 1802; CN1-226, 7 déc. 1848; CN1-312, 17 oct., 28 nov. 1855; CN5-11, 10 sept. 1843; P1000-3-290. ANQ-Q, CE2-4, 19 juill. 1824; CN1-230, 19 juill. 1824; E17/6, no.44; E17/15, nos.921–25; E17/16, nos.926–61; E17/38, nos.3074–75; P-68; P-69. Arch. de l’Institut d’hist. de l’Amérique française (Montréal), Coll. Girouard, lettre de L.-J. Papineau à J.-J. Girouard, 30 mai 1855. ASQ, Fonds Viger–Verreau, Carton 46, no.9; Sér.O, 0139–40; 0144; 0147. BNQ, Dép. des mss, mss-101, Coll. La Fontaine (copies at PAC). BVM-G, Fonds Fauteux, notes compilées par Ægidius Fauteux sur les Patriotes de 1837–1838 dont les noms commencent par la lettre V, carton 10. PAC, MG 24, B2; B46; RG 4, B8, 18: 6501–4; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841; 1841–67. L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1830–37. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1842–44; 1848–54; Statutes, 1843, c.66. “État général des billets d’ordonnances . . . ,” Pierre Panet, compil., ANQ Rapport, 1924–25: 229–359. “Un document important du curé Étienne Chartier sur les rébellions de 1837–38: lettre du curé Chartier adressée à Louis-Joseph Papineau en novembre 1839, à St Albans, Vermont,” Richard Chabot, édit., Écrits de Canada français (Montréal), 39 (1974): 223–55. La Minerve, 17 déc. 1827; 12 juin, 26, 30 oct. 1837; 15 oct. 1849; 29 mai 1855; 28 juill. 1857. La Patrie, 5 juin 1855, 22 juill. 1857. Le Pays, 23 juill. 1857. Quebec Gazette, 13 March 1820. F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 295–96. Desjardins, Guide parl. Fauteux, Patriotes, 396–98. Lefebvre, Le Canada, l’Amérique, 350. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire, 2: 784. Montreal directory, 1842–55. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving). Quebec almanac, 1807–41. Terrill, Chronology of Montreal. Wallace, Macmillan dict. J.-G. Barthe, Souvenirs d’un demi-siècle ou Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire contemporaine (Montréal, 1885). Hector Berthelot, Montréal, le bon vieux temps, É.-Z. Massicotte, compil. (2v. in 1, 2nd ed., Montréal, 1924), 2: 28–29. Buchanan, Bench and bar of L.C. Campbell, Hist. of Scotch Presbyterian Church, 254–55. David, Les gerbes canadiennes, 175. Filteau, Hist. des Patriotes (1975). A.[-H.] Gosselin, Un bon Patriote d’autrefois, le docteur Labrie (3rd ed., Québec, 1907). R. S. Greenfield, “La Banque du peuple, 1835–1871, and its failure, 1895” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968). Clément Laurin, J.-J. Girouard & les Patriotes de 1837–38: portraits (Montréal, 1973), 112. Maurault, Le collège de Montréal (Dansereau; 1967). Monet, La première révolution tranquille. Ouellet, Bas-Canada; Éléments d’histoire sociale du Bas-Canada (Montréal, 1972); Histoire économique et sociale du Québec, 1760–1850: structures et conjoncture (Montréal et Paris, [1966]). C. Roy, Hist. de L’Assomption, 186, 206–7, 444. J.-L. Roy, Édouard-Raymond Fabre. P.-G. Roy, Toutes petites choses du Régime anglais, 1: 284–85; 2: 142–43. Robert Rumilly, Artisans du miracle canadien: Régime anglais (Montréal, 1936), 42–44; Histoire de Longueuil (Longueuil, Qué., 1974); Histoire de Montréal (5v., Montréal, 1970–74), 2; Papineau et son temps. T. T. Smyth, The first hundred years: history of the Montreal City and District Savings Bank, 1846–1946 (Montreal, [1946]). Tulchinsky, River barons. L.-P. Turcotte, Le Canada sous l’Union, 1841–1867 (2v., Québec, 1871–72). Mason Wade, Les canadiens-français de 1760 à nos jours, Adrien Venne et Francis Dufau-Labeyrie, trad. (2nd ed., 2v., Ottawa, 1966), 1: 189. J.-P. Wallot, Un Québec qui bougeait: trame socio-politique du Québec au tournant du XIXe siècle (Sillery, Qué., 1973). F.-J. Audet, “Le barreau et la révolte de 1837,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 31 (1937), sect.i: 85–96; “L’honorable Louis-Michel Viger,” BRH, 33 (1927): 354–55. Édouard Fabre Surveyer, “Les trois Viger,” BRH, 53 (1947): 29. Montarville de La Bruère, “Louis-Joseph Papineau, de Saint-Denis à Paris,” Cahiers des Dix, 5 (1940): 79–106. J.-J. Lefebvre, “Les députés de Chambly, 1792–1967,” BRH, 70 (1968): 3–19; “La famille Viger: le maire Jacques Viger (1858); ses parents – ses ascendants – ses alliés,” SGCF Mémoires, 17 (1966): 203–38. Henri Masson, “Louis-Michel Viger, député de Terrebonne, procureur général – prisonnier politique,” SGCF Mémoires, 18 (1967): 198–205. Louis Richard, “Jacob De Witt (1785–1859),” RHAF, 3 (1949–50): 537–55. “Une institution nationale: la Banque du peuple,” Rev. canadienne, 31 (1895): 82–97.

Cite This Article

Michel de Lorimier, “VIGER, LOUIS-MICHEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/viger_louis_michel_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/viger_louis_michel_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel de Lorimier |

| Title of Article: | VIGER, LOUIS-MICHEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | August 7, 2025 |