Source: Link

WASHINGTON, THOMAS C., barber, restaurateur, boarding-house keeper, impresario, and music teacher; b. c. 1837 in New York City, son of John Washington and Eliza ———; m. c. 1860 Mary Elizabeth Watson (d. 1911) in Saint John, and they had five sons and three daughters; d. there 1 March 1897.

Thomas C. Washington frequented the Black grammar schools of New York City, where he received, according to the St. John Daily Sun, “a good common school education.” Eventually, he made his way to Saint John, arriving in 1860. The Black residents of New Brunswick formed a very small proportion of the population. Most were descendants of enslaved persons, indentured servants, or free Black people who had accompanied the loyalists to the area in 1783 [see Thomas Peters*] or were refugees from the War of 1812 [see Ward Chipman* (1754–1824)]. A few, such as Robert J. Patterson* and Robert W. Whetsel, the husband of Georgina Mingo*, had recently escaped the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in the United States.

Washington married in Saint John soon after his arrival. To support a growing family, he opened a barber shop. “Attentive and polite,” the Daily Sun would say, “he soon became popular, and consequently had a large patronage.” His establishment, situated in 1877 on Prince William Street, was lost in the devastating fire of that year [see Sylvester Zobieski Earle*]; his residence, at 236 Duke, may not have been spared either since in 1877–78 he lived for a time on Bridge Street in Indiantown (Saint John). Local reporting indicates that Washington benefited from the estate of his mother, who had died in 1875, leaving property in New Jersey said to be worth $50,000. This legacy may have helped the family get re-established after the fire: they acquired a home at 124 Mecklenburg Street, purchased for $3,000 from Cornelius Sparrow, a fellow Black businessman, and opened another shop at 32 Charlotte, opposite the city market.

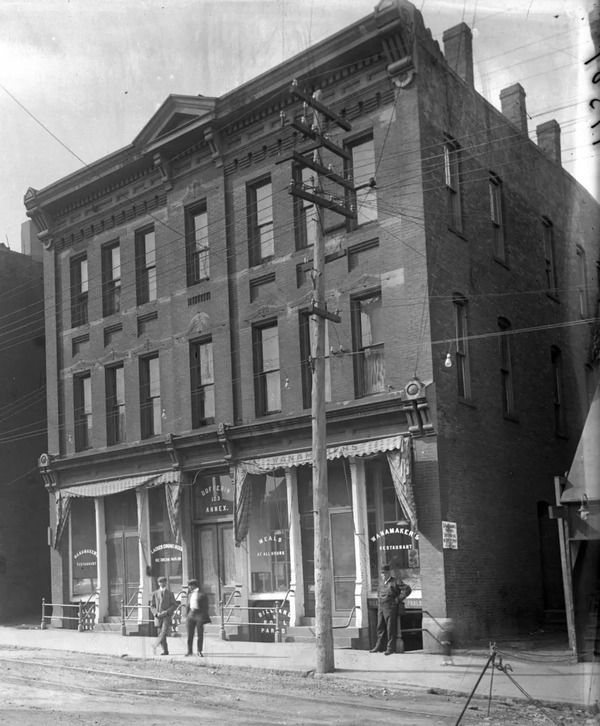

In 1880 Washington consolidated his enterprises by taking over the saloon and restaurant of George Sparrow, brother of Cornelius, at 103–5 Charlotte, strategically located across the street from the popular Dufferin House hotel. Wisely, he kept the operating name as the Lorne Restaurant, which was well known to the café’s clients. He also opened quarters for his hairdressing business in the new premises and used the upper storeys to take in boarders. The establishment became known as Prescott House.

Active in the community, Washington was a strong supporter of St Philip’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. He was also a member of several civic and fraternal groups, including the freemasons and the Seven Star Lodge of the Independent Order of Good Templars, a temperance organization. By 1880 he was the grand worthy councillor of the order’s Grand Lodge of New Brunswick. Along with the Sparrows and others, he founded two of the earliest Black temperance lodges in New Brunswick, which may also have been the first in Atlantic Canada. By 1890 he was a vice-president of the African Methodist Episcopal Church Temperance Society. Involved in the Oddfellows as well, in 1889 he had become the principal founder and noble grand of the all-Black Acadia Lodge. In October 1883, during the 100th-anniversary celebrations of the arrival of the loyalists in New Brunswick, he and other representatives of the Black community, including Robert Patterson and Abraham Beverley Walker*, had joined members of the New Brunswick Historical Society for an Arbor Day ceremony at Queen Square; the tree Washington planted was dedicated to the memory of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

While still in New York in the 1850s, Washington appears to have received some formal training in the arts, with an emphasis on dramatic and operatic performances. He and his wife gave support and direction to benefits held by others at the theatre in the Saint John Mechanics’ Institute, their participation being first mentioned in the local press in 1878. Washington was soon actively engaged in putting on shows himself. Advertisements that year referred to him as Professor Washington and mentioned what was apparently his earliest group of entertainers, the Jubilee Singers. Another of his companies was the Colored Juvenile Pinafore Troupe, which gave three performances in 1880.

Washington also had an orchestra, which in 1881 furnished the music for the annual ball of Intercolonial Railway officials in Moncton. By 1887 a concert group he had put together, the Colored Ideal Concert Company, was a regular attraction at the mechanics’ institute. In a review of a performance given on 8 February that year, the Daily Telegraph noted that the audience, who had braved inclement weather to attend, “found no reason to regret that they had left their homes.” Later the same year, Washington visited New York to secure additional performers. They were to participate in a course to be offered at the mechanics’ institute, a course that would be combined with concert performances in Saint John, Fredericton, and Halifax.

In May 1889 Washington put on a concert to benefit the Royal Ball Club. Evidence suggests that the club was subsequently called the Ralph Waldo Emerson Colored Baseball Club, after the American poet-philosopher and well-known abolitionist, but sports fans may have found the designation too cumbersome. In June 1890 the Fredericton Daily Gleaner reported that the Emerson captain challenged a team of local journalists to a game. Although the first organized baseball club in Saint John was formed in 1853, documentation for the first Black baseball teams dates to the late 1880s. At least two of Washington’s sons were among the players. Since many others were unable to afford uniforms or equipment, participation in local teams may have depended on benefits Washington gave in their support.

Throughout the 1890s Washington’s restaurant flourished and was often the scene of after-theatre suppers, which particularly attracted patrons of the Opera House on Union Street. When they were available, Buctouche oysters were offered at the bar. Beginning in 1891, the café operated a popular ice-cream parlour during the summer months. To meet the growing demand for the more than ten flavours he stocked, including pistachio and pineapple, Washington brought in electricity to help prepare the delicacy. Like many Saint John businesses, Washington’s was reliant on local ice deliveries [see Georgina Mingo].

To assist him and his wife at this time, Washington employed his sons Robert L. and Edward and his daughter Florence. Florence also participated actively in his theatrical troupes and in light-operatic productions in the city. While Thomas Washington dealt with the restaurant, expanding its services to include providing “pocket lunches” for visitors to such functions as the annual Saint John Exhibition, the other family members looked after the boarders in Prescott House.

In February 1897, at the peak of the family’s fortunes, Thomas C. Washington suffered an acute attack of Bright’s disease, which exacerbated, the Daily Sun reported, “a general breaking up of the system through overwork.” Within a week, on 1 March, he died at 60 years of age. In paying tribute to him, the Daily Telegraph on 2 March noted his successful business and civic life, and emphasized his devotion to “anything that tended to uplift the colored population of this city.” His wife, Mary, who lived until 1911, carried on the family business with Florence’s help, until it was sold in about 1905.

Daily Gleaner (Fredericton), 20 June 1890. Daily Telegraph (Saint John), 26 June 1877; 22 Oct. 1878; 24 Jan., 5 Feb. 1879; 22, 26 Nov. 1880; 27 Sept., 6 Oct. 1883; 8, 9 Feb., 26 Sept. 1887; 21 Sept. 1888; 4 Sept. 1889; 20 June 1890; 15, 21 April 1891; 21, 24 May, 23 Sept., 19 Dec. 1895; 2 March 1897. Daily Times (Moncton, N.B.), 23 Feb. 1881. St. John Daily Sun (Saint John), 2 March 1897. Telegraph-Journal (Saint John), 31 May 1955. Directory, N.B., 1865–68. Directory, Saint John, 1869–98. McMillan’s agricultural and nautical almanac … (Saint John), 1880, 1890. N.B. Hist. Soc., Loyalists’ centennial souvenir (Saint John, 1887).

Cite This Article

Roger P. Nason, “WASHINGTON, THOMAS C.,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/washington_thomas_c_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/washington_thomas_c_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roger P. Nason |

| Title of Article: | WASHINGTON, THOMAS C. |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |