Source: Link

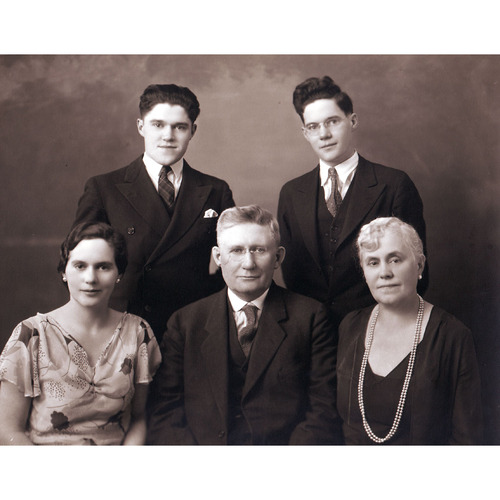

HAMILTON, THOMAS GLENDENNING, teacher, physician, lecturer, politician, psychical researcher, editor, and author; b. 27 Nov. 1873 in Agincourt (Toronto), son of James Hamilton and Isabella Glendenning; m. 26 Nov. 1906 Lillian May Forrester (d. 18 Sept. 1956), a nurse, in Winnipeg, and they had one daughter and three sons; d. there 7 April 1935.

Thomas Glendenning Hamilton’s father was born in Glasgow and immigrated to Canada in 1830. His mother, who was born in Agincourt, Upper Canada, was of Scottish and Irish descent. In 1882–83, as members of a temperance colony, they left Ontario and moved west with their six children to homestead in the Saskatoon area. During the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Louis Riel*] the family opened their home to wounded soldiers for convalescence. Through this contact with the militia, Thomas’s father travelled with the forces when they returned to Ontario, where he fell ill and died in September. The next year the Hamiltons’ only daughter, Margaret, died of typhoid fever.

Isabella Hamilton and her younger sons farmed near Saskatoon until 1891, when they moved to Winnipeg to take advantage of better educational opportunities. T. Glen Hamilton (as he was known) attended the Winnipeg Collegiate Institute until 1894 and then Manitoba College until 1896, taking second-year courses. He financed his education partly by working as a public-school teacher in rural areas and by helping one of his elder brothers, Robert, install knob-and-tube electrical wiring in homes.

Hamilton began studies at Manitoba Medical College in 1899 and graduated with an md in 1903. After interning at the Winnipeg General Hospital, around 1904 he established a private practice specializing in internal medicine and obstetrics. By 1908 he was seeing patients at his family home in the suburb of Elmwood. He would maintain a private practice for the rest of his life, and around 1918 he and his brother James Archibald, also a physician, opened an office together in the Somerset Block, at 294 Portage Avenue.

In 1919 Hamilton became a lecturer in medical jurisprudence and clinical surgery at the medical faculty of the University of Manitoba and an assistant surgeon at the Winnipeg General Hospital; he would retire from the hospital’s staff on 20 Dec. 1934. A leader in the fight for higher professional standards, he called for the annual relicensing of individuals working in the health professions. In October 1920 he became a fellow of the American College of Surgeons. Nine months later, as honorary secretary of the Manitoba Medical Association, he founded the group’s Bulletin (Winnipeg) and was its first editor. He served as the provincial association’s president in 1921–22 and assumed the same role for the Canadian Medical Association the year after. He would remain a Manitoba representative on the executive committee of the national association until 1931, and he also chaired its committee on constitution and by-laws. His medical publications, the first of which appeared in 1922, include reports on hand injuries, ulcerative colitis, and the incidence of goitre among Manitoba schoolchildren.

The Hamiltons were devoted members of the Presbyterian Church and of the United Church of Canada after church union in 1925 [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon]. In keeping with family tradition, Hamilton had signed a temperance pledge in 1906. The next year he was elected an elder of his congregation in Elmwood, a position he would hold until his death. He provided a large donation to help build the King Memorial Church (started in 1913 and finished in 1927), and he served as a trustee of the property and chairman of the building committee.

Active in fraternal organizations, Hamilton belonged to the Oddfellows, the Independent Order of Foresters [see Oronhyatekha*], and the Canadian Club, and he was a charter member of his local masonic lodge. In 1921 he became the first president of the University of Manitoba Alumni Association; from 1931 to 1935, he sat on the Manitoba College board of management.

Although deeply engrossed in his medical work and church obligations, Hamilton was active in public life. As a member of the Winnipeg Public School Board from 1906 until 1915 (chairman, 1912–13) and chairman of the city’s Playgrounds Commission in 1913, 1914, and 1916, he drew upon the insights into educational problems that he had gained as a teacher. As well, he served as a director of the Winnipeg Development and Industrial Bureau around 1913. A Liberal, in 1915 he was elected to the Manitoba Legislative Assembly for Elmwood as a member of the government led by Tobias Crawford Norris. He supported much reform legislation, including bills for women’s enfranchisement (1916), mothers’ allowances (1916), workmen’s compensation (1916), and a system of preferential voting for certain ridings (1920). He piloted the University Amendment Act (1917), which made the Manitoba Medical College part of the University of Manitoba, and wrote the Narcotics Act (1918), designed to restrict the use of opiates and coca-leaf drugs to patients who had prescriptions from physicians. He represented Elmwood until he was defeated in the 1920 election.

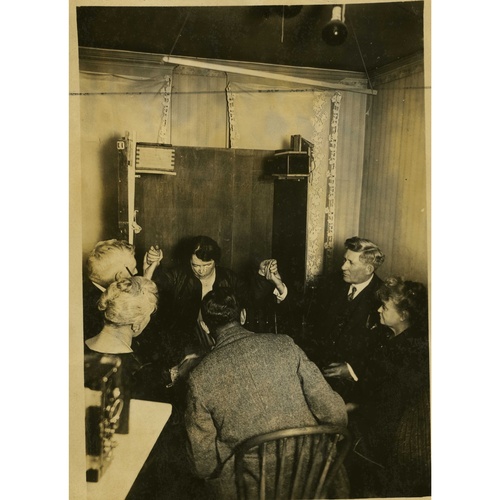

Two years earlier Hamilton had begun to take a serious interest in psychical research and started conducting scientific experiments that were documented by note-takers and through photography. He would investigate a large and varied number of so-called psychic phenomena, such as trance states, telepathy, telekinesis (such as table phenomena and bell ringing), apports, ectoplasmic manifestations, and communication with the deceased, including wax moulds of fingertips alleged to have been created by spirits dipping their fingers into molten wax and then cold water. More than a thousand seances were held in a room designated for the purpose in his home. A number of Winnipeg physicians (including Henry Bruce Chown), lawyers (such as Isaac Pitblado* and Henry Archibald Vaughan Green), clergymen (among them Edwin Gardiner Dunn Freeman), and other leading citizens participated on a regular basis or were invited to witness the photographed table levitations and ectoplasmic manifestations. Hamilton’s wife, Lillian, a trained nurse who had graduated at the top of her class, was his closest associate throughout the research and played a key role in facilitating the experiments.

Though the Hamiltons and their colleagues were not spiritualists, the Hamilton experiments must be considered in the context of the surge in popularity of spiritualism after World War I, when the catastrophic toll of the conflict, coupled with the deaths resulting from an influenza pandemic, drove many to attempt to contact their deceased loved ones through mediums. On 27 Jan. 1919 Hamilton’s son Arthur died of influenza at the age of three. Although Hamilton’s interest in psychical research had begun the previous year, another son, Glen Forrester, would state in a 1986 interview that he believed it was sorrow over this bereavement that “stimulated his [father’s] interest in the psychic field.” Hamilton would later claim to have made contact with the spirits of some of his deceased family members, including Arthur.

Through his experiments Hamilton became part of an international set of respected scientists who sought to make empirical investigations of psychical phenomena, a trend that had emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These contemporaries include Nobel Prize–winning French physiologist Charles Robert Richet and British chemist and physicist Sir William Crookes.

From the start Hamilton had taken measures to preclude the possibility of fraud during the seances. These steps evolved to include a battery of 11 cameras and a remote-control apparatus, shorthand recording of the proceedings, special scrutineers, and physical examination of the medium and sitters both before and after an experiment.

There were three main phases in the Hamilton research. Though Hamilton had read some psychic literature during his undergraduate years, it was in 1918 that he began more in-depth reading in the field, encouraged by his friend William Talbot Allison, a clergyman and professor of English at Wesley College. Allison had shared his investigation of the literary output of a spirit named Patience Worth, who was alleged to be communicating through American medium Pearl Lenore Curran. Hamilton, his pastor, Daniel Norman McLachlan, and Allison conducted some simple experiments into thought transference that convinced them telepathy was possible. In the next phase (1921 to 1927) the Hamiltons turned their attention to the study of telekinesis, particularly table levitations, after Lillian determined that their children’s nanny, Elizabeth Poole, could move objects through paranormal means. When the medium Mary Ann Marshall was introduced to the experiments in 1928, the focus shifted to studying the ectoplasm that emanated from her body, sometimes bearing miniature faces recognized as likenesses of the dead. In this third phase, which lasted until 1934, ectoplasm was photographed in 50 different experiments involving 60 magnesium-flash exposures that recorded 72 separate manifestations.

Several organizations had been formed to evaluate these kinds of experiments, and in 1923 Hamilton had become a corresponding member of the American Society for Psychical Research. Before the year’s end he submitted a report on the investigations involving Poole. According to Hamilton’s daughter, Margaret Lillian, in 1926 the society’s research officer, J. Malcolm Bird, voiced his approval of the control conditions and the validity of the experiments based on personal observation during his visit to Winnipeg. When the Winnipeg Society for Psychical Research was established in 1931, Hamilton was elected president.

The experiments attracted famous visitors. These included, in 1923, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, and in August 1933 politician William Lyon Mackenzie King*, who was leader of the federal opposition at the time. King recorded in his diary that the experiments were “amazing beyond all words.” In 1925 Hamilton began corresponding with Le Roi Goddard (Roy) Crandon, the husband of Ontario-born Mina Marguerite Stinson, the internationally famous Boston medium known as Margery. Her deceased brother, Walter Stuart Stinson, was said to be her spirit control, meaning that he would act and speak through her, relay messages from other spirits, and direct psychical phenomena. From 1928 Walter was believed to have become one of the spirit controls who worked through Marshall and other mediums participating in the Hamilton experiments; he directed the events and dictated precisely when to activate the flash of the camera. Though it was not possible to substantiate that the Boston and Winnipeg Walters were one and the same spirit guide, eventually the Hamiltons stated their belief that the spirits of British author Robert Louis Stevenson, missionary and explorer David Livingstone, and preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon, among many others, had communicated with them.

Hamilton’s psychical research was brought to public attention through 86 addresses he made to audiences in Canada, the United States, and England. He gave his first public lecture on the subject in May 1926 before 125 physicians from the Winnipeg Medical Society. He wrote that his “audience on that occasion doubted neither my sanity nor my sincerity and listened with tolerance and well balanced scepticism.” When the joint convention of the British Medical Association and the Canadian Medical Association met in Winnipeg from 26 to 29 Aug. 1930, Hamilton presented the results of his psychical research to more than 500 delegates and set up a photographic display in the section reserved for hobbies.

Hamilton’s experiments had little negative impact on his reputation among contemporary medical colleagues in Winnipeg. The laudatory obituary in the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association, which insisted on the veracity of the psychic phenomena, was written by Dr Henry Bruce Chown, who had participated in the investigations but did not believe the phenomena should be attributed to spirits. In 1969 Margaret would write that “only rarely did anyone suggest that the phenomena were other than genuine.” The instances in which parapsychologist Joseph Banks Rhine and Winnipeg rationalist and freethinker Marshall Jerome Gauvin insinuated that there was fraud can be discounted. Rhine was never in Winnipeg, despite claiming that the phenomena looked fraudulent. In 1933, in response to Hamilton’s lecture titled “The scientific evidence for survival after death,” Gauvin conceded that some phenomena encountered in psychical research might be genuine. Rather than attribute them to spirits, as Hamilton did, Gauvin preferred to regard them as products of unusual human powers.

In 1935 Hamilton suffered a fatal heart attack. In obituaries he was remembered for his integrity and strong leadership within the Winnipeg community. As considerable as his medical achievements were, it was his experiments that became legendary, both in Winnipeg and in psychical research circles internationally.

Thomas Glendenning Hamilton died before he had published a complete record of his research on psychical phenomena. His youngest son, James D., took responsibility, editing for publication Intention and survival: psychical research studies and the bearing of intentional actions by trance personalities on the problem of human survival (Toronto, 1942). In 1969 his daughter, Margaret Lillian, published a sequel: Is survival a fact? Studies of deep-trance automatic scripts and the bearing of intentional actions by the trance personalities on the question of human survival (London). Hamilton’s experiments earned recognition in the international parapsychology community through his articles published in: American Soc. for Psychical Research, Journal (New York), from 1926 to 1934; British College of Psychic Science, Quarterly Trans. (London), between 1929 and 1934; and Light (London), from 1929 to 1935. Some of them were translated for other periodicals, including the Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie [Journal of parapsychology] (Leipzig, Germany). In 1932 the Daily Sketch (London) published a three-part series of articles authored by Hamilton. The Winnipeg Free Press likewise presented a six-part series in 1933. A list of Hamilton’s publications is available at the Univ. of Man. Libraries, “Hamilton family”: umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/archives/collections/complete_holdings/ead/html/Hamilton.shtml (consulted 31 March 2016).

Univ. of Man. Libraries, Dept. of Arch. and Special Coll. (Winnipeg), mss 14. Elmwood Herald (Winnipeg), 27 Dec. 1934, 11 April 1935. Winnipeg Tribune, 16 Oct. 1912; 12 June 1931; 25 April, 6 May 1933; 8, 16 April 1935. Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 32 (1935): 710–11. CPG, 1920. A. C. Doyle, Our second American adventure (Boston, 1924). Nandor Fodor, Encyclopaedia of psychic science (New Hyde Park, N.Y., 1966). H. E. MacDermot, One hundred years of medicine in Canada, 1867–1967 (Toronto and Montreal, 1967). Man. Medical Assoc., Bull. (Winnipeg), 10 (1930), no.104: 59. Walter Meyer zu Erpen, “Canadian psychical research experiments with table tilting and ectoplasm phenomena in the séance room,” in The Spiritualist movement: speaking with the dead in America and around the world, ed. C. M. Moreman (3v., Santa Barbara, Calif., 2013), 2 (Belief, practice, and evidence for life after death), 205–28. Ross Mitchell, Medicine in Manitoba: the story of its beginnings ([Winnipeg, 1955?]). J. B. Nickels, “Psychic research in a Winnipeg family: reminiscences of Dr. Glen F. Hamilton,” Manitoba Hist. (Winnipeg), no.55 (June 2007): 51–60. F. H. Schofield, The story of Manitoba (3v., Winnipeg, 1913), 2. Soc. for Psychical Research, Paranormal Rev. (London), no.77 (winter 2016).

Cite This Article

Walter Meyer zu Erpen, “HAMILTON, THOMAS GLENDENNING,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_thomas_glendenning_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_thomas_glendenning_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Walter Meyer zu Erpen |

| Title of Article: | HAMILTON, THOMAS GLENDENNING |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |