Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MIKAK (Micoc, Mykok), Labrador Inuk; b. c. 1740, daughter of Inuk chief Nerkingoak; m. c. 1762 the son of an Inuk chief, m. c. 1770 Tuglavina, m. 1783 Serkoak; mother of at least one son and one daughter; d. 1 Oct. 1795 at Nain, Labrador.

Mikak is one of the first Inuit to emerge as a distinct individual in the history of the relations between the Europeans and the natives in Labrador. In 1765 the Moravian Brethren sent four missionaries on an exploratory expedition to contact the Labrador Inuit. From the British base of Chateau Bay on the Strait of Belle Isle the missionaries visited nearby encampments of Inuit who had come south for summer trade. A sudden September storm forced the missionaries Jens Haven and Christian Larsen Drachart to stay overnight in the tent of a native religious leader or angakok. Mikak was present in the tent, learned the names of the missionaries, and memorized a prayer taught her by Drachart.

Mikak’s next known contact with Europeans occurred under less happy circumstances. In November 1767 an Inuit band attacked Nicholas Darby’s fishing station at Cape Charles, northeast of Chateau Bay, killing some men and taking away boats. A detachment from Fort York at Chateau Bay pursued the Inuit, killing the men and capturing the women and children. Mikak was carried to Chateau Bay with the other prisoners and spent the winter at the blockhouse. Her evident intelligence attracted the attention of the second in command of the garrison, Francis Lucas*. With his help she picked up English quickly and in return taught him some Inuit words. In the autumn of 1768 Hugh Palliser, then governor of Newfoundland, arranged for Mikak, her son Tootac, and an older boy, Karpik, to be taken to England. His intention was to impress them with the power and grandeur of England so that they would advocate cooperation and trade when they returned to their people. Upon arrival in London Mikak again met Jens Haven, and learned that the Moravians were eager to secure a land grant for a mission post on the Labrador coast.

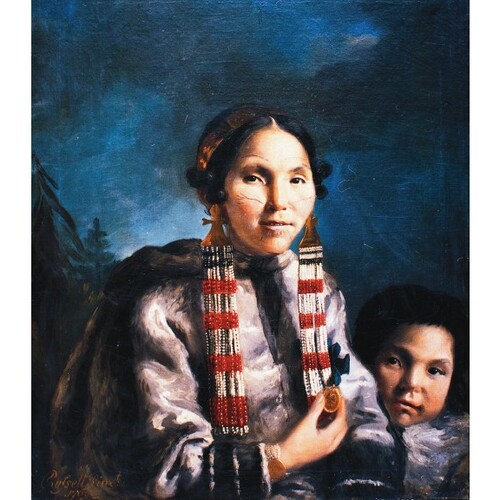

In an age when “noble savages” were in fashion, Mikak was patronized by London society. Among other gifts, she received from Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, a costly dress trimmed with gold lace. At the instance of the naturalist Joseph Banks* Mikak sat to the society painter John Russell. The portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts and now hangs in the Ethnological Institute at Göttingen University (Federal Republic of Germany). Clothed in the dress given her by the dowager princess, Mikak looks out with a shrewd and observant eye. She repeatedly urged the cause of the Moravians before her well-connected patrons, and partly because of her efforts the Moravians received their grant in May 1769. The missionaries, however, disapproved of Inuit being taken to England, feeling that contact with European society spoiled them for the life to which they must return.

In the summer of 1769 Lieutenant Lucas landed Mikak on an island northwest of Byron Bay (north of Hamilton Inlet), and in the following year the Moravians dispatched a ship to look for a likely mission site. In July 1770 the missionaries Drachart and Haven met Mikak and her family near Byron Bay. She received them in her golden gown, with the king’s medal on her breast, and her new husband Tuglavina at her side. As an angakok Tuglavina wielded great influence among his countrymen and came to be both respected and feared by the Moravians for his intelligence, courage, and “turbulent spirit.” The missionaries told Mikak they had come to find a suitable place for a mission, if the Inuit approved, but warned sternly that stealing or murdering would be punished. According to their report, she replied with some spirit that she was “sorry to hear that we had such a bad opinion of their country people” and pointed out that the English also stole, but ended by saying that “they loved us very much and desired that we would come and live with them.” Subsequently Mikak and Tuglavina guided the missionaries northwards and helped them pick a suitable site for Nain, the first mission post.

When the Moravians established Nain in August 1771, Mikak and her family visited but preferred not to live at the station. Mikak and Tuglavina entered a baptismal class but did not proceed further. Indeed from 1782 onward they joined other Inuit in frequent voyages, against the advice of the missionaries, to visit the European traders around Chateau Bay, trading whalebone and furs for guns, ammunition, and liquor. Mikak was attracted to the rough and ready European traders and returned to Nain only at the end of her life in 1795. Then she turned to the missionaries for comfort, saying that she had not forgotten what she had heard about the Saviour or what she had promised when she became a candidate for baptism.

In 1824, a Methodist missionary, Thomas Hickson, met in Hamilton Inlet two Inuit, father and son, each with two wives. The older Eskimo was none other than Tootac. One of his wives wore the golden gown presented to Mikak so many years before, and Tootac himself bore the name of Palliser, after the Newfoundland governor who had befriended them.

Mikak was highly intelligent, observant, and quick to learn. She could be generous and kind, as when she pleaded the cause of the Moravians in London and helped them to settle in Labrador. She seems to have remained her own woman, receptive to the Moravians’ teachings but not without a degree of reserve, enjoying European society but conscious of her influence and place in the Inuit community.

Methodist Missionary Soc. (London), Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Soc. correspondence, T. Hickson’s journal on the Labrador C. (mfm. at United Church Archives (Toronto)). PAC, MG 17, D1, Voyage to Labrador, 1770. PRO, Adm. 51/629; CO 194/16; 194/27; 194/28. “Account of the Esquimaux Mikak,” Periodical accounts relating to the missions of the Church of the United Brethren, established among the heathen (London), II (1798), 170–71. Daniel Benham, Memoirs of James Hutton; comprising the annals of his life, and connection with the United Brethren (London, 1856). Hiller, “Foundation of Moravian mission.” The Moravians in Labrador (Edinburgh, 1833). H. W. Jannasch, “Reunion with Mikak,” Canadian Geographical Journal (Ottawa), LVII (1958), 84–85.

Cite This Article

William H. Whiteley, “MIKAK (Micoc, Mykok),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mikak_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mikak_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | William H. Whiteley |

| Title of Article: | MIKAK (Micoc, Mykok) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |