Source: Link

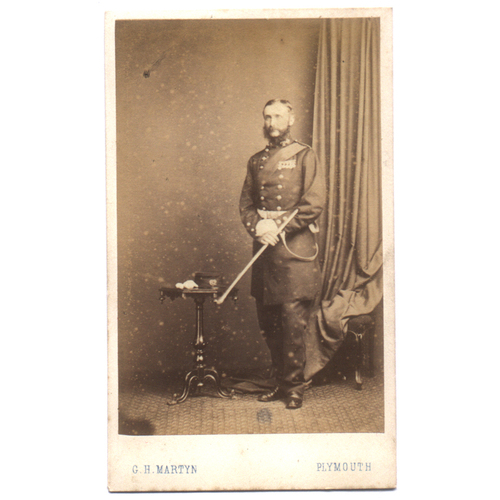

LUARD, RICHARD GEORGE AMHERST, army officer; b. 29 July 1827 in England, son of John Luard and Elizabeth Scott; m. 8 Oct. 1863 Hannah Chamberlin in Hale, Surrey, and they had six sons and a daughter; d. 24 July 1891 in Eastbourne, Sussex, England.

The eldest child of an army officer, Richard George Amherst Luard was educated at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and was commissioned an ensign in the 51st Foot on 6 July 1845. The same year he transferred to the 3rd Foot, in which he rose to captain and was adjutant for three years. He transferred again, in 1854, to the 77th Foot, serving with it in the Crimea until 1855, when he became a deputy assistant adjutant general. Mentioned in dispatches for his part in the siege of Sevastopol (U.S.S.R.), he became a brevet major in November 1855. On returning to the United Kingdom, he was brigade major in 1856–57 of the Dublin District. Luard saw active service again as a brigade major in an expedition to China (1857–58) and was again mentioned in dispatches. He was promoted substantive major in 1857 and brevet lieutenant-colonel the following year.

Back in England, he was aide-de-camp in 1859–60 to the general officer commanding, South West District, and then assistant inspector of volunteers until 1865; he was promoted brevet colonel in 1864. Following a period on half pay and promotion to major-general, he was assistant military secretary in Halifax to Lieutenant-General William O’Grady Haly*, general officer commanding in British North America, from May 1873 to September 1875. He next served, until 1877, as assistant adjutant and quartermaster general, Northern District, in Britain.

On 5 Aug. 1880 Luard was appointed general officer commanding the Canadian militia. Like his predecessor, Lieutenant-General Sir Edward Selby Smyth, he was selected by the Duke of Cambridge, commander-in-chief of the British army, not by the Canadian government. Luard’s genuine qualifications, experience with a part-time volunteer force, and previous service in Canada were unfortunately countered by his lack of tact and fearsome temper. It has even been suggested that he had been due to succeed to the colonelcy of a British regiment, but that Cambridge wanted to make room for a more desirable candidate.

Luard was quick to size up his command. In January 1881, in his first report to the new minister of militia and defence, Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, he advocated the establishment of permanent infantry training schools (two such units had existed since 1871 to train the militia artillery) and more training for the whole force. To pay for such a plan within the limits of the funds voted by parliament, Luard proposed to cut the militia almost in half, to 20,000. At the same time, he sought a better force. Although he could praise such city units as the Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto, commanded by William Dillon Otter*, he emphasized the need for greater discipline generally and was prepared if necessary to make examples of militiamen displaying unsoldierly conduct. He deplored some of the “extraordinary costumes” worn by the more affluent units and urged workmanlike uniform. When he recognized that district staff officers had become stale and subject to political influence, he rotated them and brought in a compulsory retirement age of 63.

Such measures antagonized both militia officers and permanent staff officers. They also threatened to interfere with the militia as an instrument for dispensing political patronage at the local level, thus bringing Luard into conflict with Caron. Caron in turn dabbled in what the general regarded as strictly military matters. Relations had reached such an impasse by early 1882 that Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] wrote to Cambridge urging him to find another appointment for Luard, who could ill afford to resign. For his part, the prime minister, an exasperated Sir John A. Macdonald, was content to leave Luard in command. “It is to be hoped that with Your Excellency’s good counsels the General will draw his salary and deserve it by doing as little as possible,” he wrote to Lorne. “On the other hand I shall endeavour to check Caron’s untutored zeal.” Both Lorne and Cambridge realized that Luard’s dismissal might lead the Canadians to propose their own nominee for the post, and he might not be a British regular officer.

Meanwhile, Luard’s outbursts were alienating militiamen and the Canadian public alike. In his first inspection of the militia at London, Ont., in the summer of 1881, he publicly scolded Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Campbell of the 27th (Lambton) Battalion of Infantry for his incorrect uniform, made by a Sarnia tailor, and the incident had to be smoothed over by the governor general. In 1882, while attending the Dominion Rifle Association matches at Rockcliffe Park (Ottawa), Luard personally arrested, supposedly for cheating, Major Erskine Scott, acting commanding officer of the 8th Battalion of Rifles, a prominent resident of Quebec, a good Conservative, and a friend of the minister. Caron ruled that Scott had not been subject to military law at the time, but Luard wrote to the newspapers about the incident and later tried, by every means in his power, to prevent Scott’s promotion to command the battalion.

The final break came at a militia-camp inspection at Cobourg, Ont., in September 1883. Luard was intensely critical of the amateur soldiers. “During the field evolutions which took place, if the slightest irregularity occurred, the General seemed to become beside himself,” the Toronto Globe reported. At an officers’ luncheon following the inspection, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Trefusis Heneage Williams*, commander of the 46th (East Durham) Battalion of Infantry and a Conservative mp, took offence at a supposed slight of mps by a guest, Colonel Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski, patron of the Dominion Rifle Association. Luard heatedly intervened to argue against Williams, who subsequently used his influence to help secure the general’s removal. The new governor general, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], persuaded Luard to go on leave and later to resign, Cambridge to offer him a new position, and Williams to withdraw his grievance in the House of Commons.

Such clashes and Luard’s controversial removal tended to obscure the progressive measures adopted during his tenure. His concept of permanent militia training schools, in fact a tiny regular army, was implemented, but he cannot be credited with the formation of them. Schemes for this type of force had been put forward periodically since the withdrawal of the British regulars from central Canada in 1871. A proposal from the popular adjutant general, Colonel Walker Powell*, was regarded as opportune by Macdonald and Caron in 1883, and in April of that year Caron skilfully piloted through the commons a militia bill that allowed the government to raise a troop of cavalry, three companies of infantry, and three batteries of artillery, all for permanent service. In the setting up of these embodied training schools and the determination of appointments, Luard was virtually ignored.

On 5 March 1884 Luard left Ottawa for Aldershot, England, to command a brigade; he was promoted lieutenant-general on 1 December. He continued to serve as honorary colonel of the 2nd Gloucester Engineer Volunteers, a position he had held since 1881. In his last years he became a cb and was a justice of the peace in Sussex. In 1885 two of his sons, both of whom had attended the Royal Military College of Canada, received commissions in the British army.

Although Luard recognized the shortcomings of the Canadian militia and had realistic remedies, his influence in Canada was almost entirely negative. He angered amateur soldiers, without whose goodwill the militia could not exist, and he failed to appreciate its political dimension. Of more consequence, from the British point of view, he undermined the respect for a British officer as general officer commanding, so painstakingly built up by his predecessor. The result was that the Canadian government seriously considered a retired officer resident in Canada, Major-General John Wimburn Laurie, as his successor, though Colonel Frederick Dobson Middleton was finally selected.

Can., National Defence, Directorate of History (Ottawa), Desmond Morton, “The Canadian militia, 1867–1900; a political institution” (2v., typescript, 1964). NA, MG 26, A: 32065–68; MG 27, I, B4, 1: 769–71, 773–74, 779–81, 792–93, 1427–30, 1499–1502, 1509–10, 1551–52, 1563–66, 1637–42, 1787–92; D3, files 3082, 6246; MG 29, E72 (mfm.). Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Militia orders (Ottawa), 5 Aug., 8, 15 Oct. 1880; Report on the state of the militia (Ottawa), 1883; House of Commons, Debates, 1881–84; Parl., Sessional papers, 1880–81, no.9; 1882, no.9. Gentleman’s Magazine (London), July–December 1863: 638. Globe, 24, 26 Sept. 1883. Burke’s landed gentry (1871; 1921; 1952). DNB. Dominion annual reg., 1882: 59–60, 200–1; 1884: 321; 1885: 230, 232. Hart’s army list, 1883. O. A. Cooke, “Organization and training in the central Canadian militia, 1866–1885” (ma thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1974). Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). R. A. Preston, Canada and “Imperial Defense”; a study of the origins of the British Commonwealth’s defense organization, 1867–1919 (Durham, N.C., 1967); Canada’s RMC; a history of the Royal Military College (Toronto, 1969).

Cite This Article

O. A. Cooke, “LUARD, RICHARD GEORGE AMHERST,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 25, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/luard_richard_george_amherst_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/luard_richard_george_amherst_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | O. A. Cooke |

| Title of Article: | LUARD, RICHARD GEORGE AMHERST |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 25, 2026 |