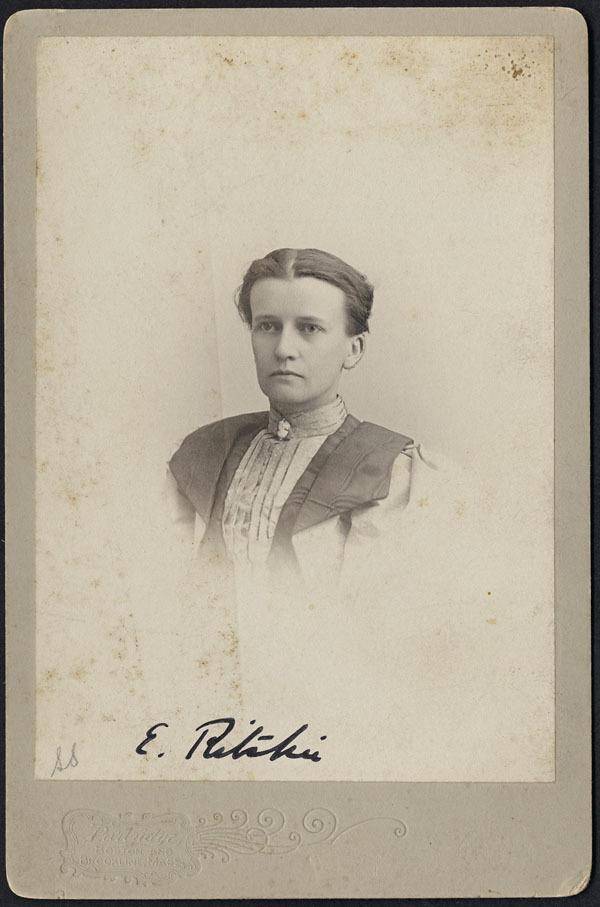

RITCHIE, ELIZA, scholar, educator, author, aesthete, philanthropist, and feminist; b. 20 May 1856 in Halifax, youngest daughter of John William Ritchie* and Amelia Rebecca Almon; d. there unmarried 5 Sept. 1933.

Having had a privileged upbringing and private education, Eliza Ritchie attended Dalhousie University in 1882–83, the year after women were first admitted as undergraduates. She studied for three more years in the “general” (no-degree) category preferred by mature women, along with one, and then two, of her older unmarried sisters, Ella Almon and Mary Walcot. In 1886 Eliza matriculated into the fourth year of the undergraduate course, and the following year she obtained a Bachelor of Letters with first-class honours in philosophy. Attending Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., on a fellowship, she completed a doctorate in 1889 with a major in German philosophy; her thesis was entitled “The problem of personality.” Ritchie was probably the first female graduate of a Canadian university to earn a phd. That year she taught briefly at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and in 1890 she moved to another women’s college, Wellesley in Wellesley, Mass. She remained in the philosophy department there, first as instructor and then as associate professor, for almost a decade; her one absence was in 1892–93 when she went to further her studies in Leipzig, Germany, and Oxford, England. Her employment at Wellesley ended in the autumn of 1899, at a time when some faculty members had found themselves out of favour with President Julia Irvine and the college’s new guard. Although Ritchie may have been dismissed, it is also possible that her departure simply coincided with the purge, especially since she would remain an admirer of the institution.

Ritchie never again engaged in sustained paid employment. Instead, she led a life of “studious leisure” and community activism. For several years she continued with her philosophical research, publishing in the Philosophical Review and the International Journal of Ethics a number of original articles on moral philosophy; her work shows a particular interest in the thought of 17th-century Dutch rationalist Baruch Spinoza. She also regularly produced book reviews on philosophical texts written in Italian, German, and French for the same publications, and she belonged briefly to the American Philosophical Association. By the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, however, Ritchie, supported by a family inheritance, had turned to promoting the appreciation of art and literature and advancing the status of women in her community.

Believing that the Maritimes should be to Canada what she considered New England was to the United States, “a centre for high thinking and for the fostering of art,” Ritchie volunteered her services to Halifax’s Victoria School of Art and Design (renamed the Nova Scotia College of Art in 1925), and in 1917 she joined Ella on its board of directors. In 1908 she was a charter member of the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts, a forerunner of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and she served as vice-president of its governing committee in the late 1920s. She further assisted by making frequent contributions towards the purchase of works for the institution’s collection. In 1906 she became head of the Provincial Exhibition’s art department; during her tenure, which lasted almost continuously until 1917, the displays featured the work of local artists and collections lent by patrons and artists in central Canada, the United States, and England. Among her choice of works were not only paintings and sculptures, but also commercial art; Ritchie, however, drew the line at photographs and examples of “women’s work,” such as weaving, which she relegated to separate spaces. Ritchie worked towards “raising the standard of taste” by giving addresses on the history of European art in Halifax and Saint John; these talks helped secure funds to support art education. Reviewing a speech she gave on Italian masters for the Victoria School of Art and Design in 1905, the Halifax Morning Chronicle described her as “a graceful and fluent speaker, an artist in word-painting, with all an artist’s cultured appreciation of the beautiful. Her lecture, spoken quite without notes, was a masterpiece of composition and eloquence.” Ritchie pressed for the teaching of art in public schools, frequently advocated finding a permanent space for the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts, and chose artworks to adorn Shirreff Hall, the stately women’s residence opened at Dalhousie in 1923 [see Jennie Grahl Hunter Shirreff*]. She often travelled overseas to continue her own education. Indeed, between 1908 and 1930 she spent many of her winters abroad, either in Italy or in England.

Interested in literature, Eliza encouraged contemporary writers and readers. She supported the work of authors such as Archibald McKellar MacMechan, William Bliss Carman*, Lucy Maud Montgomery*, and Charles George Douglas Roberts* by editing the poetry anthology Songs of the Maritimes (Toronto, 1931); the collection included several of her own verses. Eager to disseminate literature, she urged the improvement of libraries for schoolchildren, working people, and college students. Among the deficiencies she identified in the Citizens’ Library of Halifax were the lack of a children’s department, insufficient reading space, and inadequate hours of operation for people who could only visit at lunchtime. She promoted the creation of a library in the house bequeathed to Halifax’s Local Council of Women by Titanic victim George Wright, advocated the provision of libraries in public schools, and contributed to the enhancement of the collections of both Dalhousie University and the art school by making regular donations. To Dalhousie her gifts included not only contemporary works – in 1929, Virginia Woolf’s A room of one’s own, for example – but also valuable 16th- and 17th-century philosophical treatises; the art school’s library was practically established through the generous donation of many lavishly illustrated books given by Eliza and her sister Ella. In 1924, having sent from Italy a book of reproductions of Marc Chagall’s paintings, Ritchie declared, “We must not arrogantly condemn any type of art expression … for curious as modern art may seem to us at the first glance, yet there is oftentimes a big truth endeavoring to find expression by its means.”

Ritchie firmly believed that ignorance bred indifference and that women’s ability to fulfil their potential as citizens depended upon the educational, political, and work opportunities available to them. A liberal humanist, she held that women’s participation in public life should be governed by “intellectual virtues,” especially truth, tolerance, prudence, and moderation. Fearing that radicalism would undermine feminist ambitions, she favoured gradual change. Compared with many of her contemporaries, she was more indulgent in her views on young middle- and working-class women, a democratic approach to feminism that was undoubtedly inspired in part by her experience of living with college women. She was concerned about their opportunities, and worried about the difficulties faced by unenfranchised women competing in the workplace with enfranchised men. At a meeting of the Local Council of Women she argued in 1907 that domestic staff should be treated like employees, not servants; in 1909, during a local council debate over who should control young working women’s leisure hours, she supported self-regulated clubs. In a 1912 lecture on the need to improve teachers’ professional status, Ritchie lamented that teaching was a “stepping stone to something better” for men, but a source of mediocre subsistence for women.

Before and during World War I Ritchie was a leader of the campaign to achieve women’s suffrage. Claiming that suffrage “would make political life purer, would lessen graft and give women a better opportunity in individual life” and that “the spirit of the age is democracy,” she voted with the majority of delegates of the National Council of Women of Canada [see Ishbel Maria Marjoribanks] in favour of enfranchisement at the annual convention in 1910. Around this time she assumed direction of suffrage matters in Halifax’s Local Council of Women, which she had joined while on a visit to her hometown in 1895 (her sisters Ella and Mary were also members), because she chaired the council committee that dealt with citizenship, among other matters. Later, Ella Maud Murray, her successor as convener of the citizenship committee, persuaded historian Catherine Lyle Cleverdon it was Ritchie’s arrogance that had led her to take charge. During the 1917 session of the House of Assembly the local council in Halifax sponsored the drafting of amendments to the Nova Scotia Franchise Act and secured the support of women outside the capital through the activities of the women’s suffrage department of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Ritchie was one of eight suffragists who met with the house’s law amendments committee to present the case for enfranchisement. She also sent direct appeals by letter to women across the province to urge them to use their influence in favour of the legislation. The suffrage bill was given a fatal three-month hoist in April after being treated in the legislature with what she considered unfairness and condescension [see George Henry Murray*]. Revealing the democratic ideals that motivated her, Ritchie wrote in the Halifax Herald of 2 May, “It is not for any little group of ‘intellectuals’ in Halifax and a few other towns that we desire political freedom, we want the great mass of our people, men and women both, [to] be sensible of, and to exercise their responsibility for, the good government of the country.” But by October, as president of the Nova Scotia Equal Suffrage League (also known as the Nova Scotia Equal Franchise League), she was worrying about the indifference of the potential female electorate: “It was time,” she was reported as saying in the Morning Chronicle, “for the women of Nova Scotia to show that they were willing to share with men the burden of citizenship.” Before women’s suffrage in the province finally became a reality on 26 April 1918, Ritchie and her Halifax contemporaries were largely silenced by the enormity of the Halifax explosion of 6 Dec. 1917. During the war years they were also actively working for the reform of municipal politics. The two main issues were women’s exclusion from school boards and the rules disqualifying married women from participating in civic elections. For women active in their communities, the right to vote at the provincial level, while desirable, seemed less relevant than their inability to influence school boards and municipal administration. Ritchie would not live to see women serving on the Halifax School Board.

Ritchie’s activities in her later years focused increasingly on Dalhousie University and the Nova Scotia College of Art. As a member and, in 1911, the president of the Dalhousie Alumnae Association (founded 1909), Ritchie spearheaded the establishment of Forrest Hall, the university’s first, small residence for female students. She helped raise funds by charging admission fees for lectures on art that she gave in 1910 with a fellow art historian, the theologian James William Falconer, and on her own two years later. Ritchie devoted the whole of 1912 to preparations for the residence’s opening, and resigned from most of her other obligations to become unofficial dean of women and to serve as Forrest Hall’s warden from September 1912 until December of the following year. Believing that women’s dormitories should be self-governing, she was lenient with the students. Bessie Hall, one of her charges, commented in 1914 that “dear old Dr. Ritchie knew better than to bring many rules to bear on us.” She was made alumnae representative to the Dalhousie board of governors in 1919, the first woman appointee, and sat for two three-year terms; this was largely an honorary position since power lay with the executive, of which she was not a member. More important was her role as a member of the founding editorial board of the Dalhousie Review, a university quarterly that first appeared in 1921. She also regularly contributed book reviews and notices on works such as Frank Parker Day’s Rockbound (Garden City, N.Y., 1928), and she wrote several biographical and literary articles in which she explored the ideas of truth, beauty, and rationality. She would remain an active editor of the journal for the rest of her life.

In 1927, after figuring prominently in various anniversary celebrations and fund-raising ventures, Ritchie was the first woman to receive an honorary lld from Dalhousie. She also did a little teaching there, taking on a segment of a fine-arts extension course of ten lectures in 1928–29, in collaboration with her long-time associate, J. W. Falconer, and Elizabeth Styring Nutt, the energetic principal of the Nova Scotia College of Art. Ritchie took advantage of her time on the campus to advocate the establishment of a university art museum. For her tireless efforts on behalf of Principal Nutt’s school, she received an honorary diploma in 1931, as did friend and colleague Edith Jessie Archibald. Eliza remembered both the university and the art college with monetary bequests in her will and left her entire collection of some 500 books to Dalhousie.

In An appetite for life: the education of a young diarist, 1924–1927, her younger cousin, diplomat Charles Stewart Almon Ritchie*, confirmed both Eliza’s scholarly preoccupations and her reputation as a freethinker. “She once told me,” he claimed, “that being an atheist ‘was like coming out of a darkened room into the light of day.’” She rejected superstitious and dogmatic thought, writing in the International Journal of Ethics, “If theology is more than superstition, if its arguments are valid, if its objects are verities, it can afford to court the most rigorous examination, and to give praise and cordial welcome to the inquirer who brings to its study the cool impartiality and searching thoroughness of the scientific spirit.” Yet her loyalty to family and community meant that she remained a nominal member of the Church of England.

In her hometown she was known as “the most brilliant of Dalhousie’s girl graduates,” in Dalhousie University circles as “our most distinguished woman graduate,” and in her immediate family as the only sibling who showed signs of the Ritchie “spark of genius.” But in her activities in Halifax, the “superior and aloof” Eliza always shared the limelight with her sisters, the “charming” Ella and the “dynamic” Mary. Their overlapping and complementary interests created confusion about their work and accomplishments in the minds of many contemporaries, including obituarists, and mistaken attributions have been perpetuated by historians. For example, Eliza’s honorary diploma from the Nova Scotia College of Art states that she had been a founding director in 1887, but this distinction belonged to Ella. That Eliza Ritchie was “a woman of inspiring example” was not, however, in doubt.

As part of the celebrations marking 100 years since the graduation of the first woman from Dalhousie University (Halifax) in 1985, the Eliza Ritchie Doctoral Scholarship for Women was established, and it was fittingly awarded for the first time in 1987, the centenary of Eliza Ritchie’s graduation and the 60th anniversary of her honorary degree. In the same year, a small university residence named for her was opened.

Eliza Ritchie’s phd thesis, “The problem of personality,” was published in Ithaca, N.Y., in 1889. A copy is held in the J. J. Stewart Maritime Coll. at DUA, and it is also available in microform (CIHM no.13316). Articles by her appeared in the Philosophical Rev. (Ithaca), including “The ethical implications of determinism,” 2 (1893): 529–43; “The essential in religion,” 10 (1901): 1–11; “Notes on Spinoza’s conception of God,” 11 (1902): 1–15; and “The reality of the finite in Spinoza’s system,” 13 (1904): 16–29. Her articles in the International Journal of Ethics (Chicago) are: “Morality and the belief in the supernatural,” 7 (1897): 180–91; “Truth-seeking in matters of religion,” 11 (1900): 71–82; “Women and the intellectual virtues,” 12 (1901): 69–80; and “The toleration of error,” 14 (1904): 161–71. The Dalhousie Rev. printed the following of Ritchie’s essays: “Goethe restudied,” 1 (1921–22): 160–69; “Marjorie Pickthall: in memoriam,” 2 (1922–23): 157–58; “Contemporary English poets,” 3 (1923–24): 220–28; “Erasmus: a study in character,” 6 (1926–27): 206–17; “William Hazlitt,” 10 (1930–31): 368–75; and “Spinoza,” 12 (1932–33): 333–39. Her work also includes two books, Songs of the Maritimes: an anthology of the poetry of the Maritime provinces of Canada, (Toronto, 1931), which she edited, and In the gloaming … ([Halifax, 1936]), a posthumously published collection of her poems.

DUA, LE 3 D29, 1914/15–33/34; Matriculation book, Dalhousie Univ., 1886/87; MS-2-280, D 212, 213, E 56, 57; UA-1, 1, A-5 to A-8, 1913–33 (minutes); UA-23, boxes 1–3, 1924–34. Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), Estate papers, no.13255. LAC, R2292-0-7, file 7; RG 31, C1, 1881, Halifax, Ward 1a: 124; 1891, Halifax, Ward 1e: 43; 1901, Halifax, Ward 2b-7: 16; 1911, Halifax, Ward 1: 18. NSA, Churches, St Paul’s Anglican (Halifax), RBMB (mfm.); Halifax County Will Books, vol.10, p.548 (mfm. 19361); MG 1, vol.661; MG 17, vols.43, 44, 46; Acc. 1990-392, box 2; MG 20, vol.204, 1908–17; vol.535, nos.1–10, 1894–1933; vol.761, nos.7–8, 1927, no.20, 1933; vol.765, nos.1–2, 1904–14; “Nova Scotia hist. vital statistics,” Halifax County, 1933: www.novascotiagenealogy.com (consulted 15 Dec. 2009). Wellesley College Arch. (Mass.), President’s report, 1891–99. Acadian Recorder (Halifax), 1 March 1895; 2 Nov. 1899; 10 Feb., 1, 3 March 1905; 17 April 1907; 3 Oct. 1908; 18, 21 Sept., 25 Nov., 4 Dec. 1909; 25, 31 Jan., 19 Feb., 6 July 1910; 30 Dec. 1911; 18, 20 Jan., 13, 16, 28 Feb., 1, 2 March, 15, 28 Aug., 4 Sept. 1912; 25 March, 13 Aug. 1915; 6 June, 27 Oct. 1917; 19 Jan. 1929. Dalhousie Gazette (Halifax), 1898–1929. Halifax Daily Star, 7, 8 Sept. 1933. Halifax Herald, 7 June 1887; 12 March, 10 Aug. 1895, woman’s extra; 29 April 1896; 26 Jan., 1 Feb., 12 April, 2 May, 23, 25, 29 June 1917; 6 Sept. 1918; 13 Oct. 1920. Halifax Mail, 31 Dec. 1924, 25 April 1928, 5, 6 Sept. 1933. Morning Chronicle, 20 June 1888, 10 Feb. 1905, 23 Nov. 1911, 27 Oct. 1917, 1 Jan. 1923, 23 May 1928, 2 Nov. 1933. C. L. Cleverdon, The woman suffrage movement in Canada, intro. Ramsay Cook (2nd ed., Toronto, 1974). Dalhousie Alumni Assoc., Alumni News (Halifax), November 1929, January 1938. Dalhousie College and Univ., Calendar (Halifax), 1883/84–87/88 (copies at DUA). Directory, Halifax, 1904–33. W. C. Eells, “Earned doctorates for women in the nineteenth century,” AAUP Bull. (Washington), 42 (1956): 644–51. Judith Fingard, “College, career, and community: Dalhousie coeds, 1881–1921,” in Youth, university, and Canadian society: essays in the social history of higher education, ed. Paul Axelrod and J. G. Reid (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1989), 26–50; “The Ritchie sisters and social improvement in early twentieth century Halifax,” Royal N.S. Hist. Soc., Journal (Halifax), 13 (2010): 1–22. E. R. Forbes, Challenging the regional stereotype: essays on the 20th century Maritimes (Fredericton, 1989). N.S., House of Assembly, Journal and proc., 1906–19, app.5. P. A. Palmieri, In Adamless Eden: the community of women faculty at Wellesley (New Haven, Conn., and London, 1995). Charles Ritchie, An appetite for life: the education of a young diarist, 1924–1927 (Toronto, 1977). R. L. Shaw, Proud heritage: a history of the National Council of Women of Canada (Toronto, 1957). Charles St C. Stayner, “John William Ritchie: one of the Fathers of Confederation,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll. (Halifax), 36 (1968): 182–277. Types of Canadian women …, ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903), 284. P. B. Waite, The lives of Dalhousie University (2v., Montreal and Kingston, 1994–98), 1.

Cite This Article

Judith Fingard, “RITCHIE, ELIZA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 23, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_eliza_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_eliza_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Judith Fingard |

| Title of Article: | RITCHIE, ELIZA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | February 23, 2026 |