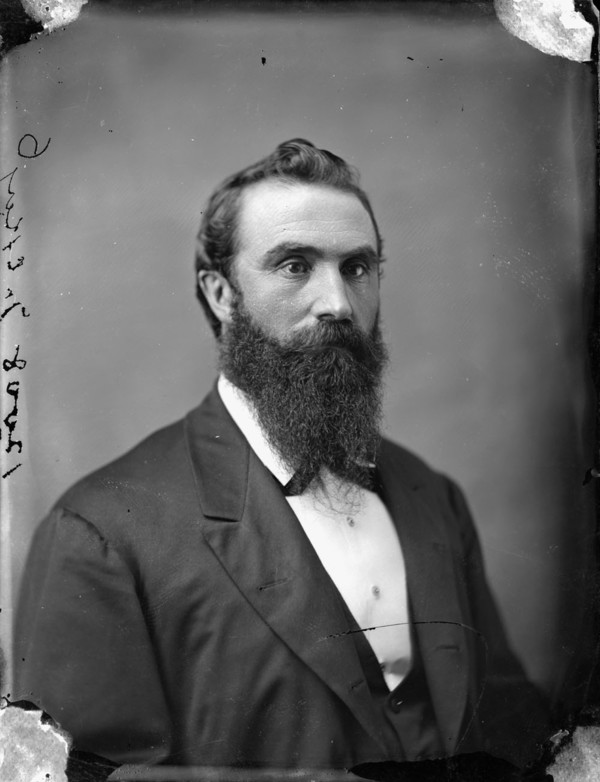

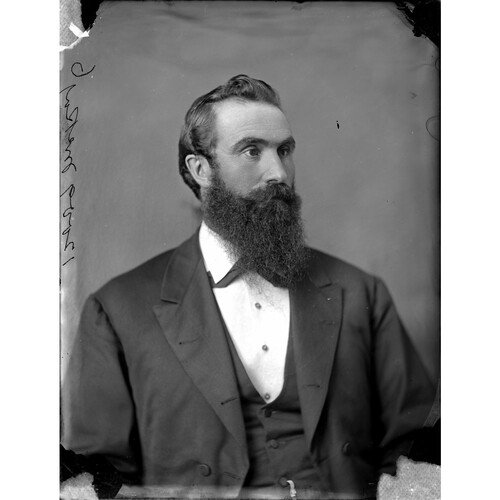

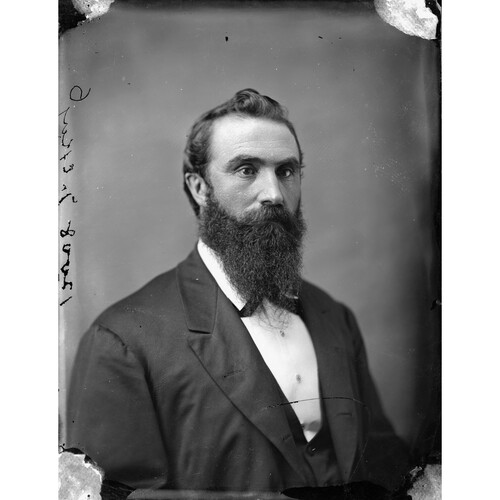

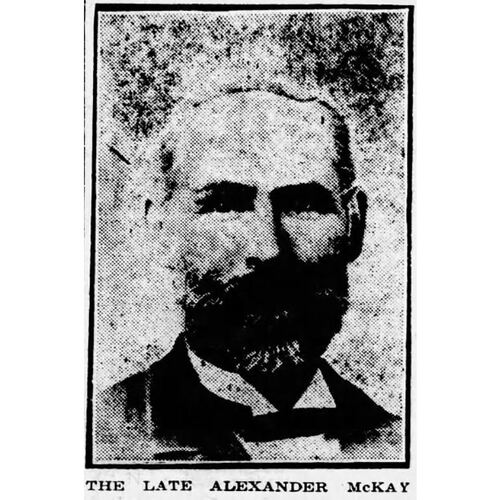

McKAY, ALEXANDER, educator; b. 16 July 1841 in Earltown, N.S., son of Thomas McKay and Mary —; m. 3 Nov. 1871 Caroline Gidney in Sandy Cove, Digby County, N.S., and they had three sons and two daughters; d. 8 April 1917 in Dartmouth, N.S.

Alexander McKay began his teaching career in Pictou County in 1856. In 1859 he graduated from the provincial Normal School, Truro, and then taught in Digby, Colchester, and Kings counties before going to Dartmouth in 1872 as principal of schools. In 1880 he was appointed teacher of mathematics and physical science at the Halifax High School; he resigned in 1883 to become supervisor of Halifax city schools.

Well read in American, British, and German educational theory and practice, McKay was thoroughly conversant with the concepts of the “new education,” which stressed integration of the intellectual development of the child and preparation for entrance into an industrial society. Many of his ideas proceeded from observation of Canadian and American schools and teacher-training facilities. This scrutiny gave rise to his enduring preoccupation with issues such as the proper heating and ventilation of school buildings, the importance of high schools within the public system, manual training and domestic arts, the kindergarten movement, and the need for professionally trained teachers.

McKay concentrated initially on developing a progressive curriculum which, in direct contrast to the classical pedagogy favoured by his predecessor, Benjamin Curren, provided students with practical and technical skills appropriate to the late Victorian era. By 1890 he had introduced instruction in music theory and callisthenics and drill to the classroom. The next year Halifax became the first city in Canada to establish a full manual training program at the secondary school level; this achievement was enhanced in 1903 by the construction of a specialized facility, the Cunard Street Manual Training School, said to be “the best in the Dominion devoted exclusively to that science.” Recognizing the importance of educating pupils for suitable employment in a city heavily dependent upon mercantile interests, McKay also introduced a commercial class at the high-school level, in 1903.

McKay’s ability to cooperate with community interest groups in order to improve the school system was evident as early as 1887, when he began a lifelong association with the new Victoria School of Art and Design as secretary and member of the board of directors. Working closely with Anna Harriette Leonowens [Edwards] and others on the board, he used his position to promote art education for teachers, industrial drawing for pupils, and art appreciation in general throughout city schools.

During the 1890s McKay allied himself with Halifax feminist interests, first to improve the curriculum, and then to promote various social programs within the school system. In 1897 the Local Council of Women agreed to assist the school board financially with a cookery school for girls, an innovation which the supervisor had been advocating since the late 1880s. The project, largely conceived by Edith Jessie Archibald*, encountered immediate difficulties within the Local Council, whereupon McKay persuaded the school commissioners to absorb it into the secondary school curriculum, gleefully reporting in 1899 that “the demand for admission . . . is so great as to be sometimes embarrassing. Even the mothers and sisters of the pupils are . . . desirous of attending.”

In 1906 McKay welcomed the introduction of a school-garden program and the city’s first supervised playground, whereby school-board property was utilized during the summer for the benefit of disadvantaged children. Both initiatives were undertaken by the Local Council of Women and were principally directed by Mary Walcott Ritchie and Margaret Marshall Saunders*. By 1914 McKay was lending his considerable support to the Local Council’s efforts to have female representation on the Halifax Board of School Commissioners.

McKay scored another victory in 1907 through the implementation of a medical and dental inspection service for city schools, the first such program in the Maritimes. It would be followed in 1914 by the appointment of a school nurse. Proceeding from his interest in manual and industrial training and his belief in continuing education was McKay’s collaboration after 1907 with Frederic Henry Sexton in the Halifax Evening Technical School, which was sponsored by the school board and the new Department of Technical Education.

Like many contemporary school administrators, McKay was paternalistic in his relations with teaching staff. His attitude derived from a certain ambiguity in that he was a progressive educator hampered by a school board which consistently lacked sufficient funding for salaries and which moreover encouraged the employment of local talent, chiefly female and untrained. Acutely aware of the need to promote a sense of professional identity among his staff, McKay in 1886 had initiated a resource library and regular teachers’ meetings. In 1895 he helped to establish provincially the Teachers’ Protective Union, and after 1896 he repeatedly called for superannuation pensions, which were finally implemented in Halifax in 1906.

McKay also campaigned vigorously to ensure the provision of formal training for local teachers. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the Summer School of Science, founded in 1887 to provide annual opportunities for teacher training in the natural sciences. He was instrumental as well in obtaining normal school accreditation in 1895 for Mount Saint Vincent Academy, a training facility of the Sisters of Charity; so cordial were his relations with the congregation that its members regarded him as “one of their best friends” in Halifax. From 1893 to 1909 McKay lectured at Dalhousie University, developing an education course which, in its emphasis on practice teaching and school management, provided a local alternative to the Normal School. His para-academic status was ambiguous; when his 50th anniversary in education was commemorated in 1910 it was Acadia University, not Dalhousie, which awarded him an honorary ma.

The supervisor’s efforts were not always successful. His attempt to introduce the half-time system to Halifax schools in 1886 was a dismal failure, and although he managed to begin one kindergarten class in 1891 it was 1915 before the school board agreed to finance an expanded program. His repeated calls for improved instruction in hygiene and temperance produced inconclusive results, as did his efforts to upgrade textbooks and to shift markedly away from the confines of a curriculum long devoted to the classics and the three Rs. His campaign to enforce compulsory attendance was unending, and his calls for a rural “parental school” for truants were politely ignored. By 1914 he was advocating specialized training facilities for immigrant children and the mentally handicapped, but in 1916, in a retrograde move, he followed the actions of Benjamin Curren in calling for a new, segregated school for Halifax blacks.

It was once said of McKay that his “sole object . . . seems to be to improve the public school system of the day”; consequently his personal interests were virtually indistinguishable from his professional ones. He was a member of the Nova Scotian Institute of Natural Science from 1872, serving terms as secretary and president. During the late 1870s he lectured in mathematics at the Technological Institute, part of the short-lived University of Halifax. From the inception of the Halifax Ladies’ College in 1887 to his death, McKay sat on its board of governors. He was a regular contributor to the Educational Review (Saint John); an influential participant in the Provincial Educational Association of Nova Scotia and the Dominion Educational Association; a member of the Temperance Alliance; and in 1902 an appointee to the Acadian commission, which examined how best to teach English in the province’s French districts.

McKay’s emphasis on the practical, his commitment to social activism, his innate sense of diplomacy, and above all his unflagging enthusiasm marked him as an outstanding educator and administrator. He was active during a period of intellectual ferment in educational circles and worked within a tight provincial network where the difference between creators and implementers of ideas is now hard to distinguish; his small but significant contribution to the “new education” has not yet been addressed at length. Overshadowed by Alexander Howard MacKay*, provincial superintendent of education, a colleague and close friend with whom the supervisor is easily confused, and denied the most senior positions in the bureaucracy because he lacked academic credentials, Alexander McKay nevertheless worked quietly, diligently, and effectively to shape Halifax schools into a reflection of the best Canada could offer at the end of the 19th century.

[No personal papers are known to have survived for Alexander McKay. The only published study of his 34 years as supervisor of Halifax city schools is B. A. Wood, “‘Turn the schoolroom into a workshop’: Nova Scotia’s new education initiatives in the language arts, 1888–1910,” Journal of Education (Halifax), 6th ser., 6 (1978–80), no.4: 17–22. While important, this article nevertheless examines only one aspect of McKay’s educational endeavours.

The chief source of published information remains the supervisor’s reports, and to a lesser degree, the chairman’s reports, both contained within Halifax, Board of School Commissioners, Annual report for the years 1880–1916/17. [Mary Power, named] Sister Maura, The Sisters of Charity, Halifax (Toronto, 1956), provides brief insight into McKay’s relations with the local Roman Catholic teaching community, and N.S., Council of Public Instruction, Manual of the public instruction acts and regulations of the Council of Public Instruction of Nova Scotia (Halifax, 1911), reproduces the final report of the Acadian commission of 1902. The Minutes of the annual convention and Report of the convention of the N.S., Provincial Educational Assoc. (Halifax), 1886–95, are useful in assessing the relationship between McKay and the nascent teaching profession in Nova Scotia. Obituary notices for McKay, such as those carried in the Journal of Education, 3rd ser., 9 (1917–19), no.1: 143–44, and the Halifax Evening Mail, 9 April 1917, are important for supplying biographical detail.

Among the manuscript sources found most useful in reconstructing McKay’s extracurricular activities were the records of the Victoria School of Art and Design, Halifax, specifically the minutes of directors’ meetings, 1887–1914 (PANS, MG 17, 44, nos.1–2) and the minutes of annual meetings, 1887–1917 (MG 17, 6, no.2). Also relevant are the minute-books of the Halifax Local Council of Women, 1894–99 (PANS, MG 20, 535, nos.1–2). l.k.y.]

Cite This Article

Lois K. Yorke, “McKAY, ALEXANDER (1841-1917),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckay_alexander_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckay_alexander_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lois K. Yorke |

| Title of Article: | McKAY, ALEXANDER (1841-1917) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |