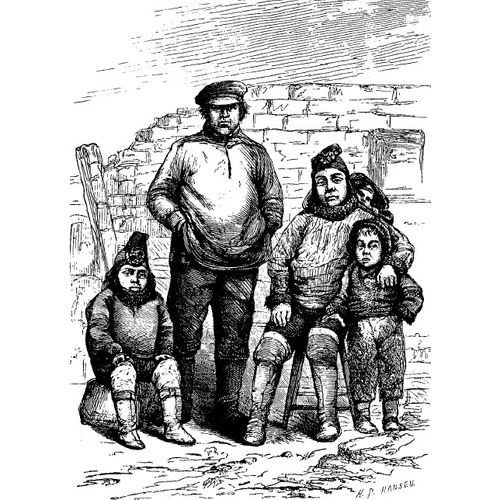

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HANS HENDRIK (called Hans Christian by Elisha Kent Kane*), Greenlander (Inuk) hunter, guide, and dog-driver; b. c. 1834 in Fiskenæsset, Greenland, the second of five children of Benjamin and Ernestine; d. 11 Aug. 1889 at Godhavn, Greenland.

Hans Hendrik spent his youth in Fiskenæsset where he was educated by Moravian missionaries. In July 1853 he was engaged as a hunter on Dr Kane’s expedition in search of Sir John Franklin* and sailed on board the Advance to Rensselaer Harbour, northwest Greenland, where the expedition spent two winters. In June 1854 Hans accompanied William Morton on a sledge journey north along the Greenland coast where they discovered and explored the Kennedy Channel as far as Cape Constitution. Kane found Hans a valuable addition to his crew, especially during the second, enforced, wintering. With morale low and provisions almost exhausted, Hans remained cheerful and continued to hunt when all but he and Kane were sick or injured. Kane repeatedly paid tribute to Hans’s labours and at one point wrote: “If Hans gives way, God help us.” In April 1855 Hans ran away from the expedition, it seems because of a growing fear of Kane whose arrogance upset him. He went to live with the Inuit at Etah, remaining in the north for several years.

In August 1860 Dr Isaac Israel Hayes’s expedition, which was attempting to prove the existence of an open polar sea, landed at Cape York to hire Hans as a hunter. Hans agreed to go and took his wife, Merkut, and his baby son on board Hayes’s ship, the United States. They sailed to Foulke Fjord where the expedition wintered. Hayes had considerably less respect for Hans than Kane, and was continually mistrustful, describing him as “a type of the worst phase of the Esquimau character.” He even accused Hans of being responsible for the deaths from exposure of two members of the expedition, though it is clear from Hans’s account of the incidents that he did his utmost to save both men.

Hans returned south after the expedition, in the summer of 1861, and worked for the Greenland Trading Company in the region of Upernavik. He was at Proven, Greenland, in August 1871 when Charles Francis Hall* asked him to join his north polar expedition. By this time Hans and Merkut had three children and they were allowed to take them on board Hall’s Polaris. Hans and his family were members of the party of 19 which was carried away from the Polaris on an ice floe in October 1872. The party survived a remarkable six-month drift southward through the Davis Strait, and was picked up off the coast of Labrador in April 1873. The survival of all 19 members was entirely due to the efforts of Hans and Ipilkvik (Joe Ebierbing), a Canadian Inuk; the seamen of the party were despondent and ill-tempered and refused to help themselves, whereas Hans and Ipilkvik hunted tirelessly. The leader of the party, George Emory Tyson, rather unfairly criticized Hans for being a less proficient hunter than Ipilkvik and considered him “a little foolish.” Hans was, nevertheless, acclaimed a hero on landing at St John’s, Nfld, and later during a tour of several cities in the United States.

Returning to Upernavik, Hans rejoined the Greenland Trading Company, but in 1875 was again called on for his services, this time by the British Arctic expedition of George Strong Nares. Hans joined the expedition and sailed on board Discovery to Discovery Harbour on the northeast coast of Ellesmere Island. It appears that Captain Henry Frederick Stephenson of the Discovery had great faith in Hans and used his skills extensively; Nares recorded that “all speak in the highest terms of Hans . . . who was untiring in his exertions with the dog-sledge, and in procuring game.” In 1876, after the expedition, Hans returned to the trading company at Godhavn. His last involvement in an Arctic expedition was in 1883 when he accompanied Alfred Gabriel Nathorst on a scientific exploration of west Greenland.

Inuit were frequently employed on 19th-century polar expeditions and received both cash and goods for their services. But Hans was unusual among them not only because of the number of expeditions he took part in, but also because his memoirs were published. These present a rare insight into the Greenlanders’ impressions of explorers and into the brutal treatment the native people often received. It is difficult to make a fair assessment of Hans from the conflicting expedition narratives: some of the explorers found him trustworthy, hard-working, and cheerful; others, notably Hayes, considered him unreliable, incompetent, and morose. The memoirs, however, show him to have been sensitive, responding warmly to affection and fair treatment, but bemused and distressed by the taunting and bullying that was all too often meted out to him and other Inuit.

Hans Hendrik’s memoirs were published under the title Memoirs of Hans Hendrik, the Arctic traveller, serving under Kane, Hayes, Hall and Nares, 1853–1876, trans. H. [J.] Rink, ed. George Stephens (London, 1878).

[C. F. Hall], Narrative of the north polar expedition, U.S. Ship Polaris, Captain Charles Francis Hall commanding, ed. C. H. Davis (Washington, 1876). I. I. Hayes, The open polar sea: a narrative of a voyage of discovery towards the North Pole, in the schooner “United States” (London, 1867). E. K. Kane, Arctic explorations: the second Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, 1853, ’54, ’55 (2v., Philadelphia and London, 1856). G. S. Nares, Narrative of a voyage to the polar sea during 1875–6 in H.M. ships “Alert” and “Discovery” (2v., London, 1878). [G. E. Tyson], Arctic experiences: containing Capt. George E. Tyson’s wonderful drift on the ice-floe, a history of the Polaris expedition, the cruise of the Tigress, and the rescue of the Polaris survivors, ed. Euphemia Vale Blake (New York, 1874). Dan Laursen, “Grpnlændere i forskningens tjeneste II: ‘Hans Hendrik’ fra Fiskenæsset,” Grpnland (Charlottenlund, Sweden), 4 (April 1956): 144–49. Mads Lidegaard, “Hans Hendrik fra Fiskenæsset,” Grpnland, 8 (August 1968): 249–56. H. [J.] Rink, “Om Grpnlænderen Hans Hendriks Deltagelse i Nordpolsexpeditionerne, 1853–1876, under Kane, Hayes, Hall og Nares . . . ,” Geografisk Tidskrift ([Copenhagen]), 1 (1877): 24, 186–92. C. [H.] Ryder, “Grpnlænderen Hans Hendrik,” Geografisk Tidskrift, 10 (1889–90): 140–43.

Cite This Article

Clive A. Holland, “HANS HENDRIK (Hans Christian),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hans_hendrik_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hans_hendrik_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Clive A. Holland |

| Title of Article: | HANS HENDRIK (Hans Christian) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |