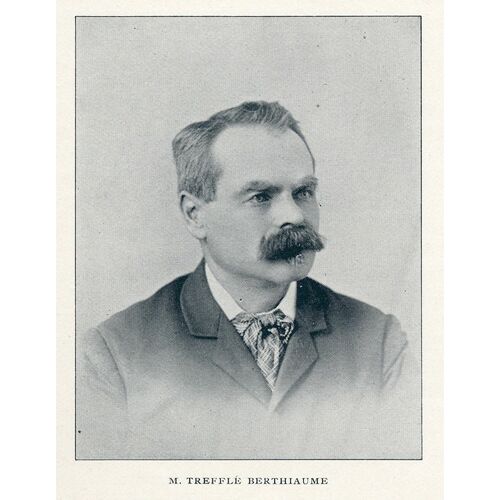

BERTHIAUME, TREFFLÉ (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Trefflé), newspaperman and politician; b. 4 Aug. 1848 in Saint-Hugues, Lower Canada, son of Gédéon Berthiaume, a joiner, and Éléonore Normandin; m. 21 Aug. 1871 Elmina Gadbois in Montreal, and they had five daughters and three sons; d. 2 Jan. 1915 in Outremont, Que.

One of five children born to Gédéon Berthiaume and his second wife, Trefflé Berthiaume was only four years old when his father died at the age of 39. In 1859, after primary schooling in his village, he was admitted to second year (Syntax) at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. His academic record was mediocre in the year he spent there. He was apprenticed to a tailor for more than two years, and then in March 1863 he began training as a typographer with the Lussier brothers (Camille, Isidore, and F.-X.-N.-Norbert), who owned Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe. When F.-X.-N.-Norbert Lussier left in July 1863 to start Le Messager de Joliette, Berthiaume went with him. Single-handed, he did the typesetting, printing, and distribution until the paper ceased publication in 1865. Next he went to Montreal and worked briefly for John Lovell* and subsequently at La Minerve. Back in Joliette, where Adolphe Fontaine began publishing La Gazette de Joliette in April 1866, Berthiaume worked as a typographer for two years, and then went to rejoin his family in the United States. On his return late in 1868, he was employed for two months in the printing plant of the Montreal Witness before he took up a job at La Minerve again early in 1869. In November 1871 he won a typesetting competition, which established his reputation for skill in this trade. He was made foreman of the typesetting department at La Minerve in 1872. Two years earlier he had been a founding member of the Union Typographique Jacques-Cartier, which organized the French-speaking typographers in Montreal affiliated with the International Typographical Union. He was recording secretary of this Montreal union in 1872 and president in 1882–83.

In 1879 Berthiaume and Napoléon Sabourin, a fellow typographer at La Minerve, assumed responsibility for typesetting and printing it. The contract, which was signed on 21 October, stipulated that the owner of this Conservative daily, Dansereau et Compagnie, would provide the equipment and material for the printing plant and pay for the paper and the rent for the building. For their part, Berthiaume and Sabourin undertook to provide heat and lighting for the premises where the two editions were typeset and run off. In addition, Dansereau et Compagnie would lease them the typesetting department for 7.5 per cent of its gross revenue, which came from business that included printing jobs for the Conservative governments in Ottawa and Quebec. The agreement, renewed in 1881 but cancelled in January 1883, was profitable for Berthiaume. In January 1884, with lithographer George J. Gebhardt and others, he founded the Gebhardt and Berthiaume Lithographing and Printing Company Limited with the accumulated capital. Berthiaume invested $4,000 of the firm’s initial $25,000. He managed the business until early in the 1890s, but seems to have withdrawn from it before it went bankrupt in 1894. On 10 May 1884, in partnership with Sabourin, he launched Le Monde illustré, a magazine intended to take the place of L’Opinion publique, which had ceased publication in 1883. For nearly a quarter of a century, the new periodical would play a leading role in the dissemination of French Canadian literature.

On 12 July 1889 Berthiaume signed a lease with La Minerve on terms that were very different from those of 1879 and that would soon prove intolerable. He was authorized to publish for his own gain a newspaper that had been running up debts for a number of years; in return he would pay an annual rent of $400 for the first two years, $800 for the next three, and $1,200 for the remaining 20. Berthiaume took charge of the administration, editing, printing, and distribution of the paper, leaving the Compagnie de Publication de La Minerve responsible only for the political thrust of editorial policy, which remained in the hands of Joseph Tassé*. The profitability of the daily was uncertain, but Gebhardt and Berthiaume Lithographing and Printing Company Limited, which Berthiaume represented in this transaction, could count on printing contracts from the federal government and from railway companies. Shortly thereafter, Berthiaume accepted a similar offer from Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* involving the daily La Presse. The contract, signed 19 Nov. 1889, covered a 25-year period and contained a clause allowing Berthiaume to purchase the newspaper at any time during the first ten years of the lease for $23,404.26 plus the rent for the building. He took charge of the administration, editing, printing, and distribution of La Presse, which was to be printed by Gebhardt and Berthiaume. Chapleau kept responsibility for political direction, which was entrusted to Guillaume-Alphonse Nantel*, and even secured a clause allowing him to retain editorial control in the event that Berthiaume purchased the daily. Berthiaume tried to realize the economies of scale made possible by publishing morning and afternoon papers. He carried the same up-to-the-minute news in the two dailies, solicited advertising for both, and set and printed them in the same premises.

The terms of the lease for La Minerve were less favourable than those for La Presse, and from early in the 1890s he sought in vain to get out of the contract. In August 1890, after Tassé had refused to let his salary be substantially reduced, Berthiaume made a number of decisions with a view to improving the paper’s financial situation. With his cousin Rémi Tremblay, he set up a company to replace the Compagnie de Publication de La Minerve as publisher. He took over the printing of the paper from Gebhardt and Berthiaume and on 8 September he unceremoniously dismissed Tassé, thereby saving his $3,000 salary. Tassé immediately sued Berthiaume, who lost the case but appealed the ruling. Early in June 1891 the two patties reached a mutually satisfactory agreement. Tassé resumed his place at the editorial desk of La Minerve, while Berthiaume was released without penalty from his obligations to the paper. This matter settled, Berthiaume continued working to make La Presse prosper. By 1890 it had shown a modest profit, which increased appreciably over the following years. On 7 Feb. 1894 he took over ownership from Chapleau, who was becoming more circumspect since his appointment as lieutenant governor of Quebec. During the 1890s Berthiaume tried to reproduce in Montreal approaches that were highly successful in the United States: he devoted more space to current events, gave more importance to brief news items, increased the number of pages, and introduced illustrations and headlines in large type. These changes proved popular, and the readership of La Presse rose from 17,000 in 1890 to more than 60,000 by the end of the century. In the mid 1890s, when its circulation surpassed that of the Montreal Daily Star, it became the largest newspaper in Canada.

On 16 Nov. 1896 Berthiaume was named legislative councillor for the division of Alma. Assiduous but discreet, he made it a point of honour to support the Conservative party, which had appointed him. The victory of Wilfrid Laurier in the 1896 federal election and of the Liberal party in Quebec in 1897 was followed by a realignment of political forces in the province, to which Berthiaume’s La Presse contributed actively. Chapleau’s death in June 1898 freed the paper from any political obligation to the former Conservative leader; in any case, Chapleau had already been calling for an alliance of Conservative and Liberal moderates in the province, which would have made it possible to oust the ultramontanes and radicals. Since 1897 Arthur Dansereau had been using his influence with the owner of La Presse to advance this point of view. In 1899 he left the post office in Montreal to become the editor, with the intention of bringing La Presse into the Liberal fold. Blunders committed by the leadership of the federal Conservative party during the 1900 election facilitated the rapprochement. Given the failure of Nantel’s La Minerve and aware that Berthiaume’s La Presse lacked conviction, the Conservative leaders had decided in December 1899 to launch a morning daily devoted solely to the interests of the party [see Louis Beaubien]. Berthiaume had persuaded them to protect the afternoon market of La Presse and had agreed to purchase $2,000 worth of shares in Le Journal. His bitterness about the role in setting up the new paper played by Hugh Graham*, who owned the Montreal Daily Star, the chief competitor of La Presse, was exacerbated by the strategic primacy given to the English-language daily by the Conservative party in the 1900 election. During the campaign, La Presse did not support the Conservatives and adopted a benevolent neutrality towards Laurier. Subsequently, in reprisal, the Conservatives decided to bring out Le Journal in the afternoon. It was a futile gesture and within weeks, at the end of February 1901, they had to resume publishing in the morning. Either through Dansereau or directly, Berthiaume gave Laurier to understand that his government could count on the backing (even more powerful for being discreet) of the largest French-language daily in North America. This support was not disinterested, for Berthiaume wanted to make his paper the national daily of French Canadians, wherever they might be in North America. He estimated that there were nearly two million francophones living in the United States, Ontario, and the Maritimes, but with high postal rates it was difficult for La Presse to reach them. Berthiaume and Dansereau made many approaches to the prime minister and the postmaster general, and in 1903 they obtained a substantial reduction in the rates. The Canada–United States postal agreement of 1907 and the amendments made to it in 1908 reduced the advantages of the previous rate but the changes did not erect an insuperable barrier to the circulation of Canadian dailies south of the border. The results were convincing. The American edition of La Presse grew from 8,000 copies in 1900 to more than 25,000 in 1907 and nearly 35,000 in 1914.

Berthiaume also turned to influential politicians for help in raising the capital needed for the expansion of his newspaper. During the 1890s he had had to invest large sums to increase the output of his printing plant, and the building that housed the enterprise had become cramped and obsolete. In 1900 the La Presse Company was incorporated, with a share capital of $750,000, and he bought a lot at the corner of Rue Saint-Jacques and Rue Saint-Laurent on which to put up a building specially designed for La Presse. Federal politicians, including Laurier and Senator George Albertus Cox, used their connections to enable him to consolidate his debts over a long period on favourable terms. Other less fortunate occurrences soon demonstrated to Berthiaume the importance of having well-placed political friends. On the eve of the 1904 federal election, La Presse was at the centre of a widespread plot against the Liberal government hatched by David Russell, a financier with interests in railways, and Hugh Graham. They were opposed to Laurier’s railway policy, which favoured the Grand Trunk, and they concocted a complex scheme aimed at discrediting the Liberals and bringing back the Conservatives, from whom they hoped to receive benefits. A central feature of this plan was the purchase of large Liberal newspapers, which at the appropriate time would be used to criticize the government. Russell, Graham, and James Naismith Greenshields*, a Montreal lawyer with connections to the Liberal party, managed to persuade Berthiaume to sell them his paper. During the night of 12 Oct. 1904 Russell gained ownership of La Presse for $700,000 and an agreement to pay off debts totalling $125,000. The Liberals got wind of the plot and Laurier threatened to expose it if Russell and Graham carried out their plan. Deprived of the financial support they had counted on and short of ready cash after the Liberal victory at the polls, Russell, Graham, and Greenshields had to accept an offer from Toronto financiers Donald Mann* and William Mackenzie*, who acquired control of the company. The reasons behind Berthiaume’s decision to give up the paper to which he had devoted some 15 years of hard work are still not clear, but it seems quite unlikely that he wished Laurier any harm. On the day he signed the documents for the sale (which he claimed, not very convincingly, had been extorted from him under the influence of alcohol), Berthiaume regretted the deal. “I realize now what a mistake I have just made. Before, I held in my hands an extremely powerful instrument that obeyed my will, and I was a force [to be reckoned with]. Now, all I have is a bank passbook, and all I will have to do for the rest of my life is to write cheques!”

But Berthiaume was still the owner of L’Album universel, which had replaced Le Monde illustré in 1902, and he tried to make it as attractive a weekly as the best American magazines. He missed La Presse, however, and several times during the next few months he begged Laurier to intercede with the new owners to let him repurchase it on favourable terms. Laurier replied that Mackenzie and Mann would certainly agree to sell the paper back to him if the price was right. In February 1906 Berthiaume sold L’Album universel and the plant at which it was printed, probably in anticipation of buying back La Presse. On 1 November, in order to regain ownership of his newspaper, he was forced to swallow his pride. The price of $1,150,000 was $325,000 more than he had received when he sold it in 1904. In addition, since he was still in debt to Mackenzie and Mann for 20 years, and to David Russell for 10 years, Berthiaume had to submit to humiliating conditions: Mackenzie and Mann would appoint their own representative to the paper’s editorial board, Mann would countersign all cheques, invoices, and other financial documents, and an upper limit was set on the salaries of the editors as well as on those of the publishing company’s directors.

The ensuing years were especially difficult for Berthiaume because of the burden placed on La Presse and on his personal budget by his obligations to the newspaper’s creditors, and the strain was intensified by the unfortunate experience of the Saint Raymond Paper Company. In 1904 Berthiaume had contracted to buy newsprint from it, but construction of its mill was delayed and Berthiaume, who held a large part of its shares, agreed to co-sign its loans. The Canadian Bank of Commerce seized the mill in November 1907 and kept it running for more than a year without authorizing the investments that would have made it profitable. In addition to having to repay his debts related to La Presse, Berthiaume now had to assume those of Saint Raymond Paper. He sold several of his buildings and turned over a number of promissory notes to the bank, but he could not meet all his obligations, and in 1909 it sued him in Superior Court to recover some $160,000. The bank’s liquidation of the company in March 1909 brought him enough money to avoid imminent bankruptcy. Later on, thanks to a sizeable income from La Presse, whose circulation was now more than 100,000, his financial situation improved rapidly, and in 1911 he helped found British Canadian Paper Mills, which took over the assets of Saint Raymond Paper. In November 1913 he negotiated a loan on the London market and bought back Mackenzie and Mann’s shares in La Presse, of which he once again assumed sole control.

However, Berthiaume, who had suffered from arteriosclerosis for several years, felt his health beginning to deteriorate. He restricted his activities and took a long holiday in Europe from June to September 1913, but he did not get better. On 23 June, before his departure, he had dictated a will naming his eldest son, Arthur, his heir and trustee, with instructions to share the income from his property with the other children and their descendants. On 26 Dec. 1914, however, he signed a deed of gift in trust which turned over his shares in La Presse to lawyer Zénon Fontaine, notary Joseph-Roch Mainville, and Arthur, vesting them with the responsibility of administering the newspaper after his death and distributing the income from it to his children. Berthiaume’s death on 2 Jan. 1915 left his heirs uncertain of his final wishes. During the years that followed, his children, his sons-in-law, and the fiduciaries of La Presse would confront one another in the courts and before the Legislative Assembly over the diverse interpretations given these documents.

Trefflé Berthiaume had achieved exceptional success. Painstaking and industrious, he accumulated capital methodically and used it judiciously. A Conservative in the tradition of Dansereau and Chapleau, he was more interested in business than politics. He spent the first 15 years of his career managing Conservative newspapers on behalf of politicians or on his own behalf. He learned to take advantage of the rules of the day. Even when not operating at a loss, the newspapers made little profit, but the printing contracts that the parties in power awarded to papers supporting them were very lucrative. In the same way, large service enterprises such as the railways gave preference to the Conservative party’s newspapers in their advertising. A cautious man, Berthiaume could none the less take calculated risks. Although the era of the partisan press was closing, he did not spend time drawing earth-shaking conclusions from the trend but set La Presse firmly on the path of political independence and current news. He was determined to tie his paper’s success to the promotion of the interests of the working classes and the French Canadian people. As a devout Catholic, he had no objection to the archbishop of Montreal’s regular intervention in the content of La Presse. On the contrary, once its success was ensured, Berthiaume agreed to tone down its sensationalism. He was a tireless worker, but he was not greedy and could be generous to relatives, friends, and charitable organizations. He was well liked by his employees, though they knew he was demanding. Every day he read La Presse and its competitors and when necessary sent comments to the journalists, editors, or foreman. In addition to being a shareholder in a number of companies, he owned considerable property that included lots, commercial buildings, and rental housing in Montreal. With his son Arthur and others, in 1906 he founded a real estate business, the Quebec Land Company [see Édouard-Burroughs Garneau]. It was no doubt his success in this sector that enabled him to overcome the financial difficulties of the years from 1907 to 1909.

The richest source of information on Trefflé Berthiaume is his papers at ANQ-M, P-207, for which two finding aids, covering the manuscripts and the photographs, have been prepared. The Berthiaume fonds has also been made available on microfilm by the Société Canadienne du Microfilm.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 21 août 1871; CE2-17, 5 août 1848. Le Devoir, 15, 17–20, 22–24 févr. 1926. Le Passe-Temps (Montréal), 16 janv. 1915. La Presse, 2 janv. 1915. Charles Robillard, “Réminiscences d’un vieux journaliste: l’hon. Trefflé Berthiaume,” La Patrie, 15 sept. 1940 [éd. hebdomadaire]: 52. Jean de Bonville, La presse québécoise de 1884 à 1914; genèse d’un média de masse (Québec, 1988). Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), 2: 131. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Cyrille Felteau, Histoire de “La Presse” (2v., Montréal, 1983–84). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise. R. R. Heintzman, “The struggle for life: the French daily press of Montreal and the problems of economic growth in the age of Laurier, 1896–1911”

Cite This Article

Jean de Bonville, “BERTHIAUME, TREFFLÉ (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Trefflé),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/berthiaume_treffle_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/berthiaume_treffle_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean de Bonville |

| Title of Article: | BERTHIAUME, TREFFLÉ (baptized Jean-Baptiste-Trefflé) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 2, 2026 |

![M. Trefflé Berthiaume [image fixe] Original title: M. Trefflé Berthiaume [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.2681.jpg)