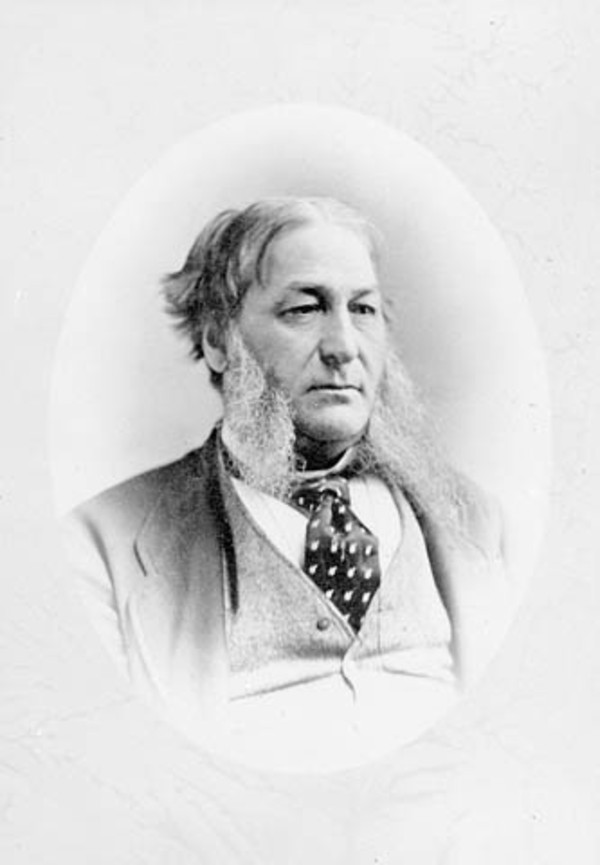

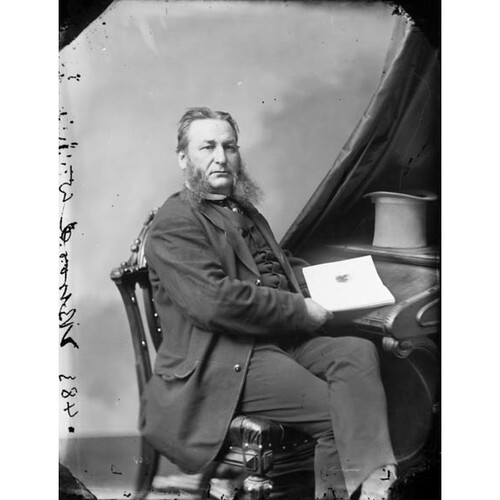

WOOD, EDMUND BURKE, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. probably 13 Feb. 1820 at or near Fort Erie, Upper Canada, the fourth son of Samuel and Charlotte Wood; m. in April 1855 Jane Augusta Marter of Brantford, Canada West; d. 7 Oct. 1882 at Winnipeg, Man.

Edmund Burke Wood was the son of an Irish-American farmer who had immigrated to the Niagara District shortly after the War of 1812. He was educated in local schools at Fort Erie and, after the loss of an arm had apparently ruled out remaining on the farm, became a teacher in Wentworth County. Wood found teaching both unrewarding and unpromising, however, and entered Oberlin College, Ohio, from which he graduated with a ba in 1848. The following year he enrolled as a student with the Law Society of Upper Canada, articling first with the firm of Samuel Black Freeman and Stephen James Jones in Hamilton, and later with Archibald Gilkison of Brantford. Through the influence of Jones, he was appointed clerk of the county court and deputy clerk of the crown in Brant County in 1853, thereby becoming widely known in local legal circles. He resigned both offices after being called to the bar in 1854 and subsequently established a profitable legal partnership in Brantford with Peter Ball Long. Industrious, thorough, and knowledgeable, Wood soon emerged as one of Brantford’s most prominent lawyers, and during his 20-year career in the county courts handled celebrated cases in criminal, common, and equity law. An abrasive and difficult colleague, he practised alone after the dissolution of his partnership in 1860.

Wood’s business and political careers were inextricably linked. In the mid 1850s he became the solicitor and one of the principal promoters of the Buffalo and Lake Huron Railway, a line which promised to open profitable trading opportunities for Brantford in New York State. In 1863, partially to extend his personal influence and partially to promote the railway, he first ran for public office, winning the West Brant seat in the Legislative Assembly as a moderate Reformer. After the Buffalo and Lake Huron line was taken over by the Grand Trunk Railway the following year, Wood came increasingly under the influence of Charles John Brydges of the Grand Trunk and his friends in the Conservative party. As Brydges wrote to John A. Macdonald* in 1864, Wood was “quite ready to take the shilling if you were in a position to offer it to him.” Although a nominal Liberal throughout his career, Wood disregarded George Brown*’s call to retreat from the “Great Coalition” in 1866, evidently because of Grand Trunk influence. To the disappointment of the supporters of Brown, in 1867 Wood accepted the office of treasurer of Ontario in John Sandfield Macdonald*’s “Patent Combination” coalition ministry. The leading Reformer in the Ontario cabinet, he was elected as a coalitionist to both the Ontario legislature and the House of Commons in 1867, despite his repudiation by the Liberal riding association in South Brant.

Wood remained treasurer of Ontario for more than four years despite frequent quarrels with Sandfield Macdonald and open disagreements with the federal wing of the coalition. Leading a group of ministerial mavericks at Ottawa he opposed the grant of “better terms” to Nova Scotia, and refused to support Sandfield’s defence of the federal government in 1869. As treasurer he zealously guarded the financial interests of Ontario. Echoing the sectionalist rhetoric of pre-confederation Reformers, he assumed a firm stance during the financial arbitration between Ontario and Quebec. He was equally influential in guarding his own interests. Once called “an active paid agent of the Grand Trunk” by the Toronto Globe, Wood, unlike most of his party, opposed the construction of narrow gauge railways in the province.

In 1871, following a provincial election which left control of the legislature in doubt and which demonstrated Wood’s inability to secure Liberal support for the coalition, he resigned his post dramatically as the “Patent Combination” struggled vainly for survival. After the ministry’s collapse, he rejoined the Liberal party and supported the new provincial Reform government of Edward Blake*. But his career in provincial politics had been ruined by his association with the Conservatives, and he was not asked to join the cabinet by either Blake or Oliver Mowat*. Gradually his interest shifted to federal politics. Although he did not contest his seat in the federal election of 1872, he resigned from the Ontario legislature upon the passing of the “dual representation” act and returned to the commons in 1873 in a by-election in West Durham, a safe Liberal riding opened by Blake’s decision to sit for South Bruce. The booming voice which had earned him the sobriquet “Big Thunder” was effective artillery against the Conservatives during the Pacific Scandal of 1873. But, despite his experience and ability, Wood was not selected to join Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberal cabinet, formed in November 1873.

In financial difficulty as a result of his luxurious style of living and sometimes dissolute behaviour, Wood accepted in March 1874 the office of chief justice of Manitoba, which carried a stipend of almost $5,000 per annum. For the next eight years Wood was a controversial figure on the Manitoba bench. From his first trial, that of Ambroise-Dydime Lépine*, Louis Riel’s lieutenant in the resistance of 1869–70, he sought to reassert the authority of the bench and the supremacy of British institutions in the province. After an impressive début, however, his stature quickly diminished as he became embroiled in local political disputes, federal-provincial railway controversies, and potential conflicts of interest with John Christian Schultz*, from whom he had borrowed money for his palatial residence in Winnipeg. “He is beyond question the making of an excellent Judge,” wrote Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris, “if he would only put on the dignity & impartiality of the Judge, and confine himself to his own sphere.” Wood failed, however, to adjust his temperament to the neutrality demanded of the bench. Even polished, learned, and well-reasoned judgements in a series of important cases could not restore a reputation tarnished by fits of temper and the occasional bout of intemperance.

In March 1881 Wood’s enemies among the local lawyers and politicians, including Joseph Royal* and Henry Joseph Clarke, petitioned the federal government for his removal on the grounds of partiality, dishonesty, and insobriety. He was now a pathetic figure, partially paralysed by a series of strokes, with poor hearing and barely coherent speech. On 7 Oct. 1882, before the charges levied against him could be fully investigated, Wood collapsed on the bench and died later that evening. He was survived by his wife, four sons, and two daughters, whom he left in the precarious financial circumstances to which he had been accustomed for most of his life.

Wood was a man of great intellect and learning, and his abilities were rarely questioned. In his native province he became a qc and bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada, and in Manitoba he was named to the presidency of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba. Yet he was headstrong and impatient, and earned a reputation for opportunism and venality that belied the evangelical Christianity to which he adhered as a low churchman of the Church of England. Few of his accomplishments were truly enduring, and the praise heard after his death was spare and restrained. “For those who were disposed to criticise adversely the judicial career of Chief Justice Wood,” read an obituary, “it will be well to remember that it fell to his lot to do the chopping, slashing and clearing, so to speak, of a new country. And if the work was not ornamental or artistic, it was at least useful.”

Edmund Burke Wood was the author of Arguments of Hon. E. B. Wood, before the arbitrators, under the British North America Act of 1867 . . . (Toronto, 1870); Mr. Wood’s argument before the provincial arbitrators on the modes proposed for the apportionment of the excess of debt and division of assets between Ontario and Quebec (Toronto, 1870); Petitions and reply to the charges preferred against the Hon. E. B. Wood, C. J., Province of Manitoba (Ottawa, 1882); Speech . . . delivered on the 15th December, 1868, in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario . . . (Toronto, 1869); and Speech . . . delivered on the 10th December, 1869, in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario . . . (Toronto, 1869). Some of his legal decisions as chief justice of Manitoba are found in Judgments in the Queen’s Bench, Manitoba, comp. Daniel Carey (Winnipeg, 1875; repr. Calgary and New York, 1918), and Reports of cases argued and determined in the Court of Queen’s Bench in Manitoba both at law and in equity . . . during the time of Chief Justice Wood, from 1875 to 1883 . . , ed. E. D. Armour (Toronto and Edinburgh, 1884).

AO, MU 136–273. PAC, MG 24, B40; MG 26, A. PAM, MG 12, B; E. QUA, Alexander Mackenzie papers. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), (1882): 529–30. The Canadian legal directory: a guide to the bench and bar of the dominion of Canada, ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1878). Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, I. [R.] D. and Lee Gibson, Substantial justice: law and lawyers in Manitoba, 1670–1970 (Winnipeg, 1972). R. St G. Stubbs, “Hon. Edmund Burke Wood,” HSSM Papers, 3rd ser., no.13 (1958): 27–47.

Cite This Article

J. Daniel Livermore, “WOOD, EDMUND BURKE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_edmund_burke_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_edmund_burke_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. Daniel Livermore |

| Title of Article: | WOOD, EDMUND BURKE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 26, 2025 |