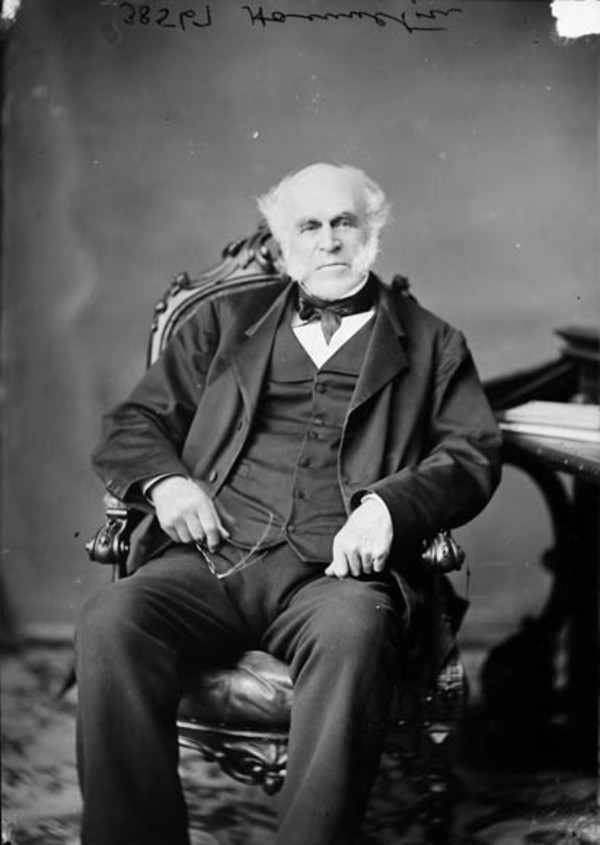

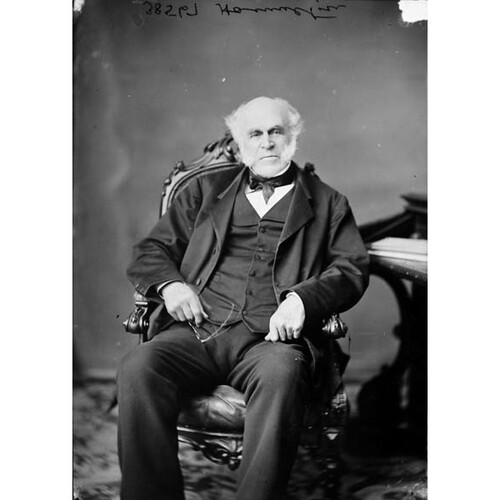

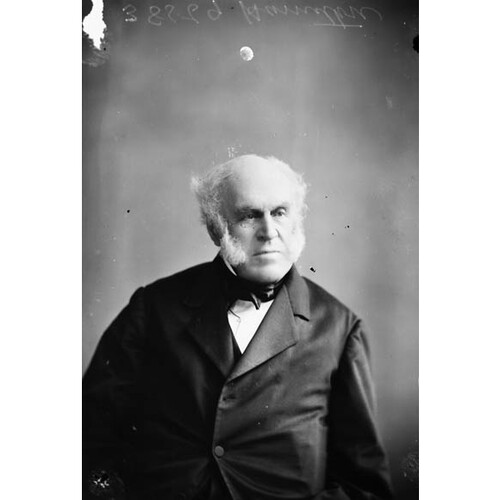

HAMILTON, JOHN, businessman and politician; b. 1802 at Queenston, Upper Canada, youngest son of Robert Hamilton* and Mary Herkimer, widow of Neil McLean*; d. 10 Oct. 1882 at Kingston, Ont.

John Hamilton was born into a wealthy and influential family. He received a classical education at Queenston and Edinburgh, Scotland, before working as a clerk from 1820 to 1824 for Desrivières and Blackwood, wholesale merchants in Montreal. John’s father had died in 1809, but because of his youth and the complicated nature of the will, he did not receive his share of the estate until 1824. The final settlement, although not totally satisfactory to John, did enable him and his stepbrother Robert to found the Queenston Steamboat Company.

The brothers purchased a used steamboat, the Frontenac, from Henry Gildersleeve* for about £1,500 in January 1825 to add to a new but smaller steamer which they had built, the Queenston. The Frontenac sailed between Kingston and Niagara, stopping at York (Toronto) on its return, and the Queenston sailed between Prescott and Niagara, with stops at Kingston and York. Robert left the partnership probably in the late 1820s. John Hamilton repeatedly utilized technical innovations to succeed in the financially hazardous and extremely competitive inland shipping business. In 1830–31 he had the Great Britain, a new model steamer, built at Prescott at a cost of over £20,000. He also owned the Lord Sydenham, the first large steamer, and the Passport, the first iron steamer, to run the Lachine rapids. A shrewd manager, he generally owned only two or three steamboats and leased others, which allowed him to keep his overhead costs down and to react more quickly than many of his competitors to sharp fluctuations in the economy. He avoided competitive wars and instead sought rate agreements which guaranteed all operators a profitable return.

In the early 1840s, partly because of the reckless competitive practices of his Lake Ontario rivals, Donald Bethune* and Hugh Richardson*, Hamilton temporarily stopped the Lake Ontario runs and concentrated on the St Lawrence trade. Transferring his home and business from Queenston to Kingston, he began a forwarding business between that place and Montreal. By 1850, Richardson was bankrupt and Bethune was floundering. That year, associated with the large forwarding firms of Macpherson and Crane, and Hooker and Holton, Hamilton re-entered the lake business. In 1857, as the main proprietor of the Canadian Lake and River Line, he operated most of Bethune’s old boats which he had probably purchased after Bethune’s bankruptcy. The “debilitating” competition of the Grand Trunk Railway forced Hamilton into a brief retirement in 1862 but he recommenced operations in 1865 and by 1868 he was the Kingston manager for the Canadian Navigation Company. A multipartnership, like its predecessors in the 1840s and 1850s, the company was also called the Royal Mail Line.

Hamilton was less successful in his career as a banker. After a period as vice-president of the Commercial Bank of the Midland District, he succeeded John Macaulay* as its president in 1847, a position he held until the early 1860s. Hamilton used his position with the bank to strengthen his steamboat business. He persuaded the bank to end its business with Donald Bethune and in 1847 it initiated proceedings against him to recover an overdue loan. In areas separate from his interest in shipping, Hamilton’s administration was extremely lax. By June 1859, for example, the bank had allowed the Detroit and Milwaukee and the Great Western railway companies to borrow amounts totalling $942,672, more than the companies could repay. Decisions such as these led to the demise of the bank.

Although never his major interest, Hamilton’s political career was exceptionally long. In 1831 he accepted an “unexpected . . . [and] undesired” appointment to the Legislative Council of Upper Canada. His initial reluctance soon disappeared and he sat in the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada from 1841 to 1867 and served in the Senate from 1867 until his death. His 51-year career as a Conservative councillor and senator was marked by dependable, rather than innovative, legislative service.

His involvement with Queen’s College at Kingston was of a more positive nature. Despite a belief that Canada West lacked the money to support a separate Presbyterian institution and that only one “United College” giving instruction in every area but divinity should be created, Hamilton was a co-founder of Queen’s and provided respectability and solidity in its troubled early years. His business contacts and his political position were used to the advantage of the college. An ardent Presbyterian, he none the less agreed with William Morris*, co-founder and chairman of the board of trustees, that the laity, not the clergy, should control the board. When Morris resigned late in 1842, Hamilton, characterized by a Queen’s historian as a “competent” layman, became chairman and remained so until he died.

By the mid 1870s, Hamilton, “one of those thoroughly aristocratic men,” was a patriarchal figure in the Kingston area. He had been an incorporator of the Wolfe Island, Kingston and Toronto Railroad Company in 1846 and the Union Forwarding and Railway Company in 1859 as well as a director of the Kingston Fire and Marine Insurance Company and the Life Association of Scotland. For a short period of time he operated a stage-coach line and during most of his life, like many of his contemporaries, he speculated in land. He was at one time president of the Kingston St Andrew’s Society. Some time before 1830 he had married Frances Pasia (d. 1873), sister of David Lewis Macpherson*, a Conservative ally of John A. Macdonald*, and one of his 11 children married a son of William Henry Draper*.

AO, MU 1143. MTL, James Van Cleve, “Reminiscences of early sailing vessels and steam boats on Lake Ontario” (typescript). PAC, MG 24, D24; I26, 4–6; 65. QUA, William Morris papers, 1–2; Queen’s Univ. letters, Hugh Allan to Hamilton, 11 April 1854; Hamilton to Allan, 24 April 1854; Hamilton to McIver, 16 June 1854; James Sutherland papers. Canadian Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Rev. (Toronto), 1 (April–September 1857): 58, 327–28; 3 (April–December 1858): 239. Commercial Bank of Canada v. Great Western Railway Co. (1862–64), 22 U.C.Q.B. 233. Counter v. Hamilton (1839–40), 6 U.C.Q.B. (O. S.) 612. Great Western Railway Co. v. Commercial Bank of Canada (1862–65), 2 U.C.E. & A. 285. Henderson et al. v. Graves (1862–65), 2 U.C.E. & A. 9. Holcomb v. Hamilton (1862–65), 2 U.C.E. & A. 230. McDonell et al. v. Bank of Upper Canada (1850–51), 7 U.C.Q.B. 252. British Colonist (Toronto), 4 May 1842. Chronicle & Gazette, 20 May 1837. Daily British Whig, 11 Oct. 1882. Globe, 12 Oct. 1882. Hamilton Spectator, 15 Oct. 1851. Leader, 26 March 1857. Queen’s College Journal (Kingston, Ont.), 25 Oct. 1882. Toronto Daily Mail, 9 Dec. 1882. The Canadian mercantile almanack . . . (Niagara, [Ont.], and Toronto), 1846–47. CPC, 1880. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1886). Dominion annual register, 1882. Donald Swainson, “Kingstonians in the second parliament: portrait of an élite group,” To preserve & defend: essays on Kingston in the nineteenth century, ed. Gerald Tulchinsky (Montreal and London, 1976), 261–77. Peter Baskerville, “Donald Bethune’s steamboat business: a study of Upper Canadian commercial and financial practice,” OH, 67 (1975): 135–49. A. L. Johnson, “The transportation revolution on Lake Ontario, 1817–1867: Kingston and Ogdensburg,” OH, 67: 199–209.

Cite This Article

Peter Baskerville, “HAMILTON, JOHN, (1802-82),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_john_1802_82_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_john_1802_82_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Baskerville |

| Title of Article: | HAMILTON, JOHN, (1802-82) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |