Source: Link

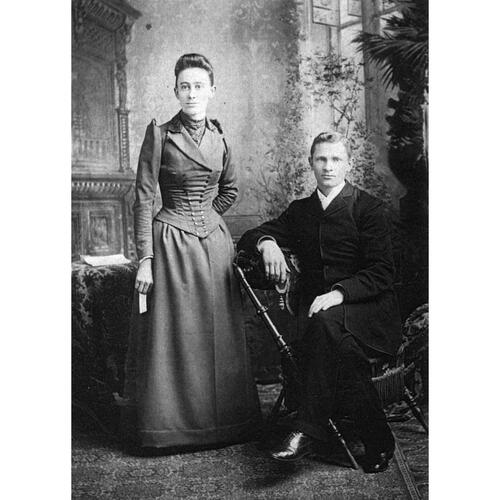

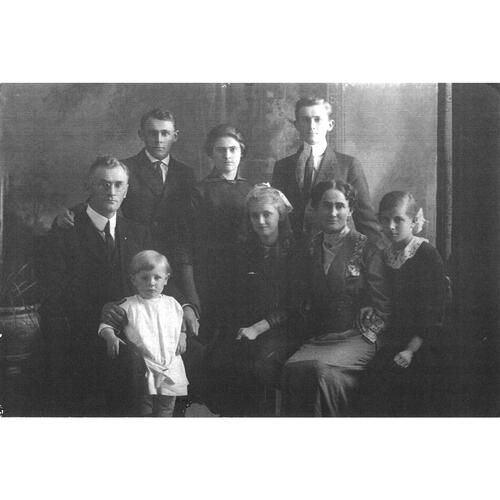

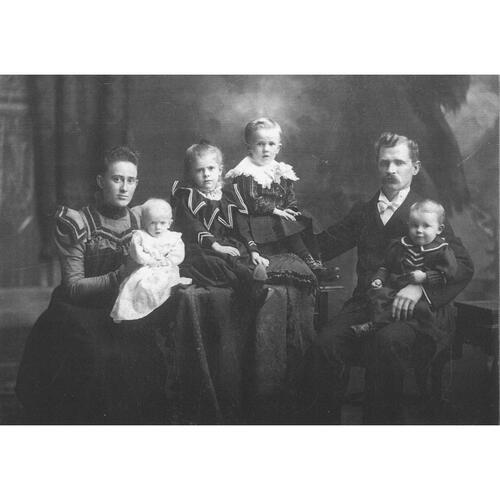

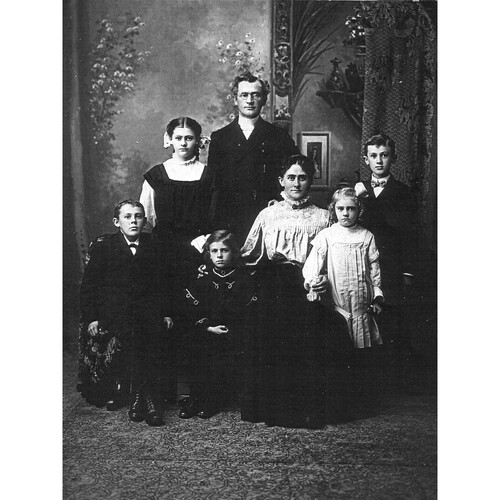

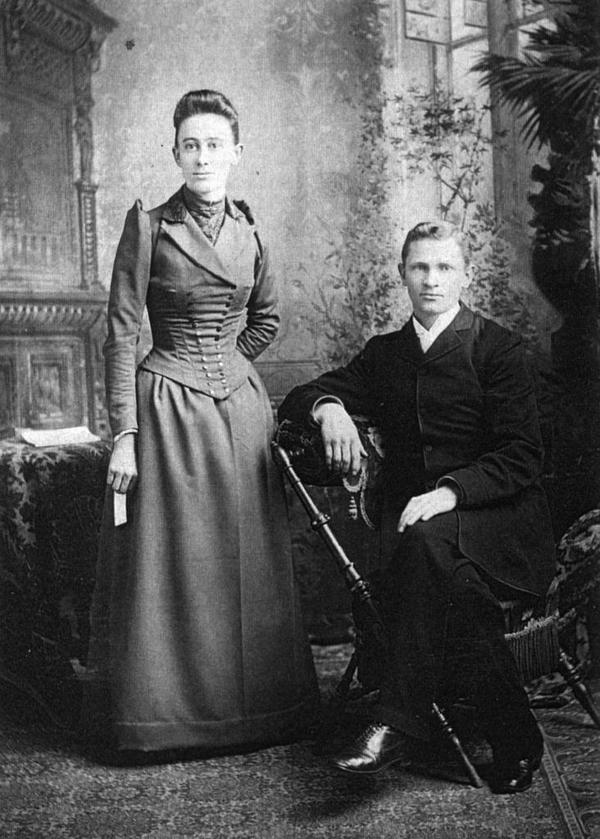

FREEMAN, BARNABAS (Barnard) CORTLAND (Courtland) (he was sometimes called Cortland and he usually signed B. C.), teacher, Methodist and United Church missionary and minister, and author; b. 30 July 1869 in Frontenac County, Ont., son of Barnabas Courtland Freeman and Sarah Lake; m. 28 Dec. 1892 Ida Lawson in Elginburg (Kingston), Ont., and they had three daughters and four sons; d. 17 Dec. 1935 at Cape Mudge Indian Reserve No.10, B.C.

Barnabas Freeman described himself as having been born of “poor but respectable” parents of loyalist background. The son of a Methodist preacher, he was shaped by religion during his early years, and at age 14 he experienced a religious awakening when he encountered a student preacher from Queen’s College, Kingston, who had come to supply the local Presbyterian congregation. After completing high school, Freeman earned a teacher’s certificate and spent five years teaching in Elginburg.

The rapid European settlement of the Canadian west at the end of the 19th century attracted many young Ontarian men in search of new opportunities. When a local minister encouraged him to turn his efforts to mission work, Freeman offered to take up a field in the Manitoba and North-West Conference of the Methodist Church. In 1892 he was at Red Deer Hill (Sask.). That summer a letter appeared in the Christian Guardian (Toronto) from the Reverend Ebenezer Robson of British Columbia requesting a missionary for the Haida at Skidegate on the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii). Freeman volunteered for the job despite knowing almost nothing of the people or the area. He was accepted and was hastily ordained a Methodist minister in Winnipeg while en route to Ontario to marry his fiancée.

Skidegate in 1893 was a Christianized village, and the work that had been accomplished by missionaries during the previous 20 years impressed Freeman. He shared the dominant view of Canada’s late-Victorian society that indigenous people needed to make a complete transformation from what he and others termed “savagery” to civilization. This perspective was reflected in the diverse activities he and his wife undertook during their decade at Skidegate: in addition to preaching the gospel, these tasks included running a day school and co-managing an indigenous joint-stock company that manufactured oil from dogfish. Freeman and his growing family learned the Haida language and won the affection of the people of Skidegate and the other villages among which they itinerated. This relationship is perhaps best evidenced by the fact that at least one Freeman child born at Skidegate was named by the Haida.

In 1903 Freeman was moved to Port Simpson (Lax Kw’alaams) on the mainland, and the following year to Port Essington. After 17 years among indigenous peoples, Freeman left mission work in 1910 for a pastorate in southern British Columbia so that his children could attend high school. In Cumberland, Revelstoke, Cranbrook, Coquitlam, and Vancouver he served Methodist congregations, which after 1925 belonged to the United Church of Canada [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon]. In 1920 he was honoured with the presidency of the British Columbia Conference of the Methodist Church. His retirement in 1933 was short-lived; later that year he volunteered to be a missionary at Cape Mudge Indian Reserve No.10, off Vancouver Island. He died there unexpectedly in 1935 of a heart attack.

An avid writer, Freeman penned an impressive number of poems during his career, about 20 of which were published in the Christian Guardian and the New Outlook (which resulted from the merger of the Christian Guardian with two other denominational journals in 1925) as well as in other church periodicals. His poetry reveals a contemplative man who found inspiration – and divinity – in nature. In “Pagan” (published in New Outlook on 24 April 1926 under the title “Wild acreage”) Freeman wrote: “O you theologians, come and look! For God is laughing in this running brook.” “Sense of the infinite” (1925), “Esoteric” (n.d.), and “Wood-spell” (1927) are among his many poems that attempt to explore the intangible. Christian themes such as love, faith, and sin are examined in the context of individual salvation and as a means of social criticism. Though often playful, Freeman’s poetry expresses deep concern about the tumultuous developments of the first decades of the 20th century in Canada: the horrible cost of war, the smug materialism of the 1920s, and the exploitation of the common worker during the Great War and the Great Depression are explored in poems such as “War” (1932), “The wrecking of the Wesley Church” (n.d.), and “Song of the relief man” (1933).

Freeman’s non-fiction and prose demonstrate his extensive contact with the indigenous cultures of coastal British Columbia. His missionary articles, written for church periodicals and, later, his short stories demonstrate that these cultures captured his imagination and that he had developed a genuine concern for the well-being of indigenous peoples in a rapidly changing society. His pamphlet The Indians of Queen Charlotte Islands, published in Toronto around 1904, documents his knowledge of the history and cultural practices of the Haida. He advocated a “home” in the Skidegate mission that would enable parents to leave their children under the care of missionary instructors during the fishing and hunting seasons, and he highlighted its advantages over distant residential schools [see Allen Patrick Willie]. He lamented that “after a number of years [residential-school students] return to their people with their sympathies utterly alienated from the old life, and unprepared for taking it up again among them.” Yet despite his particular interest in indigenous people, his view of them changed little. In his writings, aboriginal people appear as a noble race plagued both by their own superstitions and by the evils of contact with Euro-Canadian society.

Freeman wrote a play about Thomas Crosby*, the well-known Methodist missionary who had preceded him at Port Simpson, entitled “Thomas Crosby, a pageant.” It was not published, though it may have been performed by supporters of Methodist missionaries in Ontario. The play celebrates Crosby’s missionary work, but interestingly, in the concluding scenes, the character “Indian Manhood” criticizes white society and defends the value of indigenous cultures. He also began writing a novel that was never finished, “Gedanst,” about a high-ranking Haida youth of that name who converted to Christianity, after which he carried the name Amos Russ. The overarching message in Freeman’s works is clear: bringing Christ’s gospel to indigenous people would redeem both them and the dominant society. Indeed, he felt that his mission work contributed to this end. In 1930, in a personal letter, he wrote that he greatly missed the “closeness of touch” and the wide range of responsibilities he had known among indigenous people, which made his earlier work seem nearer to true ministry.

Barnabas Cortland Freeman helped to ensure the growth and vitality of the Methodist and United churches in British Columbia over more than four decades. His work was shaped by concern about the social effects of the developments that were transforming Canadian society. He believed that the emerging social order should forget neither what he described as humanity’s “higher reachings” nor the Christian call to battle social injustices.

Barnabas Cortland Freeman is the author of “Mission work on Queen Charlotte Islands,” Methodist Magazine and Rev. (Toronto), 56 (July–December 1902): 202–13.

UCC, B.C. Conference Arch. (Vancouver), Arch. Reference Coll., Biographical files (Freeman, B. C.), box 2082; B. C. Freeman fonds, boxes 569–70. Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ont.), 17 Jan. 1936. Brant Gibbard, “Brant Gibbard’s genealogy pages”: www.bgibbard.ca/genealogy (consulted 28 July 2015). Methodist Church, Missionary Soc., Annual report (Toronto), 1893–1906. F. C. Stephenson, “The Rev. B. C. Freeman: a pioneer missionary in British Columbia,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev. (Toronto), June 1936: 16–17.

Cite This Article

Nicholas May, “FREEMAN, BARNABAS COURTLAND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/freeman_barnabas_cortland_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/freeman_barnabas_cortland_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nicholas May |

| Title of Article: | FREEMAN, BARNABAS COURTLAND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | February 9, 2026 |