Source: Link

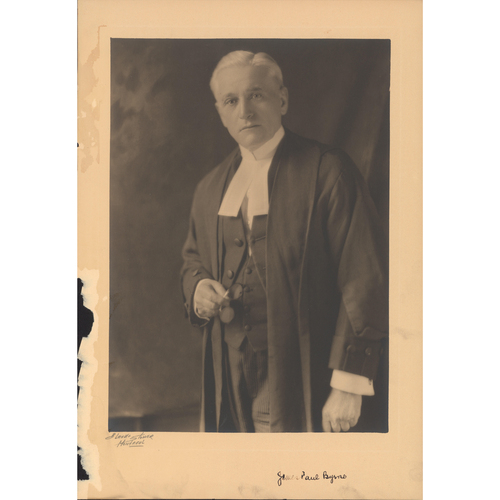

BYRNE, JAMES PAUL, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 24 Jan. 1869 in Sussex, N.B., son of James Byrne and Sarah Green; m. 16 Sept. 1902 Emma Josephine Burns (1872–1947), daughter of Kennedy Francis Burns*, in Bathurst, N.B.; they had no children; d. there 22 Jan. 1934 and was buried in Norton, N.B.

James Paul Byrne’s father emigrated from County Tyrone (Northern Ireland) to New Brunswick in 1842, and his mother, of English descent, was born in Halifax a year later; both were Roman Catholic. After attending local schools in Sussex, Byrne earned a ba in 1888 from the College of Saint Joseph in Memramcook [see Camille Lefebvre*], a francophone institution in southeastern New Brunswick that had become more and more anglicized. Accepted as a law student in Albert Scott White’s firm in October 1887, Byrne spent the 1888–89 academic year at Dalhousie law school in Halifax before transferring to the University of Michigan, home to one of the largest and most progressive law schools in the United States. In 1890 he graduated with an llb and two years later he was called to the bar of New Brunswick. Byrne then practised on his own in Sussex, a small and sleepy dairy-farming community in the province’s agricultural heartland. The area was overstocked with lawyers, however, and there was scarcely enough business for established members of the profession such as White, let alone a brand-new one like Byrne.

In 1900 Byrne relocated to Bathurst, a thriving seaport, industrial centre, and railway hub on the southernmost point of the Baie des Chaleurs. The Acadian peninsula was virtually a foreign country to him, since he had neither a personal connection with nor a first-hand knowledge of the region, but Bathurst offered a new frontier and a broader horizon for a young professional seeking to carve out a successful career. Before his arrival there was no Catholic lawyer to service the legal needs of Bathurst’s Acadian and Irish Catholics, who together formed the majority of the local population and were a social and political force to be reckoned with. Marrying one of the four daughters of the late Kennedy Francis Burns, an Irish Catholic who had been a prominent entrepreneur and politician, helped Byrne to establish himself quickly in a community bigger and busier than the one he had left.

Though a unilingual anglophone as his father-in-law had been, Byrne found that his lack of French was no obstacle to doing business with his francophone co-religionists or to gaining their respect, trust, and political backing. He also knew he could rely on the patronage and support of the Catholic hierarchy, particularly bishops James Rogers* and Thomas Francis Barry, whose diocese, then based in Chatham, embraced the entire north shore of the province. Indeed, it is possible that Rogers, who retired in 1902, recruited Byrne to serve as the diocesan solicitor and lawyer of choice for Catholics throughout Gloucester County. Byrne would live to see the centre of gravity in the diocese shift from anglophone Chatham to increasingly francophone Bathurst, especially after 1920, when an Acadian, Patrice-Alexandre Chiasson, succeeded Barry as bishop.

Byrne soon got involved in the county’s politics and won a place on its municipal council; he may have played a role in the incorporation of Bathurst as a town in 1912. In 1908 provincial politics beckoned, and Byrne won Gloucester as an independent Liberal in an election that saw the Liberal government of Premier Clifford William Robinson* go down to defeat. After losing his seat in the 1912 Conservative landslide led by James Kidd Flemming*, Byrne was returned five years later when the Liberals regained power under Walter Edward Foster*, and he was re-elected in 1920. He had no opportunity to run for the federal seat once held for the Conservatives by his father-in-law because it was continuously occupied by Onésiphore Turgeon*, a fellow Liberal, between 1900 and 1922. Byrne may have had hopes of a career in federal politics, but when Turgeon was appointed to the Senate he was succeeded by an Acadian Liberal in a by-election that the Conservatives did not even bother to contest.

Under Foster and Pierre-Jean Veniot, who would become premier in 1923, Byrne held the post of attorney general for seven years, the longest uninterrupted tenure since that of Andrew George Blair*. In 1917 Byrne and Foster supported the bill for women’s enfranchisement that was put forward by William Francis Roberts, but it was defeated in a free vote after Veniot led the charge against it. Two years later, however, the Foster government, with Byrne introducing the legislation, successfully implemented female suffrage in New Brunswick. In 1922 he declined to prosecute for a sixth time the accused child murderer John Paris, who had been conditionally discharged after the jury failed to reach a verdict in his fifth trial. A year later Byrne oversaw the passage of a blue-sky law for regulating securities, but the Supreme Court of New Brunswick ruled it unconstitutional in a dubious decision written by Chief Justice Sir John Douglas Hazen.

In September 1924 a vacancy on the bench was created by the resignation of Harrison Andrew McKeown as chief justice of the Court of King’s Bench of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick and the promotion of Jeremiah Hayes Barry*, one of the division’s puisne justices, to take his place. The choice of Byrne as Barry’s successor was practically inevitable. He was a Liberal politician and a long-serving attorney general at a time when the federal Liberals were in power under William Lyon Mackenzie King* in Ottawa and the former provincial Liberal leader, Arthur Bliss Copp, was New Brunswick’s representative in cabinet. Byrne was an Irish Catholic as well, and Barry had been the first Irish Catholic to sit on the Supreme Court. Yet it is also probable that Byrne’s appointment was a consolatory quid pro quo for his failure to become premier after Foster’s resignation in 1923. His claim to the succession had been at least as strong as that of Veniot, under whose leadership the government would be defeated in the election of 1925. Ivan Cleveland Rand* followed Byrne as Liberal member for Gloucester and attorney general.

James Paul Byrne proved himself a capable, effective, and respected judge. So great was the loss occasioned by his sudden death on 22 Jan. 1934, and so difficult was the task of finding an able lawyer with the requisite political credentials to replace him, that 19 months passed before the federal Conservative government of Richard Bedford Bennett* appointed Jack Hall Alliger Lee Fairweather, a former Conservative mha, as his successor. Byrne lived to see Albert Allison Dysart*, a fellow Irish Catholic lawyer and graduate of the College of Saint Joseph, chosen in 1926 as leader of the New Brunswick Liberals. In 1935 Dysart would become premier, the position that Byrne himself should have ascended to 12 years earlier.

James Paul Byrne’s commonly accepted birth date, 24 Jan. 1869, is indicated on his death record (PANB, RS141C5, vol.59, no.59360) and in most published sources; however, the 1901 census gives 24 Jan. 1871, and the 1911 census gives January 1870.

Byrne’s papers have not survived. He is the compiler of Bye-laws, rules and regulations of the county council of the municipality of Gloucester; also extracts from the statutes of New Brunswick published by order of the county council for the guidance of parish officers (Newcastle, N.B., 1907).

LAC, Census returns for the 1911 Canadian census, N.B., dist. Gloucester (27), subdist. Bathurst (5): 22; R233-37-6, N.B., dist. Gloucester (16), subdist. Bathurst (Parish) (A): 1. PANB, MC288 (Law Society of New Brunswick fonds), MS4, B2, Byrne, James P., 7 Oct. 1890; RS141B7, code B4/1902, no.1355. Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. & Special Coll. (Fredericton), MG H107. Freeman (Saint John), 1900–2. Gloucester Northern Light (Bathurst, N.B.), 1913–34. Kings County Record (Sussex, N.B.), 1901–34. New Freeman (Saint John), 1903–34. Canadian annual rev., 1917–34. “Dictionnaire biographique du nord-est du Nouveau-Brunswick,” [series of special issues], Soc. Hist. Nicolas-Denys, La Rev. (Shippagan, N.B.), 11 (1983), no.3; 12 (1984), no.3; 13 (1985), no.3; 15 (1987), no.1; 18 (1990), no.2; 20 (1992), no.2; 23 (1995), no.1; 26 (1998), no.2. Don Hoyt, A brief history of the Liberal Party of New Brunswick ([Fredericton, 2000?]). Michigan Alumnus ([Ann Arbor, Mich.]), 1894–1934. N.B., Legislative Assembly, Synoptic report of the proc., 1908–12, 1917–24.

Cite This Article

Barry Cahill, “BYRNE, JAMES PAUL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byrne_james_paul_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/byrne_james_paul_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | BYRNE, JAMES PAUL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |