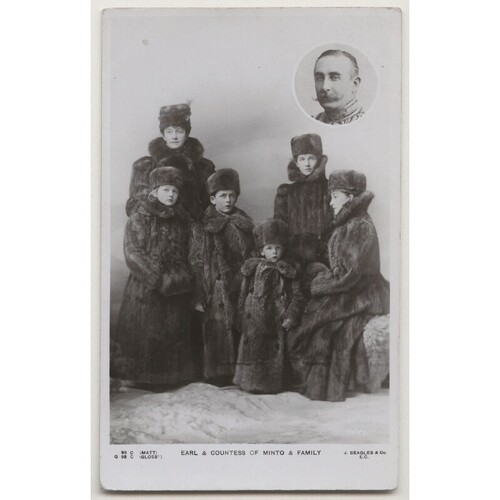

GREY, Mary Caroline (elliot, Viscountess MELGUND and Countess of MINTO), vicereine, social reformer, and author; b. 13 Nov. 1858 at Windsor Castle, England, youngest daughter of Charles Grey and Caroline Eliza Farquhar; m. 28 July 1883 Gilbert John Murray-Kynynmound Elliot*, Viscount Melgund, in London, England, and they had three daughters and two sons; d. 14 July 1940 near Godalming, England, and was buried in the Church of Scotland graveyard at Minto, Scotland.

Mary Caroline Grey was raised at the Court of St James’s in Windsor, England. Her father, a general in the army, served as equerry to Queen Victoria and as private secretary to Prince Albert and, after Albert’s death, to the queen. When her father died in 1870, Mary moved to St James’s Palace, London, with her mother, to whom the queen had granted an apartment there. A Hanoverian governess supervised Mary’s education in German and French, an education that included instruction in religion as well as in the social arts of dancing and singing. Her linguistic training was reinforced by her mother, who rarely spoke to her in English.

The Greys had a long-standing association with North America. Mary’s paternal great-grandfather, who became the 1st Earl Grey in 1806, had commanded a British brigade during the American rebellion. Her father (the second son of the 2nd Earl Grey) was lieutenant-colonel of the 71st Foot at the time of the uprising in the Canadas [see William Lyon Mackenzie*; Louis-Joseph Papineau*] and later assisted Lord Durham [Lambton*], the governor-in-chief of British North America. Mary herself would serve two terms in Canada.

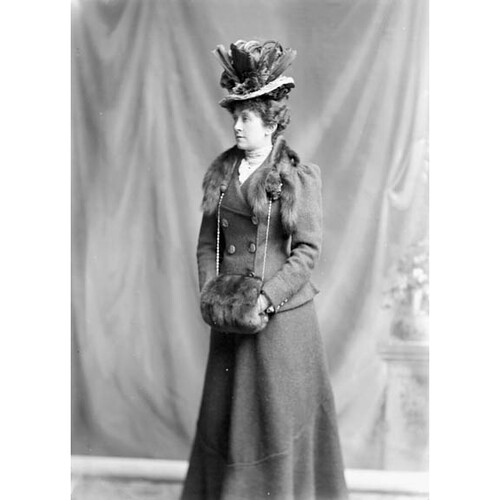

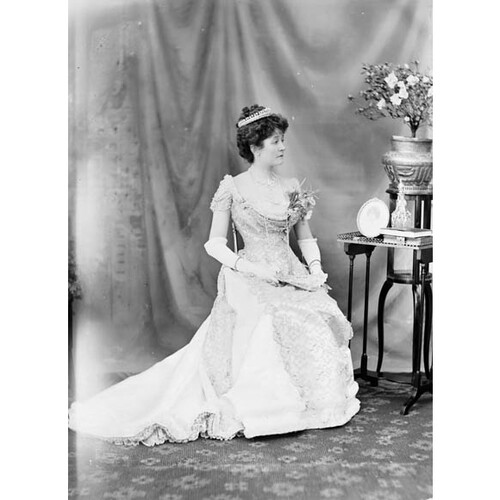

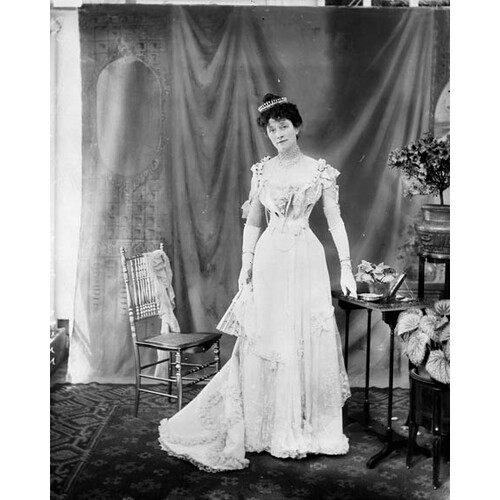

Mary said that she “longed” to be a boy in her youth and to join in the games and activities of her young male relatives. Tall, slight, athletic, and energetic, she relished such sports as skating and bicycling. She was known for her grace, style, charm, and exuberance, qualities that were frequently praised in London’s fashionable Vanity Fair. She was also an intelligent, articulate, and judicious person who participated in the Souls, a small coterie of British intellectuals and politicians who began to meet in the mid 1880s to discuss issues of the day. Another member of the group, Margot Asquith, Countess of Oxford and Asquith, would include Mary among the 15 women “of influence and achievement” invited to contribute to her volume Myself when young (1938).

In 1883 Mary married Lord Melgund, a family friend 13 years her senior, in a union that bestowed no great financial benefit on either party. Shortly before their wedding Melgund had agreed to become military secretary to Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], the recently appointed governor general of Canada. Although Lady Melgund was reluctant to exchange the Court of St James’s for Rideau Hall in Ottawa, she greatly enjoyed her two years’ residence in Canada, the birthplace of her eldest child. In 1898 she was more than ready to return as the consort of the governor general, an appointment that her court influence had helped her husband, now the Earl of Minto, to secure. The Mintos succeeded Lord and Lady Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon; Marjoribanks], whose somewhat chaotic and democratic approach to official activities, frowned upon by the queen, they now endeavoured to reverse. Their attempts to enforce punctuality, curtail entertainment, and purge guest lists (the latter efforts no doubt encouraged by a declining income) initially cast them as stiff proconsuls out of touch with an increasingly egalitarian society. Soon, however, the couple placed their own, less formal mark on the viceregal office.

Although Lady Minto enjoyed regaling her court friends with tales of the Aberdeens’ Canadian antics, she continued her predecessor’s work by assuming the honorary presidency of Lady Aberdeen’s two chief institutional legacies: the National Council of Women of Canada and the Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada. Her role in the NCWC was largely nominal, but she took an active interest in the work of the VON. Impressed by the need for better public-health facilities, she created a fund of some $100,000 to extend the VON’s cottage hospitals in settlements of more than 2,000 people in the northwest and elsewhere, a project she promoted as a memorial to Queen Victoria. Eventually 43 hospitals were established under the scheme. At the Ottawa Maternity Hospital [see Ella Hobday Webster*] a Lady Minto wing, opened in 1900, recognized her interest in nursing. She furthered Lady Aberdeen’s work as well by becoming president of the Aberdeen Association, which sought to distribute reading materials to isolated settlers. She also used her influence to beautify Ottawa’s streets, sponsored competitions and offered prizes for the best care and ornamentation of lawns and gardens, and in 1903 became an honorary president of the Canadian League for Civic Improvement.

Lady Minto shared her husband’s interest in preserving Canada’s heritage, such as the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City, the fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, and the country’s archival records. It was at her suggestion that the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa was founded in 1898, with one of its objectives the conservation of historical documents and artefacts. Like her husband, she promoted sports (she was an enthusiastic hockey fan) and especially encouraged figure skating, in which she excelled. She recalled this activity as her “keenest enjoyment” in Canada, though she broke her leg on rotten ice just before she left in 1904, an injury that would plague her for the rest of her life. As a lasting monument to her passion, she founded with her husband the Minto Skating Club to foster competitive figure skating. In her final years her most vivid recollections of Canada seem to have been of “the titanic majesty” of its natural environment and her various adventures in the wild: visiting the Yukon just after the gold rush had peaked, camping in the northwest in very basic conditions and uncertain weather, canoeing in Quebec on Lac Saint-Jean and the Saguenay, and shooting the Little Chaudière Rapids on the Ottawa River.

Skilled at social diplomacy, with a good memory for faces and fluency in French, she often compensated for her husband’s brittle sensibilities. In 1901, for example, she accompanied the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall on their Canadian tour to paper over her husband’s qualms as to whether he, as the king’s representative, or the duke should take precedence in public. The New York Times described her as one of Canada’s most popular viceregal spouses, applauding her permissive, “American”-style family life, which saw her devoting personal time to her children’s education and entertainment. She was well liked in the United States, where she frequently visited friends, such as the financier John Pierpont Morgan, President William McKinley, and governor and then president Theodore Roosevelt; she also received American visitors at Rideau Hall.

Not all her activities drew praise. In February 1902 her sponsorship of the Canadian South African Memorial Association, set up to mark and care for the graves of the Canadians who had died in the South African War, triggered an acrimonious and protracted public dispute with the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire. Not only had the IODE launched a similar project, but Lady Minto had agreed to be the organization’s honorary president as well as honorary treasurer of its war-graves fund [see Margaret Smith Polson*]. And while a “sporting set” enjoyed the Mintos’ skating and tobogganing parties, and close friends appreciated the family’s carefully staged theatricals at Rideau Hall, the viceregal entourage drew criticism for occasional indiscreet public pronouncements and for somewhat raffish behaviour, including a propensity for nude bathing.

The Mintos left Ottawa in 1904, at which time Lord Minto was succeeded as governor general by Mary’s brother Albert Henry George Grey*, 4th Earl Grey. During their sojourn in Canada the couple had developed an attachment to the country, revelling in “its people, its sunshine, its mountains and its mighty rivers,” as Mary would later write. Intoxicated by its future promise, they considered settling in the west and building a house at the foothills of the Rockies in sight of the Bow River. Any chance of fulfilling this dream ended in 1905 after they returned to Scotland and Lord Minto received his coveted appointment as viceroy of India, a promotion he attributed partly to Lady Minto’s “good work in Canada.” Mary would describe the next years of their lives in her book India, Minto and Morley, 1905–1910 (1934), which drew heavily on her private diary. While in the subcontinent she established Lady Minto’s Indian Nursing Association to provide medical care to Europeans and solicited funds to support it. For her charitable work in Canada she had been appointed a lady of grace in the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England in 1904, and her activities in India would bring her promotion as a lady of justice in 1911.

After the couple returned home in 1910, careless estate management, including excessive personal expenditure, strained the family’s limited resources. The situation was relieved in 1911 when Queen Mary chose the countess to be a lady of the bedchamber (a position well suited to her personality and social skills) and she began to receive annual emoluments from the royal household. But following Lord Minto’s death in 1914 the family’s difficulties were exacerbated by the obligations of the succession and the financial constraints of the Great War. Rumours in 1915 that Lady Minto’s close friendship with Lord Kitchener might lead to matrimony were cut short when the ship in which he was travelling struck a German mine and he perished. Altogether the war exacted a heavy toll, above all in the deaths in action of her son-in-law Lord Charles George Francis Mercer-Nairne (Lord Lansdowne’s second son) in 1914 and her younger son, Gavin William Esmond Elliot, three years later.

The countess retained an interest in Canada. In 1923 she gave the idea of establishing a Canadian history society in London “whole-hearted support,” in the words of Arthur George Doughty, the dominion archivist, and she became the organization’s vice-president. By this time she had persuaded John Buchan to take on the biography of her husband, an account she herself had first tried to write. She gave him, he wrote, “such constant and invaluable help that in a real sense the book is her own.”

Lady Minto remained involved in nursing after her return from India. From 1911 to 1937 she served on the board of the Territorial Force (later Territorial Army) Nursing Service. She continued to attend Queen Mary until the last years of her life, being appointed in 1936 an extra lady of the bedchamber. That the wartime London Times devoted almost a full-length column to her death in 1940 underscores her public standing 26 years after her husband died.

Mary Caroline Grey, Countess of Minto, is the compiler of India, Minto and Morley, 1905–1910 (London, 1934).

National Library of Scot. (Edinburgh), mss 12365–803 (4th Earl of Minto, papers). “Lord et Lady Minto,” La Patrie, 18 nov. 1904: 4. New York Times, 12 July 1903. Ottawa Evening Journal, 1898–1904. Times (London), 16, 17, 18, 19 July 1940. John Buchan, Lord Minto: a memoir (London, 1924). Carman Miller, The Canadian career of the fourth Earl of Minto: the education of a viceroy (Waterloo, Ont., 1980). Myself when young: by the famous women of to-day, ed. [Margot Asquith], Countess of Oxford and Asquith (London, 1938). Types of Canadian women …, ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “GREY, MARY CAROLINE (Elliot, Viscountess MELGUND and Countess of MINTO),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grey_mary_caroline_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grey_mary_caroline_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | GREY, MARY CAROLINE (Elliot, Viscountess MELGUND and Countess of MINTO) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |