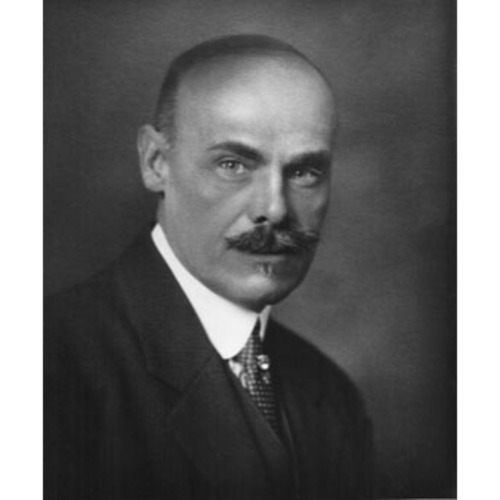

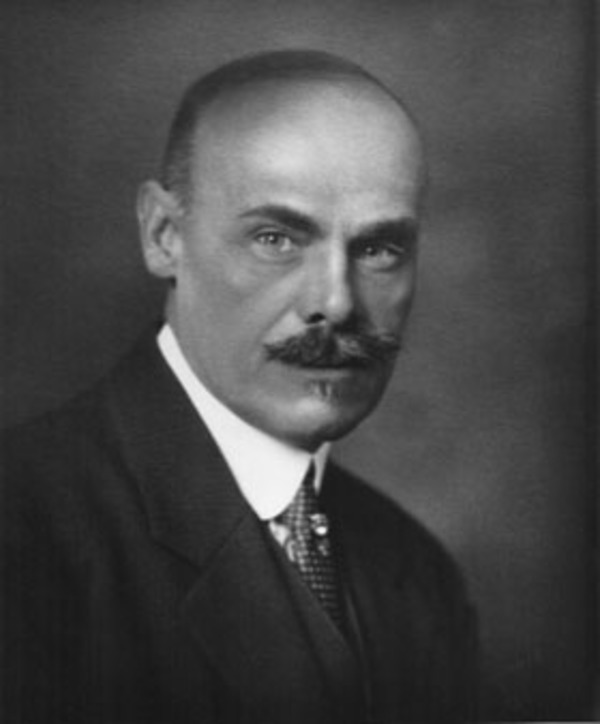

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MARCHAND, JEAN-OMER (baptized Arthur-Omer and called John Omer in notarized documents, he signed J. O. Marchand), architect and professor; b. 28 Dec. 1872, probably in the parish of Saint-Joseph, Montreal, son of Elzéar Marchand and Agnès Martel; m. 16 Feb. 1907 Eva Le Boutillier (Le Bouthillier) in the parish of Sainte-Cunégonde in the same city, and they had two children, one of whom was stillborn; d. 11 June 1936 in Westmount, Que., and was buried on the 13th in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal.

The second in a family of six children, Jean-Omer Marchand grew up in the working-class neighbourhoods of southwestern Montreal. In 1882 his father, a carpenter, and later a merchant, bought two houses in Sainte-Cunégonde (Montreal); his mother would manage the Marchands’ grocery store in one of them. At about the same time, Jean-Omer was taking a commerce course at the Académie de l’Archevêché, run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Brother Marcellian introduced him to architecture by having him reproduce, along with the future architects Ludger Lemieux and Joseph-Honoré MacDuff, the plans of the Collège du Mont-Saint-Louis. Around 1888 Marchand was apprenticed to the architects Maurice Perrault* and Albert Mesnard, who were at the height of their fame. In the evenings he attended classes at the Catholic Commercial Academy of Montreal, from which he received a diploma in 1889, and later at the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec in Montreal. On the advice of the Sulpician Paul De Foville, he went to Paris in 1893 to study architecture at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. During the same period Léon-Alfred Sentenne, a Sulpician and the curé of the parish of Notre-Dame in Montreal, was sending artists to France to develop their skills. This local phenomenon was part of a much larger movement, brought about by the powerful influence on American culture of the beaux-arts style, which prompted many young students to train in ateliers connected to the Parisian institution. Unlike the picturesque fantasy of the High Victorian period, beaux-arts sought to submit aesthetics and planning to academic rigour. While in Paris, Marchand became friends with a number of artists. At La Boucane (where Canadians, especially students, gathered more or less regularly in the evenings) he met, among others, Joseph Saint-Charles, Henri Beau*, and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté.

In February 1894 Marchand failed the difficult entrance examinations of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. He took them again in the summer and passed, with the result that he enrolled on 1 Aug. 1894 in the second-level class at the studio of architect Gaston Redon, a brother of the symbolist painter Odilon. He was promoted to the first class on 27 July 1897. He was a brilliant student since, in the competitive system that characterized the institution, he won several medals and the Prix Chapelain, which was awarded by the Société Centrale des Architectes in 1898. In 1902 Marchand became the first Canadian to graduate from the venerable school. It is not known how he was able to pay for such a long stay. It is thought that in addition to using his savings, Marchand perhaps, through luck, won some money by betting on the races. Like many of his colleagues he also had a job, possibly several. For example, Joseph-Israël Tarte*, the minister of public works, hired him to set up the Canadian stands for the Paris universal exposition of 1900.

On 3 Dec. 1902, after his return to Montreal, Marchand was admitted to the Province of Quebec Association of Architects (PQAA). On the 18th he incorporated the partnership he had formed a month earlier with Samuel Stevens Haskell, an American architect who had studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1890–91 and in Paris from 1894 to 1899. Haskell had managed the New York City branch of the architect Cass Gilbert’s agency and had already acquired solid expertise in running large projects. The two architects, who had met in Paris, set their sights on doing business in Montreal and New York. Because they did not succeed in New York but did in Montreal, by 1905 Haskell had moved to Montreal, and in 1907 he became a member of the PQAA. Indeed, owing to Marchand’s education, as well as the support of the Roman Catholic clergy along with that of the political and business community (especially the francophone sector), the Montreal office quickly won several prestigious commissions, including one in 1902 from the Sulpicians to rebuild the chapel of the Grand Séminaire de Montréal (1905–7). This creation, which was monumental and solemn, drew high praise and enhanced the architects’ reputation. The impeccable finishes testified to Marchand’s high standards. In the interest of using authentic materials, he imported stone from Caen, France, to cover the interior walls. The partnership between the architects would come to an end with Haskell’s death in 1913.

Marchand also favoured collaboration with other colleagues, thereby increasing his influence. Thus, in 1903 he began working with Maurice Perrault on Notre-Dame Hospital (partially constructed in 1903–11) and St Paul’s Hospital (1903–5) in Montreal. In 1904 he joined the brothers Edward* and William Sutherland Maxwell to design the belvedere of the park on Mount Royal (1904–6). In 1905, with Raoul-Adolphe Brassard, he signed a tender for services for Bordeaux Jail (1907–12). They were awarded this contract in 1906. A few years later Marchand took part in the construction of the library, restaurant, and boiler room of the legislative building in Quebec City (1910–17) with Georges-Émile Tanguay*. Marchand and Haskell’s partnership with Ernest Hébrard, and possibly with his brother Jean, demonstrated the amicable relationship that they maintained with some of their French colleagues. In the spirit of the City Beautiful movement – an American trend inspired by the Paris of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, namely the urban adaption of beaux-arts architecture – the four architects drew up an ambitious plan for a municipal centre, which was never executed. In 1916, with the Toronto architect John Andrew Pearson, Marchand participated in reconstructing the centre block of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. This collaboration reinforced his Canada-wide reputation, which he had already acquired in erecting the cathedral at St Boniface in Winnipeg (1904–8).

Until the end of World War I, Marchand’s career was unmatched by that of any of his French-speaking colleagues, but when Ernest Cormier* returned from Europe in 1918, the situation changed. Henceforth Marchand was no longer the only Canadian architect holding a diploma from the French government. Moreover, Cormier had also trained as an engineer and he returned with the prestigious Henry Jarvis Studentship awarded by the Royal Institute of British Architects. Perhaps owing to solidarity between graduates of the same school at a time when the post-war economy was still shaky, or for fear of rivalry, the two architects collaborated from 1918 to 1922. They won contracts for some large projects in Montreal, such as the Dubrûlé office building (1919–21) and the School of Fine Arts of Montreal (1922–23). They shared the contract for the annex to the Montreal courthouse (1920–26) with Louis-Auguste Amos, the brother-in-law of Premier Sir Lomer Gouin*, and Charles Jewett Saxe. Marchand, Cormier, and Amos, along with Dalbé Viau and Louis-Alphonse Venne on the one hand, and David Jerome Spence on the other, were the three parties on the committee for the reconstruction of the Montreal city hall, which had burned down in 1922. Marchand was its chairman. At the same time, the project for the courthouse annex brought the tensions between Cormier and him to a head. Although Marchand had left the spotlight to Cormier and Amos for this contract, Cormier seemed displeased with the business relationship. Marchand may have underestimated the independent spirit, the creative aspirations, and the desire for his just due of this man 13 years his junior. At least that is the impression given by the letters Marchand sent him. While on vacation at his summer residence in Trois-Pistoles, he made design suggestions to Cormier, who was still in Montreal working on the courthouse. The break led to legal proceedings. On 9 Oct. 1925 an arbitral decision, handed down by the lawyer and politician Joseph-Léonide Perron* at the Superior Court, required Cormier to pay Marchand a sizeable percentage of the revenue from the courthouse contract. Now permanently estranged, the two architects kept up their rivalry with the Université de Montréal project. Marchand resented the fact that Cormier won this highly desirable contract in 1925. Like their opposite personalities, the age difference between Cormier and Marchand had a bearing on the conflict. It was reflected in their dissimilar sensibilities with respect to the nascent modern aesthetics that sought, among other things, to break free from dependency on historical ornamentation. But in the years ahead Marchand would renew his confidence in young architects and would go into partnership with three of them: Lucien F. Keroack, Henri Talbot-Gouin, and Victor Depocas. The simpler decoration of some of the buildings from this period, including the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court (1927–29) and La Visitation school (1930–33), suggests that Marchand was adapting his style to recent developments in architecture. The new approaches troubled him, for they presaged the disappearance of a culture he had stoutly defended. In an interview, Depocas reported that Marchand had said to him: “It is easy for you to do modern architecture, [but] I have to set aside everything I have learned.”

Marchand’s architecture is unique in many respects. To be sure, it was part of a North American movement and Marchand, who had hoped for success in New York, was not impervious to American influence. To a large extent, however, the Americans had translated the lessons of the beaux-arts style into a strict and imposing classical revival, which sometimes appeared to adhere to a set formula. Most Canadians who were sensitive to the beaux-arts trend followed them in this direction, but not Marchand. In his first contracts, whenever the budget permitted, he chose opulence over simplicity. Furthermore, for him beaux-arts did not signify a particular style, but rather an approach to design. Plans, spaces, volumes, and proportions were priorities. Although his work was predominantly classical, the styles in fact were varied. For his own house in Westmount (1912–14) and in his plan for the competition for the Bibliothèque Saint-Sulpice (1911), he adopted the Tudor style out of deep admiration for the Anglo-Saxon culture, which he valued for its civility. On more than one occasion, his buildings were adapted to local context and skills, to the point that stylistic considerations were disregarded in favour of well-crafted stonework.

In general, Marchand’s work is distinguished by the influence of French architecture. A pioneer in the use of concrete, which was well established in France but rare in Canada, the architect employed it in building the mother house of the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame in Montreal (1904–6), which had a dome inspired directly by that of the Basilica of St Martin in Tours, France, the work of Victor-Alexandre Laloux. In this creation, which Professor Pierre-Richard Bisson would describe as a “world-class building,” Marchand also demonstrated his mastery of academic precepts by taking liberties with history: this blind dome does not cover the chapel choir but rather the narthex, thereby making it more visible from the exterior. Furthermore, with lateral sections built at right angles to the main facade, he reinvented a monastic symbolism that had endured in the Montreal region since the time of the French regime. To raise the height of the Montreal city hall (1923–25), he took as his model the rooftop silhouette of the city hall in Tours, designed by Laloux. He may have drawn his inspiration for the interior of Sainte-Cunégonde church in Montreal (1904–7) from the chapel of the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, itself a copy of the royal chapel at Versailles. Finally, Marchand built the Bain Généreux in Montreal (1924–27), for which he adapted the concrete structure of the bathing facility at La Butte aux Cailles in Paris, created by Louis Bonnier.

This avowed francophilia is what gives Marchand’s work its chief significance and ideological reach. Faithful to his alma mater, he belonged to a clan, an international elite of architects with qualifications from the French state. For him, the fine arts represented the genius of French culture, whose influence was being felt throughout the world, including the United States. In this context, French Canada benefited from a privileged position. In his speech marking the inauguration of the fine-arts schools in Montreal and Quebec City, as published in Le Soleil on 24 Nov. 1922, Marchand said he saw, in the re-establishment of ties with the mother country, the advance of French Canadian culture, which had the potential to cross frontiers: “It is this French tradition, unhappily gone, for want of an environment favouring its study and for lack of encouragement, it is this tradition, we say, that it is important to revive in the country.… Through these schools, the quality of the teaching that will be provided in them, and the marvellous natural aptitude of our Canadian youth, French art will flourish again in our province and our race will regain once and for all the place to which it is entitled in one of the noblest manifestations of the human spirit.” On the afternoon of the inauguration, Marchand was elected president of the Conseil Supérieur des Beaux-Arts. In this capacity he helped bring to fruition the plan of the provincial secretary of Quebec, Louis-Athanase David*, to introduce education in the fine arts. He had also been honorary professor of perspective at the École Polytechnique of Montreal from 1904 to 1911 (in 1907 the school set up a new program in architecture).

Marchand’s influence extended beyond the field of architecture. His friend, the French painter Emmanuel Fougerat, was appointed director general of fine-arts education for the province of Quebec (1924–31) and principal of the School of Fine Arts of Montreal (1922–25). In 1909 the provincial government had assigned Marchand the task of preparing a report on the competition for a monument to the memory of Honoré Mercier* in Quebec City. For nationalistic reasons, the award of the first prize to France’s Paul Chevré rather than to the Canadians Louis-Philippe Hébert* and Alfred Laliberté* had been challenged. In 1918 Marchand was also a member of the committee that chose Laliberté for the monument to honour Adam Dollard* Des Ormeaux in Montreal. In 1920 he was on the first jury for acquisitions of works of art to form a collection for the future Musée de la Province in Quebec City. He belonged to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and, from 1925, sat on the board of directors of the National Gallery of Canada [see Eric Brown]. In addition, he was reportedly a member of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York. Already a member of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Marchand joined the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1925. In 1926 the government of France made him a chevalier of the Legion of Honour for his work and his contribution to the dissemination of French culture. In 1927 Marchand was elected president of the Province of Quebec Association of Architects, an organization in which he had participated off and on since his partnership with Haskell. During his one-year term of office, the PQAA succeeded in convincing the government to reduce the duration of architects’ legal liability from ten years to five.

Marchand’s family circle, and especially his wife’s relatives, played an important role in his career. Eva Le Boutillier, the granddaughter of John Le Boutillier*, was cultured, charming, and well known, though she had no fortune. She wholeheartedly supported her husband in his meteoric rise in society. She also shared his love for Paris, to which he had introduced her during the 1900 exposition. Marchand found a firm ally in the French architect Jules Poivert, who would marry Eva’s sister Elizabeth and become the head of the architectural section of the École Polytechnique in 1909. Poivert would hold the same position at the School of Fine Arts of Montreal after it was created in 1923. Another of Eva’s sisters, Alice, married the journalist Olivar Asselin in 1902. The Marchands, more comfortable financially than the Asselins, came to their assistance from time to time by, for instance, lending them goods and furniture to add lustre to an evening party. A tireless worker, with an occasionally brusque temperament, Marchand could enjoy a joke when he was in the mood. He appreciated the keen mind and wit of his brother-in-law Poivert and admired the ideas of Asselin. Among all of these people, he found, on the one hand, the extension of the cultured environment that had filled him with enthusiasm in France, and, on the other, pivotal figures in the influential network that he had created.

Jean-Omer Marchand, who had grown up in the working-class neighbourhoods of Montreal and who literally had lived beside the Grand Trunk Railway tracks, resided after his marriage on the heights of Westmount, a geographical symbol of his rise in society. He adopted a lifestyle to match. His house on Wood Avenue was designed to showcase his collection of decorative objects, furniture, and European books. He went about in a chauffeured Cadillac and played golf regularly. His francophilia led him to import his wine and a few choice specialties from France. His road to success had necessitated a long detour by way of France, which had remained in his eyes the ultimate cultural reference point. Marchand owed everything to his education, as he knew very well. This benefit was no doubt the gift he wanted to bestow on his daughter, Raymonde, his only child, when he sent her to study in Paris at the age of 12. In fact, Marchand represented the new bourgeoisie of the early 20th century, which owed its status to its education and, confident of its wisdom, sought, in its application, to improve Canadian society and to give it a window on the world.

The author would like to thank Raymonde Marchand, daughter of Jean-Omer Marchand, for the information she provided during two interviews.

Marchand is the author of: “Sketching competitions in the second class of the School of Fine Arts, Paris,” Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 9 (1896): 52, and “L’influence de l’École des beaux-arts aux États-Unis,” École Polytechnique de Montréal, Bull. (Montréal), 2 (1914): 97–103.

It is owing primarily to long and meticulous research by Professeur Pierre-Richard Bisson, architect and architectural historian, that documentation on Marchand has been gathered. The Pierre-Richard Bisson coll., held at the Bibliothèque d’Aménagement de l’Univ. de Montréal, includes Bisson’s archives, and, among others, sources from: Arch. Nationales à Paris; BANQ-CAM; École Polytechnique de Montréal; New-York Hist. Soc.; Royal Instit. of British Architects; and Soc. Française des Architectes à Paris. In addition to interviews with members of Marchand’s staff and his family, the collection comprises copies of newspaper articles published in Paris-Canada (Paris) and La Presse as well as an unpublished work by Bisson: “Jean-Omer Marchand (1872–1936): architecture, commande et idéologie” (paper presented at a seminar at the Univ. Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1983).

The following archives have also been consulted: Arch. des Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes du Canada Francophone (Laval, Québec), Fonds de l’Académie de l’Archevêché, dossier 501571 (book); Library & Arch. of the National Gallery of Can. (Ottawa); BANQ-CAM, TP11, S2, SS2; SS20, SSS48; Canadian Centre for Architecture, Architectural Arch. (Montreal), Fonds Ernest Cormier: project and professional files, 1892–1980; and VM-SA, VM2, rôles d’évaluation.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S51, 29 déc. 1872. Bureau de la Publicité des Droits (Montréal), vol.B-299, no.153624; vol.B-503, no.401134. FD, Sainte-Cunégonde (Montréal), 16 févr. 1907; Saint-Patrice (Rivière-du-Loup, Québec), 4 sept. 1912. Le Devoir, 11 juin 1936. Gazette (Montreal), 12 June 1936. La Patrie, 11 juin 1936. La Presse, 21 mars, 1er oct. 1904; 3 oct. 1905; 17, 25, 29 nov. 1909; 11 juin 1936. Le Soleil, 24 nov. 1922. Académie Commerciale Catholique de Montréal, Palmarès ([Montréal?]), 1888–89. P.‑R. Bisson, “J. O. Marchand: notes biographiques et pré-inventaire de l’œuvre,” ARQ: architecture Québec (Montréal), no.31 (1986): 18–21; “Les rapports entre Ernest Cormier et Jean-Omer Marchand: de l’émulation aux hostilités,” ARQ: architecture Québec, no.53 (1990): 13–16; “Un monument de classe internationale: la maison-mère de la Congrégation Notre-Dame,” ARQ: architecture Québec, no.31: 14–18. John Bland, “Architecture,” in The end of an era: Montreal 1880–1914 (exhibition catalogue, McCord Museum, Montreal, 1977), 11–13. Sharon Irish, “Beaux-arts teamwork in an American architectural office: Cass Gilbert’s entry to the New York custom house competition,” New Mexico Studies in the Fine Arts ([Albuquerque, N.Mex.]), 7 (1982): 10–13. “J. O. Marchand [F.],” Royal Instit. of British Architects, Journal (London), 3rd ser., 43 (1936): 1050–51. P. E. Nobbs, “Architecture in the province of Quebec during the early years of the twentieth century,” Royal Architectural Instit. of Can., Journal (Toronto), 33 (1956): 418–19. Johanne Pérusse, “J.‑O. Marchand, premier architecte canadien diplômé de l’École des beaux-arts de Paris, et sa contribution à l’architecture de Montréal au début du vingtième siècle” (mémoire de m.a., univ. Concordia, Montréal, 1999).

Revisions based on:

J.-F. Pouliot et Gaston Deschênes, “Le ‘Café du Parlement,’” Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée Nationale, Bull. (Québec), 24 (1995), no.1: 22–24. Québec, Assemblée Nationale, “Encyclopédie du parlementarisme québécois”: www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/patrimoine/lexique/index.html (consulted 22 June 2018).

Cite This Article

Jacques Lachapelle, “MARCHAND, JEAN-OMER (baptized Arthur-Omer; John Omer, J. O. Marchand),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marchand_jean_omer_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marchand_jean_omer_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Lachapelle |

| Title of Article: | MARCHAND, JEAN-OMER (baptized Arthur-Omer; John Omer, J. O. Marchand) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |