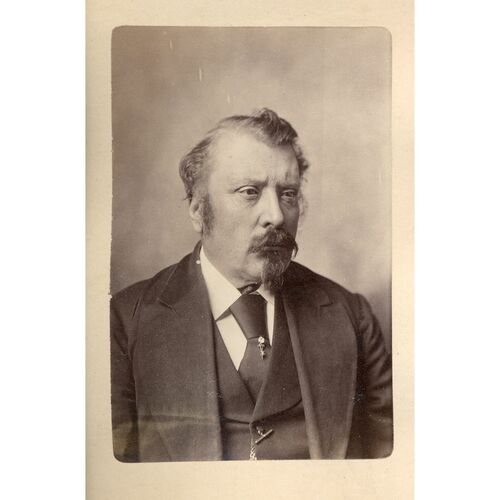

CREVIER, JOSEPH-ALEXANDRE, doctor and naturalist; b. 26 Feb. 1824 at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Lower Canada, son of Frédéric-François Crevier, dit Bellerive, a merchant, and Louise Rocheleau; m. in 1850, at Saint-Hyacinthe, Canada East, Zoé-Henriette Picard, dit Destroismaisons, and they had two sons and four daughters; d. 1 Jan. 1889 in Montreal, Que.

After studying with his uncle Édouard-Joseph Crevier, who later became vicar general of the diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe and founder of the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir, Joseph-Alexandre Crevier received a classical education at the Collège de Chambly, then at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. One of the first students of the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery, he received his licence to practise in 1849 and took up residence at Saint-Hyacinthe. From 1861 to 1872 he practised at Saint-Césaire, where he began a long series of scientific and popular publications. A tall man, with a broad brow and a bushy beard, whose timidity probably stemmed from a speech defect, Crevier was an eccentric, more at home in his laboratory, in his workshop (shaping wood and metal, or polishing the mirrors of his telescopes), and on geological expeditions in the field, than he was in society. In a somewhat slipshod manner, he wrote on most of the sciences, for his curiosity and erudition ranged from interest in the infinitely small to astronomy. Léon Provancher*, who chided him in a friendly way for spreading himself too thin, rated him highly and made him a member of his ephemeral Société d’histoire naturelle de Québec, and named two insects, the Meniscus and the Epyrhissa Crevieri, after Crevier, the discoverer of the Ichneumon Marianapolitensis, of the same genus. Crevier’s collection contained 1,443 specimens, mainly of Canadian minerals, fossils, molluscs, insects, and plants, as well as 656 microscopic preparations.

Crevier gained a reputation as a scientist through his articles in Le Naturaliste canadien and in newspapers before he went to Montreal in 1872. He was essentially a popularizer and a naturalist whose knowledge of taxonomy was not comparable to that of his compatriot, Augustin De Lisle*. Although in practising his art he displayed the researcher’s bent, he was self-taught and unaccustomed to the rigorous discipline of the scientific method. Hence his study on bufonine (a venom contained in the warts of the toad) whose toxicity he claimed to have demonstrated through subcutaneous injections that killed animals, is interesting but inconclusive. In 1866 he had published an Étude sur le choléra asiatique, which was as remarkable as it was debatable. Through microscopic examination of the faeces of cholera victims of the 1854 epidemic, he had discovered a micro-organism which was unknown to him. In four years of observing microzoa and microphytes collected in rivers, lakes, and ponds he found none resembling it. This confirmed his opinion that a bacterium was the agent of the cholera. His contemporaries, such as Jean-Gaspard Bibaud, attributed the contagion to unexplained emanations from plants or sick animals. A distinction was not always made between cholera morbus, an infinitely more serious disease, and relatively benign diarrhœic infections. Thus, the remarkable therapeutic efficacy of “Dr. Crevier’s celebrated anticholeric and antidyspeptic drops” made diagnosis of the disease and identification of its cause even more uncertain. But this modest country doctor’s assertion that a contagious disease was microbial in origin makes him one of the numerous obscure forerunners of Louis Pasteur.

In 1873 Crevier pointed out the presence of pathogenic animalculae in the stagnant waters of certain districts of Montreal, delivered a lecture on infusoria, and gave a course on “micrology” at the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery. He asserted in L’Album de la Minerve (Montreal) that he had discovered Bacterium variolare, the agent of smallpox (which is in fact a viral disease). It was soon raging in Montreal, and Crevier came out against compulsory vaccination. At the height of the 1875 epidemic, he even proposed that a league be formed to fight vaccination. Because the needles were often inserted in one arm after another without being re-sterilized, or were used with undiluted vaccine, he had reason to fear that vaccination would transmit smallpox and other serious diseases. He set little store by the contrary opinions of his colleagues, especially those who had founded the Montreal Medical Society and were publishing L’Union médicale du Canada. Its editor was Dr Jean-Philippe Rottot and the journal called to order doctors who resorted to publicity to ensure the sale of their own patent remedies.

Crevier’s lectures and articles on geology and the origin of the earth won him a reputation as a materialist and free-thinker; he joined the Institut Canadien of Montreal at the time of the last reverberations of the Joseph Guibord* affair. With journalist Auguste Achintre, he published an interesting monograph on the Île Sainte-Hélène, and, with Dr Guillaume-Sylvain de Bonald and some other Frenchmen, he taught at the Institut National des Beaux-Arts at Montreal directed by the mysterious Abbé Joseph Chabert*. Crevier was at the height of his fame when Elkanah Billings*, the palaeontologist to the Geological Survey of Canada, died in 1876. He was proposed as the successor to Billings, to whom he had supplied numerous fossils, including a new species of gastropod which he had called Pleurotomaria Crevieri. Despite exaggerated praise of Crevier by Chabert, who assumed he was as good as appointed, and the unanimous backing of the French-language press in Montreal, he did not obtain the post. Joseph Frederick Whiteaves*, a member of the survey who enjoyed the support not only of the English-language press but also of the director, Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn*, was chosen by the government.

The following year, the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery opened the chair of histology and microscopy to competition. Crevier drafted part of the discourse required for the examination, but as the date of the competition was not announced for a long time, he lost interest. His scientific activity slowed as publicity increased for his blood and hair restorer drops. He planned to present his remedy for cholera to the Académie Nationale de Médecine in Paris, and reworked his study on the question. Louis-Honoré Fréchette*, a friend of 25 years’ standing, urged him to communicate his work to the recently founded Royal Society of Canada. For some years before his death he was cultivating and studying the tuberculosis microbe. Two years after his death, a species of mollusc discovered by him was named Unio Provancheriana.

Fréchette aptly described Crevier: “He was like certain unschooled artists, who, forced to educate themselves by puzzling out even the most elementary methods involved in their work, sometimes achieve a masterpiece without ever attaining full mastery of their art.”

[The Crevier collection was willed to the Collège Saint-Laurent in Montreal, but was apparently lost because there is no mention of it in the chapter on the college’s museum in Sainte-Croix au Canada, 1847–1947 (Montréal, 1947).

In addition to articles published in La Minerve, Le Monde canadien (Montréal), Le National (Montréal), Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), L’Opinion publique, La Patrie, La Presse, L’Union médicale du Canada (Montréal), and other periodicals in the years from 1859 to 1885, Joseph-Alexandre Crevier published two pamphlets: Étude sur le choléra asiatique ([Saint-Césaire, Qué.], 1866); Le choléra, son historique, son origine, sa nature (Montréal, 1885). In collaboration with Auguste Achintre, he wrote: L’Île Ste. Hélène: passé, présent et avenir; géologie, paléontologie, flore et faune (Montréal, 1876). l.l.]

J.-G. Bibaud, Quelques considérations sur les causes et l’hygiène des maladies contagieuses et le choléra en particulier (Montréal, 1866). Joseph Chabert, Le premier Canadien nommé à l’éminente charge de paléontologiste de la Commission géologique du Canada (Montréal, 1877). L.-H. Fréchette, “Mémoires intimes; le docteur Crevier,” Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 10 nov. 1900: 434–35; 17 nov. 1900: 450; 24 nov. 1900: 467. Jacques Rousseau, “Le docteur J.-A. Crevier, médecin et naturaliste (1824–1889),” Assoc. canadienne-française pour l’avancement des sciences, Annales (Montréal), 6 (1940): 173–269.

Cite This Article

Léon Lortie, “CREVIER, JOSEPH-ALEXANDRE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/crevier_joseph_alexandre_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/crevier_joseph_alexandre_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Léon Lortie |

| Title of Article: | CREVIER, JOSEPH-ALEXANDRE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |

![[Joseph Alexandre Crevier, M.D.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Joseph Alexandre Crevier, M.D.] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.4581.jpg)