Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MONK, HENRY WENTWORTH, farmer, social reformer, author, and journalist; b. 6 April 1827 in March Township, Upper Canada, second son of Captain John Benning Monk and Eliza Ann Fitzgerald; d. unmarried 24 Aug. 1896 in Ottawa.

Henry Wentworth Monk was the son of a Roman Catholic mother and a Protestant father; Captain Monk, a native Nova Scotian, had settled in 1819 among other half-pay officers in March Township on the Ottawa River. In 1834 he sent the seven-year-old Henry to an English public school, Christ’s Hospital, in London. Henry was recalled in 1842 to help on the family farm but the distinctive piety of the school had turned him to his lifelong concern with religion. He gained a bursary from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in 1846 to train as an Anglican priest. After a year, however, he left this study, probably at Cobourg under Alexander Neil Bethune*, when he broke permanently with orthodox Christian theology and returned to farming, beginning his own operation at South March. In 1853, inspired by American millenarian enthusiasm for an imminent Jewish return to Palestine, Monk worked his passage to Jaffa (Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel) as a sailor.

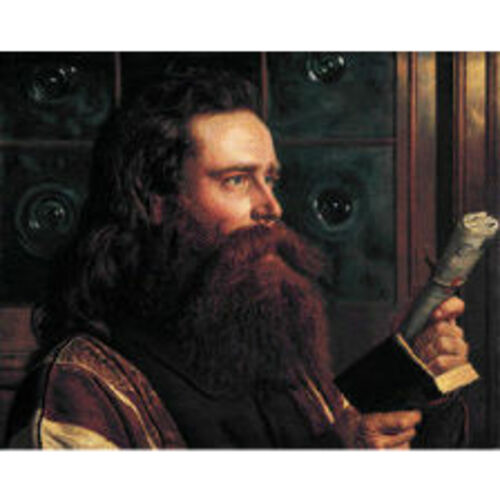

While working near Jerusalem as a farm labourer on the Ourtass colony, one of the first Jewish agricultural colonies in Palestine, Monk met the young Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt. Hunt, who had come to Jerusalem to gain direct experience for religious themes, not only painted Monk’s portrait (as a latter-day prophet) and used him as a model for Christ in sketches but also imbibed at least some of Monk’s religious ideas. According to author Richard Stanton Lambert, the two intended to launch a joint appeal for a new moral order in prophetic painting and writing. Hunt’s The scapegoat can be seen as the counterpart to Monk’s major work, A simple interpretation of the Revelation . . . , a Utopian tract written in two years following his return to Upper Canada in 1855. Late in 1857 Monk journeyed to England to have the book published, a goal achieved in 1859 with funds anonymously supplied by noted art critic John Ruskin.

In this work Monk, commonly described as a Christian Zionist (a millennially minded Protestant who urged the return of the Jews to the Holy Land to facilitate Christ’s second advent), made clear that for him “the restoration of Judah and Israel” meant neither all Jews nor only Jews. Identifying “Judah” as the Jews, and “the ten lost tribes of Israel” as “the European or nominally Christian nations,” he wished only “the best among mankind” to move to Israel. Monk’s sympathy for the Jews did not prevent him from Anglo-American ethnocentricity: in an 1871 pamphlet he would employ a phrenological argument to explain why “the European, or Caucasian, races excel all others.” Undoubtedly part of his appeal to such men as Ruskin and Hunt lay in his belief that the mechanical advances of the 19th century could all be linked to Biblical prophecies. Monk held that railways, steamships, and the telegraph made possible a world government based in Jerusalem whose first act of justice would be the full emancipation of the Jews.

Despite his support, Ruskin nevertheless maintained a critical distance, demanding that Monk prove his prophetic credentials. In 1862 he financed Monk’s return to Upper Canada, setting as a “test” the prophet’s ability to end the American Civil War. Monk proposed a peace based on the North’s allowing the South to secede on condition that the South abolish slavery. In March 1863 he visited a bemused President Abraham Lincoln but he failed to gain access to Confederate territory. After this débâcle, Monk returned to London, and then to Jerusalem where he found the Ourtass colony dispersed. After addressing appeals to wealthy Jewish and Christian leaders, he sought to return to Upper Canada. His ship was wrecked off Massachusetts on 24 March 1864. The sole survivor, Monk underwent great hardship and probably a partial loss of memory. He eventually found his way to Ottawa, where his family nursed him back to full health. A return to farm work restored his vigour but he was given to “various personal eccentricities”: a continuing refusal to cut his hair or beard, a strong fear of contamination by germs, a desire to perform outdoors as many routine functions (such as eating and sleeping) as possible, and a habit of relieving severe pains in his head by “plunging his whole head into ice-cold water.”

Pondering the failure of his prophetic vision, he again turned to Biblical study, attempting to update his vision through scientific experiments and cosmology. In 1868, supported by his own labour, he began touring various American Utopian or millenarian communities. By August 1872 he was again in London, reunited with Hunt, pouring forth grand settlement schemes for Palestine to be funded by governments or business leaders. Monk attempted to spread his new message in Our future . . . , a book to be issued serially. After the appearance of the first segment in December 1872, Ruskin, increasingly impatient with Monk’s lack of prophetic success, withdrew his patronage and the second number was never published. A discouraged Monk once again returned to Ottawa. There he took up journalism. After the Free Press published a number of his letters explaining his ideas, the Ottawa Daily Citizen commissioned him to produce a series of articles on events of the day. By 1875 he had become a notable local figure, and he began to concentrate on the Palestine Restoration Fund, a scheme he had devised to raise money to buy Palestine from Turkey. Buoyed by his growing prestige and by the prospects for success, Monk returned to London in 1880, once more hoping to secure a hearing from the powerful for his millennial vision of Palestinian settlement and world peace. He corresponded freely for a time in the Jewish World and, after failing to influence the wealthy, strove to recast his millennialism in a scientific mold. In January 1883 he published World-life . . . , a short pamphlet reaffirming his cosmological theories. But by 1884 he had again lost his audience and, penniless, he returned to Ottawa.

Until his death he ceaselessly lobbied for his ideas through newspaper articles, pamphlets, and letters to the powerful. Increasingly his emphasis shifted to the creation of an international tribunal to ensure world peace. In March 1889 he gained an interview with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and late that year in the House of Commons Conservative George Moffat gave notice of a motion that would appoint Monk as Canada’s representative to persuade Britain and the United States to support a tribunal. The motion was never introduced. In March 1896, shortly before Monk’s death, Charles Arkoll Boulton moved, unsuccessfully, a resolution in the Senate approving of the creation of an international tribunal. Although he never brought his plans to fruition, Monk had enjoyed influence in various circles, which seems to have arisen from his education as an English gentleman, the force of his personality, and his dedication to a single idea.

R. S. Lambert, For the time is at hand: an account of the prophesies of Henry Wentworth Monk of Ottawa, friend of the Jews, and pioneer of world peace (London, 1947), is the only full study of Monk published and contains an exhaustive list of his publications. Information on Monk is also provided in W. H. Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (2v., London, 1905–6), 1: 432–35, and H. F. Wood, Forgotten Canadians (Toronto, 1963), 112–19.

Cite This Article

Peter A. Russell, “MONK, HENRY WENTWORTH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 17, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/monk_henry_wentworth_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/monk_henry_wentworth_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter A. Russell |

| Title of Article: | MONK, HENRY WENTWORTH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 17, 2026 |