Source: Link

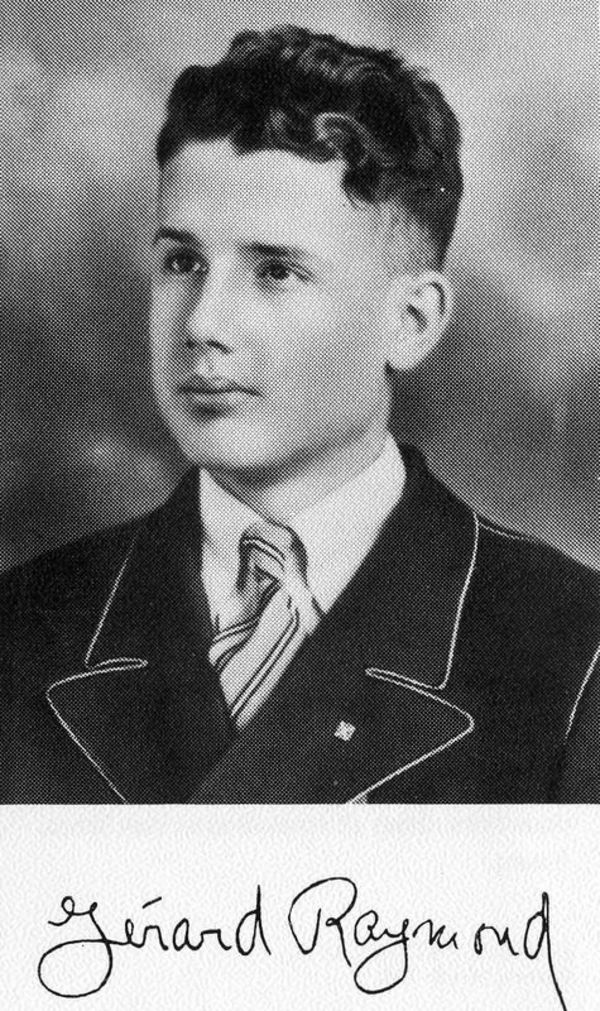

RAYMOND, GÉRARD (baptized Joseph-Louis-Gérard), mystic and author; b. 29 Aug. 1912 in Quebec City, son of Camille Raymond and Joséphine Poitras; d. there 5 July 1932 and was buried 9 July in the Saint-Charles cemetery.

Gérard Raymond was the fourth of eight children born to a family living in Quebec City’s Lower Town. According to his baptismal certificate his father was a shoemaker, but according to the city directories he was a driver. Gérard quickly attracted attention because of his piety and intellectual ability so the clergy in his parish helped him undertake his classical studies. From then on his short life was essentially divided between his home in the parish of Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici (also known as Sainte-Angèle-de-Saint-Malo) and the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he was accepted at the age of 12 and excelled in his studies. Diagnosed with rapidly developing tuberculosis at the beginning of 1932 during his final year of the Philosophy program, he would leave them both for the Hôpital Laval, where he would succumb to the disease.

So who was this Gérard Raymond, whose reputation for saintliness endures? One wonders how he could still be held up as a role model for youth in 1992 in a work entitled Un défi aux jeunes despite the great divide between the French Canadian society of his time and Quebec society at the end of the 20th century. There are other questions: how to explain the success of the book about him written by Oscar Genest shortly after Raymond’s death, and the 1937 publication of his diary with a print run of some 20,000 copies and translations in several languages? What is this odour of sanctity that the pious public steadfastly recognize in him so that the notion of his beatification is regularly revived with ecclesiastical authorities (a canonical proceeding was initiated in October 1956)?

Most of what is known about Raymond is contained in the eight notebooks of his diary written between 23 Dec. 1927 and 2 Jan. 1932 during the last years of his life. They recount his daily efforts to attain his student ideal. “Today I was weak. [I got] up after 6 o’clock …, I did not stick to my rules; no spiritual reading. But I intend to develop my willpower at all costs.” Sustained by a relentless examination of his actual shortcomings, Raymond made them part of a plan for both his academic and his spiritual life. “In my diary,” he wrote on 11 Sept. 1929, “I plot campaigns, I map out programs. So as not to waste too much of my time, I make myself a schedule for each day.”

By recalling his successes, and failures, which in fact were instances of dissatisfaction with himself, Raymond sought resolutely to move forward. “Quo non ascendam?” (Why am I not on the way up?) he kept asking. This haunting fear fed a will to succeed, unceasingly reasserted. This perfectionist program on both the academic and spiritual levels led him to constantly re-evaluate his progress, fret over his faults and relative failures, and strive to find out how to improve. He looked everywhere for ways to outdo himself: in his studies, his worship, and his respect for college and personal rules (such as diligence at prayer and consistency in his efforts). His spiritual search was an integral part of his daily life whether at school, in chapel, or on vacation. The diary recounts both the little mortifications to which he subjected himself and the great hopes of his life. It contains personal reflections as well as summaries of readings and sermons. Raymond assesses his academic performance and his attempts at self-discipline. This ongoing quest to better himself and this rigorous examination of his conscience would earn him a reputation at the college as an “exceptional person.” These efforts were sustained until his final moments, and they would take on the odour of sanctity.

Decidedly modern in his determination to frame the issues of his life, Raymond nevertheless relied on and respected the traditional ways of life and thought of his time, which shaped his spirituality as well as his personality, dreams, and aspirations. Like all students nearing the end of their classical studies, he reflected on his vocation. Of course, he had always known that he would be a priest, but this certainty was nevertheless at the centre of an internal debate. He wrestled with the question of whether to become a secular priest or a member of a missionary order.

The issue was not as insignificant as it may seem nearly a century later. To be a secular priest would guarantee success to this gifted young man who was already attracting attention, but this alternative was too easy for someone who always aspired to more. To be a missionary, more precisely a missionary to China at the outer limits of the propagation of the faith and of civilization, as imagined by his circle, would give him the opportunity to hope for another kind of glory – nothing less than the glory of martyrdom.

The short story Le sourire du martyr, which Raymond signed on 13 Dec. 1931 with the pseudonym J. Mitré, provides the key to his innermost thoughts. He was in hospital, where he had been admitted on 15 Feb. 1932, when he learned in April that his work had won the Parker prize, an award created by Sir Horatio George Gilbert Parker, and open to students at seminaries and colleges affiliated with the Université Laval. The story is about one of the martyred Canadian saints, Gabriel Lalemant*, depicted three centuries ago as he is dreaming about his future. The author’s own soul-searching, attributed to the young Frenchman, is fully revealed.

Gabriel, meditating at the window of his college dormitory on an autumn evening in 1629, wonders whether to develop his talents as a secular priest or as a member of a missionary order. This dilemma is resolved by combining three strands of thought. The first is a petition to a priestly ideal that calls him to serve, but it also represents a royal road to self-realization. The second incorporates the essentially ethnocentric world view of his place and time. The third includes and sublimates the others to arrive at a truly sacrificial spirituality: “Gabriel hears the call of the Huron souls, he leaves his homeland … crosses the ocean … he suffers … he prays … he works.… Twenty years later, [merciless] to their victim, the barbarians tear out his eyes and burn his lips.… The young martyr can still see and smile.… His eyes are gone, his lips are stiff, but God in heaven has given them life for all eternity.” For his part, Raymond decided to become a Franciscan. The model student thus not only adopts the ideals of those around him, but does so in a spirit that soars beyond them. Here, doubtless, is the real key to his enduring reputation.

In his diary, moreover, Gérard Raymond says not a word about the events affecting the lives of working people in Quebec City, including the long strike of the boot and shoe workers, which lasted from May to September 1926 and was marked by violent incidents. And yet, debates about the condition of the working class concerned his own family. There is no examination either of the social thinking of the church in 1931 when the encyclical Quadragesimo anno was published and when he was president of a branch of the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française at his school. One can speculate about the meaning of these omissions. In these silences Raymond probably reveals many things – as he does in outlining his program of perfection – about the development of the social ideal within reach of a young man of superior intelligence in the Catholic framework of his time, an ideal taking shape far from the clamour of the street but not disdaining the most distant borders of Christendom.

The story titled Le sourire du martyr is appended to Gérard Raymond, Journal de Gérard Raymond (Québec, 1937; repr. 1954).

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Saint-Charles (Québec), 9 juill. 1932. FD, Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici (Québec), 29 août 1912. Le Devoir, 20 janv. 1934. [Oscar Genest], Gérard Raymond (1912–1932): une âme d’élite (Québec, 1933). Raymond Lemieux, “Le sourire du martyr: Gérard Raymond (1912–1932),” in Les visages de la foi: figures marquantes du catholicisme québécois, sous la dir. de Gilles Routhier et J.‑P. Warren ([Montréal], 2003), 49–78. Gérard Mercier, Un défi aux jeunes: Gérard Raymond (Saint-Benoît-du-Lac, Québec, 1992).

Cite This Article

Raymond Lemieux, “RAYMOND, GÉRARD (baptized Joseph-Louis-Gérard),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/raymond_gerard_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/raymond_gerard_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Lemieux |

| Title of Article: | RAYMOND, GÉRARD (baptized Joseph-Louis-Gérard) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |