Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

LINDLEY, SARAH (Crease, Lady Crease), artist, socialite, and diarist; b. 30 Nov. 1826 in Acton (London), England, eldest daughter of John Lindley and Sarah Freestone; m. there 27 April 1853 Henry Pering Pellew Crease*, and they had three sons and four daughters; d. 10 Dec. 1922 in Victoria.

The eldest daughter of a distinguished botanist, university professor, and author, Sarah Lindley grew up in an environment steeped in plant lore and scientific curiosity, with an emphasis on gardening, horticulture, and specimen collecting. As a young girl, she attended Mrs Gee’s school in Hendon (London) and received private art lessons from family friend and noted portraitist Charles Fox. Inspiration and instruction in botanical illustration with watercolours came from Sarah Ann Drake, chief illustrator in her father’s employ. Fox taught watercolour and pencil sketching and introduced Sarah to woodblock printing and copperplate engraving. These techniques would be crucial to her later work, allowing her to translate her sketches into a publishable format. Between 1842 and 1858 she produced pen-and-ink botanical illustrations to accompany her father’s numerous publications, notably the Gardeners’ Chronicle (London), which he helped to found in 1841 and would edit until his death in 1865, and The vegetable kingdom . . . (London, 1846). Many of these sketches she also translated into woodblock prints. She was thus able to study botany and earn pocket money, yet she remained in the separate sphere of domestic life as a female dependent.

In 1848 Sarah met a law student and friend of her brother, Henry Pering Pellew Crease. They became engaged in June 1849, but the engagement was not publicly announced since Crease was obliged to travel with his family to Upper Canada immediately after taking his bar exams in July. During their separation Crease attempted to find suitable employment. John Lindley would not compromise in his expectations for his daughter. Sarah and Henry corresponded continuously over a period of almost 18 months. Her charming letters shyly reveal the thoughts and emotions of a young woman in love.

Crease returned to England in December 1850 and the couple eventually married on 27 April 1853. After setting up a household in Notting Hill (London), he became a mining manager in Cornwall; his family moved there in 1856. Following his resignation in 1857, he left England and the next year he settled in Vancouver Island, where he became a barrister. Sarah arrived with their three daughters in February 1860.

The family lived in Victoria until 1862. Crease had been appointed attorney general of the mainland colony of British Columbia in October 1861, so they moved to New Westminster, the capital, and resided at Ince Cottage. They remained there until 1868, when they returned to Victoria. Financial uncertainty plagued the family, but in 1872 they began to construct Pentrelew, an Italianate-style country house, which would soon be surrounded by lush gardens.

Over an 18-year period, from 1854 to 1872, Sarah bore seven children, the youngest when she was 45. She coped with their measles, mumps, diphtheria, and scarlet fever, but still three children would predecease her. Henry Hooker, born in 1869, died a year after his birth. Barbara Lindley would die in 1883, after many years of indifferent health, and in 1915 Mary Maberly would die of cancer. Sarah loved her family, but was a strict disciplinarian who set high moral standards.

Because of her husband’s prominent position – he had been appointed a judge in 1870 – Sarah and her family were part of the immigrant social elite. Despite continued worry over finances, the family maintained a façade of genteel, cultured living and participated in a wide variety of activities. The sons completed their education in England and the daughters travelled there to attend art classes, meet relatives, and further their social connections. Until 1875 Sarah employed domestic help only sporadically, assuming the principal load of household responsibilities and training her daughters to share in the duties. In the evenings she assisted her husband in his business affairs by performing the role of clerk, copying his correspondence and assisting with accounts. This unpaid labour was an economic necessity. Unfortunately, it strained her eyesight.

As befitted her role as a social leader, Sarah immersed herself in charitable works. Both she and her husband were generous financial supporters of the Church of England, contributing whenever possible to special projects. Never in a position of complete financial security, Sarah often preferred to volunteer her time and lend her name to charitable causes rather than donate funds. Thus she taught Sunday school for over a decade, worked on committees to establish a women’s infirmary, served from 1899 to 1901 on the women’s auxiliary to raise funds for the Royal Jubilee Hospital, was a founding member in 1894 and honorary president of the Local Council of Women of Victoria and Vancouver Island, and in 1910 became patron of the Island Arts and Crafts Society.

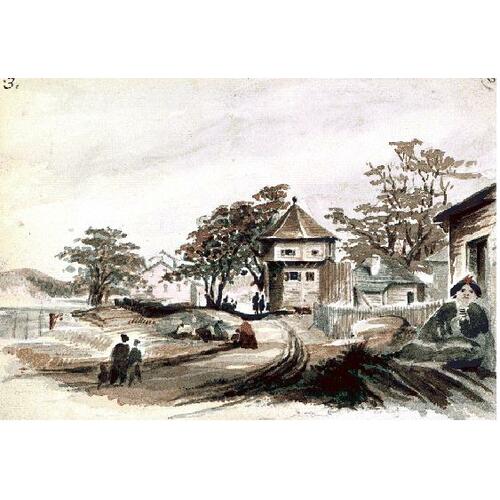

Sarah’s art occupied a prominent part of her leisure time. In 1860 she had executed a series of 12 watercolours depicting the Hudson’s Bay Company fort and the town of Victoria; they remain important historical documents. These detailed and realistic paintings received a wide audience on their initial showing in 1862 at the International Exhibition in London, where they were labelled “the work of a colonial amateur.” Two of the sketches were later translated into lithographs to illustrate Richard Charles Mayne’s Four years in British Columbia and Vancouver Island . . . (London, 1862) and they would be reproduced in numerous publications over the years. In 1862 she sketched landscapes of New Westminster, Hope, Yale, and the Fraser River and a decade later she documented the house and gardens of Pentrelew. Her sketches in 1877 of the newly consecrated St Andrew’s Church at Comox and of the Courtenay River were made into woodblock prints for the Church of England’s annual report on British Columbia’s missions. By the late 1870s her artistic activity had diminished and it soon ceased as failing eyesight (eventually diagnosed as glaucoma), compounded by years of eye strain, impaired her abilities. In 1880 she accompanied her husband on circuit during a three-month trip from New Westminster to the Cariboo region. Her daily diary remains an important record of travel in the province, containing details of events, people, and landscapes. Sarah became Lady Crease in 1896, when her husband was knighted. Henry Crease retired that year and the social obligations of public life ceased. Until 1919, when she broke a hip, she remained active in community works and corresponded with friends and family around the world.

Ever the communicator, Sarah Crease left an impressive legacy. Several hundred of her ink, pencil, and watercolour works are extant, a prodigious and outstanding body of sketches. Together with her voluminous correspondence and numerous diaries, these records provide unparalleled documentation of British Columbia’s colonial and post-confederation immigrant society.

Sarah Lindley’s voluminous correspondence and her diaries can be found in the BCA (MS-0054; MS-0055; MS-0056; MS-2879), together with over 400 of her paintings and sketches. She transmitted her love of record-keeping to her children, whose works of art, letters, and diaries are also held at the BCA.

K. A. Bridge, Henry & self: the private life of Sarah Crease, 1826–1922 (Victoria, 1996); “Lindley documents in the British Columbia Archives,” in John Lindley (1799–1865): gardener-botanist and pioneer orchidologist: bicentenary celebration volume, ed. W. T. Stearn (Suffolk, Eng., 1999), 191–92; “Two Victorian gentlewomen in the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia: Eleanor Hill Fellows and Sarah Lindley Crease” (ma thesis, Univ. of Victoria, 1984). C. B. Johnson-Dean, “The Crease family and the arts in Victoria, British Columbia” (ma thesis, Univ. of Victoria, 1981); The Crease family archives: a record of settlement and service in British Columbia (Victoria, 1982).

Cite This Article

Kathryn Bridge, “LINDLEY, SARAH (Crease) (Lady Crease),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindley_sarah_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindley_sarah_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kathryn Bridge |

| Title of Article: | LINDLEY, SARAH (Crease) (Lady Crease) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |