Source: Link

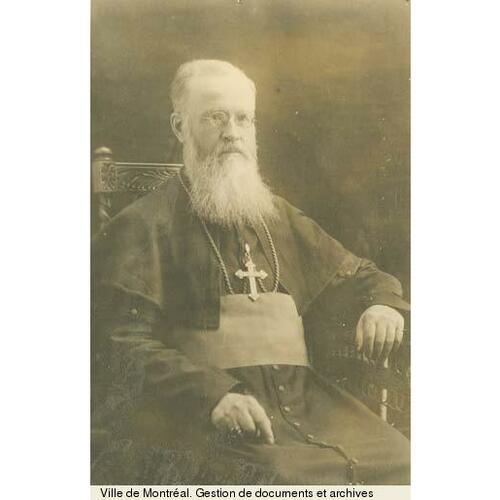

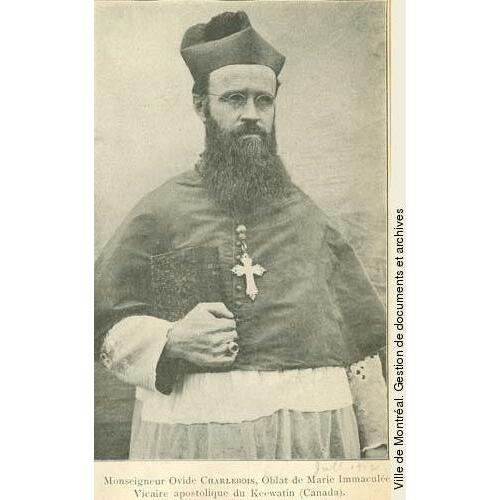

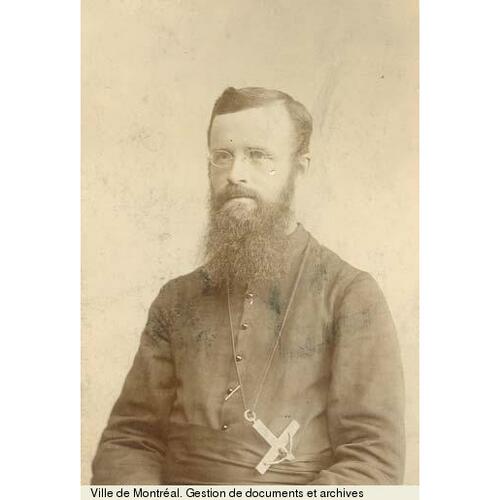

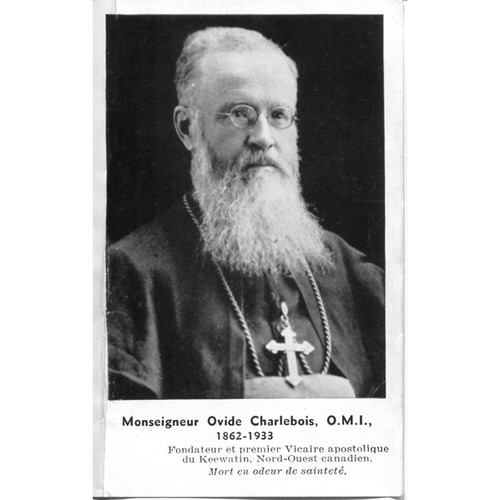

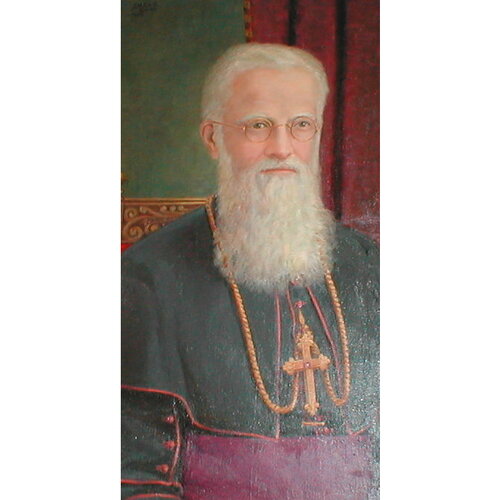

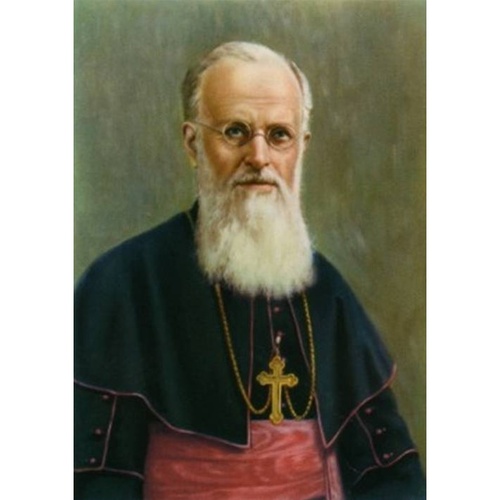

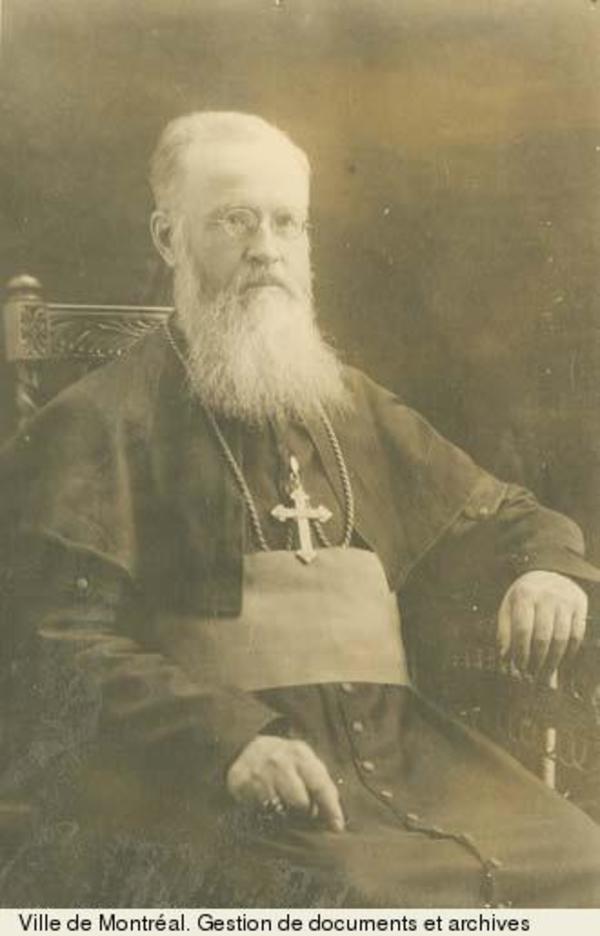

CHARLEBOIS, OVIDE (baptisé William-Ovide), père oblat de Marie-Immaculée, enseignant, administrateur scolaire et évêque, né le 17 février 1862 à Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes (Oka, Québec), fils d’Hyacinthe Charlebois et d’Émérente (Émérence) Chartier (Chartier-Robert) ; décédé le 20 novembre 1933 à The Pas, Manitoba.

Peu après sa naissance au Bas-Canada, Ovide Charlebois, septième de 14 enfants, partit vivre avec sa famille dans la localité voisine de Saint-Benoît (Mirabel), puis, en 1864, à Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson, au nord-ouest de Terrebonne. Ovide reçut une instruction rudimentaire à l’école du coin. De 1876 à 1882, il fréquenta le collège de L’Assomption ; il entra ensuite au noviciat oblat de Lachine (Montréal). Après avoir prononcé ses vœux simples, en 1883, il étudia la théologie et la philosophie au collège d’Ottawa et au scolasticat Saint-Joseph. Il fit sa profession perpétuelle en 1884, fut tonsuré deux ans plus tard et ordonné prêtre à Ottawa par l’évêque Vital-Justin Grandin*, du diocèse de Saint-Albert, le 17 juillet 1887.

En septembre, Charlebois amorça sa longue carrière de missionnaire à Cumberland House (Saskatchewan). Pendant qu’il était au noviciat, il avait exprimé le souhait de servir dans le Nord-Ouest canadien, mais il avait également mentionné sa crainte de la solitude. Ironiquement, pendant ses quatre premières années dans l’immense district de Cumberland, il ne passa jamais plus d’un mois et demi en compagnie d’un collègue oblat. En 1890, il ouvrit une école à Cumberland House, où non seulement il effectuait ses tâches missionnaires habituelles, mais il enseignait aussi quatre heures par jour. Il était toutefois obligé de voyager beaucoup pour apporter son ministère à la population dispersée d’Amérindiens et de Métis. Selon ses estimations, il aurait, pendant l’hiver de 1900–1901, parcouru quelque 3 000 milles en raquettes et en traîneau à chiens, et campé 35 fois dans la neige.

En 1903, Charlebois fut nommé directeur du pensionnat autochtone de Saint-Michel à Duck Lake. Outre qu’il enseignait le catéchisme en cri et soignait les malades, il s’efforça de réduire la dette de l’école, qui s’élevait à plus de 10 000 $, et d’améliorer ses installations. Comme d’autres à son époque, il croyait que les élèves autochtones connaîtraient un meilleur bien-être si on les soustrayait à l’influence de leur communauté. Cependant, les élèves qui résidaient à Saint-Michel vivaient dans des conditions insalubres et dangereuses, situation semblable à celle de nombreux autres pensionnats [V. Peter Henderson Bryce]. Cela entraînait des maladies et un taux de décès alarmant : à la fin des années 1910, une réserve voisine de Saint-Michel avait perdu près de la moitié de ses enfants qui avaient fréquenté cette école. Dans une proposition adressée au gouvernement fédéral en 1909, il suggéra de fonder une colonie agricole spéciale pour aider les élèves qui quittaient le pensionnat à devenir des fermiers autosuffisants. Il recommanda également de permettre aux plus avancés de travailler pour acquérir une expérience pratique : les garçons pourraient apprendre à exploiter une ferme et les filles à tenir maison. À titre d’expérience, le ministère des Affaires indiennes autorisa Charlebois à placer plusieurs jeunes filles, après leurs études au pensionnat, dans des foyers non autochtones, afin d’y travailler comme domestiques, et ce, malgré les protestations de leurs parents. On abandonna le projet seulement après qu’un agent des Affaires indiennes eut écrit à son ministère pour dénoncer la situation, qu’il décrivit comme « comparable à de l’esclavage ».

Pendant qu’il était à Duck Lake, Charlebois collabora à la création d’un journal catholique francophone pour répondre aux besoins de la minorité isolée de la province. En décembre 1908, lui et l’abbé Pierre-Elzéar Myre, de la localité voisine de Bellevue (Saint-Isidore-de-Bellevue), présentèrent le rôle et la politique du périodique et, avec d’autres membres du clergé, fournirent la mise de fonds initiale et lancèrent une campagne de souscription pour établir la Société de la Bonne Presse Limitée, compagnie qui chapeauterait la publication du Patriote de l’Ouest. Imprimé dans un atelier de menuiserie du pensionnat, celui-ci commença à paraître en août 1910 ; le rédacteur en chef en était le père Adrien-Gabriel Morice. En novembre, un incendie détruisit le matériel d’imprimerie, mais on reprit la publication du journal en juin 1911. Charlebois contribua également à rehausser le statut de la grotte de Saint-Laurent-de-Grandin (Saint-Laurent-Grandin) en faisant du pèlerinage au site un événement annuel pour les élèves ; les résidants du coin adoptèrent aussi cette pratique.

En 1907, la formation d’un nouveau vicariat apostolique, comprenant les parties septentrionales de la Saskatchewan, du Manitoba et de l’Ontario, avait été abordée comme moyen de faciliter le travail missionnaire. Adélard Langevin*, archevêque de Saint-Boniface, au Manitoba, avait déjà présenté la candidature de Charlebois à la direction de l’administration générale oblate. Le 4 mars 1910, Rome créa le vicariat apostolique du Keewatin et, le 8 août, nomma Charlebois évêque titulaire de Bérénice et vicaire apostolique. Le 30 novembre, à L’Assomption, au Québec, Langevin le sacra évêque. Malheureusement, l’administration oblate refusa la responsabilité du nouveau vicariat, parce qu’elle ne pouvait le doter d’un clergé suffisant pour lui assurer un fonctionnement convenable. Elle affirma n’avoir été consultée ni sur l’érection du vicariat, ni sur la nomination d’un évêque. Par conséquent, Charlebois fut forcé de consacrer du temps, de l’argent et des efforts considérables pour recruter du personnel et recueillir des fonds pour accomplir son travail apostolique.

Charlebois établit sa résidence épiscopale à The Pas, dans une cabane en rondins de 14 pieds sur 14. En mai 1911, il commença une tournée de cinq mois dans son vicariat, parcourant quelque 2 500 milles à pied, en canot, en chariot et en train pour visiter 14 missions et postes. En 1915, il divisa la vaste région en trois districts, chacun sous la direction d’un supérieur ; par la suite, il se rendrait chaque année dans l’un des districts à tour de rôle. Son arrivée à une mission créait une occasion de réjouissance et de célébration, marquée par des salves d’armes à feu. Ceux qui l’accueillaient s’agenouillaient alors pour recevoir sa bénédiction et une poignée de main, cérémonies suivies d’instruction religieuse, de sermons et d’administration des sacrements. Ces visites pastorales apportaient également beaucoup de consolation aux missionnaires oblats, car nombre d’entre eux n’avaient aucun collègue et ne pouvaient donc observer la règle de leur ordre en matière de vie commune.

L’éducation demeurait une grande préoccupation pour Charlebois, et il fut impliqué dans des controverses scolaires au Manitoba, en Ontario et en Saskatchewan. En 1912, lorsque le premier ministre du Manitoba, Rodmond Palen Roblin, réussit à obtenir une extension des frontières de la province vers le nord, à l’intérieur du district de Keewatin, Charlebois tenta en vain d’exercer des pressions auprès du gouvernement fédéral de Robert Laird Borden pour maintenir le droit constitutionnel des catholiques de la région de disposer d’écoles séparées subventionnées par des fonds publics. Il soutint l’Association canadienne-française d’éducation d’Ontario dans son conflit avec l’administration provinciale de sir James Pliny Whitney* au sujet du Règlement 17 [V. Ovide-Arthur Rocque*]. Les écoles publiques de la Saskatchewan relevant de son vicariat seraient assujetties à la loi qui interdirait le port de costumes et de symboles religieux, sanctionnée en 1930 par le premier ministre James Thomas Milton Anderson*. Même s’il ne possédait pas la verve de Langevin, son métropolitain, Charlebois défendit sans relâche les droits des catholiques de langue française dans un certain nombre d’affaires, notamment sur la question des nominations épiscopales en Ontario et dans l’Ouest canadien, la création de nouveaux diocèses, la fondation de l’Association catholique franco-canadienne de la Saskatchewan en 1912, les protestations contre le contenu des manuels dans les écoles secondaires du Manitoba et les pétitions pour rétablir le nom original de Le Pas, localité constituée sous celui de The Pas cette année-là.

Étant donné son emplacement nordique, le vicariat du Keewatin était idéalement situé pour promouvoir l’évangélisation des Inuits de l’Arctique canadien. En 1911, Charlebois demanda à l’oblat Arsène Turquetil* d’explorer la région et d’évaluer son potentiel pour la fondation de missions. En septembre de l’année suivante, Turquetil commença à construire une mission dans le hameau de Chesterfield Inlet (Nunavut), qui deviendrait la mission catholique la plus importante de l’est de l’Arctique. Charlebois autorisa la mise sur pied d’une mission à Eskimo Point (Arviat) en 1925 et planifia l’érection d’autres missions qui ne se concrétisa jamais, car l’est de l’Arctique fut retiré de son autorité en 1925 et transféré à la nouvelle préfecture apostolique de la baie d’Hudson. Cette décision le perturba profondément, parce qu’il n’avait pas été consulté.

La découverte et l’exploitation de minerais et d’autres ressources naturelles dans la région au milieu des années 1920 transformèrent la nature du vicariat de Charlebois. L’établissement de mines, de fonderies, de projets hydroélectriques et du Hudson Bay Railway attira une forte population blanche et de nouvelles missions durent être construites. Même si la population autochtone n’augmenta que légèrement pendant le ministère de Charlebois – elle passa d’environ 10 000 personnes à 11 150 en 1933 –, la population non autochtone d’une centaine de personnes grimpa à 11 500. Cet afflux entraîna de graves problèmes sociaux et l’évêque dénonça l’influence pernicieuse des nouveaux arrivants sur les autochtones, exhortant son clergé à combattre « ces puissantes sources de perversion et de dépravation ».

Comme résultat des initiatives de Charlebois, le nombre de missions de son vicariat passa de 9 en 1911 à 19 en 1933, et celui des membres du clergé et des religieux tripla. Malgré son âge avancé, il continua d’entreprendre des visites pastorales éreintantes. En 1923, par exemple, il avait parcouru 1 000 milles en canot, franchi 80 milles de portages et dormi 23 nuits à la belle étoile. Il visita sept missions, prêcha des retraites de cinq à sept jours à quelque 2 500 membres des Premières Nations et administra la confirmation à 220 personnes. En 1927, au retour d’une visite d’un mois aux missions de Norway House et de Cross Lake, au Manitoba, son bateau faillit chavirer deux fois dans le lac Winnipeg. Il avoua être épuisé. Pendant la période de 1911 à 1922, il avait accompli cinq voyages à Île-à-la-Crosse, en Saskatchewan, pour prêcher des retraites d’une semaine ou pour offrir de l’instruction religieuse.

Charlebois manifesta une préoccupation constante pour l’éducation des autochtones et cherchait à leur offrir plus que ce qui était enseigné dans les écoles rudimentaires de mission. Par conséquent, il commença à adresser des requêtes au gouvernement fédéral pour la création de pensionnats amérindiens et, après des efforts considérables, réussit à en obtenir deux nouveaux : à Cross Lake, au Manitoba, et à Sturgeon Landing, en Saskatchewan. Il caressait de grands espoirs pour ces établissements et celui de Beauval, fondé en 1895, qui allait servir de scolasticat, mais qui, le 19 septembre 1927, fut rasé par un incendie dans lequel disparurent une religieuse et 19 élèves. La perte financière fut évaluée à 50 000 $. Charlebois commença la reconstruction à ses frais en attendant de l’aide du gouvernement. En 1930, les élèves mirent le feu à l’école de Cross Lake ; une religieuse et 11 élèves périrent.

Au cours des dernières années de son existence, Charlebois devint obsédé par le communisme, qu’il condamnait fermement. Pendant l’assemblée générale des évêques canadiens à Québec, en 1933, il tomba malade. À son retour à The Pas, il fut admis à l’hôpital, où il mourut à 71 ans.

Outre qu’il parlait couramment le cri et le chipewyan, Charlebois était un menuisier habile qui construisit des chapelles, des écoles et des pensionnats, de même que sa résidence épiscopale et la cathédrale à The Pas. Il fut toujours une personne très humble. En 1905, conformément aux préceptes de pauvreté et d’abnégation, il s’était retenu de rendre visite à son père mourant et d’assister aux funérailles. Pour son propre service funèbre, il demanda avec insistance un enterrement de pauvre ; son cercueil coûta 40 $. Sa cause de béatification fut amorcée en 1951 et soumise à Rome en 1953.

Ovide Charlebois gouverna un vicariat vaste et isolé, dans un climat rude ; ces facteurs, qui compliquaient les voyages ainsi que l’établissement de missions, les exposèrent, lui et les missionnaires, à des difficultés incroyables. Dépourvu de prétentions matérielles, Charlebois admirait les vertus de pauvreté, d’humilité et de mortification. Il considérait l’extension du royaume de Dieu comme relevant de son devoir et il le fit sans chercher de reconnaissance ou de louanges. Son œuvre renferme toutefois des épisodes regrettables, comme en témoignent les conditions de vie au pensionnat autochtone de Saint-Michel pendant son directorat.

Ovide Charlebois est l’auteur de « Vicariat du Keewatin : Mgr Charlebois, O.M.I., en tournée pastorale », Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée (Rome), 53 (1919) : 277–292 et de Mgr O. Charlebois, o.m.i., v.a., chez les Esquimaux : notes de voyage, visite pastorale, ordination, etc. (Ottawa, [1923]). Il a aussi écrit, en collaboration avec Arsène Turquetil, Débuts d’un évêque missionnaire : Mgr Ovide Charlebois, O.M.I., évêque de Bérénice, vicaire apostolique du Keewatin : prise de possession, installation, première visite pastorale des missions sauvages (Montréal, s.d.).

Arch. Deschâtelets, Oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Ottawa), H 5201-5250 ; LC 6001-8000.— Le Patriote de l’Ouest (Prince Albert, Saskatchewan), 21 févr. 1923.— Gaston Carrière, Dictionnaire biographique des oblats de Marie-Immaculée au Canada (4 vol., Ottawa, 1976–1989) ; le Père du Keewatin : Mgr Ovide Charlebois, o.m.i., 1862–1933 (Montréal, 1962).— A. R. Greyeyes, « St. Michael’s Indian Residential School 1894–1926 : a study within a broader historical and ideological framework » (mémoire de m. serv. soc., Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1995). — R. [J. A.] Huel, « The Anderson amendments and the secularization of Saskatchewan public schools », SCHEC, Study sessions, 44 (1977) : 61–76.— Martin Lajeunesse, Directives missionnaires (The Pas, Manitoba, 1942).— « O. Charlebois à mon très révérend père général, 10 novembre 1901 », Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée (Paris), 40 (1902) : 48.— J.-M. Pénard, Mgr Charlebois (notes et souvenirs) (Montréal, 1937).— Marius Rossignol, « Mission de l’Île-à-la-Crosse », Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée (Rome), 56 (1922) : 49–59.— Arsène Turquetil, « Chez les Esquimaux du Keewatin », Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée (Rome), 50 (1912) : 441–444.— « Un journal catholique et français en Saskatchewan », les Cloches de Saint-Boniface (Saint-Boniface [Winnipeg]), 9 (1910) : 70.— « Vicariat du Keewatin : rapport du révérendissime vicaire des missions », Missions de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie Immaculée, 56 : 47.

Cite This Article

Raymond Huel, “CHARLEBOIS, OVIDE (baptisé William-Ovide),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed 28 février 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/charlebois_ovide_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/charlebois_ovide_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Huel |

| Title of Article: | CHARLEBOIS, OVIDE (baptisé William-Ovide) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | 28 février 2026 |