Source: Link

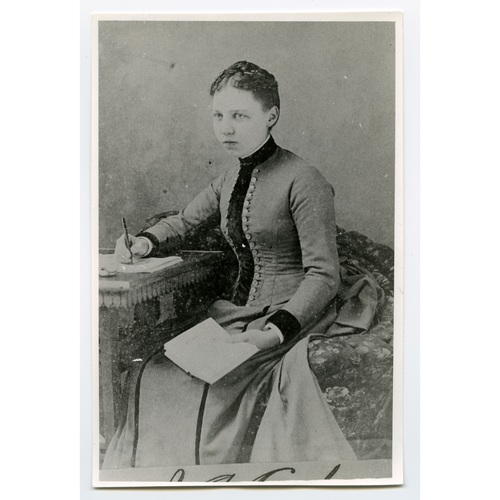

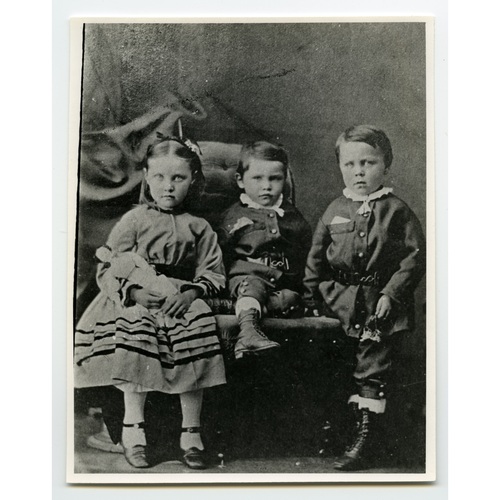

ADDISON, MARGARET ELEANOR THEODORA, educator, diarist, and first dean of women at Victoria College, Toronto; b. 21 Oct. 1868 in Horning’s Mills, Ont., eldest of the five children of the Reverend Peter Addison and Mary Ann Campbell; d. unmarried 18 Dec. 1940 in Toronto.

Margaret Addison, the daughter of a Methodist Church of Canada minister and a former schoolteacher, was profoundly influenced by her parents’ belief in education as a moral and spiritual guide. The family moved every three years as was required by the Methodist itinerancy rule. Margaret started high school in Richmond Hill, Ont., and finished in Newcastle. In 1885 she entered what was then Victoria University in Cobourg, which was under the direction of Samuel Sobieski Nelles* and then Nathanael Burwash*. The sixth woman to graduate from Victoria, Addison completed her ba in modern languages in 1889 and won the silver medal. She taught mainly mathematics and chemistry at the Ontario Ladies’ College in Whitby (1889–91) before becoming a specialist in French and German at Stratford Collegiate Institute (1892–1900) and Lindsay Collegiate Institute (1901–3).

Among the disincentives to higher education for young Methodist women at that time was their parents’ reluctance to lodge them in boarding houses (especially after Victoria’s move to Toronto in 1892 following its federation with the University of Toronto). By 1895 Margaret Burwash, wife of Victoria College’s president, had proposed the building of a women’s residence – a well-run home to which parents could entrust their daughters. Addison was among Mrs Burwash’s most avid supporters. She wrote letters, made speeches, and declared herself “willing to do anything righteous to help the Residence on.” In 1896 Hart Almerrin Massey* left $50,000 in his will for the project. The following year a memorial association named for Methodist Barbara Heck [Ruckle*] was set up to raise more funds, and in 1898 the task was taken on by the Victoria College Alumnae Association, with Addison as president.

In 1900, between teaching positions, Margaret spent several months travelling in Europe with her sister, Mary Agnes Charlotte W., culminating in a six-week visit to Cambridge and Oxford, England. There she made an intensive study of the women’s colleges, gathering ideas for Victoria’s residence and perhaps preparing herself should she be asked to serve in it. Always a prolific writer of diaries, letters, and reports, she kept a detailed journal in which she recorded her admiration for the communities of educated women she encountered. She responded enthusiastically to the college heads she interviewed, and would later speak of herself as “the humble disciple of these great leaders.”

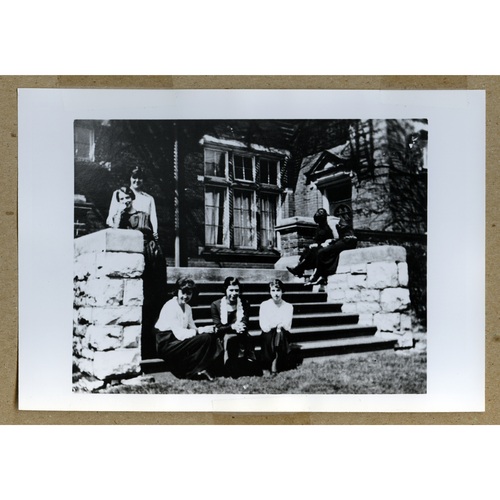

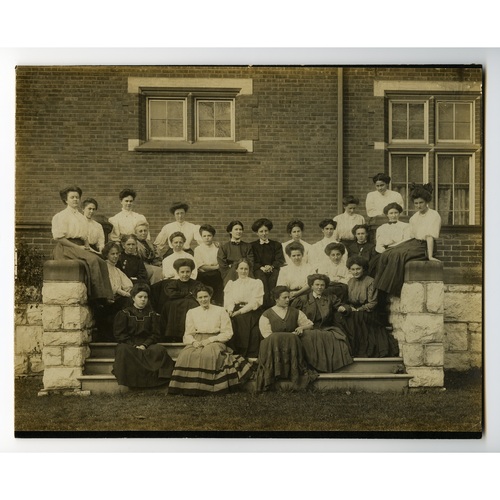

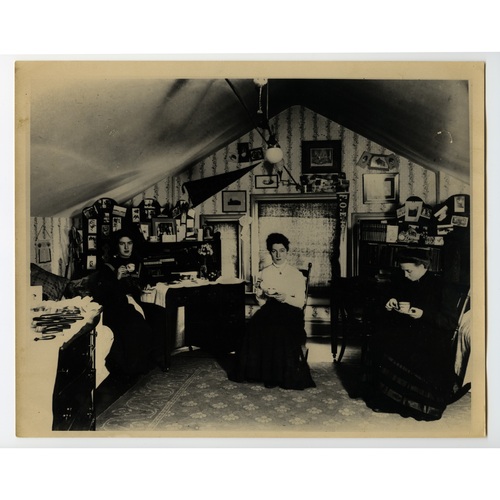

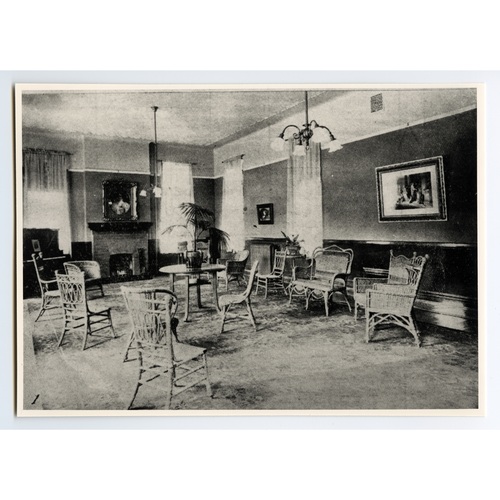

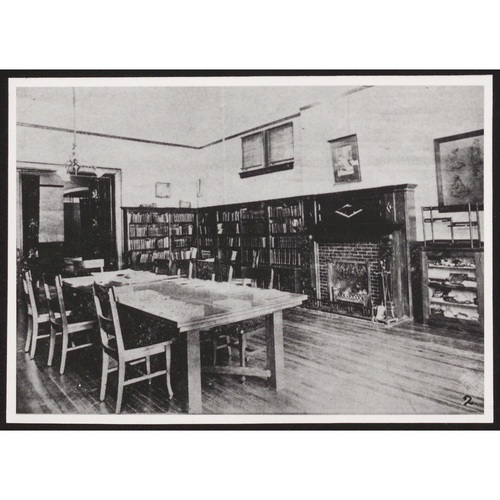

Annesley Hall, the first university residence for women in Canada, was eventually completed in 1903, and Addison was appointed its dean. For close to three decades she would tread a fine line, ensuring the acceptance of women’s university education by a cautious church while working to create a cultural and spiritual milieu that would widen the students’ horizons. At the outset, routines and rules of conduct were laid down. Meals were formal, with prayers after breakfast and dinner, and lights had to be out by 11:00 p.m. The purity of the young charges was strictly guarded. The main doors were locked after dinner; one could leave for the evening only if granted permission, which depended on such matters as destinations and suitable chaperones. Gentlemen were allowed to step inside on the second and fourth Friday evenings of the month, or on Sundays after church.

Some students rebelled against the regime. As Addison reported to the women’s Committee of Management, the first year was a disaster, with disobedience and selfishness rampant. Consequently, Addison experimented with student accountability during the following two years, and in 1906 instituted the Annesley Student Government Association, which made the residents partly responsible for modifying and administering the rules. Part of her mandate was to educate young women in citizenship, and she believed that the ASGA would contribute to that goal. Likewise, she arranged for guest speakers, among them British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, palaeobotanist Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes, and James Shaver Woodsworth*, a Methodist minister who worked among the poor in Winnipeg. Addison also escorted the girls to concerts and plays, fostered art appreciation, and promoted physical education, which was directed by Emma Priscilla Scott.

Margaret Addison’s career was buffeted by other storms and stresses besides student insubordination. Believing that a teaching appointment at Victoria College would solidify her authority, she accepted a position as lecturer in German in January 1906, becoming one of the first female university lecturers in Canada. Unfortunately, owing to misunderstandings about her status and remuneration, she taught for less than two years; subsequently her inclusion on the faculty list was merely nominal. Her leadership came under scrutiny in 1911–12 when Burwash launched an investigation into allegations of laxity: that girls visited each other’s rooms until midnight and flitted to dance halls unchaperoned. But Addison, supported by the alumnae association, successfully defended her regime and the student government, and gained authority over officers of the hall who had previously reported to the Committee of Management. In 1920 there was a restructuring of the residence – an apparent attempt to end Addison’s rule, which was judged old-fashioned chiefly by Charles Vincent Massey*, then dean of the men’s residence, and Alice Stuart Massey, his wife, a member of the Committee of Management. Addison was made dean of women, responsible for all the female students of the college. She was given a salary of $2,500 (which compared favourably with the $700 plus residence she had started with in 1903) but was required to vacate her rooms in Annesley Hall. The building was divided up and partly given over to non-boarding students, thus diminishing the original ideals of home and community. The arrangement did not prove satisfactory; to Addison it was an example of “the autocracy of men in the affairs of women,” whereas “Victoria College should lead in the idea that women know better how to manage women’s education than men.” By the fall of 1921 Addison was back in Annesley, and Alice Massey resigned from the committee.

The outcomes of these two controversies suggest that Addison was successful in finding a middle way. As she explained in a 1922 report, women were on sufferance in institutions such as the university: “They could never be in advance of public opinion concerning their freedom. But as public opinion changed, so could their freedom expand.” She was able to move with the times, countenancing dancing in the residence in 1926 and progressively loosening the rules. Whatever the future role of women, she believed that knowledge and training were key and that in all their endeavours women should use their particular strengths and gifts.

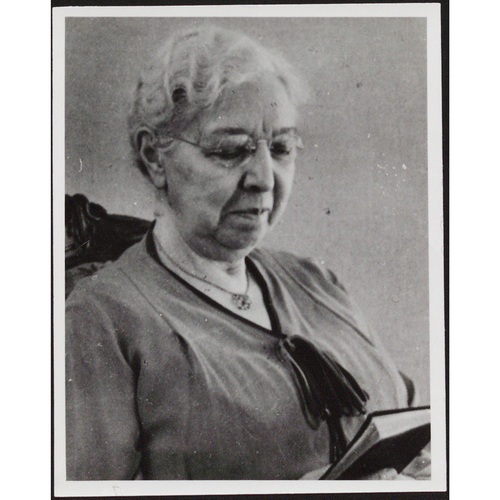

Throughout her years at Annesley, Addison remained active in the Victoria College Alumnae Association and in the University Women’s Club. She had also maintained her connection with the Ontario Ladies’ College and was a member of the Ontario Educational Association. After retiring in 1931 she continued her work with the Young Women’s Christian Association, the Woman’s Missionary Society, and the United Church of Canada, of which the Methodist Church had become a part in 1925 [see Samuel Dwight Chown].

Addison’s contributions to women’s education were eventually recognized: she was awarded an honorary lld by the University of Toronto in 1932 and was appointed a cbe in 1934. Most important, Annesley Hall would provide a model and guide for many future women’s residences in Canada. At the age of 72, after years of suffering from headaches and nervous prostration, Addison died of a cerebral haemorrhage. Yet at Victoria College, where Annesley continues to house female students, her legacy lives on, in the Margaret Addison Scholarship for women pursuing postgraduate studies outside Canada and in the name of another residence opened in 1959 – Margaret Addison Hall.

Margaret Eleanor Theodora Addison is the author of Diary of a European tour, 1900, ed. Jean O’Grady (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1999). She also wrote several journal articles, the most substantial being, in Acta Victoriana (Toronto), “Education and our relation to it as graduates,” 22 (October 1898–May 1899): 497–501; “Glimpses of education in Europe,” 24 (October 1900–May 1901): 301–4; and “Some women’s colleges,” 28 (October 1904–June 1905): 516–18; and, in the Missionary Monthly (Toronto), articles on Japan published in January 1933: 9–11; March 1933: 105–7; April 1933: 157–59; May 1933: 200–2; and a 9-pt. ser., “In time of war prepare for peace,” published between October 1936 and January 1941.

Private arch., Elizabeth McGregor (St Catharines, Ont.), “The book of the Addisons,” 2 vols. Victoria Univ. Arch. (Toronto), Fonds 2067, 90.141V, ser.1, boxes 1–2; ser.2, box 3; Fonds 2069, 90.064V, ser.2; Fonds 2097, 87.168V. Gertrude Rutherford, “Dean of women,” United Church Observer (Toronto), 15 Jan. 1941: 22, 29. In memoriam Margaret Addison, 1868–1940 (Toronto, 1941). Jean O’Grady, Margaret Addison: a biography (Montreal and Kingston, 2001). J. M. Selles, “Margaret Addison and Annesley Hall,” in her Methodists and women’s education in Ontario, 1836–1925 (Montreal and Kingston, 1996), 182–207. C. B. Sissons, A history of Victoria University (Toronto, 1952).

Cite This Article

Jean O’Grady, “ADDISON, MARGARET ELEANOR THEODORA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/addison_margaret_eleanor_theodora_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/addison_margaret_eleanor_theodora_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean O’Grady |

| Title of Article: | ADDISON, MARGARET ELEANOR THEODORA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |