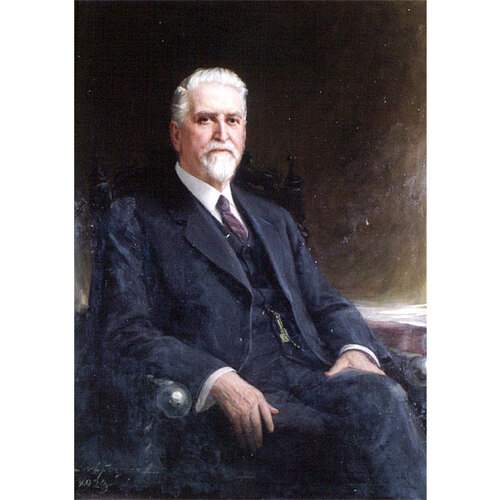

![Robert Mathison, MA [Superintendant and Principal, Ontario School for Deaf, 1879-1906].

John Wycliffe Lowes (J.W.L.)

1923

Oil on canvas

Accession No.: 622616 Original title: Robert Mathison, MA [Superintendant and Principal, Ontario School for Deaf, 1879-1906].

John Wycliffe Lowes (J.W.L.)

1923

Oil on canvas

Accession No.: 622616](/bioimages/w600.12992.jpg)

Source: Link

MATHISON, ROBERT, newspaperman, office holder, educator of the deaf, and administrator of a fraternal order; b. 9 June 1843 in Kingston, Upper Canada, son of George Mathison and Anne Miller; m. before 1863 Isabella Christie (d. 1923) of Hamilton, Upper Canada, and they had two daughters and two sons; d. 30 July 1924 in Toronto.

Of Scottish-Irish parentage, Robert Mathison was educated in Woodstock and Brantford. He worked as a reporter for the Hamilton Times; by 1871 he was co-editor/proprietor of the Brantford Weekly Expositor and secretary-treasurer of the Canadian Press Association. He then moved into provincial positions: bursar of the London Asylum for the Insane in 1872 and manager of industries and bursar at the Central Prison in Toronto in 1878.

In September 1879 Mathison succeeded Dr Wesley Jones Palmer as superintendent of the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb in Belleville. The first in a line of political appointees there, he had no notable acquaintance with educating the deaf. According to the school’s official report of 1880, the government believed that his “varied knowledge and experience of public institution management . . . , combined with his well known administrative ability, eminently fitted him for the position of executive head.” Administered through the office of John Woodburn Langmuir*, provincial inspector of prisons, asylums, and public charities, the institution had been opened in 1870 to “impart a general education as well as instruction in some professional or manual art” to the deaf. When Mathison arrived, according to one obituary, he found it “ill arranged, disorganized and classed with penal institutions and those for the insane.” No attempt had been made to categorize students and no set curriculum existed. One of his first tasks was to have the students graded and courses of study and timetables put into operation.

Mathison was superintendent for 27 years. Whatever his shortcomings in 1879, he became a serious student of educating the deaf and visited similar institutions abroad. A vice-president of the Association of American Instructors for the Deaf, he was joined in his work in Belleville by his daughter Annie, who taught oral articulation. One of his greatest achievements, he believed, was to have the responsibility for his institution shifted in 1905 to the Department of Education, a move urged upon him by the deaf community. The bureaucratic alignment with prisons and asylums had lent a “stigma of inferiority” to the deaf population and led to an association “in the public mind, with the criminal incorrigibles and mentally defective classes.” Other concerns raised by Mathison as superintendent included extending the school term from 7 years to 10 or 12, the costs to parents, and the granting of diplomas. In the debate over the causes of deafness, he disputed the theory of Alexander Graham Bell that deaf parents produced deaf offspring.

Two interrelated issues in particular dominated Mathison’s annual reports: the method of instruction and the purpose of educating the deaf. Mathison had inherited an entrenched system of manual teaching (sign-language with writing) [see Duncan Wendell McDermid*]. He used his reports to explore the potential of both oralism (speech, lip-reading, and writing), the method propounded by the European community, and the combined method (sign-language for instruction, with articulation for those who demonstrated aptitude), the system proposed by moderate American educator Edward Miner Gallaudet. By 1892 Mathison had firmly aligned himself and his institution with the combined system, and was focusing on the development of manners and morals and on industrial training. (The oralists emphasized academic work and intellectual development.) According to Mathison, the primary object of establishing schools for deaf children was “the cultivation of their minds, to teach them the ordinary branches of knowledge taught in the common schools of the country.” The secondary motive was to “have them taught . . . such trades and industries as might prove of advantage to them after leaving school.” The occupations taught (with varying success) included printing, shoemaking, carpentering, baking, and barbering for the boys, and tailoring, dressmaking, sewing, and housekeeping for the girls. In 1897 Mathison was able to note that many former pupils were “well off, others are in comfortable circumstances, few are a burden on their relatives, and none of them are in gaol as prisoners.”

During his tenure Mathison worked actively for the wider deaf community. He supported its efforts in 1886 to organize the Ontario Deaf-Mute Association, of which he was made honorary president, and to form other bodies for the deaf, such as the Brigden Literary, Maple Leaf Reading and Debating, and Dorcas Sewing clubs, most of them in Toronto. In 1893, in recognition of his contributions, the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, in Washington, awarded him an honorary ma.

In November 1906 Mathison left the Ontario Institution. In his last report he noted that he had given himself to his work “with entire devotion” and took great satisfaction from knowing “that I may have aided in some degree in bringing a little more of brightness and joy into the lives of our silent ones.” Why he left when he did is not clear; his departure may have had something to do with two negative evaluations. In 1906 British specialist James Kerr Love visited the institution and found little oral work since Mathison’s purpose was “to make his deaf children earn a living in a country where labor is plentiful and workmen scarce.” A separate government investigation found the system of oral instruction at the school defective and recommended radical changes in its methods. The teaching of articulation was seen to be handicapped, however, not by Mathison’s philosophy but by the failure to give him “the support he deserved” and by too few teachers and insufficient accommodations. His successor, Charles Bernard Coughlin, embraced the oral method, which would be officially adopted by 1912.

After his resignation Mathison moved with his family to Toronto, where he became treasurer and later secretary of the Independent Order of Foresters, which he had joined in 1883. He retired in 1921. A Baptist and a member of the Oddfellows, the National Club, and the Royal Canadian Yacht Club, he passed away in Toronto in 1924 from an apoplectic stroke. Shortly before his death, an oil portrait of him by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster* had been unveiled at the Belleville school by the Ontario Association of the Deaf.

AO, RG 10-20-C-4-1; RG 22-305, no.50452; RG 63-A-10, 836, file 6, J. W. Langmuir to Mathison, 4 Oct. 1879; Mathison to Langmuir, 7 Oct. 1879. Univ. of Western Ont. Arch., J. J. Talman Regional Coll. (London), R. M. Bucke coll., medical superintendent’s journal, vol.3 (1877–84). Globe, 8 Oct. 1923, 13 July 1924. London Advertiser, 15 March 1878. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian who’s who, 1910. C. F. Carbin, Deaf heritage in Canada: a distinctive, diverse, and enduring culture, ed. D. L. Smith (Toronto, 1996). Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, reports of the Ontario Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, Belleville, 1880–1907/8 (the institution’s reports for 1880–81 are found in the reports of the inspector of prisons and public charities). Saturday Night, 27 Aug. 1898. M. A. Winzer, “Education, urbanization and the deaf community: a case study of Toronto, 1870–1900,” in Deaf history unveiled: interpretations from the new scholarship, ed. J. V. Van Cleve (Washington, 1993); “An examination of some selected factors that affected the education and socialization of the deaf of Ontario, 1870–1900” (ed.d. thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1981); The history of special education: from isolation to integration (Washington, 1993).

Cite This Article

Nancy Kiefer, “MATHISON, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mathison_robert_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mathison_robert_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nancy Kiefer |

| Title of Article: | MATHISON, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |