Source: Link

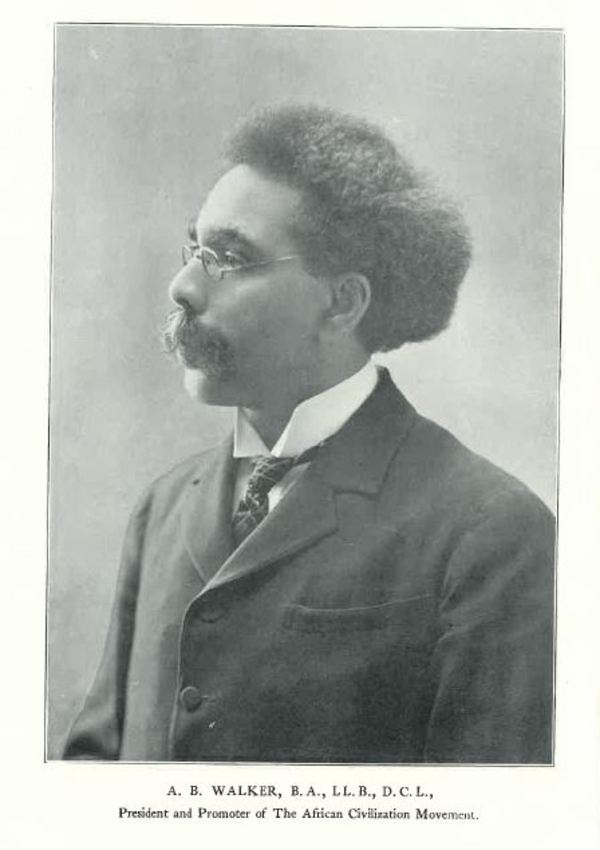

WALKER, ABRAHAM BEVERLEY, lawyer and journalist; b. 23 Aug. 1851 in Belleisle (Belleisle Creek), N.B., son of William Walker and Patience Taylor; m. 30 July 1876 Eliza Ruth Marsh in Saint John, N.B., and they had five children; d. there 21 April 1909.

A. B. Walker’s loyalist ancestor was among the first blacks to settle on the Kingston peninsula, upriver from Saint John, in 1786. The son of a farmer, Walker was probably educated in the school operated by William Elias Scovil, Anglican rector of Kingston, whose method of shorthand he may have learned. While still in his teens, Walker was employed as secretary and stenographer by the American phrenologists Orson Squire Fowler and Samuel Roberts Wells, who toured the Canadian provinces as part of their lecture circuit. After graduating from the National University in Washington, D.C., Walker returned to Saint John and commenced a three-year studentship in the office of lawyer George Godfrey Gilbert, supporting himself as a shorthand reporter. He graduated llb from the National University law school, and was admitted an attorney of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick in June 1881. He was called to the bar in June 1882, thus becoming the first native Afro-Canadian lawyer – a distinction hitherto wrongly conferred on Delos Rogest Davis* of Ontario. Towards the end of his life he would also claim to have earned a dcl, but no documentary evidence exists to support his assertion.

Walker opened a law office in Saint John, where blacks constituted a minuscule 1.2 per cent of the population, but his practice did not flourish. He became involved in the New Brunswick Shorthand Association, of which he would serve as vice-president in 1886, and was also active as a court reporter. In July 1885 he was an unsuccessful examinee for the post of official court stenographer. He also became distracted by the problem of racial prejudice: his conspicuous exclusion from the private banquet organized by a senior member of the Saint John Law Society in December 1885 to commemorate the centenary of the New Brunswick bar led to an embarrassing public controversy over the “color line.”

Walker’s professional prospects looked so bleak that by the end of 1889 he had decided to emigrate to the United States. Armed with testimonial letters from the justices of the Supreme Court, among others, he went to Atlanta, Ga; he had been informed “upon credible authority,” he told Lieutenant Governor Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*, that there the “outlook . . . for a lawyer of my race trained in the rigid discipline of British Courts and British Institutions generally is exceedingly hopeful and encouraging.” He lectured publicly on “the negro problem,” and made up his mind “to become a Georgian in all the moods and tenses of the term.” Within two years, however, he was back in Saint John, where his wife and family had remained throughout. In October 1892 he was the first student to matriculate at the newly organized Saint John Law School, then a faculty of King’s College in Windsor, N.S., and now the University of New Brunswick faculty of law. The following year, in June, he successfully applied to become librarian of the Saint John Law Society, an office he would hold until January 1899, when he was superseded for being absent without leave.

In 1895 the Afro-Canadian community of Saint John petitioned Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper*, minister of justice in the federal Conservative administration, for Walker’s appointment as qc. Although they were assured that his name would be brought forward, the undertaking was not honoured. Walker attributed his omission to racial discrimination. “As soon as it was rumoured that I was likely to be appointed,” he afterwards complained to Liberal prime minister Wilfrid Laurier*, “there was a fierce conspiracy at once got up here to prevent it, and the Ministry at Ottawa had not the courage and fairness to face it and do me justice and fair play.” Walker believed that he had been wronged by the Conservative leaders in New Brunswick, whom he had loyally supported since the federal election of 1878, when he organized the black electors of Saint John into a “political club” and delivered their votes en bloc to the party. In any case, the new Liberal minister of justice, Oliver Mowat, declined to interfere in the matter, and Walker never obtained his qc. Recognition came later in the form of an honorary doctorate, presumably conferred by his alma mater. In 1907, claiming to be “the senior Negro lawyer in the British Empire,” he asked Attorney General Harrison Andrew McKeown* for an appointment as a provincial kc, but he was again disappointed.

Throughout his career Walker was an indefatigable essayist, lecturer, and traveller. The apex of his journalism came in February 1903 with the launching of Neith, a monthly “magazine of literature, science, art, philosophy, jurisprudence, criticism, history, reform, economics.” Walker, as editor, vigorously solicited contributions not only from academics and literati, but also from leading political and professional men. Before 1904 was out, however, Neith had ceased publication because of inadequate financial support. According to Robin W. Winks, it had “introduced into Canadian journalism a magazine fully the equal of most monthly literary periodicals of the time and to Negro journalism as a whole a publication superior to most.”

After the collapse of Neith Walker threw himself into the founding and promotion of the African Civilization Movement, which had close links with the African Methodist Episcopal Church and of which he served as president. The chief object of the movement was to create in British Africa an exemplary colony of intelligent and industrious blacks drawn from Canada and other English-speaking countries. Walker travelled throughout Canada and the United States promulgating his ideas, but met with little success. He was touring Ontario on behalf of the movement when he was overtaken by the pulmonary tuberculosis which led to his death.

By the mid 1890s A. B. Walker viewed himself as the leading man of his race in the Maritimes, and there seems no good reason to dissent from Winks’s judgement of him as “clearly a man of exceptional intelligence, dedication, and energy.” Psychologically as well as ideologically a black supremacist, Walker argued for black rights on the basis not so much of racial superiority as of racial antiquity: he claimed the Afro-Canadian pedigree was ancient Egyptian. In doing so, he simply inverted white racist arguments for the separate and unequal treatment of black people. Walker’s concept of negroes as a superior race may well have been rooted in the pseudo-science of phrenology, which had influenced his primary intellectual formation. Unlike Booker T. Washington, a realist whose program he criticized in Neith, Walker was a utopian idealist. His impact on the progress of the Afro-Canadian community in New Brunswick as elsewhere in the Maritimes was therefore minimal. Walker’s having been the first native Afro-Canadian lawyer and, until James Robinson Johnston* was called to the bar in 1900, the only black barrister in the Maritimes has nevertheless assured him his place in history.

Abraham Beverley Walker is the author of The negro problem; or, the philosophy of race development; from a Canadian standpoint: a lecture (Atlanta, Ga, 1890; copy in N.B. Museum); “The trials, hardships and destiny of the negro race; an appeal to the tribunal of humanity for fair play and justice,” a series of articles in the Saint John Globe, Saturday supp., 20 Feb.–3 April 1897 (available on mfm. at the Saint John (N.B.) Regional Library); Victoria the good: the great and glorious mother of liberty, justice, right, truth and equity, of modern civilization; and the mightiest force for righteousness in the world since the time of Jesus: a lecture (Saint John, 1901; copy in N.B. Museum); “The negro problem and how to solve it,” an unfinished series published in his periodical, Neith (Saint John), no.1 (February 1903)-no.5 (January 1904); and A message to the public by Dr. A. B. Walker, president and promoter of the African Civilization Movement (Saint John, 1905; copy in Acadia Univ. Library, Wolfville, N.S.). A complete run of Neith is available in the W. F. Ganong papers at the N.B. Museum, as well as at the Saint John Regional Library.

NA, MG 26, G: 6207–14 (mfm. at PANS). N.B. Museum, Reg. of marriages for the city and county of Saint John, book I (1875–80): 173, no.202 (mfm. at Saint John Regional Library); Tilley family papers, box 11, folder 1, doc.24. PANB, MC 288, MS4, petition of A. B. Walker, 1881; MS7/H; RS9, 24 March 1908, A. B. Walker to H. A. McKeown, 2 Dec. 1907. Saint John Law Soc., Council records, minutes, 1893–99. Daily Sun (Saint John), 1882–87, continued as St. John Daily Sun, 1887–1906, and as Sun, 1906–9. Saint John Globe, 1882–1909. Standard (Saint John), 1886–1909. D. G. Bell, Legal education in New Brunswick: a history (Fredericton, 1992). W. A. Spray, The blacks in New Brunswick ([Fredericton], 1972). R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (Montreal, 1971), 292, 398–401, 411; “Negroes in the Maritimes: an introductory survey,” Dalhousie Rev., 48 (1968–69): 467–69.

Cite This Article

J. B. Cahill, “WALKER, ABRAHAM BEVERLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_abraham_beverley_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_abraham_beverley_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. B. Cahill |

| Title of Article: | WALKER, ABRAHAM BEVERLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |