Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

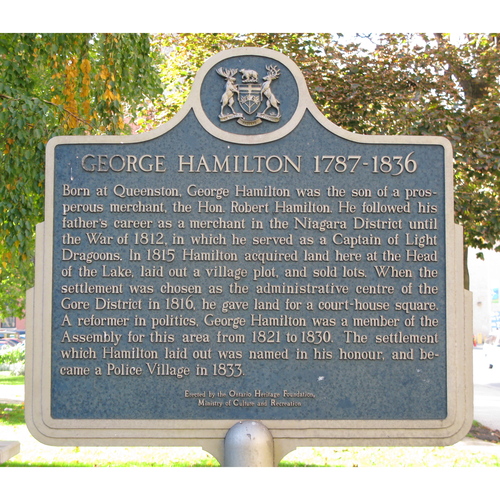

HAMILTON, GEORGE, businessman, militia officer, office holder, and politician; b. October 1788 in Queenston (Ont.), son of Robert Hamilton* and Catherine Robertson, née Askin; m. 2 Aug. 1811, in York (Toronto), Maria (Mary) Lavinia Jarvis, daughter of William Jarvis* and Hannah Peters, and they had three sons and five daughters; d. 20 Feb. 1836 at his residence in Hamilton, Upper Canada.

George Hamilton received some schooling locally before his father escorted him to Scotland in 1795 for further education. After their father’s death in 1809, George and his brother Alexander inherited his various enterprises. Between 1809 and 1812 they mismanaged business affairs and clashed with their brothers and also with their influential kin who were trustees of the estate. During the War of 1812 George, who had received a commission in the militia in 1808, held the rank of captain in Thomas Merritt’s Niagara Light Dragoons. He took part in the capture of Detroit and the battle of Queenston Heights in 1812 and the battle of Lundy’s Lane in 1814.

The disruption of trade and immigration that accompanied the war exacerbated a decline in the Hamiltons’ business that had been evident even at the time of Robert Hamilton’s death. When peace was restored George set out to re-establish himself. He shifted his interest to the Head of the Lake (the vicinity of present-day Hamilton Harbour). In July 1815 he purchased 257 acres in Barton Township from James Durand* for £1,750. Within a year he reached an agreement with a neighbouring landowner Nathaniel Hughson to develop a town site there. They empowered Durand, the local assemblyman, to act as their agent in the sale of town lots. This initiative coincided with the government’s decision in 1816 to erect a new district in the area and to designate Hamilton’s site its capital. The political and business dealings behind the selection of the site are obscure. They had, no doubt, something to do with Durand’s influence in the House of Assembly and Hamilton’s connections. To accommodate a court-house and jail, the central public buildings in a district capital, Hamilton ceded two blocks of land, of two acres each, to the crown. The town site itself, modelled on the popular grid pattern of most North American frontier towns, was carved into readily surveyed parcels. In 1828–29, when the original lots had been sold, Hamilton would add more. By the 1830s the village of Hamilton (incorporated in 1833) contained rivals who would defeat George’s bid to locate the market on his lands; instead he was forced to settle for a more modest hay market.

George Hamilton was drawn into politics through his association with Robert Gourlay* in the late 1810s. He may have become involved in the agitation partly because of a personal setback with a milling venture on the Grand River; the operation seems to have failed by 1819. It is possible that the regional grievances of the Niagara peninsula, especially the unsettled claims. for war losses (Hamilton’s among them), contributed to his dissatisfaction, and his Presbyterian background perhaps played a role as well. Moreover, he undoubtedly perceived the clergy and crown reserves as impediments to settlement and therefore to the advancement of his own interest. In 1818 he and William Johnson Kerr carried Gourlayite resolutions to Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland*, who refused to receive them. Hamilton and Kerr reacted by running, successfully, for the assembly in the election of 1820. Hamilton was one of the representatives for the riding of Wentworth in the eighth (1821–24), ninth (1825–28), and tenth (1829–30) parliaments. These years coincided with the rise of the village of Hamilton and mark the zenith of George Hamilton’s influence and fortunes.

From his initial appearance in the assembly in February 1821 until March 1828, Hamilton aligned himself with reformers. At first, he worked closely with John Willson*, his fellow member from Wentworth. Following Willson’s election as speaker in 1825, Hamilton associated with John Rolph*. Resentful of the Maitland administration’s treatment of Gourlayites such as Richard Beasley, he constantly needled Attorney General John Beverley Robinson*. Reform positions drew his support: he favoured the seating of Barnabas Bidwell*, criticized the state of public accounts, and advocated the assertion of the assembly’s prerogatives. He complained about retrenchment which, he believed, threatened internal development. Rank and hierarchy were little appreciated by this merchant of Presbyterian background. He naturally opposed the various measures and practices which gave the Church of England its favoured status; indeed, his religious views were particularly liberal.

The tie between a moderate reformer such as Hamilton and commercial interest was evident in his impatience with the slow rate of settlement and the depressed state of public works. A series of resolutions in 1823, moved by William Warren Baldwin and seconded by Hamilton, criticized the lack of immigrants, proposed the elimination of the reserves, urged the location of new settlers close to roads and mills, and recommended the granting of entire townships to men of capital able to develop mills and forges. With his mercantile background, Hamilton was wary of taxes on trade and opposed duties on salt and whisky (to finance the Welland Canal). He maintained that the more orderly keeping of public accounts could ensure the financing of improvements, presumably by reducing the fees paid to the colony’s officials. As late as March 1829, he returned to the topic of immigration and, with Willson, introduced a bill to encourage it.

During the 1820s, George sponsored several measures of express benefit to the village of Hamilton. Beginning in 1823, he pressed the government to cut a canal linking Lake Ontario with Burlington Bay (Hamilton Harbour). Once the work was underway, problems between the canal’s commissioners and their contractor, James Gordon Strobridge*, took some of the lustre off an important local improvement despite its successful completion. From 1825 to 1827, Hamilton worked to secure public funding for a new court-house and jail at Hamilton, an undertaking which stirred up resentment from rival communities [see Peter Desjardins*] and brought critical petitions against it. George was forced to defend Hamilton’s status as capital of the Gore District. In March 1828 he moved assembly acceptance of a petition requesting a grant of £2,000 for work on the stalled Desjardins Canal project, but reformers Peter Perry* and Marshall Spring Bidwell* moved, successfully, to postpone a decision.

In 1829 Hamilton was badly squeezed between his constituency and the reformers by the “Hamilton Outrage” – the hanging in effigy of the lieutenant governor over his refusal to release imprisoned journalist Francis Collins* [see Strobridge]. As events got out of hand, Allan Napier MacNab*, a Hamilton lawyer, was jailed for contempt of the assembly. He had refused to testify before a house committee examining the outrage. George tried to chart a moderate course, but more often than not, this tack placed him and Willson at odds with other reformers eager to pursue the issue for all it was worth. Another local affair which caused him similar problems was a complaint by George Rolph (John’s brother), clerk of the peace, against Gore District magistrates for wrongful dismissal. Because it reflected critically upon Hamilton’s associates among the Wentworth gentry, he refused to support it. He recoiled from a partisan exploitation of reform issues embarrassing to the Gore District and his own political survival, but, in spite of the charge by some historians that such trimming indicated a pro-government stance, Hamilton’s fundamental inclinations were reform-oriented. In March 1829, at the same time as the events surrounding the outrage were unfolding, Hamilton voted for resolutions designed to assert the assembly’s claim to control over finances whereas Willson voted against them.

Controversy over his role as a town-site promoter and failure to campaign aggressively cost Hamilton his seat in the election of 1830. He finished last in a four-way fight: Willson topped the polls and MacNab edged out Durand. MacNab was a political newcomer who had advanced himself swiftly because of his role in the outrage and his support for the interests of Hamilton and Dundas. Concurrent with MacNab’s rapid rise was Hamilton’s embarrassment over a shortfall in his accounts as district treasurer. Although he made up the deficiency personally, his stature may have been damaged by its disclosure and the outlay of funds may have hampered his ability to finance his re-election. He remained in public life but without a platform. He could scarcely dispute the affable and younger MacNab’s pursuit of improvements to local transportation and he had found, as a result of his loss in the 1830 election, that he could not associate with radical reformism. Indeed, in 1831 he spoke against William Lyon Mackenzie* at a local political meeting. The following year he chaired a hastily organized board of health formed to handle the cholera epidemic. In 1834 he stood, unsuccessfully, against MacNab for the newly established seat for Hamilton. Still a relatively esteemed member of the Burlington Bay gentry, Hamilton had, none the less, become unelectable.

George Hamilton took up politics to enhance his personal fortune and to shape society in ways conducive to commercial success. In his espousal of causes and principles harmonious with commerce and land speculation he was no different from the “family compact.” Yet his adherence to reform principles is a reminder that the colonial élite of which he was part was not at one on political matters; consideration of the province’s future invited conflict over the proper social ends of policy and over the correct management of resources to achieve those ends. Hamilton combined support for the crown with advocacy of a broadly latitudinarian constitution dominated by the assembly. This combination would be, in effect, the basis for the political accord reached in the 1840s and 1850s. Along with other moderates of the 1820s, the privileged North American Scot had hit upon the formula of increased immigration, religious toleration, improvements to transportation, and a collaboration of business and government that has often flourished since as policy in Canadian politics.

AO, RG 1, A-I-6: 4820–21, 8728–31; RG 22, ser.155. PAC, MG 24, D45, 7, Thomas Clarke to James Hamilton, 10 Oct. 1821; RG 5, A1: 22753–55. Private arch., Miss Ann MacIntosh Duff (Toronto), Family geneal. docs. Wentworth Land Registry Office (Hamilton, Ont.), Barton Township, deeds, vol.A (1816–29) (mfm. at AO). U.C., House of Assembly, Journal, 1821–30; 1826–27, app.R. Kingston Chronicle, 15 Dec. 1826, 16 Feb. 1827. Upper Canada Herald, 1, 15, 29 March, 24 May 1825. Armstrong, Handbook of Upper Canadian chronology (1985). DHB. D. R. Beer, Sir Allan Napier MacNab (Hamilton, 1984). Darroch Milani, Robert Gourlay, gadfly. J. C. Weaver, Hamilton: an illustrated history (Toronto, 1982), 16–17. B. G. Wilson, Enterprises of Robert Hamilton.

Cite This Article

John C. Weaver, “HAMILTON, GEORGE, (1788-1836),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_george_1788_1836_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_george_1788_1836_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | John C. Weaver |

| Title of Article: | HAMILTON, GEORGE, (1788-1836) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |