Source: Link

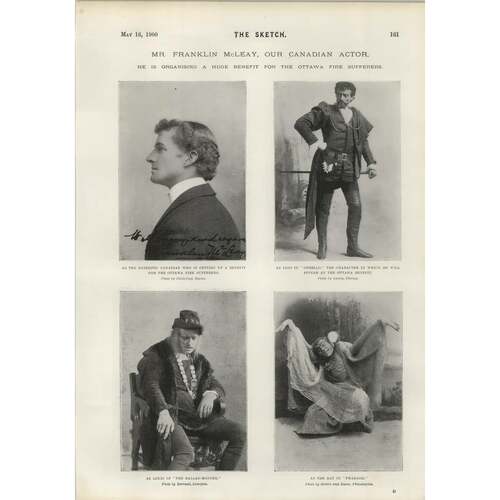

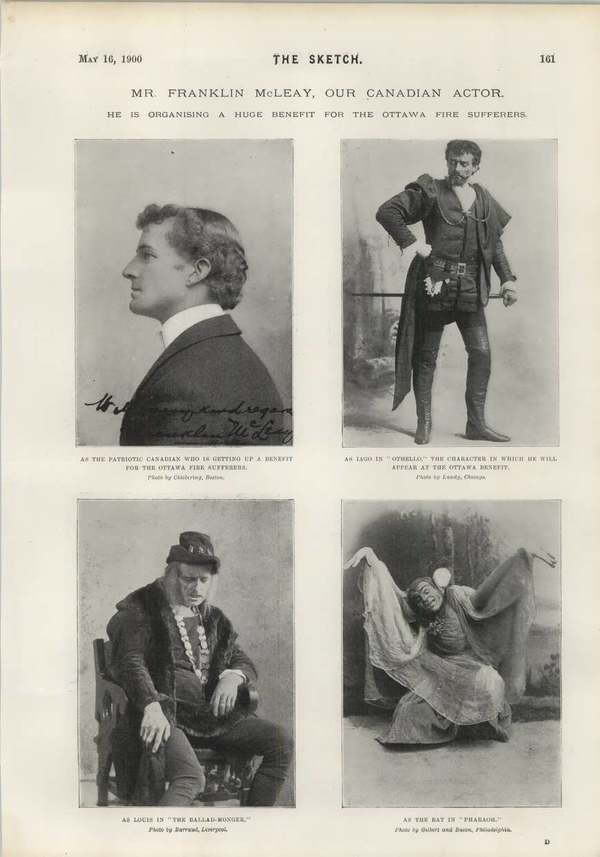

McLEAY, JAMES FRANKLIN (Franklyn), teacher and actor; b. 28 June 1864 in Watford, Upper Canada, son of Murdo McLeay, merchant, and Janet Glendenning; m. 18 Dec. 1898 Grace Warner; d. 6 July 1900 in London, England.

James Franklin McLeay was named after Sir John Franklin*, the Arctic explorer whom his Scottish grandfather, John McLeay, a former Hudson’s Bay Company official, had accompanied on two expeditions. Raised in Watford, Franklin attended the Canadian Literary Institute in Woodstock, from which he graduated with a scholarship in modern languages, and then entered the University of Toronto in the autumn of 1884. Franklin majored in English literature, French, German, and Latin, and he was president of the Modern Languages Club. He also shone in athletics, winning medals as a distance runner and captaining the university’s baseball and football teams.

At university, McLeay said in an interview in Massey’s Magazine in 1896, he was “filled with a great enthusiasm” for Shakespeare and responded to the lectures of David Reid Keys with feelings of “souls acting and re-acting one upon another.” In Toronto he took elocution classes with speech recitalist Jessie Alexander, but there is no record of any involvement in amateur dramatics. In 1888, before graduating, he accepted the post of modern languages master at Woodstock Collegiate Institute. Two years later, while vacationing in Grimsby, he met veteran American actor and teacher James Edward Murdoch and was persuaded to take a lucrative position at his School of Oratory in Boston. McLeay both taught and studied with Murdoch. In 1890, when noted English actor-manager Wilson Barrett was visiting Boston, Murdoch introduced McLeay to him, and Barrett asked him to join his theatre company. McLeay declined but, when the offer was repeated six months later, he accepted. He made his début in Liverpool, England, in 1890, performing a small part in Claudian. Between 1892 and 1895 Barrett and his company toured America, playing Montreal and Toronto frequently, with a repertoire that included Shakespeare and melodrama.

Though not egotistical, the blonde, blue-eyed McLeay was ambitious, and he was blessed with a striking physical presence and a resonant voice. Quickly he graduated from minor to major roles, becoming a master of make-up and an intelligent, versatile, and exciting character player who was noticed for the originality and the emotional shadings of his performances. He achieved fame playing a crippled court fool called the Bat in Pharaoh, a costume spectacle adapted by Barrett. As Hector Willoughby Charlesworth* tells us in Candid chronicles, “Egyptian kings used to deliberately break the bones of children to turn them into grotesques. . . . Only a man who had been an athlete could have stood the physical pain of acting throughout an entire evening in a stooping position. . . . The genius of McLeay was such that he made this grotesque role so dignified and pathetic as to remain forever in the memory of those who saw it.” Among his finest North American performances were the Ghost in Hamlet and, noted the Toronto World in 1895, a “strikingly original” Iago; Charlesworth described the interpretation as that of a “laughing, plausible scoundrel, not the sinister, palpable villain of the old convention.” McLeay created another sensation as the infamous Nero in Barrett’s Roman drama The sign of the cross. It had its première in St Louis, Mo., in 1895 and then was transferred triumphantly to England, opening at the Lyric Theatre in London on 5 Jan. 1896. McLeay’s highly researched performance was the talk of the town, and his playing was compared to that of Sir Henry Irving for its scholarly accuracy and masterly study of insanity. Opposite McLeay as the Empress Poppaea was Grace Warner, daughter of English actor Charles Warner and a beauty “with a wonder of fair hair.” In 1899, the year after their marriage, Saturday Night spoke of the possibility that they might form their own company. When Barrett left in 1898 to tour Australia, McLeay stayed in London to join Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s famous classical company at Her Majesty’s Theatre. Over the next two years he gave memorable portrayals of Cassius in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and Hubert, the gentle executioner, in King John, as well as Cardinal Richelieu in a stage adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s The three musketeers.

Then, suddenly, at the age of 36, McLeay’s short, meteoric career ended. On 26 April 1900, in Canada, fire devastated Ottawa and Hull. McLeay organized a giant benefit to raise money for the thousands of homeless families. Called “The Canadian Matinee,” it began at 12:30 p.m. on Tuesday, 19 June, at the Drury Lane Theatre in London. Queen Victoria was the patron and the Prince of Wales booked a box for the occasion. The matinée lasted about six hours, during which the reigning stars of London’s stage performed a pot-pourri of musical and dramatic selections. Tree essayed a few scenes from Othello for the first time in his career, with McLeay supporting as Iago. They were planning to mount a full-scale production in the autumn, but the preview proved to be the only time London saw McLeay’s Iago. Although an anonymous critic in the Times acknowledged, “How could any one judge their efforts fairly with the refrain of a comic song still ringing through the theatre,” both players were chided for forcing their interpretations. Obviously the tensions and responsibilities of the undertaking were immense. In addition, there were legitimate protests because, by June, the Ottawa fund had been oversubscribed, though McLeay could not have foreseen this when he undertook to organize the performance. A memorandum was inserted into the program stating that “no question of charity was involved. The matinée was intended as an expression of the sympathy of the dramatic profession with their fellow-subjects of the Dominion.” It was left to Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] and Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* to distribute the $15,000 that was raised; the Toronto Globe reported a suggestion that the money go to help famine victims in India. On top of all this the “highly strung” McLeay was playing every night in the weeks preceding the matinée and even on the evening immediately following it. The Times said that “the labours and worries of his task overtaxed his brain.” The Globe noted that he died on 6 July 1900 of “brain fever, after an illness of some weeks.” Charlesworth, writing in 1925, said that he “took a chill, and, already run-down from overwork . . . died of pneumonia within three days.” Altogether McLeay had played more than 40 roles.

On 11 Aug. 1900, at Her Majesty’s Theatre, Tree eulogized the young Canadian with deep feeling. Six days later, in Ontario, the Hamilton Spectator published the size of his estate: £94 17s. 2d. – “not so much for so sincere a worker.” Marvelling in 1925 at the perpetuation of his fame in England, Charlesworth tells us, “Many London actors believe that he would have become known as the greatest actor of the twentieth century.”

NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Warwick, division 4:39–40 (mfm. at AO). UTA, A73-0026/286 (25). Saturday Night (Toronto), 1 April 1899: 7. W. J. Thorold, “Canadian successes on the stage,” Massey’s Magazine (Toronto), 2 (July–December 1896): 189–92. Globe, 20 June, 7 July 1900. Guide-Advocate (Watford, Ont.), 13 July 1900. Times (London), 11, 20 June, 7 July 1900. Toronto World, 20 Feb. 1895, 7 July 1900. H. [W.] Charlesworth, Candid chronicles: leaves from the note book of a Canadian journalist (Toronto, 1925). Franklin Graham, Histrionic Montreal; annals of the Montreal stage with biographical and critical notices of the plays and players of a century (2nd ed., Montreal, 1902; repr. New York and London, 1969). Victor Lauriston, Lambton’s hundred years, 1849–1949 (Sarnia, Ont., 1949), 123. Globe and Mail, 27 Jan. 1982: 16.

Cite This Article

David Gardner, “McLEAY, JAMES FRANKLIN (Franklyn),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcleay_james_franklin_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcleay_james_franklin_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Gardner |

| Title of Article: | McLEAY, JAMES FRANKLIN (Franklyn) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |