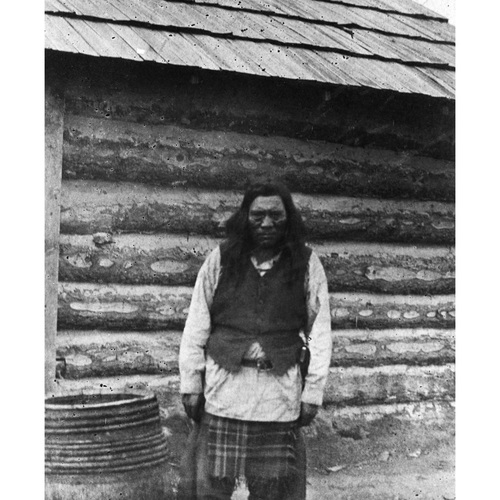

![Chief Isadore, Kootenay chief. Date: [ca. 1887]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Original title: Chief Isadore, Kootenay chief. Date: [ca. 1887]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.12280.jpg)

Source: Link

ISADORE, Kutenai Indian chief; b. probably in the area of Kootenay, B.C.; d. 1894 on St Mary’s Reserve, near Cranbrook, B.C.

Like many Indian leaders in western Canada in the late 19th century, Isadore led his people through a period of change and tension produced by the advance of European settlement. His band, known as the Fort Steele and later as the St Mary’s band, was one of a number of Upper Kutenai groups that lived along the upper reaches of the Columbia and Kootenay rivers in the southeastern corner of British Columbia. The Kutenais, more than any other Indians living west of the Rocky Mountains, were strongly influenced by the cultures of the plains from which they originally came. They ran large numbers of horses and continued to cross the mountains to hunt buffalo every year. By the end of the 1870s, however, Isadore and his hunting parties were returning empty-handed because of the depletion of the herds. The Kutenais therefore had to turn increasingly to cattle-raising and farming at the same time as settlers and gold-miners were beginning to move in on their land. It was in this context that Isadore came to prominence.

By all accounts Isadore was an impressive and dignified individual who, by virtue of his wealth and energy, held considerable sway over his people. Superintendent Samuel Benfield Steele* of the NorthWest Mounted Police later described him as the most influential Indian leader he had met and stated that even Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] and Red Crow [Mékaisto] “dared not, in the height of their power, have exercised the influence that Isadore did.” His authority derived from his personality, his traditional position of leadership, and, by the 1880s, his relationship with the Oblates of Mary Immaculate at St Eugene mission on the St Mary River (he was almost certainly baptized, and sometimes took the advice of the missionaries). But although his influence over his own people was unquestionable, he was not able to control the external forces that were impinging upon them.

Like many Indians in British Columbia, Isadore clashed with the settlers and the government which represented their interests over two related issues: land, and law and order. The Indian reserve commissioner, Peter O’Reilly*, laid out reserves for Isadore’s people in 1884 and, as was his custom, he paid little attention to the natives’ demands or needs. The Kutenais understood the contrast between Indian land policy in British Columbia and on the Prairies as keenly as any Indian group. They were never offered a treaty and received smaller grants of land than their Blackfoot neighbours across the mountains had obtained in signing Treaty No.7 in 1877. Isadore refused O’Reilly’s allocations because they excluded several of the Kutenais’ favourite campsites, especially a fertile piece of land known as Joseph’s Prairie (Cranbrook) that Isadore had cultivated for years. He saw his prestige further undermined three years later when one of his followers, Kapula, was arrested on the ill-founded suspicion that he had been involved in the killing of two miners. Because Isadore considered discipline among his people to be his responsibility, he forcibly freed Kapula from the jail at Wild Horse Creek in May 1887. This action aroused fears of an “Indian uprising” among the settlers, who called upon the British Columbia government to intervene.

The province was more concerned with security than with making concessions to the Indians over land. A provincial commission persuaded Isadore to hand Kapula over to them, and a detachment of the NWMP under Steele was brought in from Lethbridge (Alta). Steele found the Kutenais generally to be a law-abiding and disciplined group, and he released Kapula in August after a brief investigation. On 22 September three provincial commissioners, including O’Reilly, were sent to the Kutenais to deal with the land question. They examined the reserves while Isadore and his band were absent, and confirmed O’Reilly’s earlier decision that Joseph’s Prairie had to be relinquished to its owner, Colonel James Baker, a rancher and member of the Legislative Assembly. Isadore was warned by Steele that unless he abided by the commission’s findings another chief would be put in his place. Whatever Steele may have thought of the justice of these rulings, it was his duty to enforce them. Isadore seems to have been impressed with Steele’s show of force and to have recognized the futility of armed struggle. He could do little but acquiesce.

Isadore withdrew to a piece of land on the Kootenay River that he had been allocated by the provincial authorities, and through the last few years of his life he devoted his energy to improving his farm. During the winter of 1893–94 influenza attacked the Kutenais, and many of the old people, Isadore among them, succumbed to the disease. Indian agent Robert Leslie Thomas Galbraith recorded the chief’s passing with the note that he was “one of the most remarkable men of the tribe, an Indian of strong will, who had a great influence for good or evil over his people.”

Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1885–95, esp. 1895, no.14: 162 (annual reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs). S. B. Steele, Forty years in Canada: reminiscences of the great north-west . . . , ed. M. G. Niblett (Toronto and London, 1918; repr. 1972). R. E. Cail, Land, man, and the law: the disposal of crown lands in British Columbia, 1871–1913 (Vancouver, 1974). R. [A.] Fisher, Contact and conflict: Indian-European relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890 (Vancouver, 1977). H. H. Turney-High, Ethnography of the Kutenai (Menasha, Wis., 1941). J. C. Yerbury, “Nineteenth century Kootenay settlement patterns,” Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology (Edmonton), 4 (1975), no.4: 23–35.

Cite This Article

Robin Fisher, “ISADORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isadore_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isadore_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robin Fisher |

| Title of Article: | ISADORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |