Source: Link

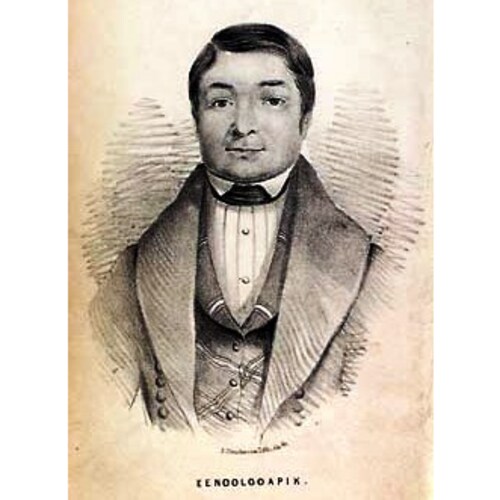

EENOOLOOAPIK (Bobbie), Inuit hunter, traveller, guide, and trader; probably b. c. 1820 at Qimisuk (Blacklead Island) in Tenudiakbeek (Cumberland Sound, N.W.T.), eldest son of his father’s marriage to Noogoonik; d. in the summer of 1847.

In Eenoolooapik’s youth his family and several others migrated along the coast of Baffin Island from Qimisuk to Cape Enderby, probably on the southeast coast of the Cumberland peninsula. There they met a party of British whalers with whom they travelled to Cape Searle, on the peninsula’s north shore. After learning about the whalers’ homeland Eenoolooapik conceived a desire to travel there. However, his father had taken a second wife from among the natives of Cape Searle, and Eenoolooapik was left as the main support of his mother. Several times he almost boarded a homeward-bound ship but each time his mother’s distress at being abandoned deterred him.

In September 1839 Eenoolooapik met the forceful whaling captain William Penny* at Durban Island. Penny had witnessed the decline of the Arctic fishery and agreed with a suggestion published by Captain James Clark Ross* that it was finished unless the whalers diversified and wintered in the north. The whalers, constantly on the lookout for new territory, had heard of a large bay, Tenudiakbeek, described by the Inuit as full of whales and supporting a numerous Inuit population. Penny felt that it might prove the perfect place for a settlement and save the fishery, but by 1839 he had failed three times to find it. When he learned that Eenoolooapik was a native of Tenudiakbeek, had a detailed knowledge of the local geography, and wished to visit Scotland, he determined to take him home to Britain. With Eenoolooapik’s help, Penny hoped to persuade the Royal Navy to explore the area.

Eenoolooapik embarked upon Penny’s ship Neptune and on the evening of 8 November arrived in Aberdeen. The next morning crowds gathered in the harbour to greet him and several days later he gave a display of his kayaking ability on the River Dee. Unfortunately he contracted pneumonia from these exertions and was, for several months, on the brink of death. The illness led to the curtailment of Penny’s plans to have him taught such skills as boat building.

Eenoolooapik was an intelligent, friendly man with a sense of humour and an ability to mimic others. These qualities were important, not only in his everyday life, but also on his visit to Scotland. They endeared him to locals who were so concerned about him that the Aberdeen papers carried information about his health. They also enabled him, upon his recovery, to behave like a born gentleman at the theatre, formal dinner parties, and two balls in honour of the queen’s wedding. An instance of his sense of humour which the Scots appreciated was reported in the Aberdeen Herald of 16 Nov. 1839: “One of the men at the Neptune’s boiling-house drew the outline caricature of a broad face, and said, ‘That is an Esquimaux.’ Bobbie immediately borrowed the pencil, and, drawing a very long face, with a long nose, said ‘That is an Englishman.”’

Penny dispatched the map he and Eenoolooapik had drawn to the navy but, although the Admiralty provided £20 to be spent on Eenoolooapik, it was not interested in an expedition to the area. On 1 April 1840, aboard the Bon Accord, Eenoolooapik left Scotland, sent off with many presents for himself and a china teacup and saucer for his mother. The Bon Accord spent the early summer whaling and then, with Eenoolooapik’s help, Penny took the ship into Tenudiakbeek. Believing it to be hitherto undiscovered, he named it Hogarth’s Sound after one of his financial backers. Later the sound was recognized as being the “Cumberland Gulf” visited by John Davis* in 1585.

Eenoolooapik left the whalers at his birthplace and near by rejoined his mother and siblings who had travelled overland from Cape Searle to meet him. Shortly after, he married Amitak and had a son, Angalook. To the surprise of the whalers his status was not greatly altered by his visit to a “civilized” country. Each year Penny returned, he traded baleen with him. Eenoolooapik died of consumption in the summer of 1847, before seeing the full effects of the information he had imparted to Penny. Five years after his death the first planned wintering of a whaling crew took place. Later, wintering over became standard practice and several whaling camps were based in Cumberland Sound until the final demise of Arctic whaling. Unknowingly Eenoolooapik had helped initiate the colonization of Baffin Island by non-Inuit.

Eenoolooapik was not the only traveller in his family. His brother Totocatapik was known among the Inuit as a great voyager and a sister, Kur-king, migrated to Igloolik. Another sister was the celebrated Tookoolito (Hannah), who visited England in 1853–55 and travelled extensively in the Arctic and the United States with explorer Charles Francis Hall*.

Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge, Eng.), ms 1424 (William and Margaret Penny, journal, 1857–58). Arctic whalers, icy seas: narratives of the Davis Strait whale fishery, ed. W. G. Ross (Toronto, 1985). “Davis Strait whale fishery,” Nautical Magazine (London and Glasgow), 9 (1840): 98–103. Alexander M’Donald, A narrative of some passages in the history of Eenoolooapik, a young Esquimaux . . . (Edinburgh, 1841). Aberdeen Herald and General Advertiser for the Counties of Aberdeen, Banff, and Kincardine (Aberdeen, Scot.), 1839–40. Aberdeen Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland, 1839–40. Alan Cooke and Clive Holland, The exploration of northern Canada, 500 to 1920: a chronology (Toronto, 1978). C. F. Hall, Life with the Esquimaux: the narrative of Captain Charles Francis Hall . . . from the 29th May, 1860, to the 13th September, 1862 . . . (2v., London, 1864). John Tillotson, Adventures in the ice: a comprehensive summary of Arctic exploration, discovery, and adventure . . . (London, [1869]). Richard Cull, “A description of three Esquimaux from Kinnooksook, Hogarth Sound, Cumberland Strait,” Ethnological Soc. of London, Journal, 4 (1856): 215–25. Clive Holland, “William Penny, 1809–92: Arctic whaling master,” Polar Record (Cambridge), 15 (1970): 25–43. P. C. Sutherland, “On the Esquimaux,” Ethnological Soc. of London, Journal, 4: 193–214.

Cite This Article

Susan Rowley, “EENOOLOOAPIK (Bobbie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eenoolooapik_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eenoolooapik_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Susan Rowley |

| Title of Article: | EENOOLOOAPIK (Bobbie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |